Chapter 9

Courage

You cannot swim for new horizons

until you have the courage to

lose sight of the shore.

—William Faulkner

Courage Has Many Forms

Faulkner says it well—it takes courage for us to lose sight of our shores. If we don’t let go of what we know, our capacity to reach new horizons is greatly constrained. This concept of courage has roots in our earliest recorded human writing and the meaning of the concept has depth and nuance. Today, writer and philosophy professor Daniel Putnam (2004) considers three kinds of courage: physical, moral, and psychological. It is the third kind that we will look at most closely for its relevance to the work of coaching.

First, a few words about physical and moral courage. Physical courage was at the heart of the ancient Greek sagas of courage in the tales of Odysseus and others. Odysseus’s courage was predominantly of a physical nature, as it entailed enduring a 10-year struggle to return home to Ithaca following the Trojan War. Each stop along his journey was fraught with physical dangers requiring enormous courage as he battled mythical beasts and the ire of the gods. Modern-day versions of physical courage are equally daunting. Think of the courage of the 70 million refugees in our world today who continue to put another foot forward walking across continents, searching for a safe place to exist.

Moral courage is the kind fueled by a passion and commitment to an ethical compass deep within. Nelson Mandela was among icons demonstrating this sort of extraordinary courage. He became the first black president of South Africa after spending 27 years in prison where he was confined to a small cell without a bed or plumbing, forced to do hard labor in a lime quarry. Upon release, he promoted a message of forgiveness and equality throughout the culturally torn country. The recipient of the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize, he is often quoted as saying, “There is no passion to be found playing small, in settling for a life that is less than the one you are capable of living.” Malala Yousafzai was only 15 years old when she demonstrated remarkable courage as a gunman boarded her school bus in Pakistan shouting her name. Instead of endangering others and remaining silent, she stood up and said, “I am Malala,” whereupon he shot her three times in the head. Miraculously, she recovered and continues to demonstrate enormous courage based on her moral convictions. Malala is often quoted as saying, “I raise up my voice not so I can shout but so that those without a voice can be heard . . . we cannot succeed when half of us are held back.” In 2014, Yousafzai received the Nobel Peace Prize.

Psychological Courage

The third form of courage is a psychological courage, described as “overcoming the fear of losing the psyche, the fear of psychological death” (Putman, 2004). This form can also be characterized as the willingness and courage to face up to our inner fears and long-held habitual ways of being. This psychological courage is most relevant to our work as coaches because to do our best work, we need a willingness to confront our own fears in order to be of service to our clients.

The work we do and the relationships we forge with our clients demand the best of what we are capable of as coaches. Leaders seek coaching because they want to make some changes pivotal to their way of being as a leader, changes that they are simply unable to live into on their own. Why? Because like us, they are human and unable to fully grasp or gain a view of their blind spots, well-worn patterns, and the habits that served them in the past and hinder them now. To meet leaders where they need us most, to reach for new horizons with our clients, requires us to be courageous. We are traveling together in new territory, uncovering old, mostly invisible habits and stories, and examining together things that have been unspoken. This work is not for the faint of heart!

Cultivating Our Courage

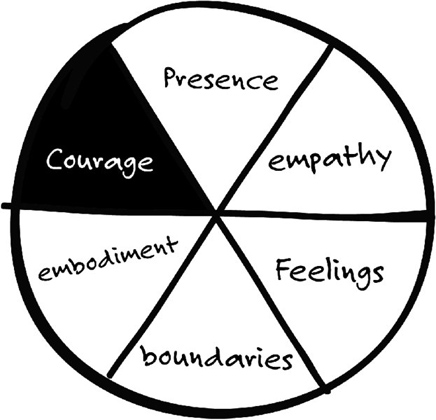

Our willingness and capacity to cultivate courage is one of the hallmarks distinguishing good coaches from great ones. To have courage as a coach we need to bring all of the other elements of Self as Coach to bear:

- We need our full presence to spot opportunities to exercise courage in our coaching.

- Well-balanced empathy allows us to express a courageous comment or observation with heart in a way that invites the client to consider it.

- Access to the range of feelings expressed by the client allows us to meet the client where they are.

- Strong boundaries prevent us from getting drawn into the client’s story and instead courageously observe the story so the leader and coach can learn together.

- Centering ourselves and focusing on embodiment allows us to stay strong and attuned, and provides a steady support when we feel wobbly about proceeding when the stakes are highest.

Throughout the exploration of Self as Coach, I have often used the phrases “using what’s in the room” and “turning up the heat.” These phrases signify our ability to use courage as an access point to create the conditions for change to unfold. Both using what’s in the room and turning up the heat act as courageous invitations for our client to see something about self with fresh eyes or first eyes.

My Interior Journal: What I’ve Learned About the Power of Courage

I will forever remember working with a coach in the midst of some tough and tricky situations that had emerged early in my role as a leader. I was so certain the issues at hand were not mine, and I was probably exhibiting that righteous indignation that can show up at these times! My coach stopped me and with heart and lightness asked me, “Do you notice what you are saying? It’s all about others. I wonder what this says about you and if you are willing to take that path for a bit, as well.” Powerful, courageous, and inviting. The moment turned out to be pivotal in changes I made in my leadership style and monumental in how I viscerally understood the power of courage. There are so many ways she might have made this observation or shared a pattern she was seeing in my words and she chose heart, lightness, and an invitation. No judgments, no challenging my thinking, no rescuing me, no triangulating. She used what was in the room in that moment and turned up the heat in a manner that allowed me to step into new possibilities.

Our Courage Creates an Invitation

The question of what is demanded of us as coaches in order to engage in courageous acts in our work is deeply personal. That which is personal leads back to our own attachment styles, level of development, and willingness to engage in our vertical development. In other words, have we cultivated our internal landscape sufficiently to allow us to develop our courage? Courage grows in the choices we make and the actions we undertake every day in our work. Our willingness to speak our truth, to share an important perspective or observation, to be candid when it matters, or to be provocative in order to help a client gain another perspective—these are acts of courage, demonstrations of going bigger, and signs of resisting the urge to retreat to the shore and avoid the new horizons. A coaching colleague and master coach, Tom Pollack, has often said, “Courage is an invitation that taps you on the shoulder during a coaching session and says, ‘Bring this up with the client,’ even though you would prefer staying safe in the moment.” The truth is, when we refuse the invitation to step into that courageous space with our clients, both of us lose.

DEEPENING YOUR IMPACT: BUILDING MORE COURAGE

- Pay attention to patterns that emerge in the situations and stories discussed in coaching and find ways to bring up what you notice using heart and courage.

- Build comfort in sharing observations that stand out in a coaching session—things like making little eye contact, watching one’s smartphone, constantly tapping a foot, apologizing repeatedly, using a phrase (I’m just not lucky, etc.) with a high frequency, showing up late to several coaching calls, continually cancelling coaching sessions, and so on.

- Develop ease using what’s in the room and exploring this with the client. This might be pointing out how a client moves rapidly from one topic to another in a disjointed way or talks in a circular manner making it harder to connect the links.

- Practice using silence as a way to create a bit of heat that will often give the client enough needed time to uncover something important that might not surface if we fill these spaces with small talk or comments.

Fear and Lethargy Thwart Courage

For many years, our team of faculty at Hudson has come together for an annual retreat to renew, recalibrate to be at our best in our coaching work with others, and learn from a master. At a recent retreat, we spent a day with one of those masters, James Hollis, well-known Jungian analyst, professor, and author of numerous books. He focuses on the complicated internal landscape of humans and threads the concept of courage throughout his work. On that day, Hollis modeled courage as he boldly provoked and prodded precious beliefs and biases we held about our lives. One story he shared linking to courage goes something like this (sic): “Every morning when we awaken and look about scanning our surroundings to find our bearings, we are confronted with two beasts at the foot of our bed, comfortably perched on each of the bed posts. One beast is LETHARGY and the other is FEAR.” Each day as we awaken we make choices about whether to cave to the powerful forces of one or both of these beasts, whether to slump back a bit and take the easier road that doesn’t require so much of us. The voice of fear encourages us to stay small and cautions us that we are not prepared to take any risks. The voice of lethargy is, in Hollis’s words, the more seductive one telling us to chill out, we’ve done enough, take it easy, have a glass of wine, watch a sitcom, that’s good enough. There is a universality about the voices of lethargy and fear we all share. Growing our psychological courage requires that we wake up to our internal voices and the messages of fear and lethargy that sustain old habits and routines.

Learning to Rock the Boat

Our capacity to develop a heightened awareness of these two beasts that seem to magnetically pull us toward comfort, habit, and safety, is one of the important ways we build our psychological courage, that essential cornerstone in great coaching. The coach may have a fear of rocking the boat when the engagement is mostly going just fine; or they may fear that a courageous comment could alter the relationship and the client’s view of the coach; or they may have a fear that says, I, as coach, will not be liked as much by my client, or a bold comment could ruin my rating or risk additional work. The bedpost of lethargy continually tugs at us and the familiar inner chatter is saying, Why take the risk? I’m at home with my current approach. Why take a chance? This is good enough as is.

Building the capacity to call on our courage comes with time, experience, collegial and supervisory input, and life experiences. In Hollis’s most recent book, Living an Examined Life: Wisdom for the Second Half of the Journey (2018), he offers series of 21 desiderata to courageously make our life more of our own with a stronger sense of agency and a willingness to play bigger and risk more. His opening desiderata is provocative for all of us: Grow Up. Whatever it is we are shirking away from, whenever we find our old habits and ways of being sufficient in this world, we are taking the easy path. Grow Up can remind us as coaches that we need to ground ourselves in our values and go bigger, lean into the unknown, and resist the call of lethargy.

Often our opportunities to grow up, stay awake, and demonstrate courage are found in small micro-moments of everyday life. When we are alert to these moments and we lean into them we strengthen our courage muscle. It may be that small moment of providing feedback to another that may be hard to hear, or that opportunity to take a stand on an issue that matters to you, or the willingness to offer an opposing view in the face of disagreement. Courage requires that we set boundaries and say no when it matters. It takes courage to say no and sometimes even more to say yes.

DEEPENING YOUR IMPACT: RECALL SMALL ACTS OF COURAGE

You can likely scan the last few months and identify moments of courage, small acts that required you to take a stronger stand than usual. Perhaps it was a refusal, a no to a request, or a decision to take action that rested on your shoulders, or a yes to leading an initiative that’s a little outside your comfort zone. These small acts of courage are supported by our values, ethics, and sense of what matters most at this time in your life. Then there are the larger acts. Taking a public stand in the face of opposition, leaving a great work role to pursue a risky dream, setting a very tough limit with a family member. The continual cultivation of small acts makes the bigger ones possible.

Leaders Need Courageous Coaches

Leaders seek out a coach because something is not working as well as they and others would like it to work. Leaders come to us because stakeholders have put a spotlight on a blind spot that is a barrier to success. They appear out of a desire to continue to grow in their roles and career paths and often the obstacles and blind spots are not at all clear to them. If these leaders could pick up a book, an article, or a tool and rapidly make the adjustments they need to live into, they would be doing so! It takes courage for a leader to seek out a coach and when a leader comes knocking, they deserve the coach’s courage to help them look at that which is invisible or only marginally accessible and uncomfortable to explore. This is what others do not and will not do; this is what is needed to help leaders grow and deepen their capacities and this requires grit and courage on your part as a coach.

Turning Up the Heat and Demonstrating Courage in Our Coaching

Demonstrating courage takes many forms in our work as coaches. In Table 9.1, I expand on a handful of common courage pivots.

Table 9.1 Common Pivots to Courage in Coaching

| Common Coach Scenarios | Coaching + Courage

|

Impact on Coachee’s Development: A Coach’s Reflections |

Late Again The client routinely shows up late for appointments and cancels from time to time at the last minute. |

“John, I’ve been noticing something I think could be useful for us to explore—are you up for that? Great. Over the past two months you have been 15–20 minutes late for most of our sessions, twice you’ve canceled at the very last minute. It’s got my attention because it is such a regular occurrence and I wonder if what is happening here might be worth some exploration. Are you up for that?” | John expressed surprise and little awareness of his lateness behavior. While I shared how it impacted me, I put a bigger focus on wondering how it might be occurring with his team and wondering what impact that might have. This opened the door to a pivotal focus on how he shows up as a leader of his team, how his team experiences his routine tardiness, and the powerful message embedded in this behavior that was out of his awareness. |

The Talking Is Non-Stop The client has a habit of talking nonstop almost without taking a breath, adding one sentence after another and in the process making it hard to track what’s important or at the core. |

“Marge, could I stop you for a moment and ask you to step back for a bit and reflect?” I’m aware that you’ve been talking pretty much non-stop for the past several minutes and I’m starting to get lost. I find myself wondering if you have an awareness of this and if we might this explore together?” | Marge wants to be considered for a promotion and she has received feedback she does not show up as a leader. Turns out her habit of talking nonstop thoroughly diminished her presence and others lost interest in what she was saying. The courage to use what was in the room and explore the pattern the coach observed was a turning point in the work. |

It’s All About Me, Me, Me The client has a habit of bringing everything we explore back to himself, using himself as the reference point for all that he experiences and describes. |

Jack, you’ve said a lot about you, could we step back and play with what you imagine this is like for the four folks on your senior team? | Jack wants to be a strong and respected leader of his team. His stakeholder feedback has a singular theme: It’s always about Jack. When we reviewed the feedback, he was surprised and not aware of this dynamic. The courage to share this in the session allowed Jack to get a glimpse of what his people experience. |

I’m Hearing Victim-Talk This client is unable to see her role in situations that occur within her team. She finds it easier to blame than take responsibility for what she might be contributing to the situations. |

Anu, I wonder if you would allow me to share a pattern I’m hearing often over these last three sessions? I hear you saying things like, “Why do bad things always happen to me?” or “I just have a lot of bad luck.” These are powerful statements—I wonder if you are aware of how often you say these to yourself? | Anu’s inability to see her victim-like language in the coaching conversation provides powerful input into a blind spot that she hasn’t seen. Left unchecked, her development will be stunted. |

That Pace Is Intense This client arrives at coaching concerned that he is not getting advancements he would like and unable to see what the obstacles might be. Stakeholder input centered around his pace and intensity. |

Coach: Steve, would you allow me to share what I’m noticing?

Steve: Sure, go ahead. Coach: I keep noticing this intensity in your voice as you speak—your voice is strong, loud, and there is a pressured quality, a speed at which you speak. I notice my own heart rate picks up and I start to feel a little anxiety internally and I wonder if this happens in other places and if it’s worth our exploration? Steve: Wow, I’m really not aware of what you describe, but it is similar to what showed up when you did my stakeholder interviews, isn’t it? |

A big part of my focus with Steve was around his approachability factor. His team simply did not experience him as approachable. Turns out what I experienced inside our coaching sessions was very similar to what others experienced, yet no one was willing to share this feedback with Steve and it was outside of his awareness. As we started to explore this when it showed up in the coaching sessions, Steve was able to palpably understand what was occurring in him and how it was impacting others. |

Five Truths About Courage

- Connect Heart to Heat: The power of courage is enhanced when we use empathy. When we connect heart to heat, something happens that is otherwise impossible. There are so many ways we can exercise courage and make an observation or comment that our client is simply unable to hear and instead what shows up is defensiveness.

- Use What’s in the Room: Using what is right in front of us creates heat and opens the door to rapid insight because it is in the here and now. It is not a concept or an abstract notion we are talking about. This quality of immediacy creates a powerful medium for breakthrough learning.

- Lighten It Up: We can invoke the wise fool or jester, the one who speaks the hard truths that no one else will utter. When we cultivate our wise fool, we are able to explore difficult issues almost in jest, so the client can hear and entertain new vantage points. A jester-like approach allows us to look together at that which is being ignored and unspoken.

- Stay Out of Your Client’s Story: Good boundaries keep us alert to any tendency to get drawn into our client’s stories and dramas and this is how we lay the groundwork for helping the client see their stories. If we are in them, we can’t help them!

- This Is Our Work as Coach: This is our work, this is why leaders come to us—to see that which is invisible and to make changes that will allow them to be even more effective. When we stay out of their stories and, instead, help them see their stories and behaviors through the use of our own courage, we do our most important work as coaches.

THE COACH’S WORKSHEET: DEVELOPING MORE RANGE

Visit www.selfascoach.com for an opportunity to step back from each chapter and reflect on what meaning it has for you and what practices you might develop to keep honing your capacity as coach.

Applying Heat: Case Vignette III

CASE VIGNETTE #3: RESISTANT BUT RELIABLE

You’ve entered into a coaching engagement with Kye. His boss has recommended this coaching because he is aware of a lot of buzz and some complaints in the system that Kye is very bristly and abrupt with others. His boss finds Kye to be exceptionally smart and able and he wants Kye to address this issue in order to continue to expand his role. Kye arrives at coaching willingly, although he is surprised this is an issue and believes it is a misperception of only a few people. You complete a round of stakeholder interviews and return to the coaching engagement reporting that this theme of bristly and abrupt (some even using the term rude) is widespread among all who report to him. Kye again reacts with surprise, suggesting these stakeholders are overreacting. As the coach, you are aware of feeling Kye’s resistance to this input.

Coach 1

Coach 1 was worried at the contracting stage of this coaching arrangement. It was clear Kye’s boss was onboard to provide the coaching and Kye seemed willing at the time but now this coach has a sense that Kye has little interest in the coaching. He finds him a bit bristly, too, and worries he will not be able to have a successful engagement with him and wishes he hadn’t agreed to the work.

Where Coach 1 Is in Each of the Six Dimensions

- Presence. The coach appears to be preoccupied with worries about whether or not he should have taken on this engagement and this likely degrades his ability to be fully present.

- Empathy. The coach mentions that it is not easy to build a connection with Kye and we don’t have enough detail to know how much of that is related to the client and how much to the coach.

- Range of Feelings. The coach is aware of his own worries, but his reflections don’t mention much about Kye’s feelings.

- Boundaries and Systems. The coach may well have good boundaries with this client, but his primary attention is focused on concerns and worries that coaching will not succeed, so there aren’t sufficient reflections to allow us to observe boundaries.

- Embodiment. The coach doesn’t offer any comments relative to how centered or grounded he might be during the sessions.

- Courage. The coach is not able to exercise courage. He does mention that Kye feels bristly to him in the coaching, but perhaps this is because he is focused on his worries or because the connection (empathy) is not strong enough; he does not share any observations or focus on “what’s in the room” in the moment.

Coach 2

Coach 2 knows the coaching can always be a little trickier when it is the boss’s idea, yet she finds Kye willing and believes she has built a good working alliance with him. After gathering the stakeholder input, it’s clear Kye has some significant blind spots and the coach has a sense this is going to be very important for his future in the organization. She feels an urgency to dig in and help him figure out what he can change to be viewed differently, and yet, she experiences his reluctance. She resists offering her ideas about how he might make some adjustments, but she finds herself increasingly frustrated that he doesn’t seem invested and doesn’t seem to see how serious this might be for him.

Where Coach 2 Is in Each of the Six Dimensions

- Presence. The coach appears to be fully present according to her description of what unfolds in the coaching work.

- Empathy. The coach reflects on her working alliance and believes she has developed a good connectedness.

- Range of Feelings. The coach seems able to fully appreciate and contain her client’s feelings.

- Boundaries and Systems. The coach has gathered input from the system in order to gain a wider view of what Kye’s boss reports. While the coach is tempted to get into the client’s story (dig in and help him), she resists, and this is a sign of some managing of boundaries in order to help the client see his situation more clearly.

- Embodiment. The coach doesn’t offer any reflections on how centered or grounded she feels during the coaching sessions.

- Courage. The coach is able to notice and observe how the client is showing up—not as invested in making a change, not taking the feedback very seriously. However, the coach’s focus on getting him onboard is a sign she is a bit drawn into her client’s story. Once in the client’s story, it is always hard to step back and use one’s courage to share an observation that might be of value for the client.

Coach 3

It’s clear to Coach 3 at the outset that the boss is more invested in the coaching than Kye, yet Kye is willing and so he says yes to taking on the engagement. Once he has gathered the stakeholder input, he realizes the boss might actually be underestimating the impact of Kye’s behaviors and it’s clear Kye is either unaware or in some denial about this. The coach decides to go slowly because it seems much of this behavior is outside of his awareness. He takes his time exploring what’s working and what he feels best about and as the rapport grows, his resistance lessens and he seems interested in addressing or adjusting his behavior.

Where Coach 3 Is in Each of the Six Dimensions

- Presence. The coach seems to be fully present, managing any internal chatter attending to how his client views his situation and the stakeholder input.

- Empathy. The coach reflects on his working alliance and believes he has developed a strong rapport. In addition, the coach is attuned to creating a pace that will match his client’s needs as he actively continues to deepen empathy and rapport as the engagement proceeds.

- Range of Feelings. The coach appears able to fully appreciate his client’s feelings and his lack of awareness of the feedback he received in the stakeholder input. He notices Kye’s surprise and his inclination to deny the input.

- Boundaries and Systems. The coach is able to maintain strong enough boundaries to avoid any temptation to rescue or collude with Kye. This allows the coach to explore the feedback in a nonjudgmental manner that allows Kye to begin to gain awareness of these areas.

- Embodiment. The coach is so present to Kye in this coaching engagement that one might guess he has some in-the-moment practices that support him in being fully centered and grounded during the sessions.

- Courage. The coach is able to turn up the heat just enough to invite Kye to examine the feedback around his bristles. He mentions he is attending to timing and that is important when sharing observations or courageous transparency.

A BRIEF EPILOGUE TO THE CASE VIGNETTES

In each of these three coach approaches, I have amplified the coach’s use of self in order to put a spotlight on how interconnected the six dimensions of Self as Coach are in our work. There is never one right way or a prescriptive approach to developmental coaching. The sole focus of this book is deepening one’s coaching capacity by continually cultivating one’s internal landscape in order to ably use self as the most important instrument in the coaching engagement.

Presence is a prerequisite to a successful engagement. The impact of unmanaged inner chatter, judgments, and assumptions is an enormous obstacle in seeing the client as they are rather than as a coach might wish them to be. Embodiment work that dependably supports a coach in getting one’s self together, getting centered and grounded, supports this all-important full presence.

Empathy is fundamental in coaching. Without the ability to step into a client’s shoes (without walking in them!), the engagement lacks a sense of psychological safety and trust that is needed in order to explore what’s most important. Empathy is also essential when a coach uses courage in a way that may open new perspectives and new ways of seeing for the client. Courage with heart creates an invitation instead of a judgment.

Feelings are essential in coaching, as we will never change by intellectualizing or talking about a dynamic. It is in the mix of thoughts and feelings that breakthroughs occur. This means attending to feelings, noticing small signs of feelings, and staying a little longer to explore is important ground in the work of coaching.

Strong boundaries allow a coach to resist colluding and withstand the urge to don a cape and rush in to do the work for the client. When the coach has firm boundaries, they are able to more clearly observe the client’s patterns and stories, and this combined with the use of courage and empathy turns up the heat for the client to see their circumstances, beliefs, or behaviors with new eyes.