The Principal battles of the War of the Rebellion have been fought over again on paper so often that everyone knows or can learn as much about them as one who fought in them. For a soldier engaged in the fight can see but little [of] how the battle wages away from his immediate vicinity, and it is only from the separate accounts of the several acts of the drama, often simultaneous although far apart, that one can learn the whole story of a battle, with the various incidents, each having more or less influence upon the result.

What I saw of the First Battle of Bull Run forms the subject of this article. What I shall say will relate largely to the movements and behavior of the Second New Hampshire Regiment, to which I belonged, the only regiment from New Hampshire engaged in the battle, but a fair type of all the New Hampshire and indeed of all the New England country regiments. It is not my purpose to try to analyze the tactics and maneuvers by which we won a victory and then suffered it to be snatched from us. I shall try simply to tell a plain, unvarnished tale of what came within my own ken—the unpleasant things I saw and in which I took an unimportant part.

The first accounts of the battle produced the impression of the total rout and panic of the whole Union army. The correspondent of the London Times and other newspapermen, together with many congressmen and civilians, who had come out to see the fun and were the first terror-stricken fugitives from the vicinity of the scene of battle, drew pictures of men pale with terror throwing away their guns and equipments, cutting the traces of artillery and baggage horses, and stampeding from the enemy in close pursuit. The effect produced by these accounts has never been done away with, and today the common belief is that the whole Union army became a disorderly mob and fled from the field in uncontrollable panic. This, notwithstanding the official reports that many regiments and brigades withdrew from the field in good order, some of them ignorant that there had been anything like a panic.

The Century Magazine for May 1885 contained an article written by General [Joseph] Johnston, who commanded the Rebels in the battle, which of itself alone is a sufficient contradiction of the earlier statements. He says, “At twenty minutes before five, when the retreat of the enemy toward Centreville began, I sent orders to [Brigadier General M. L.] Bonham to march with his own and [Brigadier General James] Longstreet’s brigade by the quickest route to the turnpike and to form across it to intercept the retreat of the Federal troops. But he found so little appearance of rout in these troops as to make the execution of his instructions seem impracticable; so the two brigades returned to their camp.”

Confederate “Quaker Gun” at Manassas Junction (Forbes, Life of Sherman)

[Colonel James Ewell Brown (“Jeb”)] Stuart’s cavalry followed our column on the Sudley Springs road; and if we did have to show them our heels, they found them too well shod to venture near them. Our regiment took on to the field seven four-horse baggage wagons: we did not know any better then. Every one of the wagons, with horses and harnesses unharmed, returned safely to camp—thanks to level-headed Quartermaster Godfrey and his New Hampshire teamsters.

In the report of several Union officers are statements of their ineffectual efforts to rally troops hurrying from the field in disorder, after it was known that the day was lost. There must also have been some foundation for the civilians’ stories of panic and flight—I do not know how much foundation for them, nor can I say how many soldiers, if any, were able to overtake the London Times man and other civilians and join them in their flight. The scenes of the panic are described as being on or near the Warrenton Turnpike, some miles distant from us, and were limited in extent and duration. I can say that the Second New Hampshire Regiment, from the time it left its bivouac in the morning until after it left the field on its retreat, preserved its organization and was at all times ready to perform any duty which it was ordered to perform. The same is true of all the other regiments in [Colonel Ambrose E.] Burnside’s brigade. During the progress of the battle I saw some regiments advance under fire and withdraw in disorderly haste. I saw disorganization and disorder at other times, for which I could see no cause, and the men themselves who were in disorder appeared to be wondering what it all meant. But for myself I did not see on any part of the battlefield anything which could be properly described as a panic.

One day, just after the morning drill at our camp in Washington, we received our first order to march to a field of battle. The order contained several instructions as to details, ending with one that the surgeons should take their “amputating instruments.” I don’t think I ever read any other sentence which made me feel so uncomfortable as that did. It suggested the possible personal consequences of the expedition we were ordered on and thoughts of wooden legs and empty sleeves would obtrude on my mind. It seems odd to me now that the picture of Captain Cuttle with the iron hook fixed to his elbow should have risen to my mind, and I wondered if I could learn to use the hook as deftly as the captain did. Fortunately for me, the point of the observation did not lie in the application of it.

All fancies were soon dispelled by the actual business of preparation, and on July 16, with knapsacks packed and haversacks filled with rations, we marched cheerily over the Long Bridge into “Dixie,” and for the first time trod the “sacred soil” with hostile feet. We, with the First and Second Rhode Island and the Seventy-first New York, formed a brigade under Colonel Burnside. At night—luckily a pleasant one, barring a slight shower—we turned into a cornfield, and for the first time bivouacked in the field, lying in the soft furrows, with knapsacks and saddles for pillows; not a bad bed, although primitive in its makeup and appointments. One of the men asked the quartermaster to see that the bars were put up, so that we should not take cold.

As we proceeded the next day, we had from time to time to remove trees which had been felled across the road to obstruct our march, and we invaded two or three Rebel camps, which were hurriedly abandoned at our approach. Some of us could bear witness to the savoriness of some smoking hot dishes just served, though comments were made on the bad manners of the Rebs in not waiting to welcome us to the repast they had cooked for us. The hard streets of Fairfax Court House, upon which we slept—those of us who could—the second night made us think with regret of the soft furrows of the cornfield. As we entered the town on the heels of the retreating Rebels, we remarked a want of correctness in the flag which floated from the courthouse, and one of the men of the Second Rhode Island pulled it down and ran up one which had more stars and stripes on it.

On the night of the eighteenth we made our bivouac a short distance from Centreville, where we remained three nights. Two of New Hampshire’s most distinguished men paid us a visit, and of course we gave them our best parlor bedroom, which was the inside of a baggage wagon on the left of the regiment. In the middle of our second night here there was an alarm on the extreme left of the brigade, followed by rapid and continued firing, which raised some commotion. Soon after it began I saw, through the light of the campfires, our two guests coming at a pace which showed that they were not out for a mere stroll about the camp. They did not return to their luxurious bedroom, but spent the remainder of the night out of doors within our lines. At the beginning of the disturbance the Second New Hampshire was ordered to remain quiet and not to stir without orders. For this we scored our first compliment from the general, who commended our coolness in a night alarm. I never learned the cause of the alarm, but it was supposed to be a rather close reconnaissance by the enemy.

The Federal Army Marching to Bull Run (Forbes, Life of Sherman)

After several orders and counter orders to prepare to march, we at last received one, on Saturday night [July 20], to cook rations and to be in column at 2:00 A.M. the next morning; so the pots were set to boiling, and about midnight the boiled beef was cut up, the coffee poured into the canteens, and the brigade was promptly in column and on the road. After passing through Centreville, we were brought to a wearisome halt of two or three hours, waiting for some tardy troops in front of us to get out of the way, and the sun had risen and begun to shed uncomfortably warm rays before we resumed our march. Crossing Cub Run, we left the turnpike, turning to the right into an unused path through fields and woods.

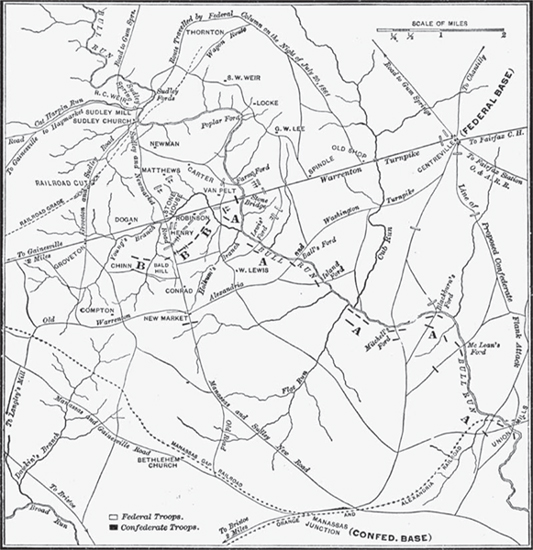

Outline Map of the Bull Run Region (Century)

I wish I could adequately describe the loveliness of this summer Sabbath morning. In the midst of war we were in peace. There was not a cloud in the sky; a gentle breeze rustled the foliage over our heads, mingling its murmurs with the soft notes of the wood-birds; the thick carpet of leaves under our feet deadened the sound of the artillery wheels and of the tramp of men. Everybody felt the influence of the scene, and the men, marching on their leafy path, spoke in subdued tones. A Rhode Island officer riding beside me quoted some lines from Wordsworth fitting the morning, which I am sorry I cannot recall. Colonel [John S.] Slocum of the Second Rhode Island rode up and joined in our talk about the peaceful aspect of nature around us. In less than an hour I saw him killed while cheering on his men. At the door of a log hovel stood a woman who so loved the “sacred soil” that she bore much of it on her person; she told us that there were enough Confederates on ahead to wipe us all out, and that her old man was one of them.

Suddenly the stillness of the morning was broken by the sound of two cannon shots, the signal that the brigade which had kept on by the turnpike had reached its position. Men ceased speaking and without orders closed their ranks, and only the sullen rumble of the artillery wheels was to be heard; the influence of our peaceful surroundings was gone, and men were reminded that the time which was to test their manhood had come. An officer from the front came galloping back and asked for Colonel [Gilman] Marston. “Tell him to have his men ready, for we shall soon meet the enemy in large force,” he shouted, and continued on his way to other regiments. The Rhode Island regiment in front of us was hurried on, and soon the sound of cannon was heard, mingled with the sharp rattle of musketry. The sergeant of the pioneer squad asked what they should do with their axes and shovels. He was told to throw them down by the roadside, and we would pick them up as we came back. We did not stop to pick them up when we returned.

Colonel Gilman Marston, Second New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry (New England Magazine)

An aide ordered us forward to support the Rhode Island batteries. We pressed forward, and as we reached the field another aide ordered us off some distance to the right on to an acclivity, where we received our baptism of fire. Here we first became acquainted with the hateful ping of bullets. One reads of the frightful crash of bursting shells and roar of cannon balls; but if anything can make the gooseflesh come upon a soldier in his first battle it is the spiteful hiss of a bullet and its dull thud as it buries itself in the ground—or in something else.

A regiment of the enemy was in front of us at rather long range. Our two flank companies were armed with rifles. After one volley, the order was given to fire by companies. One of the flank companies fired, and then the other, with such effect that the enemy withdrew to the shelter of the woods. In the language of the sporting ring, we had won the first round. It was a Georgia regiment from whom we had drawn first blood. A year afterward, at the Second Battle of Bull Run, the same regiment was halted near where lay one of our wounded men, Charles Taber of Company C. As soon as the Georgians saw the “Second N.H.V.” on his cap, they treated him with friendly solicitude, and removed him from where he was lying, exposed to dropping shot and shells, to the shelter of an embankment. They knew all about the career of our regiment and what battles it had fought in, from the First to the Second Bull Run. We were the first troops with whom they ever exchanged fire, and they manifested a very hearty goodwill toward us.

The movement to our position was a mistake, caused by the confusion of staff officers of different generals, whom we were unable to distinguish, and who had not had time to learn to distinguish regiments of different brigades.

Suddenly there appeared, as if they had sprung out of the ground, a large force of Rebels away to our left, in front of the Rhode Island regiments, and we were hurried off to meet them, moving by the flank and exposed as we passed to the fire of the Rebel force in front of us. On our way, two companies, by the mistake of another aide not on the staff of our brigade, were separated from the regiment, and it was only by the active exertions of our own officers that they were brought back again—an example of the blunders to which we inexperienced officers and men were subjected. We passed some caissons; just before we reached them a cannon shot took off a hind leg of each of the two wheel horses. I had already seen men wounded and killed, but no such pitiful sight to me as that of those poor horses.

We took our position near the Rhode Island batteries, and soon one who was fond of fighting must have passed a pleasant half hour. Burnside’s brigade alone was opposed to the whole Rebel force on that part of the field. Volley after volley was given and received through the thick smoke, and it seemed as if the air was filled with bullets, cannonballs, and bursting shells. There was a moment’s cessation of firing on our left; a body of men bearing what we thought was the Union flag were advancing toward the First Rhode Island. There were cries of “Don’t fire on our own men,” when a murderous volley was poured into the Rhode Islanders. The fire was returned and the Rebels fled. My recollections of the details of this part of our fighting are not very distinct. We, with other regiments of the brigade, advanced, climbed over a fence, pushed through an open field, and drove the enemy into the woods beyond; then we were halted; a brigade on our right came up and kept on driving the enemy; and [Colonel William T.] Sherman with his brigade came up on the field quite a distance to our left, and the enemy was driven further and further back, across Warrenton Turnpike, through the fields and still further back into the woods beyond.

Colonel Marston was severely wounded in the shoulder and carried to the rear just as the fighting began. A soldier in Company A had one of the strange escapes from what seemed certain destruction, which sometimes happen in battle. A shell struck between his feet and exploded; he seemed to me to rise a musket length in the air without any will or effort of his own, and I expected to see him fall dead, but he alighted on his feet with an oath, which showed that he was very much alive and in no fear of immediate judgment. He walked back to Washington that night.

As we stood in line with our brigade, the firing ceased, and there came a stillness over the field which seemed uncanny; we looked at each other as men might do who had been in some great disaster and escaped unharmed. Was the battle ended and the victory won? A riderless horse came out of the woods opposite us; a sleek, glossy creature, looking as if he was some lady’s pet. He came whinnying toward us at a gentle canter, until we could see spots of blood on his saddle. Just as he reached us a cannon shot from the woods broke his leg, and a soldier of the Seventy-first New York shot him dead. It seems a trivial incident, but it attracted the attention of the whole brigade, and to me it is one of the most vivid recollections of the day.

A cheer came from away off to the right, and was taken up by us and rolled along to the extreme left. [Brigadier General Irvin] McDowell rode down our front announcing that we had won a glorious victory. One of our men near me said, pointing to some columns of dust over the trees to the south of us and moving toward us, “It seems to me, Colonel, that if we have whipped them, that dust ought to be moving the other way,” and soon firing began again on our right. In reply to a question by Colonel Burnside, he was answered that the Second New Hampshire was ready to obey any order it received, and we were ordered off to the right, to take a position abandoned by another regiment and to report to [Brigadier General Samuel P.] Heintzelman. Just as we were about to start, Colonel Marston came up mounted, with his shoulder bandaged, and said, “Now we New Hampshire boys will have a chance to show what stuff we are made of.” He was received with cheers, and accompanied us until repeated entreaties not to take the risk of aggravating his wound induced him to return; but he left the inspiration of his presence with us.

Irvin McDowell as a Major General of Volunteers (Century)

On the way to our new position our two left companies, B (Captain, afterward Major General [Simon G.] Griffin) and I (Captain, afterward Colonel [Edward L.] Bailey) had a short but sharp exchange of compliments with a Rebel regiment. It required a very peremptory order to bring them back to their place in column. While we were halting a moment, one of the men offered me some water from his canteen, which he had just filled at a pool nearby. Upon my declining it, he raised the canteen to his own lips, throwing his head back, when a cannonball nearly severed his head from his body. Such a sight at home would have made me sick and faint with horror; but now, after only two or three hours of familiarity with battle scenes, my principal feeling was astonishment that a cannonball could make such a clean, knifelike cut, so quickly does one adjust one’s self to one’s environment.

Soon after we reached the position which we were ordered to take, and had reported to General Heintzelman that we were waiting his orders, we received an order to take and hold a position further to the front, and advanced to the line indicated. We were fired upon here and suffered some casualties. The enemy in front of us were hidden by the irregularities of the ground and by a clump of trees, with nothing to indicate their presence except the puffs of smoke from their places of shelter. As our orders were only to take the position and hold it, we withdrew just behind the crest of ground we were on and waited for further orders, or for the enemy to attack us.

A Federal Charge at First Bull Run (Century)

We saw two of our batteries take a position on the further side of the Warrenton road, where they did great execution on the Rebel artillery and infantry. A Rebel regiment came out of the woods to the right on the flank of the batteries and moved steadily toward them. The guns of the batteries were moved and aimed at the advancing regiment. “Why don’t they fire? Why don’t they fire?” we exclaimed. When at close range the regiment poured a volley into the batteries, and it seemed as if every man and every horse went down, and in fact every cannoneer, with many other men, and most of the horses fell. The Rebels captured the guns, and they were retaken by our men. Three times they were taken and retaken, sometimes by a single regiment on one side or the other, and sometimes by two or three regiments advancing together, but apparently without concert, until at last our men withdrew, taking three of the pieces with them. It was afterward known that the reason why the batteries did not fire on the advancing regiment was that the commanding officer was told that they were our men. This mistake was one of the principal causes of our defeat. Had the batteries fired, they would have annihilated the Rebel regiment and resumed their destructive fire on the Rebel line.

After this the fighting continued in desultory and spasmodic advances and repulses by one side or the other—the general effect being adverse to us—and we saw many men leaving the field in disorder, but not apparently in fear or with any great hurrying. At last an aide came with an order for us to retire to our brigade. When the order was given to march “common-time,” we retired slowly and in our usual order, although many of us doubtless felt rather queer—I know that I did when I gave the order. Lieutenant Colonel Rice, then a private in Company A, has since told me that when he heard the order “common-time,” he felt as if mud turtles were crawling up and down his back; another man said that his knapsack had felt pretty heavy, but when he turned he wished it was made of cast iron; another said that he didn’t see why old “Double Quick,” as he irreverently called the commanding officer, couldn’t put us through as he used to on drill, but he thought if the officers, who were nearest the enemy, could stand it he could.

I relate these things to show the feeling which pervaded us; that is, we wanted to get away from the foe now advancing in considerable force, but with never a thought of moving faster than ordered—“common time.” We halted once, ordered arms, and rested several minutes. Soon after we had resumed our retreat, some of our cavalry came up between us and the enemy. The commanding officer told us to hurry up or we should be cut off. He was thanked for his warning. We closed up our ranks, but did not “hurry up.” The cavalryman again told us in a somewhat more peremptory manner to hurry on or he would not stay to protect us. He was told to go to and protect himself, and that we could take care of ourselves. I looked around and saw a body of Rebel cavalry perhaps a quarter of a mile away, coming toward us at a slow trot, which did not look to my inexperienced eye much like a dash to cut us off; and moreover I was willing that they should try it, although I think now that we might have fared badly if they had charged on us. They did not attempt to molest us. Rice of Company A, whom I mentioned a moment since, was shot through his lung, the bullet passing entirely through his body. He was laid behind a building nearby and reported killed by the men who bore him there. We heard no more of him until he came into camp the following November, an exchanged prisoner from Richmond. He had been kindly cared for by a family living near the field until removed by Rebel surgeons. A few years ago Colonel Rice visited his hosts, who were people of narrow means, and he wished to make them some return for their kindness. They refused his offer for themselves, but said their church was very poor and in debt $200, which the society was struggling to reduce, and they would be grateful for a dollar or two for that object. When Mr. Rice reached home he related this to the editor of the Springfield Republican, who published the story with a request for contributions. Before nightfall $246 were received. As Mr. Rice’s host was on his way to a church meeting, sadly pondering his society’s embarrassment, he stopped at the post office, where he found a letter from Rice with a draft for $246, with which he entered the meeting. One can picture to one’s self the effect. The bloody chasm between that society and the North was completely obliterated.

We soon reached the field where were our brigade and a large number of men of other brigades without organization or order. There were many hundred men scattered over the ground, some standing in groups, some lying down, some wandering about, searching for bullets and other mementos of the battle. There was no appearance of fear or even uneasiness; they mostly seemed to be dazed and wondering what we were to do next. There were also the nuclei of many regiments. Colonel Burnside proposed that our regiments should rally and resume their places in the brigade. The proposal was received with applause and carried out with spirit, and soon there were, I think, at least two thousand men in column, all of them willing and expecting to resume fighting, and many of them eager to do so, when Colonel Burnside, who had been to see General McDowell, came back and said that the order was to retreat. Strange as it may seem, I then for the first time realized that the Union army was beaten. I could hardly believe that we were ordered to finally abandon the field. Weary and dispirited, we retraced the path by which we had come with such different feelings in the morning. Soon after we entered the woods there was a cry that the Black Horse Cavalry was upon us, which caused much disorder; and after that there was little regard paid to regimental formations, and companies became more or less mingled. But the alarm was momentary, and the column moved on at a leisurely pace, and those near me were calmly discussing the events of the day.

A squad of men joined our regiment, having with them as a prisoner the lieutenant colonel of a Mississippi regiment, captured by the Fifth Minnesota. As we rode along side by side, I had a long conversation with him. He was a Rebel because his state was, and personally did not approve of secession. He was taken to Washington and held there till exchanged.

We kept on until we were near the bridge over Cub Run. The enemy had placed a battery near there, and were sweeping the turnpike and bridge, which last was covered with the wreck of wagons, among which lay dead men and horses. Lieutenant Platt of Company C asked permission to take some men and capture the battery. As we were in the immediate presence of Colonel Burnside, the permission could not be given. We learned long afterward from Rebel prisoners who manned the battery, that a dozen men could easily have taken it.

Our way was completely obstructed. The banks of the run were steep and rough, and we must reach the other side. All formation was broken, and everyone, with or without orders, scrambled across as he could. As Colonel Burnside, with myself and two or three other mounted officers, rode up the hill after crossing the run, the battery fired three times at us, bringing down upon us a shower of twigs and leaves from the branches above us. Several times during the day I had wished I was at home in New Hampshire, but never more fervently than when riding along that knoll. Some of our regiment joined our colors after crossing, and we returned to the bivouac we had left in the morning, where others of the regiment came, singly and in groups, for an hour or two afterward. We had been marching and fighting eighteen hours, with scarcity of food and water, and were completely overcome by fatigue and exhaustion. We threw ourselves on the ground like overworked oxen, and many of us were instantly sound asleep.

The Black Horse Cavalry (Hearst’s Magazine)

At about 10:00 P.M. Colonel Burnside, who was just across the road, was asked if it were safe to send Colonel Marston to Washington without a guard. The answer was, “Your regiment must be in column in fifteen minutes to march to Washington.” It required much rough but kindly meant treatment to arouse the men. The teams were harnessed, the camp kettles and utensils were thrown into the wagons, and we took our places in column. The last sight I saw, as I rode out from the bivouac after the regiment, was Surgeon Hubbard and Assistant Surgeon Sullivan amputating, by the light of a campfire and a tallow candle, the arm of Private Derby of Company A, afterward lieutenant, who was wounded at Cub Run while gallantly volunteering to act as one of the color guard. This was the first serious operation in the war on a New Hampshire soldier wounded in battle.

One can fancy what the march that night was to us. On Monday forenoon, July 22, we marched through the city of Washington to our old camp, and the Bull Run campaign was ended. Our regiment had passed through its first war ordeal; and if it had done nothing to win honor, it had also done nothing to bring discredit on itself or on the state which it represented. The men untried in battle, their officers oppressed with a consciousness of their great responsibilities and of their lack of military experience, the regiment was six hours on the field, where was the hardest fighting of the day, taking an active part in much of it. It was more than once under fire which it could not return, the most trying position for any soldier, veteran or recruit. There were examples of disorder all around it, yet through it all the regiment bore itself steadily and bravely on the battlefield from the very beginning of the fight to the very end of it. Although this is not the place to speak of the subsequent career of the regiment, I take leave to say, before dismissing the subject—I can speak without self-praise, for before it was in another battle [Brigadier General Joseph] Hooker put me in command of the Twenty-sixth Pennsylvania Regiment, and I never rejoined the old Second—that as in the Battle of Bull Run, so through the whole war, from the beginning to the end of it, in Hooker’s first brigade, on many battlefields, in victory and defeat, it always bore itself steadily and bravely and won a high reputation as a fighting regiment.

General Sherman is reported to have said that the Battle of Bull Run was one of the best planned and worst fought of the war. It was not fought on any plan at all; it was a number of fights by separate regiments and brigades, without united effort or mutual support, led by their respective commanders without concert in the various movements. The day was one of mistakes and blunders on the Union side from the very beginning. The tardiness of [Brigadier General Daniel] Tyler’s division in the early morning, in leaving its bivouac and getting out of the way, caused the long delay of [Colonel David] Hunter’s division, prevented the well-planned surprise, and gave the Rebels time to prepare to meet the attack on their left flank. The misdirection of Heintzelman’s division, and the delay in placing [Colonel Andrew] Porter’s brigade, left Burnside’s brigade to bear the brunt of the first hour’s fighting alone. The advance of the batteries of [Captains Charles] Griffin and [J. B.] Ricketts, before assurance of adequate support, was a fatal mistake, and last of all the failure to bring up the reserves and hold them at Stone Bridge left the retreating columns to face about and protect their rear as best they could.

A man, whom I did not then know, was moving about our part of the field, a civilian, although I have heard that he afterward volunteered, looking from under the broad brim of his straw hat upon the various maneuvers, like some country farmer on an old-time-militia muster field. Strolling from one point to another with his hands in his pockets, I noticed more than once that he did not seem to mind whether he was under fire or not. A noticeable man anywhere; when I met him some days afterward I recognized him at once. He told me that he was on the field the whole day, and that if he had been in command of the Union troops he “would have licked the Rebels out of their boots with one hand tied behind him”; a presumptuous thing for a civilian to say, but I believed then he would have done what he said he would, and I believe so now. The man’s name was Joseph Hooker.

I do not wish to say anything unkind or disrespectful of General McDowell, nor could anything which I might say affect the honorable record which he made as a brave soldier and good general; but at the First Battle of Bull Run he failed to keep his forces well in hand, and to make movements and combinations, not contemplated in his plan of battle, which unforeseen exigencies of the combat made necessary in order to secure and complete the success we won in the first part of the day. Officers and men felt the want of a commander-in-chief present to oversee the field of battle and to control and direct his various forces in the shifting vicissitudes of the fight. The want of such a presence was manifest on our part of the field from our first encounter with the enemy until we quit the field. Brigades and regiments appeared to be fighting each “upon its own hook,” as the commander of a brigade said to me.

A battle is a game in which, after it is won and lost, the men cannot be set up again to play a back game; but we may for a moment permit ourselves to think of about how the game might have been played out from the situation as it was at noon on that day. After driving the enemy from the field, we should not have been left standing an hour or two idly gazing on the field from which we had driven them, while [Generals Joseph E.] Johnston and [Pierre G. T.] Beauregard reformed their lines and brought up their supports. Our forces, reunited and kept well in hand, flushed with the success already won, would not have given the Rebels time to catch their breath, but would have kept them on the run on which we had started them and sent them whirling down to and through Manassas, as [Major General Philip H.] Sheridan afterward sent them “whirling through Winchester.” They had already made good progress in that direction, for at noon there was as great a panic among the Rebel troops as was said to be among our troops at 4:00 P.M. Mr. [Jefferson] Davis, coming from Richmond, met a stream of fugitives reaching from the field to Manassas, bringing reports of the disastrous rout of their army. The difference between them and us was that they did not have, as we did, a crowd of terrified civilians to lead them in flight and magnify the effects of it, nor a London newspaperman to publish to the world exaggerated and highly colored accounts of its character and extent. They did have an active and able chief—two chiefs—who rallied their beaten troops and led them in person on to the field again. We did not have a chief who, riding to the front of battle, planted his colors there and called on his disordered brigades and regiments to rally around them. But if there was one panic, there were two; when they jeer about the one on our side, we can answer back tu quo que.

There has been much dispute as to the numbers engaged, each side claiming that the other had the larger number. I think, judging from the official reports of both sides, there were about twenty thousand on each side actually engaged on the field. According to these reports, our loss in killed and wounded was about five hundred less than that of the Rebels; about one thousand four hundred prisoners were taken to Richmond, making our total loss about nine hundred more than that of the Rebels. We also lost twenty-five guns.

The battle derives its importance from the time and circumstances. It was the first conflict which tried the mettle of northern hardihood and southern chivalry, and each side learned there to respect the fighting qualities of the other. Many people, and I am one of them, think it fortunate that we lost the battle. What would have happened if we had won no one can tell; but it is probable that some adjustment would have been patched up, and it would have devolved on a younger generation to renew the “irreconcilable conflict” and fight it out. It was better as it was.