Chapter 10

Supervision as a Medium for Cultivating Self as Coach

The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.

—Marcel Proust

The work of a coach is, by its very nature, insular. Whether practicing as an internal coach, as a team coach, or as a leadership coach interfacing with stakeholders, the essence of our work happens within the confines and dynamics of the coaching relationship. How do we stay alert to all that is unfolding? How do we uncover what is only vaguely emergent? How do we ask of ourselves what we ask of our clients—to observe, go deeper, risk letting go of the old, and lean into the new territories of the self?

Any good coach would agree that the quality of one’s coaching is enhanced through reflective practices—the simple act of stepping back, reviewing what has transpired and asking what else might have happened, what might have been missing, and what got in the way of getting to the most important work. Yet, without a deliberate practice this can slip out of our awareness and we can rely on our old eyes instead of sharpening new ones. The tyranny of our habits, the pressure of time, and the addiction to busy-ness will inevitably prevail unless we are fully committed to turning up the heat on our own work as coach.

Coaching supervision provides this space to consciously step back and look at our work through different lenses with refreshed, sometimes new, eyes. It is here where we can deliberately focus on deepening our capacities to see, sense, hear, feel, and intuit that which lies in the margins of our awareness. This is a practice: a conscious and deliberate choice to reflect on our work in order to be at our best. Anyone who has been coaching for a time knows how universally common it is to return to a coaching session and in retrospect find oneself noticing, wondering, or perhaps worrying about what occurred at a particular moment in the session. Common reflections I have uttered myself and heard repeatedly from those in my supervision groups often sound like this:

- Something happened in the session that left me feeling uneasy.

- I felt like we didn’t land on what was most important; we seemed to be talking around it.

- I was mindful of my own tenseness, sensations I’m not aware of in most coaching sessions.

- I knew I was missing an opportunity, but I was unsure in that moment of how to proceed.

- We both experienced a breakthrough moment, but I’m not sure what created it.

My Inner Landscape: My Early Experiences in Supervision

My own experiences of the power of supervision preceded the field of coaching when I was immersed in my early professional career as a clinical psychologist. In the world of psychology, supervision has long been a standard method of development at all stages of one’s career. It is viewed as an essential practice in order to be at one’s best; it is an ethical practice. Finding a wise and skilled supervisor is a goal and I was lucky to have the gift of working with an analytically oriented supervisor, Dr. Brams, trained and supervised by Erik Fromm in his early years. Dr. Brams was a provocative and wise analyst and supervisor. Throughout my 30 s and into my 40 s, I would drive out to his office regularly and explore cases and situations through new lenses. As my experience and confidence grew, I would wonder on the drive out to our session what I might learn that I wasn’t capable of seeing for myself and on my return home, I would chuckle, reflecting on all I had not seen in my work, not because I lacked experience but because I am human. We will never see all there is to work with in our engagements, and we will inevitably lose track of our own stories and endless assumptions we make as people and as coaches. Expanding our view and learning to see what is hazily on the fringes is what supervision is all about. We are complicated human beings and as coaches, we are served by knowing our best reflective work is not done in isolation.

Supervision Purpose and Modalities

The reflective practice of supervision provides a medium for us to develop new ways of seeing and gain new perspectives on our work. Supervision is the term we have come to use to describe this structured practice of reflecting on our coaching work along with a trained coach supervisor equipped to support the growth and development of a coach at any stage in their career. For some of my colleagues, the term supervision is offputting and misleading. The term supervisor seems to convey for them a power dynamic and an evaluative format they find uninviting. Indeed, their reaction is understandable. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines supervision as “the act of critically watching and directing.” This definition is a far cry from the focus and purpose of the practice of coach supervision and the term does not accurately convey the essence of this powerful practice. North America was late in incorporating a structured reflective practice supporting a coach’s ongoing development; other parts of the globe had already fully embraced it and termed the process supervision. Thus, for coaches in the United States, it was too late to impact the words used to describe it. So here we are—coach supervision it is.

Roles of the Coach Supervisor

The purpose of supervision aligns with the roles of the supervisor. There are several models for the supervisory roles that overlap and align. I find Erik de Haan’s (2008) framework outlining three supervisory roles serves as a helpful foundation for us. His three roles include:

- Developer: In this role, the supervisor provides her summary of the situation being presented along with any observations, patterns, or links she makes to what is being presented. The focus in this role is solely on the coach’s development.

- Gatekeeper: In this role, the supervisor views it as their responsibility to be the gatekeeper for the profession of coaching and in those rare situations where ethical boundaries are not heeded or the coach’s approach is outside the parameters of coaching, the supervisor makes this known to the coach and together they develop a course of action that protects the client, the profession, and ultimately, the coach going forward.

- Nurse: In this role, the supervisor works to create a restorative space for the coach through creation of a safe space that emphasizes encouraging and approachable interventions that allow the coach to grow, thrive, and stretch their capacity.

Formats for Supervision

In addition to purpose and roles in supervision, there are several common formats for this work, each having some unique qualities, advantages, and potential downsides.

Group Supervision

This is a format that typically includes a supervisor along with four to six coach supervisees meeting monthly for a 90- to 120-minute session. On occasions when in-person sessions are possible, that is ideal; but most often this occurs via web video calls allowing group members to see one another onscreen during the course of each call. Coach supervisees use the time to discuss a part of their coaching work, a pattern or theme they are noticing, or something unique to themselves as related to the coaching work. This format allows for a combination of work with the supervisor, insights and observations from other group members, and links to common ground uncovered for all in the course of any of the discussions that ensue. The coach supervisee might bring to supervision a moment in a session, a transcript of a portion of a session, a recording of a portion of a session, a written free-association of a session, or any other format that proves helpful to the coach. The group interaction brings richness to the supervision and allows members to learn from another’s case or challenge as well as from their own situations. The drawback for some is there is less time for 1:1 focus and that is sometimes an important consideration for the coach.

Individual Supervision

This format is highly personalized with a 1:1 approach. All that occurs in group supervision occurs in 1:1, with an individualized focus between coach and supervisor. The drawback for some is there is not an opportunity to gain input and insights from other colleagues nor is there the opportunity to learn from the cases and challenges from others.

Peer Supervision

This approach can be a preferred alternative for coaches with substantial experience in supervision and perhaps as coach supervisors. It is also commonly recommended in group supervision that the group meets once each month as a peer group in addition to the supervisor-led monthly call. It’s also common for those coaches experienced in supervision to engage solely in peer supervision.

Inner Supervisor

This approach is one we can all draw upon at times and, in fact, engaging our inner supervisor is a powerful tool we can invoke for our own development at all times.

There are a variety of models and approaches to coach supervision referenced later in this chapter, and given that the original sources are well known and widely available, my primary focus in this chapter is on cultivating the inner supervisor and directing the reader to additional sources for in-depth perspectives.

From My Inner Landscape: My Current Experiences in Supervision

Today, as an experienced coach and coach supervisor, I regularly engage in all forms of supervision from my inner supervisor to group supervision, knowing my work is always enhanced when I actively reflect in the company of a coach supervisor who inevitably sees that which is only dimly visible to me. Like most coaches, I have two or three areas of self that fall into the “dimly visible” category, and when a light is shined on one of these areas, my work is stronger and my development deeper. One of these areas in my work, a never-ending aspect of my development, is cultivating more heart and, in so doing, demonstrating more vulnerability. What I have come to refer to as my “be strong” story was a smart one to devise as a child, but as an adult, a parent, a coach, and a leader, it has long been evident to me that it has a downside in equal portions to the upside. It has been an area of development I have worked on most of my adult life and will likely continue to work on forever. Here’s how it showed up not long ago in a supervision session I was having with a superb coach supervisor.

I brought a situation to 1:1 supervision, a small segment of a supervision session that I knew could have gone differently. Even in the moment I was aware that more could have unfolded if I had just been a little more alert to how I might more skillfully pivot. The segment of the supervision session went like this:

The coach brought a case to our call and as he described his client and his own stance with the client I was aware in the moment that I was managing a reaction I was having, which was something like, “That sounds like a wild thing.” I focused on my judgment and reaction and worked to put them on the shelf and manage myself to simply be present in the moment. While I knew sharing my judgment would be wholly unhelpful, I was confident I missed an opportunity to explore something important in that moment. I was aware, or at least I imagined, that others in the group were also holding back a bit, as the group remained nearly silent and even when I queried others about what was happening, very little was forthcoming.

As I described this vignette to my supervisor, she made three observations and comments that threaded through our discussion:

- She wondered what might have emerged if I had consciously paused to center myself with a breath, activated my heart, and then magnified the moment.

- She wondered how I might explicitly put more space around a moment like this, sharing more of what’s happening in myself in a heartful way and wondering how it was for the other?

- Then, after we had explored both of these powerful inquiries and as we neared the end of the session, she wondered, “In your life right now, what might change for you to be just a bit more heartful with yourself?”

These were powerful observations and inquiries and all delivered with lightness and heart. She was drawing my attention to my work—cultivating more heart. This will always be a part of my work. Today, after many years of my work as a coach supervisor, I regularly ask myself, “If I had come from more heart, what might have unfolded differently?” Today, as a human being, I return to the wonderful question, “If I were to magnify an open heart in my private life, what might emerge in new ways?”

If we return to the roots of our stories and essence of our beliefs and how we develop as leaders and coaches, all that we have recounted in our own supervision and development links to honing a twice-born life—going vertical in our development, building the capacity to turn subject into object, and staying awake to the stories that could lead us to live half awake, in habit instead of in choice.

“Who You Are Is How You Coach”

Coach supervision first emerged in Western Europe and in the United Kingdom, in particular. The roots of the terminology and the practice are well documented in the field of psychology as a means of continually deepening one’s capacity. Edna Murdoch, one of the early pioneers in coach supervision emanating from the United Kingdom, often uses this wonderful phrase: Who you are is how you coach. Edna credits Aboodi Shabi as first saying this to her, but I believe she is responsible for implanting this powerful message in the work of so many of us. It’s piercing to consider the meaning of these seven words. Who you are is how you coach. It suggests that knowing who we are as coaches is a requirement if we are going to do our best work. It suggests that understanding the origins of our stories and beliefs is essential in having a perspective that is agile. It suggests that to be a great coach demands much of us, and the practice of coaching supervision adds a potent platform to cultivate our Self as Coach and our capacity to be great.

At Hudson, we established the first Coach Supervision Center in the United States in 2012, as a small group of master coaches who had been engaged in a year-long coach supervision training experience in London. Upon completion of our own supervision training experience, we began offering group supervision to leaders completing our year-long coach certification program. No matter how high the quality of a coach certification program or an academic degree program might be, the work of becoming a great coach requires practice, reflection, input, and adjustments throughout the course of a coach’s life cycle. In our Supervision Center, we have found the impact of group supervision to be especially meaningful for coaches committed to being at their best through their own development.

The Inner Supervisor in You

Admittedly, I have a bias that coaches support their own development and their best work with clients by engaging in regular supervision and at this time in this young field of coaching, we have a growing body of literature supporting this position. Today, in the field of coaching, supervision models and processes are well established and powerful sources of learning and guidance for us. While I will briefly review a few of the well-known models and approaches, my bigger goal is to broadly make linkages that will entice you, the coach, to explore these sources in more depth as you develop your own inner supervisor. Structured supervision will always play an important role in our work as coaches, yet equally important is our commitment to developing practices to examine our work in new ways with new eyes and to continually engage in a disciplined reflective process that turns up the heat on our work.

Our Inner Supervisor Supports our Vertical Development

When we ask bigger questions about our work, when we step back to deeply pause and notice that which is on the fringes of our work, when we pay attention to what scared us and what left us feeling uneasy, we are taking a deeper dive. When we enlarge our awareness of what is happening inside us as coach—our breath, pace, tensions, and how we hold ourselves—and draw our attention to the dynamics happening between coach and client, we are focused on our vertical development. The emphasis is much less on “what should I do?” with supervisees coming to seek answers and direction. This is not a space for the supervisor to play the role of “if I were you,” which is so tempting for many of us. Rather, this space is a mighty challenge to go deeper instead of riding the surface of our favorite “tells”!

On the surface, it seems satisfying to seek the answers from others and search for tools that might help, and while these are useful and have a place in our work, the supervision space and the inner supervisor work encourages and provides an opportunity to step back and reflect on what happened in a particular session or a series of sessions, what didn’t happen, what was happening for the coach, what was missed, what was aroused by the work, what was attended to, and what was ignored. These explorations lead to the cultivation of new territory and depths for the coach; these explorations expand our work. Imagine asking yourself some of the following questions after each of your coaching sessions.

Bigger Questions to Cultivate Your Inner Supervisor and Deepen Your Work

As you read the list below, you will see the interplay of the Self as Coach dimensions at work as you ask yourself these questions and hone your inner supervisor:

- How did I show up for this session?

- Was I present and centered or scrambled and wobbly?

- What feelings and thoughts were present as I walked into this session with this particular client?

- Was I able to arrive with a fresh set of eyes?

- How did my client show up?

- How did our session begin?

- What were the opening words?

- What was my intention?

- What did I notice about my own inner rumblings – my biases, hopes, concerns?

- What were my client’s requests and hopes for our time together in this session?

- How might I describe the quality of our holonic energy?

- How would I describe my working alliance with my client?

- Are there any ways I might adjust my empathy—too much, too little?

- What signals occurred that gave me a sense my client feels connected?

- How was my own boundary management? Was I able to help my client see their story or circumstances instead of allowing myself to get drawn into the situation?

- Was I aware of any urge to rescue my client?

- Is there anything this client stirs in me? Is there anyone this client reminds me of?

- Are there interventions I felt particularly useful?

- Are there observations that I did not share?

- Were there times in the session when I had a sense there was something else I might do or be but couldn’t find the entry or the courage? What can I learn from this?

- Was I attuned to the broader environment of my client as we worked?

- How did our session conclude?

- What is important for me to remember and ponder before our next session?

- What are the emerging stories and stances my client lives and only sees dimly?

- Is there anything that makes me uneasy or uncomfortable in the presence of this particular client?

- What didn’t I say or do that might have proven useful in this session?

Haven and Harbor

Supervision—whether formally undertaken in group or individual work, or when cultivating your inner supervisor—is a haven and a harbor wherein a coach is able to take a step back and look at their work from a variety of angles, seeking to gain new views. This space allows a coach to deepen their capacity to use what’s in the room, create heat experiences, understand one’s own stories, question one’s beliefs, delve into one’s vertical development, and uncover new edges of development. This is the haven where a coach is able to speak the unsayable, admit the unthinkable, take risks that feel uncomfortable, safely explore, then awaken to one’s own limiting stories, seeing and sensing in new ways the dimensions of one’s Self as Coach.

Supervision is a place focused on the now rather than the space in which we talk about, theorize, or plan. The supervision experience often parallels what has unfolded in coaching as well as what has unfolded in the vignettes brought to supervision. When we are able to see parallels, new doors open for us. There are a handful of discoveries we can uncover with just a few key inquiries like the following:

- As you scan your coaching engagements, what do you notice about your approach, your habits, your go-to models and tools. Even while these approaches and tools may bring value, how might they cause you to miss something? Might your regular approaches and tools leave you overlooking small signals that might bear fruit?

- As you scan your development as a coach, where have your growth spurts come from and what have these growth spurts uncovered for you in your coaching? Could you graph the pivots or draw a picture that captures them?

- Most often, our learning comes from the tough times, the unknowns, and the ones that keep us up at night. Spend some time capturing the list of your tough times over the past year. See if, upon reflection, you are able to discern key themes that are useful.

There are helpful models and frameworks in the field of coaching that are particularly useful in traditional supervision and in cultivating one’s inner supervisor. The details of these models are readily available for any coach to explore so, for the purposes of this book, I will mention the most prominent models and seek to link them, highlighting both common ground and distinctive features.

Frameworks and Models to Grow Your Inner Supervisor

This brief review of some key frameworks and models, used in traditional supervision and helpful in growing your inner supervisor, is meant to whet your appetite and encourage you to explore in more detail. I begin with two models on reflective practices that then inform the other models in this section.

Schön’s Teachings on Reflective Practices

It’s impossible to review models of supervision that highlight reflective practices without recognizing Donald Schön’s (1987) early work on supervision in PhD coaching. In the early 1980s, he was already examining how we learn, and his explorations led him to believe that the only learning that has the capacity to deeply influence one’s behavior comes from self-discovery, stimulated by a coach’s ability to help someone learn what is important for them, rather than teach someone else what you deem essential.

Argyris and Schön’s Double Loop Learning

Chris Argyris and Donald Schön, in Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective (1978), debuted double-loop learning, which has become a widely used model for learning. The most common approach to learning was once single-loop-focused on looking at results and problem-solving to improve on those results. Double-loop learning, shown in Figure 10.1, challenged leaders to go a step well beyond fixing or improving upon a problem and, instead, asked leaders to go deeper and challenge underlying assumptions and beliefs that dictate and determine what we do.

Figure 10.1 Argyris and Schön’s Double-Loop Learning

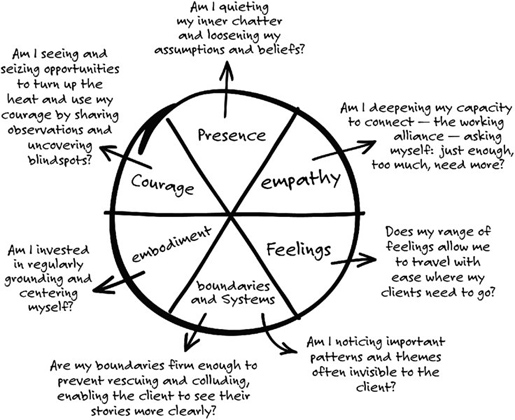

Self as Coach Model

The Self as Coach model (Figure 10.2) provides ample ground for amplifying awareness using each of the domains. Throughout this book, I have offered reflective inquiries you might use to amplify your awareness of your capacity to use self in your work.

Figure 10.2 Self as Coach: Sample Reflective Inquiries

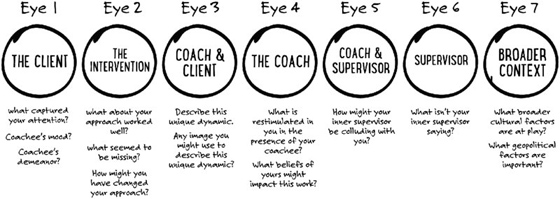

Hawkin’s Seven-Eyed Process Model

Peter Hawkins (2007) developed a thoroughly useable model for coach supervision that has deftly stood the test of time. His studies reveal that each supervisor seemed to have a consistent area of focus in their supervision work and that focus, more than any other factor, was responsible for their styles. This led to an awareness that there are several key areas of focus essential in supervision; hence, the seven-eyed process model of supervision emerged and continues to evolve into its present form for use in coaching supervision today. The current model reflects the work and collaborative thinking of Hawkins along with Smith, Schwenk, and Shohet. It also draws on the work of de Haan as it relates to the internal and relational lives of individuals.

The seven-eyed process model (Figure 10.3) includes seven foci for exploring a coaching session, including: (1) the client; (2) interventions chosen by the coach; (3) coach and client relationship; (4) the coach; (5) coach and supervisor relationship; (6) supervisor focus on one’s own process; and (7) the wider context of the engagement.

Figure 10.3 Hawkins Seven-Eyed Process Model of Supervision

Clutterbuck’s Seven Conversations

Clutterbuck (2010) created the seven conversations model shown in Figure 10.4 to draw the coach’s (and coach supervisor’s) attention to all that occurs in a coaching engagement beyond the specific dialogue during the coaching sessions. He sought to enlarge the coach’s perspective beyond what the coach did or said in the session by highlighting dialogue between and within coach and client. In so doing, he emphasized a systemic view of dialogic dynamics. He stresses that the spoken dialogue that occurs in a coaching session is highly dependent on the other conversations, the internal and contextual preparation the coach engages in prior to the session, as well the client’s internal conversations and preparation.

Figure 10.4 Clutterbuck’s Seven Conversations in Supervision

These models provide maps to guide our reflections into areas we might miss or avoid. Each map has a slightly different focus with plenty of overlapping and linked territory. Don’t land on just one; try all of these and more. Our reflective practices need to be disrupted in order that we might stay fully awake, lean into new areas of our development, and risk letting go of well-worn habits that don’t serve us as well today as they may have in the past.

Supervision as the Ethical Compass for Self as Coach

Supervision widens our view of who we are as coach and allows us to gain a clearer view of what lurks in the shadows and limits our work. To be great leadership coaches we need to be steadily and regularly immersed in our own development. Development takes time, practice, and reflection in order to create deep change at the vertical level rather than clinging to what to do and the tools to employ.