Chapter 8

Embodiment

The body is incapable of not practicing. And what we practice we become.

Even as you sit here reading … you are shaping yourself by your posture, the way you’re breathing, what you’re thinking, feeling and sensing.

While this may seem subtle and far below the level of our awareness, over time this has a powerful effect on how we perceive the world and how the world perceives us.

—Richard Strozzi-Heckler (2014)

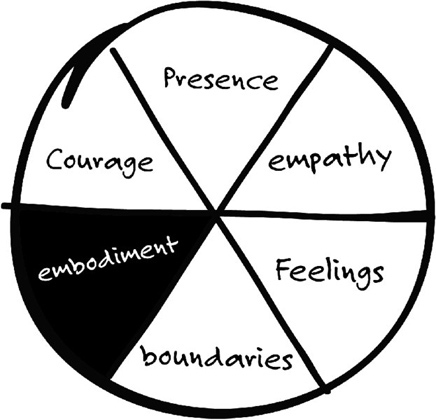

Every action we take originates in our body. Our thoughts, our words, our actions—we cannot produce an action without involving our body. It follows, then, that in order to change we need to engage our body. As Wendy Palmer (2013) so aptly writes, “The way we sit and stand can change the way we think and speak.” The goal of being an embodied coach inspires us to cultivate our ability to be present to our whole self: head, heart, and gut. A coach able to ground oneself and remain centered in the midst of difficult times and challenging engagements is equipped to manage whatever presents itself in the coaching engagement.

I freely admit I have been slower than most to experience the wisdom of my body. I was one of those who revered the mind and thought my body was just along for the journey. Today, I find enormous value in cultivating my embodied self, engaging in daily centering practices, and learning from the wisdom of my body that often far exceeds my mind! My revelations about my mind-body disconnect happened a few years in a most unusual way well outside the bounds of coaching. I have been exploring the world of clay, pottery wheels, and kilns for nearly a decade. My progress is slow, in part because I am only able to devote small chunks of time to this work because of other commitments in my life, but what seems to impede me even more than time is myself, my way of connecting to the clay, and the work. Like any learning, the power of a great teacher or mentor is immeasurable, and over the past two or three years, I had the gift of two such teachers. One, in particular, had the knack of combining candor with light humor and the combination is just enough to create small cracks in my old habits that allow for new learning and far better ceramics!

Get Out of Your Head!

I have heard this message—“Get out of your head, Pam”—bellow from my ceramics teacher from across the room over and over in the past couple of years. Other students in the studio snicker a bit and initially, I cringed wondering what, precisely she wanted me to do. Now, I get it. My goal in my work at this stage is simple and seemingly impossible. I want to throw the clay in such a way that I am able to pull up broad, thin walls. What I’ve learned is that in order to execute this simple yet difficult act I need to be fully grounded in my body, the tips of my fingers, my breathing, and my posture. When I am in my head judging my work, planning for how it will look or dreaming about a stunning bowl, things go badly! When I am in my body, magic happens; I feel the rhythm of the water racing through my fingers as I slowly draw the sides of a bowl up and out. I am centered in my body, spellbound by the power of this sort of presence to the moment, to the clay, the water, and the hum of the wheel.

In my first years of sitting at the wheel and attempting to throw a pot, my body was completely disconnected from my brain, my thoughts were in charge, and my body was in a habit. When I am in this new centered and embodied state in the studio, everything changes inside me and in the work I am able to do. This is true whether creating a bowl in the studio, coaching a client, or living our day-to-day lives. M.C. Richards long ago wrote a wonderful book I regularly reread: Centering: In Pottery, Poetry and the Person (1964). It’s about pottery, our bodies, and our humanness, and it parallels our work as coaches beautifully. Here is my favorite quote from the book:

As human beings functioning as potters, we center ourselves and our clay. We know how necessary it is to be “on center” ourselves if we wish to bring our clay into center. Tensions in the fingers, in the arms and back, holding the breath, these things count. The potter has to prepare her body as she does that of the clay.

Powerful words from M.C. Richards; they suggest that to do our work, we need to be centered and we need to embody our self, whether as a potter, a coach, or a leader. The realm of embodiment and somatic awareness is also inextricably connected to presence: presence to our inner chatter and presence to the third entity. The potter’s chatter is often in the form of: “My wall is too thin, my clay feels off center, I’m working too slowly, and I’m pulling too quickly.” It’s the same in whatever our art is—our internal chatter throws us off center.

When coaching, how often have you lost your center by asking one or more of the following of yourself?

- Am I asking the right question?

- Am I hitting the mark for my client?

- Wow, my client’s perceptions seem way off. How and what would be my best move here?

- I’m aware of feeling annoyed. How do I get my self back to us?

This is where my ceramics teacher, if a master coach, might holler, “Get out of your head!” This is the power of developing practices that allow us to observe ourselves. Our brain is connected to our body. Sensations are experienced first in our body and only later interpreted in our brain. Yet, many of us worship the brain and ignore the wisdom of our body. Embodiment is all about how we live in our body and allow our body to be the center from which we interact and move in the world.

Honing Our Felt Sense and Our Somatic Markers

Allowing our body to be the center from which we interact requires us to hone a felt sense of our self. Scientists often refer to this as proprioception: the ability to sense and respond to stimuli in our body without the aid of our visual perceptions. This is sometimes described as a sixth sense.

Somatic Markers

Antonio Damasio (1994) coined the term somatic markers to suggest feelings in our body are connected with particular emotions. If we are living mostly in our head and disconnected from our body, the chances are our associated emotions are a combination of stress, rushing, planning, worrying, and so on. The ingrained ways our unique bodies each respond to life, stress, and the unexpected is built into our muscle memory and the way we hold ourselves. Some of us may shrink, cave in our shoulders a bit; others may puff up the chest; some of us enter a difficult conversation with a frown or an over-smile. Whatever our conditioned responses or somatic markers might be, they are cultivated over time, connecting sensations to feelings and causing a certain set of muscles to contract or a particular posture to be assumed, or a way of breathing (shallow, slow, quick) to take hold. We tell a story about ourselves through these markers and as Wendy Palmer reminds us, “The way we sit and stand can change the way we think and feel.” In other words, our emotions ultimately create the shapes we become as adults.

What a loss it would be for us in our own development as coaches and in our work with our clients if we ignored the wisdom of our body and insufficiently cultivated attunement to our felt self; and what a loss for our clients if we are unable to harvest the wisdom of the body to support our work.

The work of those who have dedicated themselves to this field of study seems to reliably draw our attention, first, to the shape of our self—our somatic markers. Finding our breath, using our breath to center and ground ourselves, and integrating all of this allows us to reliably return to our body as our main source of wisdom and feedback.

Becoming Self-Generative

Doug Silsbee (2008) explained it this way: “When we are self-generative, we have the capacity to be present and a learner in all of life in order to make choice from the inner state of greatest possible awareness and resourcefulness.” The ability to be self-generative significantly increases our capacity as coaches to be resilient, fully aware, and awake and ready to learn again.

Centering Ourselves

Centering is an internal practice of bringing our full attention to our body and all of our body’s sensations, aligning our body to the three dimensions of space in which we live: depth, length, and width. There are many variations on this centering practice, and it’s probably optimal when we each customize it to make it work best for one’s self. With each of these three dimensions, I’m including a practice to experiment with. However, know most of all that this needs to work for you.

First, Finding Our Length and Our Dignity

Most of us are physically aligned to what we’ve become accustomed to over years of habits, including any variety of stories—the head is well in front of the body, the shoulders are collapsed, the gut is forward of the head, head and shoulders are leaning back. It takes the eye of a keen observer to help us see where we are out of alignment as we work to find our length. The rhythm is extending upward and relaxing downward. Lengthening and softening repeatedly.

A Practice for Finding Our Length

This particular practice is one I came across while reading Peter Hamill’s book, Embodied Leadership: The Somatic Approach to Developing Your Leadership (2013). This same practice likely occurs in several other sources, as well.

First, finding your length by standing up with feet about shoulder-width apart, arms by your sides and eyes wide open. Imagining a string threaded through your body elongating your spine upward and relaxing downward feeling the power of gravity, too.

Next, Hamill offers the image of a series of bands we have running up and down our body from top of head to bottom of feet. We each loosen and tighten these bands through our experiences, emotions, and habits, so the practice of slowly experiencing each band can reveal some of our best honed habits. A stop at each band allows you to notice any tension, to experiment with releasing tension and to perhaps notice some bodily nuances often outside your awareness.

At each stop you might practice holding tension and releasing a few times to see what you notice:

- Band One: The Forehead—Some of us hold a lot of tension in this area either with furrowed brows that can give the message of worry or anger, or raised brows that might signal surprise or fear to others.

- Band Two: The Eyes—The level of tension or relaxation in our eyes takes many forms: hard eyes, glazed, peering or searing, and open and relaxed.

- Band Three: The Jaw—This powerful muscle is capable of holding so much tension it can result in teeth gnashing in the night. When the jaw is fully relaxed our back teeth are not touching. This leaves the mouth just slightly ajar. When we hold a lot of tension in our jaw, our lips purse a bit—hence the phrase grin and bear it.

- Band Four: The Shoulders—Another common place to store tension whether it is that our shoulders are raised up nearly touching our ears or our arms are held out from the sides of our bodies; both of these positions take a good deal of energy to maintain.

- Band Five: The Chest—Some of us collapse our chest or jut out the chest and either requires energy, making it difficult to maintain access to our heart.

- Band Six: The Stomach—Often a place in our body where we hold emotions. Finding ways to soften, and imagining a soft belly allows us to let go of added tension.

- Band Seven: The Sphincters—Another common place to hold tension, we often use the term anal to suggest someone who is uptight. Imagine loosening these muscles.

- Band Eight: The Legs—Tension is often stored in locked knees that make it harder for us to relax our legs. Practicing a softening of the knee loosens tension we might hold here.

- Band Nine: The Feet—Tension is often evidenced in continual tapping and moving of the feet. Letting go of this attention allows us to feel the Earth and let gravity support us more fully.

Standing tall and relaxing downward into the body. Imagine taking the few minutes needed to do a body scan of these nine bands a few times each day. Imagine what you would learn about where you store your tensions and how you might change the way you stand if some of that tension were released even just a bit.

Second, Finding Our Width and Our Connectedness

Pay attention to the space on either side of yourself: your width. Experiment with how much space you take up out of habit and whether or not you would like to broaden your width or pull it in a bit. This is our social dimension, our connectedness with others. If we use very little of our width, we may have a tendency to play it too small in our own world, and if we use too much we may veer into the space of others.

A Practice for Finding Our Width

Rock side to side and gain a sense of the comfort zone of your space and your width. Do this several times throughout the day for a few days, noticing where your natural comfort zone seems to be.

Third, Finding Our Depth, Our Support, Our Ancestry

Find the balance point between present and future. Rocking gently back and forth can help to locate your balance point. Too often we are focused on what is in front of us but we ignore the space behind us. Doug Silsbee (2008) had this wonderful metaphor for the space behind us: He termed it “our dinosaur tail,” meaning our history, our ancestors, our heritage, our culture, and all who have supported and continue to support us in the world.

A Practice for Finding Your Depth

Who’s got your back today and through the ages? Metaphorically, who can you lean on today and in your history; who is in your “dinosaur tail”? Take some time to reflect on this. Make a list of those from your ancestry, those in your past and those today, some who know you well and some who may be iconic figures you admire by virtue of their example in the world.

Centering and grounding ourselves and focusing on our length, width, and depth is a practice we can engage in that allows us to consciously embody our self. This is a place to start and a place to stay in this work.

THE COACH’S WORKSHEET: DEVELOPING MORE RANGE

Visit www.selfascoach.com for an opportunity to step back from each chapter and reflect on what meaning it has for you and what practices you might develop to keep honing your capacity as coach.