17

The Merriams Triumphant

“Worcester! Worcester!

All Change for Webster!”

Goodrich’s health was failing. His wife, Julia, never stopped pleading with him to give up lexicography. His spirits were depressed. “I sincerely wish I could find someone who could take my place,” he told the Merriams in January 1860. “It involves so much care, that is increasing, and such constant liability to driving work in all my working hours, so much setting aside of my appropriate studies that I should not for an instant be tempted to think of it could I think of anyone who would command the confidence of the parties.”1 He could think of one: he was still getting the distinct feeling that the Merriams preferred to have the younger Noah Porter as chief editor.

As Porter had already shown himself to be fully sympathetic to Goodrich’s ongoing efforts to improve Webster’s dictionary, the Merriams concluded that with his Yale connection he would be the logical successor to Goodrich. Just days after receiving Goodrich’s letter in January, they asked Porter to assume editorial control of the dictionaries, perhaps initially as coeditor. But for personal reasons Porter, too, was apprehensive about slipping into the Merriam harness. He was fond more than ever of hiking in the Adirondacks and preferred teaching philosophy, rhetoric, and philology at Yale to drudging through the endless labyrinths of lexicography. The Merriams pressed him to accept their offer, however, and at last he agreed. With that, Goodrich finally had shaken off the lexicographical albatross that had clung to his neck for over thirty years.

As a condition to accepting the job, Porter told the Merriams on February 3, 1860, that there had to be a clear understanding with Goodrich: “I have no wish that Mr. Goodrich should not exercise his judgment and his research and his experience to bring all the original contributions to the work which he can. But if you hold me responsible I must ask that he give me information of all material alterations and suggestions before they go into the copy. . . . Mr. Goodrich as the representative of the family and as one trained under his father’s [i.e., Webster’s] eye and familiar with his principles will of course be expected to give his views at all times—with entire freedom and I shall be very slow to oppose his fixed opinions, but as the cases are numerous and decisions must be promptly made, he must see the necessity of a final decision without long debate.” Having himself successfully and firmly shut the door against his brother-in-law Fowler’s wasteful editorial meddling back in the 1840s, Goodrich understood Porter’s concern, although surely he objected to the notion that he was “trained” by Webster. His role from now on would be strictly advisory.2

Goodrich already had enlisted his colleagues Professors William Dwight Whitney (professor of Sanskrit at Yale and later editor of the rival Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia (1889–91) and Daniel C. Gilman (later the first president of Johns Hopkins University, where he established the first program of advanced graduate education in America) to assume joint control of revising all the nontechnical definitions. Webster’s definitions had been particularly on Goodrich’s mind. Many of them would have to be overhauled or completely rewritten because after Worcester’s edition it was obvious they could not compete. He stressed to the Merriams on January 26, 1860, that in order to bring them into line with C.A.F. Mahn’s new etymologies, they would require a new arrangement: “New senses have come into use, and must be brought in, and to do this in the right way and place requires re-arrangements to a greater or less extent. Sometimes definitions or parts of them are clumsy, unscholarlike, and have been much found fault with—and these must undergo modification. In [the vocabulary] of science, many changes [to the definitions] are requisite, for accuracy, for introduction of later facts, and for conciseness. . . . [A] certain amount of reconstruction is requisite.”3

None of that would ever again be Goodrich’s concern. After a long and heroic career of unending revisions that repeatedly rescued Webster’s dictionaries from the ignominy of lexicographical and commercial failure, he died in New Haven on February 25, 1860. Suffering from migraines for most of his Yale career, he possessed a nervous energy that made him capable of an immense amount of work but which was often physically debilitating. He was buried in Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, and his memorial stone reads, “Professor of the Pastoral Charge Yale College, died Feb. 25, 1860, aged 70.”

In a brief testimony to Goodrich’s religious presence at Yale for more than forty years, the college secretary, Franklin B. Dexter, noted in 1861 that Goodrich provided “unquestionably the most efficient religious influence in the College.” And in his lengthy memorial address for Goodrich at Center Church, New Haven, Theodore Dwight Woolsey, president of Yale between 1846 and 1871, remarked that people often had come from outside Yale to seek Goodrich’s pastoral help: “Probably no man in New Haven was more resorted to as a counselor than he was in the last twenty or twenty-five years of his life.” There is no mention on his monument in Grove Street Cemetery of his academic career or his historically important lexicographical achievements.4

2

Porter now was in charge of overseeing the editorial work for the edition, with William Webster as a token presence to keep the Webster family happy and informed. Porter had already provided some ancillary help with this edition. It was he who, while on a year’s sabbatical in Germany, had looked in on Mahn and, with Goodrich’s approval, hired him to eliminate Webster’s etymology. Now, with Porter’s agreement and advice, the Merriams set about assembling their large team of editors and assistants. They hired William Wheeler, a writer and editor with special expertise in orthoepy; he had assisted Worcester for four years in the treatment of pronunciation and now snatched the opportunity to work for the Merriams. He did not distinguish himself for modesty. “The assistance I furnished [to Worcester],” Wheeler wrote in his job application letter to the Merriams on November 29, 1860, “extended to every department of the work, except synonyms. I think I may justly, and I hope without vanity, lay claim to a considerable share of the merits” of Worcester’s 1860 unabridged quarto. “I certainly am not responsible for many of its defects,” he added vaguely and ungraciously. They hired him annually to import and modify Worcester’s system of pronunciation and spare Porter from some of the general editorial labor.5

In a letter to Wheeler on February 20, 1862, two years after the publication of Worcester’s book, the Merriams reviewed the progress they had made thus far and listed something like thirty professors, scientists, and general assistants who now made up their team. Whitney and Gilman had under their control “the general literary reconstructing and recasting of the definitions. . . . It involves throwing two or more definitions into one, where desirable, giving the definitions in a better, or historical, order . . . correcting, giving literary finish, adopting illustrative citations etc.” Pronunciations were being completely reviewed and given a new set of diacritical notations. Of the thirty researchers at work, remarkably, about half of Yale’s twenty faculty members were among them, several recruited first by Goodrich and the rest later by Porter, in effect making the projected dictionary very much a Yale product. In addition to Whitney and Gilman, who were focusing on definitions pertaining to the arts and literature, other experts were revising the vocabulary of the natural and applied sciences, engineering, the military, legal professions, mathematics, medicine, astronomy, and archaeology. Classical, scriptural, geographical, and biographical tables were being completed; and the collection and engraving of illustrations were well in hand—“we shall make this department pretty full.” “Don’t you think we have a pretty good team?” the Merriams asked Wheeler.6

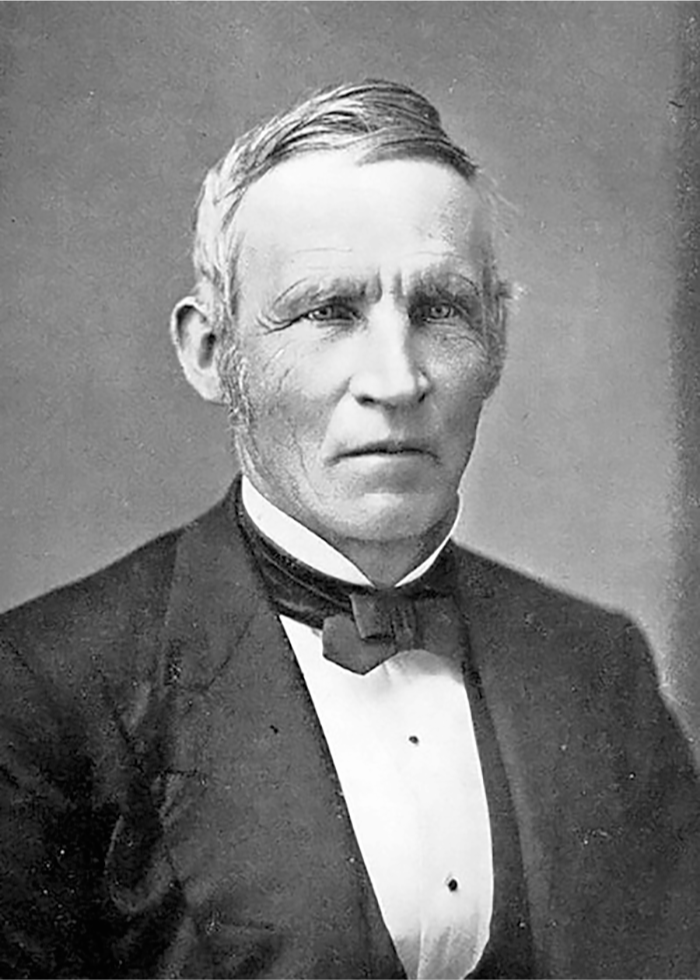

FIGURE 19. Noah Porter, professor of moral philosophy and metaphysics at Yale University, succeeded Chauncey Allen Goodrich in 1860 as editor of Webster’s dictionaries and was the principal editor for the triumphant 1864 edition. Courtesy of Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography, ed. James Grant Wilson, 1888.

When one of the Yale researchers, the eminent geologist and zoologist James Dwight Dana, had to retire from the project because of illness, Porter recruited a young medical student at Yale to take his place. His name was William Chester Minor, featured in Simon Winchester’s best seller The Professor and the Madman (1998), who later, as a convicted murderer, would take up a major, tireless, and sensational role as contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary while an inmate of a psychiatric hospital in England.7 Goodrich’s son, another Chauncey, was also among the assistants, as were a number of literary men who helped with the writing. The Merriams even enlisted the services of George Perkins Marsh, Worcester’s staunch advocate. “We have a long written statement,” Charles Merriam wrote to Wheeler, “for which we paid, from Hon. George P. Marsh, of his views of what a Dictionary should be, and the points of improvement.” One point was a strong urging of “reading the old writers, for obsolescent words—now returning to use, as he [Marsh] thinks—verified by citations. . . . Prof. Porter has also employed several readers with like objectives.”

Courageously and ambitiously, then, while the Civil War was convulsing the nation, throwing the economy into disarray with financial panic and widespread bankruptcies damaging the book trade, the Merriams were spending a lot of money with little certainty of ultimate success in a chaotic market. They were also losing money dramatically, as Charles Merriam recollected about twenty years later: “When the civil war of 1860 broke out, it seriously affected the Book trade. The sales of the speller, fell off greatly. In 1859, the sales were 1,104,948. In 1860, 958,108. But in 1862 they fell off to 308,147. Now the Dictionaries also fell largely off.” George Merriam was determined to forge head, however, whatever was in his way. Paper and bookbinding, for example, right away became expensive for the publication of books, but he made sure enough paper was available to prevent the interruption of the printing of the dictionary. He and his brother had set in motion an expensive and well-tuned engine of laborers and could not afford to wait for economic conditions to improve. Usually three pages of prepared copy were daily given to the compositor, with the proofreading just managing to keep up. The Boston Stereotype Foundry, a typesetting company that since 1859 had been producing the high-quality electroplates from which the edition was to be printed by Henry Houghton in Boston (the founder of what eventually became the publishing firm Houghton, Mifflin and Company) complained to the Merriams that it was losing money waiting for copy that was not being sent promptly and regularly enough to keep up with the established schedule. The root of the problem was annoying delays in the work of several of the scholars, especially regarding the tables. The engraved illustrations were slow coming in as well. Moreover, the foundry was dismayed by the “shocking” quality of the proofs it was receiving, “full as bad as Worcester,” was the complaint (Boston Stereotype had provided plates for Worcester’s 1860 edition). Nonetheless, by May 1864, Houghton was about to begin printing, and by August he was binding about two hundred copies per day. The great dictionary was on target for release before the end of the year.8

Virtually every one of the editors and contributors worked with a copy of Worcester’s celebrated quarto open on his desk. (During the long period when James Murray was editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, called originally the New English Dictionary, he had all his team keep an open copy on their desks of the edition the Merriams were now preparing.) Wheeler’s letters are filled with references to Worcester and how the editorial team was harvesting his work and using him as a standard and benchmark. In light of the Merriams’ hostility toward Worcester and his dictionaries and their carefully orchestrated campaigns against him over a period of twenty years, their reliance on him at this stage has to be regarded as one of the greater ironies in the history of lexicography—not merely that they had Worcester’s dictionary on their desks, but also that they used his work to such an extent, although Webster and they had persistently accused Worcester of doing exactly that to them.

3

An American Dictionary of the English Language, Royal Quarto Edition (10 by 12.5 inches, noticeably larger than a regular quarto) appeared in late September 1864. It contained a massive 114,000 entry words, about 35,000 more than Webster’s original 1828 edition. Mahn’s etymology incorporated the latest Continental philological research. The editors had made every effort to make the pronunciation and spelling (on the back of Worcester) still more respectable and reliable. Diacritic symbols were simplified beyond even what Worcester had done in order to guide the reader toward, especially, current and widely practiced American pronunciation. The definitions were modernized, sharpened, and purged of remnants of Websterian elaboration. In spite of Goodrich and the Merriams’ denigration of Worcester’s synonymy, this edition kept to Worcester’s model of offering numbers of synonyms for each word and the careful discrimination of their meaning. Synonymy took up a good deal of space, but on this matter they were determined not to be outdone by their great rival.

The Merriams and all the contributors knew that the success of the new edition was due in no small measure to the efficient way they took advantage of Worcester’s work. “Thank God for Worcester,” indeed. While not specifying just how extensive the debt to Worcester was, Porter does acknowledge his influence, grouping his dictionary with a clutch of others: “As this Dictionary was designed to be not merely a compilation, but a digest of results obtained by independent research, comparatively few references are made to other Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. But the best works of this kind have been freely consulted, and, among them, the well-known dictionary of Dr. Joseph E. Worcester, which is so honorable to the industry of the author and the scholarship of the country.”9

In his preface, Porter provides some additional perspective on the history and scope of the new quarto. He wants to make sure the reader understands that Noah Webster’s lexicography is scarcely to be seen in this edition except mostly in some lingering definitions. “The work of revising the definitions of the principal words,” Porter writes, “occasioned great and perplexing difficulties to Professor Goodrich and those with whom he conferred.” Even Webster’s introductions to his several editions were eliminated, according to “the wants of the present generation.” Along with all other post-Johnson lexicographers of the language, Porter candidly says that Webster had been trapped by the influence of Johnson’s definitions in spite of his protestations against them: “[H]e had not emancipated himself entirely from the influence of Johnson’s example in accumulating definitions that are really the same, though at first sight they may appear to be different.” Webster’s “theory . . . was better than his practice.” As for the orthography, “to remove every reasonable ground of complaint against the Dictionary . . . an alternative orthography is now given in almost every case, the old style of spelling being subjoined to the reformed or new.”10

4

This new, large, unabridged quarto effectually ended the American dictionary wars of the first half of the nineteenth century. The conductors on trains from Boston to outlying towns were wont to shout out as they pulled into the town of Worcester, “Worcester! Worcester! All change for Webster!” unaware perhaps of a larger meaning of their cries.11

Critical opinion in the United States changed almost overnight. Leading authors who had long preferred Worcester acknowledged the superior fruits of the research of Porter’s team, especially the important etymological contribution of Mahn. Although Holmes remained faithful to Worcester, even he spoke well of the new quarto and admitted he made use of it. Ralph Waldo Emerson assured the Merriams in August, “On my return home from the seashore a few days ago, I found the stately gift you had sent me to my great delight. In my youth my father gave me Johnson’s Dictionary; long after in Cambridge I became acquainted with Mr. Worcester, and bought his book. In the meantime, I have learned from good judges the superiority of Webster’s Dictionary, and am very grateful to you for the gift.” When Long-fellow received a new issue of the Merriam quarto in 1878, and was asked for an endorsement, he struggled against an allegiance to the memory of his old neighbor, realizing that the Merriams had won the war at last: “I have a copy of a previous edition of this valuable work, but the one you now send me seems in many respects more complete.” Although Longfellow still declined to let Merriam use his name and any remarks he might make about the dictionary as part of their advertising, many others did not. John Greenleaf Whittier extolled the dictionary’s “great literary excellence, the unmistakable clearness of its definitions, and the thoroughness and accuracy of its etymology. I have learned to trust implicitly its authority.”12

Even Mark Twain, who had amused himself over the size and weight of Goodrich’s hefty 1847 quarto, added his testimonial. In a letter of appreciation in March 1891 for the gift of a new (third) issue fresh off the press, he was uncharacteristically effusive: “A Dictionary is the most awe-inspiring of all books, it knows so much: and to me this one is the most awe-inspiring of all dictionaries because it exhausts knowledge, apparently. It has gone around like a sun, and spied out everything and lit it up. This is a wonderful book—the most wonderful that I know of, when I think over the impressive fact that if it had been builded by one man instead of a hundred he would have had to begin it a thousand years ago in order to have it ready for publication today.” Twain does not in this passage point out that the large team who produced this marvelous dictionary had made it into something quite different from what Webster wrote. He also may not have been thinking of it at the time, but with that remark Twain does remind us that Worcester and Webster, as well as Johnson, Richardson, Bailey, and a host of lexicographical ghosts reaching back to the seventeenth century and further, did produce their dictionaries practically single-handedly.13

FIGURE 20. The American dictionary wars effectively ended with the publication of the 1864 unabridged Webster’s dictionary, a page of which is shown here. Detail: The definition of apathy includes notations on pronunciation and etymology, an illustrative quotation, a note on its usage in an early Christian context, and several synonyms. Courtesy of Indiana State University Special Collections, Cordell Collection of Dictionaries.

Walt Whitman can have the last word among America’s distinguished authors. He had mixed feelings. In his notes on the American language collected into An American Primer, he expresses his reverence for the language: “America owes immeasurable respect and love to the past, and to many ancestries, for many inheritances—but of all that America has received from the past, from the mothers and fathers of laws, arts, letters, etc., by far the greatest inheritance is the English Language—so long in growing—so fitted.” He had kept close track of the dictionary controversies, though, and there he felt America still did not have “a Perfect English Dictionary”: “Dr. Johnson did well; Sheridan, Walker, Perry, Ash, Bailey, Kenrick, Smart, and the rest, all assisted.” Webster and Worcester “have done well”; “and yet the Dictionary, rising stately and complete, out of a full appreciation of the philosophy of language, and the unspeakable grandeur of the English dialect, has still to be made—and to be made by some coming American worthy of the sublime work. The English language seems curiously to have flowed through the ages, especially toward America. . . .”14

5

In their advertisements, the Merriams heaped endorsements upon endorsements from school and university administrators, government officials, law courts, libraries, and institutions of all kinds across the country, repeatedly publishing them for the next thirteen years, while they remained the “Webster” publishers, in one form or another. They took no chances that at the eleventh hour a Worcester revival launched by J. B. Lippincott, the “largest book jobbers in the United States,” might yet defeat them. Still looking over their shoulders at Worcester, as they had done for more than twenty years, they saturated the country with promotions, publicity pamphlets, and slogans such as “an old sun rising with new splendor,” “get the best,” “a national standard,” “the highest authority in Great Britain, as well as in the United States,” “the only complete English dictionary,” and “like the Egyptian monuments, destined to stand for ages.” They continued to publish innumerable little booklets containing copious reports of sales figures from cities all over the country, with comparisons supporting their contention that Worcester was getting clobbered on all fronts. Even President Ulysses Grant confirmed the Merriams’ claim that their dictionary was the “national standard” in both America and Britain by declaring in a letter to them that this was now “the best Dictionary of the English language ever published at any time in any country.” They correctly claimed it was the largest-selling, single-volume dictionary on the market.15

FIGURE 21. In this Merriam advertisement, Webster’s dictionaries, “like the Egyptian monuments,” are “destined to stand for ages.” Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, G. and C. Merriam Company Papers.

The New York Tribune announced in 1870, only six years after publication, that the Merriam unabridged was becoming something of a national treasure: “The Unabridged is generally regarded as the Dictionary of the highest authority in the language, and has a sale all over the civilized world. It is regularly issued in London, and in English as well as American Courts of Justice is considered as the leading authority on the meaning of words.” The Merriams were particularly keen to demonstrate that their book was international in scope, the standard English dictionary globally. The English publishing firm George Bell & Sons helped them achieve this by acquiring British distribution rights in the 1850s and publishing editions in Britain through the late nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. In their 1886 edition, interestingly, they did away with the word “American” in the title, preferring, Webster’s Complete Dictionary of the English Language. They appeared to think that “American” would be more likely to lose than gain sales in England. They continued to leave off “American” in their later English editions. The American spelling in their editions would not have disturbed English readers as much as the obtrusive word “American” title because by then they were used to it in the lexicon of Worcester and Webster’s dictionaries.

The Merriams’ claim that since the Goodrich-Merriam edition in 1847 they had dominated the British dictionary market seemed at last beyond doubt. The claim was strengthened by an eighteen-page article in the London Quarterly Review for October 1873, “English Dictionaries,” by the Englishman Edward Burnett Tylor, regarded by many as the founder of cultural anthropology. The article was the latest attempt at a history of English lexicography in a country that had come to feel awkward, even ashamed, over how American dictionaries had effectively replaced homegrown ones, except for Walker, who “scrupulously followed Johnson.” Not mentioning Worcester at all, Tylor states the case with a sensible directness that would have further exasperated the English philological world in general and in particular the London Philological Society, which had recently begun work on what became known as the Oxford English Dictionary:

Seventy years passed before Johnson was followed by Webster, an American writer, who faced the task of the English Dictionary with a full appreciation of its requirements, leading to better practical results. . . . Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language . . . appeared at once in England, where successive re-editing has as yet kept it in the highest place as a practical dictionary. . . .

The good average business-like character of Webster’s Dictionary, both in style and matter, made it as distinctly suited as Johnson’s was distinctly unsuited to be expanded and re-edited by other hands. Professor Goodrich’s edition of 1847 is not much more than enlarged and amended, but other revisions since have so much novelty of plan as to be described as distinct works. . . . The American revised Webster’s Dictionary of 1864, published in America and England, is of an altogether higher order. . . . On the whole . . . as it stands [it] is the most respectable, and CERTAINLY THE BEST PRACTICAL ENGLISH DICTIONARY EXTANT.16

If “average business-like character” was the reputation of Webster’s legacy in England, it was a price the Merriams were happy to pay for such praise. They described this article as “an intelligent and most impartial source” and plugged it into several of their advertisements.

6

George and Charles Merriam’s entrepreneurial drive had been commercially successful beyond their dreams. Their sometimes ruthless determination had triumphed. Irked by distractions, they had not tolerated delay—as George Merriam once remarked back in 1844, when he and his brother were struggling to get started with their publishing of Webster’s dictionary, “Don’t let anxieties for progress trouble you, a business man’s fidgets are not always wise. . . . We cannot & will not at this stage resort to delay.”17 It was he who boldly had decided to push on with their final major edition even though the start of the Civil War had complicated the economics of publishing. He and Charles complemented each other well. George was the strategist. Charles was more the diplomat with a literary bent. While George held the title of president of the firm, Charles’s job had always been to correspond with members of the Webster family, several of the dictionary’s editors (mostly Goodrich), and newspaper and magazine editors, forging solutions to the many awkward and potentially damaging complications of family, editors, legal issues, publicity, and the ever-present competition from Worcester.

After thirty-three years on the firing line, in 1877 Charles Merriam sold his interest in the company to the publishers Ivison, Blakeman, Taylor & Company. He died ten years later at the age of eighty-one. George Merriam died in 1880, at age seventy-seven. Their younger brother, Homer, who had taken over as president in 1880 on the death of George, held that post until he was ninety-one in 1904. That ended sixty years of the Merriam family’s control of the Webster lexicons, during which—chiefly with Goodrich’s help—they took Webster’s almost defunct dictionary to world-class fame.

FIGURE 22. Charles Merriam, ca. 1870s. He and his brother George purchased the rights to Webster’s dictionaries in 1844 and, with great determination and skill, made a fortune from them. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, G. and C. Merriam Company Papers.