Viewed through the long retrospect of a quarter of a century, the events which preceded and accompanied the great uprising of the people in 1861 possess an almost melodramatic interest when compared with the terrible tragedies of the succeeding years of bloody strife. From the day that the result of the general election of 1860 was known, the preparation for an armed resistance to the national authority throughout the Southern states began, and for four months the government looked upon these seditious proceedings with a wonderful complacency, hardly rising above a keen curiosity as to what might be the next scene enacted. And yet these four months were nothing more nor less than active, diligent, and resolute preparations for war, absolute and predetermined measures of hostility, which should and could have been suppressed in their incipient stages, before the mass of the Southern people were dragooned into tardy acquiescence in rebellion.

The guns of Sumter, as they echoed through the land, aroused the North to the reality of the situation. From March 4 the City of Washington had been trembling over a slumbering volcano, surrounded on all sides by hostile elements, containing within its precincts a seditious horde, many of whom were life-long parasites upon the public treasury. The anxious authorities knew not what a single day or a single hour might develop. Rumors of the wildest character filled the air. Undisguised and open threats had been made that the seat of government was to be captured. In fact the national capital, with its archives, its memorials, and its treasures, was at the mercy of an invading host, had they chosen to assail it. Under these circumstances came the call of the president for seventy-five thousand men. It was only a measure of defense; even then it was fondly hoped that the dread calamity of war might be averted, notwithstanding all the seditious acts. Nevertheless the call to arms meant war, and New York City rose up as one man to assert the supremacy and the power of the government.

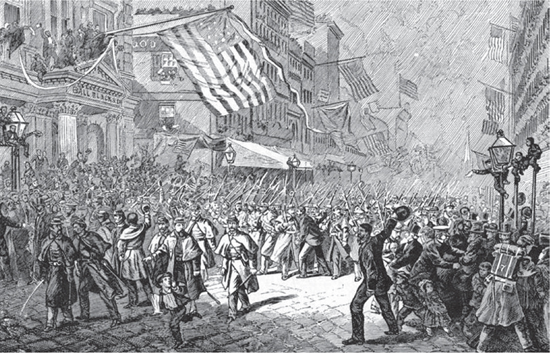

Never before was, and perhaps never again will be, witnessed such a scene as that on Union Square, on April 20, 1861. Burning words of eloquence and patriotism stirred the people to action. Sixty thousand resolute, earnest, and determined men then and there resolved to offer their all—themselves, their sons, and their sons’ sons—for the national honor and the national defense. The day before, April 19, New York had witnessed another scene only paralleled by this one. In response to the call of the president the Seventh Regiment had answered like the minutemen of the Revolution.

This truly representative body of citizen soldiery embraced within its ranks all walks, all callings of life. Merchants, lawyers, physicians, tradesmen, artisans—all were represented. In fact it would be impossible for any body of men to be more closely identified with the active business interests of the metropolis. At a moment’s notice all these interests were laid down, and exchanged for the sword and the musket. Those who witnessed the departure of the regiment will never forget it. Amid the plaudits and the tears, the blessings and the fears, of the entire populace assembled along the line of march, they moved with full ranks and steady tread. A thousand bayonets glittered in the sun, and a thousand stalwart citizens passed out from the life of the great city to meet an unknown danger, many perhaps never to return.

It was a solemn hour, and it left the homes of New York filled with sorrowful forebodings of the future. Then came the startling intelligence of the burning of the railway bridges and the destruction of the approaches to the capital. The Seventh had arrived at Philadelphia, and in consequence of obstructions to their progress by land, had taken the steamer Boston to reach Washington by sea and the Chesapeake, and all communication ceased. The mails were stopped, the telegraph wires were cut, and a terrible suspense hung like a pall over the city. Rumors came of disaster, of bloody engagements, of lack of provisions, of hunger, privation, and distress. Then promptly came forward the merchants and the bankers with open coffers. A “Union Defense Committee” was organized, and any amount of money generously pledged and freely contributed to the cause. A vessel was chartered without a moment’s delay, and loaded with provisions for the gallant Seventh. The steamer Daylight was the one selected.

Five hundred volunteers offered their services to join the regiment; very many of them were young men of independent fortunes or sons of wealthy citizens. There was only room for two hundred, who were accepted. The engineer officer of the regiment, who with a few other members had been detained on its departure, took command of the vessel and the contingent. They assembled at the armory of the Seventh on the morning of the twenty-fourth, and after a few hours’ drill, entirely new to most of them, they marched down Broadway to take the steamer with the bearing and appearance of veterans, and amid an ovation second only to that which greeted the regiment five days before. Meanwhile, the main body of the regiment had passed through the Delaware to the sea, down the coast to the mouth of the Chesapeake, and thence toward Annapolis.

The March of the Seventh New York down Broadway in New York City (Magazine of American History)

What was before them they knew not. Possibly the mob spirit that had risen uncontrolled in Baltimore and murdered the men of Massachusetts had taken possession also of Annapolis, and the landing there would be disputed. A sudden and peremptory hail, in the midst of a dense fog, from some vessel in the stream as they approached the city, seemed portentous of evil, but a nearer view revealed a United States man-of-war, and brought about a mutual surprise and relief, as neither had any knowledge of the possible presence of anything but a hostile force.

Then followed a speedy landing, and the revelation that destruction had also overtaken this route to the capital. The railway had been torn up, the cars destroyed, and Washington more then ever menaced with danger. A panic had seized the people. Women and children, and even men, were fleeing from the impending danger. The force at the command of the authorities was insignificant, compared with the number that were said to be gathering for its capture or destruction.

To overcome this fear, to meet this emergency, there was work to be done by the Seventh. Communication must be reopened and established at whatever cost, and cheerfully they undertook the task. The railway must be rebuilt, the engines repaired, weary marches were to be made, an unseen foe to be looked for at every step, and all this by men unused for the most part to manual labor and unaccustomed to privations or fatigue. Inspired by a common purpose, there was no lack of enthusiasm or of energy. In these first days of the long and bitter struggle the minds of men were not yet accustomed to the scenes of carnage that came all too soon, and the events through which these novices in war were passing were accompanied by all that sense of danger and demanded all that fortitude of character that were called forth by the more tragic events that followed.

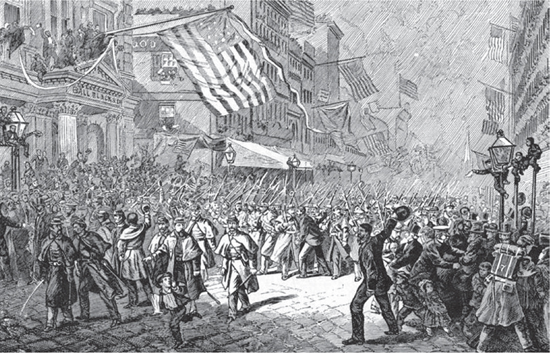

The evidences of general disaffection in the state of Maryland were too palpable not to warrant the anticipation of a night attack on the bivouac while the railway was being repaired, but the regiment was thoroughly prepared for this. At length Annapolis Junction was reached, where the train dispatched by [Lieutenant General Winfield] Scott received the regiment and hurried it to Washington. Its arrival was worth ten thousand men to the anxious loyal people of the capital, for it gave them that sense of relief and security they had not felt for weeks. Deploying into columns as soon as they left the cars the regiment marched the entire length of Pennsylvania Avenue, cheered and greeted at every step, to the White House, where they were received by the president, and then marched back to the Capitol and quartered in the [House of] Representatives.

While the route from Annapolis was thus being opened to the capital, the Daylight, with its contingent and stores passing down the bay, steamed direct for Hampton Roads. During the trip a constant drill was maintained. Arriving after dark of the second day, the lights in the lighthouses were found to have been extinguished, while the dim outline of the coast was barely discernible. Moving cautiously shoreward with the leads thrown on both sides of the vessel, the channel was found, and the steamer passed safely into the roads and anchored under the walls of Fortress Monroe, while the commander communicated with [Lieutenant Commander J. H.] Gillis of the United States steamer Seminole. Having learned that the Seventh had gone to Annapolis, as also the Eighth Massachusetts, he decided to proceed direct to Washington by the way of the Potomac. No vessel had yet made the attempt, in consequence of the rumor that batteries had been erected along the river. Commander Gillis kindly loaned two Dahlgren howitzers with an ample supply of ammunition. These were placed at the bow of the Daylight, giving her the appearance and the effectiveness of a gunboat, and thus equipped the contingent set out to open the way to Washington by the Potomac. All the buoys in the channel had been removed, and progress was necessarily slow. This afforded time to drill the artillery assignment in the use of the guns. They were beautiful pieces, great pets with the navy, having been used in the attack on the Peiho forts in China, and were inscribed with that victory.

Lieutenant Horace Porter of the Ordnance Corps of the army, afterward General Porter, had joined the Daylight at New York, there being no other way to reach Washington, to which place he had been ordered. To him was given command of the artillery, and with great diligence he qualified the gunners in their duties. Arriving off Fort Washington, opposite Mount Vernon, the vessel was brought to by a shot across her bow from the fort.

On going ashore the commander learned that the utmost consternation prevailed at Alexandria. Refugees were arriving every hour at the fort, and reported five guns in battery on the wharf to prevent any relief by the river going to Washington. The alternative of staying where they were or being blown out of existence was gravely presented to the commander of the detachment by the commanding officer of the fort. It was a responsible and trying position, but after a careful inspection of the vessel, finding that the boilers were protected by the coal bunkers, and having great confidence in the grape and canister of the howitzers as well as in the courage of the men, the commander determined that duty pointed the way to the capital. As the Daylight approached Alexandria the cannon were trailed for action, muskets were loaded, and each man stood ready for the word of command that would follow the signal of hostilities from the shore. It was a serious situation. As the vessel steamed slowly by, not a word was spoken. The insurgent sentinel who placed the wharf looked steadily at the armed ranks that faced him, but uttered no sound. The flag of disunion fluttered from the staff whence [Colonel Elmer] Ellsworth subsequently tore it down and lost his life simultaneously with that of the man who unfurled it to the breeze, and soon the town was passed, without a word or shot being exchanged. It was better so; although a different result might have hastened the issue with advantage to the government. At any rate the Potomac was opened and the Seventh New York had won another laurel.

The next day the First Rhode Island followed the Daylight in the Bienville. It was a dismal rainy Sabbath day (April 28) when the Daylight was made fast at the Washington wharf. The president and secretary of state hastened to welcome the new arrivals. They came at once to the steamer, and President Lincoln grasped the hand of every man on board, not excepting the stokers and firemen, whom he called up from their work to thank them as heartily as the rest for their courage and their presence in the hour of need. A detachment of four men held a large piece of canvas at each corner to shelter the president from the rain while the hand-shaking took place. The next morning the regimental band with an escort came down and escorted the Daylight reinforcements to the capitol, and the bivouac on the floor of the [House of] Representatives.

What a scene the capitol now presented! At the entrance, cannon loaded with grape and canister were planted. Arms were stacked in the rotunda, and sentinels guarded every avenue of approach. The whole building was one vast barracks. A bakery was improvised in the basement. Thousands of barrels of flour and other provisions filled the crypt. The marble floors resounded with the constant tread of the relief guard. Every available spot within the legislative halls, the galleries, and the committee rooms was appropriated for sleeping places, and the one great fact was now established beyond all peradventure that no flag but that of the Union could ever float over that great edifice.

The monotony of daily life, if such a life could be called monotonous, was varied in numerous ways—among other were mock sessions of Congress, with all the gravity and, perhaps, more assumption of dignity than actual representatives. The proceedings would be conducted in regular order. A speaker would rap with his gavel and the House would come to order. Members from different sections would rise to debate. Innumerable and extraordinary points of order were raised, and constituted, as in many more legitimate assemblages, the principal business of the House. It was a glorious field for the display of wit and humor, and was a never-ending source of amusement. An occasional visit from the president to their spacious quarters at the capitol was always an interesting event to the regiment. One or more cabinet officers generally accompanied him.

Every day new regiments poured into Washington, until the city became one vast camp. As soon as the equipage of the Seventh could be forwarded, a camping ground was chosen and tents pitched. The regiment then left the Capitol in charge of a permanent guard. The camp of the Seventh soon became the center of attraction. The evening parades drew large crowds to Meridan Hill. Every day witnessed marked improvements in drill and discipline, and it is safe to say that a more soldierly body of men it would be difficult to find.

The Seventh New York Quartered in the House of Representatives (Magazine of American History)

Then came the mysterious order for a midnight movement—to what point and for what purpose no one knew. Each man was supplied with forty rounds of ammunition and three days’ rations, and at 2:00 A.M., without music and with but one low word of command, the regiment left its camp and marching silently through the city crossed the Long Bridge into Virginia. Colonel Ellsworth’s forces moved at the same time down the river to Alexandria. The tragedy of Ellsworth’s death and its speedy revenge followed quickly. It was the beginning of a long and bloody conflict, the history of which will probably never be fully told; but its results will be traced for many generations to come in the higher and nobler plane of civilization that has been developed through the length and breadth of the American continent under and by its influence.

The task of the regiment did not end here. Twice again it went with equal alacrity to the front, and although as a regiment it was never brought face to face with the foe in battle, it gave more than six hundred of its brave men to most of the battles of the war, and its roll of honor is starred with the names of many heroes who poured their lifeblood freely out pro bono publico; but that first march, the echoes of whose tread reverberated through the land, was the tocsin that called the nation to arms, for it marked the deadly earnestness with which the Union was to be defended.