Major Robert P. Barry was born in New York City on March 30, 1839. His father was Samuel F. Barry, originally of Boston, and his mother was Martha Lewis Peabody, originally from Salem, Massachusetts. Robert Peabody Barry was the youngest son. After education in private preparatory schools, he attended Columbia College. When he first entered the institution it was located at Church Street, between Murray and Barclay, but during the time that he was there the grounds were sold and Park Place was cut through. The college then moved to Madison Avenue and Forty-ninth Street.

While at college he became a member of the Delta Psi fraternity, and as a delegate attended a convention held at Raleigh, North Carolina. In his memoir he says, “Here I met members from many states, but what impressed me was the tone of our Southern members. All expressed a sort of dislike for and an enmity to the Union. It struck me as very strange and most unusual, for up to this time I had never heard anything like it.”

After the convention he visited friends in South Carolina, and his memoir continues, “It was a very enjoyable visit to me, but I noticed here also the strange views of my host when any remarks were made about the country, how the government was regarded, not as theirs, but as a sort of hostile one.” The memoir further continues,

I was at an evening entertainment given by a young friend—a Southern girl—the night the news arrived of the attack on Fort Sumter. Boys crying “Extra” ran along Fifth Avenue; some one went out and bought one and, bringing it into the parlor, read aloud the news of the attack upon the fort by the Southerners. An instantaneous chill fell upon the guests and the party soon broke up. The next day troops were being mustered to go to Washington, and on the Seventh Regiment, New York militia, being called, I volunteered. I hurried home and told my parents and, without my uniform, joined the regiment and left with it for Washington. We mustered at the Tompkins Market, near Eighth Street and Bowery, and marched from there through Broadway to the Jersey City ferry. The houses all along the route, also the pavements, were filled with an excited and cheering crowd.

He served as a private in the ranks of the Seventh Regiment during its historic expedition to Washington in 1861, but upon its return to New York he sought a commission in the Regular army, and through the influence of Hamilton Fish and other influential friends of his family he secured a personal interview with Secretary [of War Simon] Cameron, and received an appointment as captain in the newly organized Sixteenth Regiment of Infantry of the Regular army. He was first detailed upon recruiting duty in a mining territory on Lake Superior, but his regiment was subsequently attached to the Army of the Cumberland and sent to the front. They took the field at Nashville, and it was shortly after this that his regiment participated in the battle of Shiloh, which is described in the accompanying letter.

After the battle of Murfreesboro, in which he was wounded, he was placed in an ambulance to be sent to the hospital at Nashville. A part of the wagon train, including his ambulance, was captured by Confederate cavalry, but he and other officers were paroled and ultimately reached Nashville. When he was wounded his sword dropped on the battlefield, where it was subsequently found and, having his name engraved upon the hilt, was sent to the regimental headquarters. While in the hospital at Nashville, his general called upon him and brought him the sword which had been thus recovered from the battlefield. Had it not been for this incident it would undoubtedly have been taken from him at the time of his capture, but through this caprice of fortune it remains a treasured relic in his family today.

After his convalescence he was duly exchanged and returned to the front, where he served throughout the Atlanta campaign under Sherman, at times, owing to the scarcity of officers, he being himself in command of the regiment. During his active service in the war he bore the rank of captain, but subsequently received his commission with the brevet rank of major for gallantry in action.

Subsequently to the war Major Barry went into business in the South as a cotton merchant, and in the early eighties retired from business and settled upon a farm of approximately five hundred acres which he purchased near Warrenton, Virginia. Here in October 1912, he passed away.

The letter referred to runs as follows:

[April 14, 1862]

My Dear Mother, My last letter was written at our camp at Mount Pleasant. The next morning we were up at four o’clock, and that day made a most fatiguing march. At 10:00 :A.M. we came to a river, where we rested half an hour and were told to fill our canteens, as there was no water for ten miles. We crossed the river and commenced a most dreadful march. The sun was scorching—the road, a light clay, was a continual dense cloud of fine, white dust, blinding to the eyes and choking to breathe. Often I had to put my handkerchief to my face for breath. No shade during our rests—oh, it was horrible! When we came to the next water it was barely possible to keep the men from breaking ranks in a body and rushing to cool their parched throats. At 7:00 :P.M. we came to our camping ground on the banks of a lovely stream. Here officers and men bathed, then a good drink of whiskey and a short nap restored me. My men, though, commenced to fail and I had to give some frequent drinks of whiskey from my flask, to keep them up. For myself, though, I never drink till after the march. The next day at 6:00 :A.M. we were again on the march, and this day saw many houses of Union people, who greeted us with waving flags (a very rare sight down here). One flag at Waynesboro had on it “Peace and Union.” We made but fourteen miles this day, the roads were so bad. We had a beautiful place to camp and, this being Saturday, were told we would rest over until Monday, but soon we received orders to have reveille at 4:00 :A.M. Sunday, which indicated a long march; so at 4:00 A.M. we rose. Mother, let me tell you that the old saw, “Early to bed and early to rise,” etc., is an immense humbug—there is no truth in it. I have tried it now for some time, and from experience can say that he who can lie abed and does not do so is a big fool. This day (Sunday) the roads were still worse than the day previous—they sometimes became so narrow and so steep, running as they did through deep gorges, that it was difficult for us to march. How our heavy wagons could pass seemed a question; but they did, and indeed it must be a very, very bad and impassable road that will stop army wagons.

About 9:00 A.M. we first heard the indistinct sound of cannon, and then they commenced to force us. It was broiling hot. I stuffed my cap with grass, but still could not prevent a racking headache. Still we pushed on—up young mountains, down valleys, till twelve, when we were marched in an open field and given an hour for rest. Here word was received from [Major General Don Carlos] Buell to leave our teams and press on. The teams of the whole division were left here, covering hundreds of acres. Oh, how hot it was! I took off my vest and left it in the wagon, keeping only my blouse and pants. Unhappy act! How I have suffered for that temporary relief! Now commenced our race. When the road went straight we followed the road; when the road turned for hills and streams we left the road, broke down fences, and took short cuts; up hills, down hills, over fields, through streams; nothing stopped us. Our general had had orders evidently to bring us there. It seemed as though, too, the sun would kill us. Still on we went—the booming of artillery growing more distinct as we pushed on. There was evidently a battle raging and we were wanted. The song and jest were no more heard. We were too tired to talk, too solemn to jest. Once we stopped on a hill where was a rude church building; in this the officers of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth took shelter from the sun. I threw myself down and offered a mental prayer to the Almighty for strength for the coming trial.

Soon the bugle sounded, the men fell in, and again was that mad race taken up and kept up until 7:00 P.M., when we were within two miles of Savannah; here we were given two hours for refreshment. Our refreshment consisted in lying down on the river bank and regaling our palates with hard bread and water. I tried to sleep, but could not. I was too cold (all the nights are cold) and too tired, so I sat on a log and talked. It was rumored that the Union had got the worst of it, but no one knew anything definite, so I concluded not to bother my head about the numerous stories that were circulating.

Between 9:00 and 10:00 P.M. the bugle sounded, and we commenced our march to Savannah. It was slow work—the road was filled with troops and the transportation was limited to take them over the river. It was 12:30 A.M. when we were in the boat. The scene was impressive, the streets filled with artillery and infantry, all moving toward one point. No word was spoken. Only the masses of men drawn up in close column could be seen, with the occasional reflection of starlight on the brass cannon. Then, too, the buildings filled with the wounded and the lights that lit up their rooms! To see there thousands of men and these scores of batteries and to hear no loud talking—no shouting—only to be aware that the dusky mass kept moving steadily toward the river. To see all this, mother dear, and then to know that many of us would never see another night, was in a measure stunning to the senses. Our halts were frequent, and the men, who were wearied out from marching from 4:00 A.M., would throw themselves down in the dust and go to sleep. Lieutenant [Edward L.] Mitchell and I sat down on our gauntlets, the only protection we had. At midnight we got on board and were stowed like herrings. When my men were placed I threw myself down on the deck and went to sleep. But it was too cold to sleep—and then first I repented leaving off any of my clothes. Soon it began to rain. No, not to rain, to pour. I managed to get shelter along with Mitchell in a sort of stateroom of the officers of the boat, and had just got to sleep on the floor when some brute woke us and insisted on our leaving. At first I felt tempted to cut the scoundrel down, but, learning where I could get shelter, I left, first damning him up and down, telling him he was a dirty sneak, only fit to be a nigger, and every other provoking thing I could think of. I felt mad and wolfish, for I had learned on the boat of our defeat Sunday, and it seemed so cursed mean to drive out in the rain the men who came to risk their lives to retrieve the defeat. Just before we left the boat this fellow happened to pass me, there being at the time a number of officers about. “Well, you mean sniveling puppy, do you want to turn me out of here?” said I, and I commenced to abuse him in true Billingsgate style. He had nothing to say. At 4:00 A.M. we were up and breakfasting on hard bread and water, left the boat, and scrambled up the bank.

Marching through the Rain at Pittsburg Landing (Young Volunteer)

And now for the battle. Sunday morning [April 6, 1862] the Rebels attacked [Major General Ulysses S.] Grant’s forces, taking them completely by surprise, owing to the criminal carelessness in posting and attending to the watchfulness of our pickets. Our camp extended out seven miles. They drove our men back slowly but steadily all day until there was no place for them to go but into the river. There was no generalship and apparently no attempt to deploy and to make use of our large army. Each regiment fought for itself and when whipped fell back till all men crowded together like sheep. We were whipped as fairly and as badly whipped as we could be. Our trains were captured, our artillery captured, our men a mere mob of regiments without order or plan. And let me tell you that an army without its organization of divisions and brigades is as unmanageable as a regiment would be without companies. And so at evening Sunday Grant’s army was a beaten army, and only the interposition of the Almighty saved it. Why the Rebels did not complete their victory and drive Grant into the river seems inexplicable. Some say they feared the gunboats. The country is all hills and woods, and the gunboats, of which there were but two, could do but little. As it was, only the mercy of God and that only can account for our safety. During the night some hasty entrenchments of barrels covered with dirt were thrown up and all our troops lay down with anxious hearts for the following day. But night brought Buell and safety. [Brigadier Generals William] Nelson’s and [Thomas L.] Crittenden’s and part of [Alexander McD.] McCook’s divisions were thrown across the river, and those divisions, comprising 25,000 men, did most of the fighting Monday.

The fight was opened by Nelson on the left at 4:00 A.M., and soon was taken up along the whole line. But you have learned of the general fight—how the left was pressed back by the Rebels, then driven back again and finally from the field. So I will tell you only about our brigade and companies, which are spoken of in terms of praise by the whole army.

We scrambled up the bank from the steamer through thousands of our brave volunteers who were guarding the river bank. Do you know that whole regiments were skulking on the banks behind the stones and could not be forced into the fight either Sunday or Monday? Scores were drowned in their attempts to get on the boats, and it was only when the guns of the gunboats were trained on them that they could be induced to leave the banks. One whole brigade refused to enter the fight. Damn them! I would have trained the artillery on them and sent them to the fight. Well, we scrambled up the steep bank and formed the battalion by companies at a time; then we were marched a short distance into the woods. After that the Fifteenth, Sixteenth, and Nineteenth [U.S. Infantry] were formed in double column at half distance and marched out toward the enemy. All day Sunday we had been on the march, all we had for food was hard bread, and now to get up at 4:00 A.M. Monday, breakfast on hard bread, and go into a battle, was rough. I felt weak and scared, and I fear I looked pale. I almost wished I was home. The cannonading was now lively as we pushed on through the woods. Soon we came to a camp, and here and there and everywhere were the mangled bodies of men lying in the positions. in which they had fallen, some writhing still of wounds, who had lain all night in the drenching rain on the muddy ground. Oh, my God! thought I, this is too horrible! We halted and I sat down on a box and covered my face with my hands. Mother, at that moment I wished I was home. I looked up. All around were the mangled, dead, and dying bodies of men and horses. Then I thought, this will not do. I have had too many fair hands shake goodbye with mine, so, Bob, be up! We were ordered to take position more to the left. No voice sounded more cheerily than mine as I repeated the orders, though God knows I was sick at heart and weak in the knees.

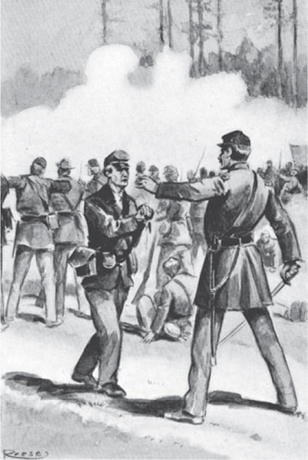

We took position in the woods on our right. The enemy now seemed to be gaining ground on the left and the shell and round shot kept hustling through the trees. We were ordered to advance, so, deploying in line of battle, we moved forward through the thick brush. General Buell, riding along, ordered us back, so we gave ground. Now the shot and shell seemed to increase. Our men were halted and told to rest. I sat on a log and pressed my stomach to overcome the weakness I felt. I was not scared, but painfully nervous and frightened. The sound of a ball or shell startled me. I offered frequent mental prayers to the Almighty that I might obtain mercy should I be taken away. Our skirmishers were now ordered forward, and soon we heard a shot, and then, as they came running back, the order was given, “The enemy are on us! Ready! fire!” I jumped up; there, indistinctly through the brush, their gray line could be seen, and then we received a fearful volley. My company swung around as it were upon a hinge, the right standing fast. That minute worked in me a change. The poor, weakened, faint-hearted Captain Barry was another man. I never thought of danger. I never thought of anything. My sword flew out of its scabbard. I grasped my pistol with my left hand. “Get back to your places,” I shouted; “back or die!” At the same time I pressed them with my blade and thrust the muzzle of my pistol in their faces. “Back, back! Meet your fate like men, not like cowards! Is this Company F?”

Driving Troops Back into Line (Young Volunteer)

Another minute and my company was in line and were returning a heavy fire. I moved up and down the line, cheering and encouraging my men, now speaking personally, now to all. I had several narrow escapes. I was struck on my scabbard twice, so that now both belt and scabbard are ruined. Another ball grazed my ear and struck a tree just behind me, causing a singing and pain in my ear that lasted all day. One of my men told me when he saw it, “that he thought his captain was gone.” The fire was furious and in ten minutes we had driven them back. Then the bugle sounded “Forward,” and we advanced, occupying the ground from which we had driven the enemy. And here, while we remained at “in place, rest,” I saw what made me wolfish. Those loud-mouthed valorous ones of the volunteers commenced to slink away. I stopped several that passed through my company and, by a free use of cocking and presenting my Colt, induced some of them to halt and take post with my company. One fellow came limping along and passed through my company. “Halt there!” said I. He paid no attention. “Halt!” repeated I, and the click of my Colt induced him to turn round. “What’s the matter with you ?” “I’m wounded in the foot.” “Where?” He showed a muddy but uninjured boot. “You lie, you infernal coward. You eat and sleep at the country’s expense and then run when you are wanted to fight.”

“I ain’t afraid, but—“

“Well, then, take your place in my company and fight with my men, and I’ll shoot you if you run.” I made another man a minute later, but the enemy now appeared, so I forgot all about them. They skedaddled, though, at the first fire, and probably commenced to rob the dead. We again caught it hot and heavy, though this time the men kept their places, and I at one time went in front and dressed them to the right, they coming up as coolly as on battalion drill.

As for myself, after the first fire I felt none of the weak-kneedness, but took all things as coolly as though I had lived all my life in battles. Here it was that Mitchell fell. The wings of the battalion were crowding the center, so I stepped back and informed Captain [Edwin F.] Townsend, who was in command, that they must give way to the left, as my company were in some places three deep. He said, “You run and tell Captain [Robert E. A.] Crofton to face his company (the left one) to the left and so give you more room.” Mr. Mitchell cried out, “I’ll do it!” and started out. He had just finished giving the order when a bullet struck him on the right temple, passing completely through his head. He slightly lifted his right hand, fell, and expired instantly. I did not learn of his death till ten minutes afterwards, and almost cried when I heard of it. During the hottest part of this fight Slidell, who has been absent sick for a month, came up. The plucky fellow had hunted us up and now joined us. The determined stand of our men under a very heavy fire of musketry and artillery was too much for the graybacks. They gave way. And now we did the prettiest thing imaginable. They seemed to waver and Captain Townsend cried, “Change front, forward, on first company.” By Jove, mother, we went through the evolution under a hot fire as prettily as we would on drill, only when I right turned my company and dressed them to the right I felt ticklish. The men did the movement well, and I learned that we were complimented by those high in command who saw it.

Then came the order, “Fix bayonets and double-quick, march.” The Rebels, who were within one hundred yards at the time, at this gave way, and so we came in possession of a battery that had been playing on us all the morning. Such a sight as it was! The men lay around in scores, most shot through the head. The horses of the battery were piled all together, kicking, struggling, and dying. Early in the morning I would have fainted at this sight; now I coolly examined the dead to see where they were hit and what the effect of our balls hitting a man was. Our cartridges were now nearly exhausted, so we sent back a detail for more. Meanwhile we rested by lying on the red, bloody ground with the shell and grape showering around us. While so resting, a sergeant of G Company had his head taken off by a cannon ball. But they could not let us rest. The Regulars were wanted, so we were again pushed forward, and met and repulsed the enemy a third time during this action. Captain [Patrick T.] Keyes and Lieutenants [Edward] Haight and [John] Power and myself were all standing around a sapling, talking. Keyes was leaning his right shoulder against it, his face to the rear; I with my face to the front, was leaning on the other side. A ball struck Keyes, breaking his right arm. The sapling being but six inches through, this I consider my fourth narrow escape that day.

For the third time we drove the enemy back, and then up came our cartridges, and just in time, for we had but very few left per man. The cartridge boxes we filled up, and, seeing this done, I threw myself down and went to sleep. You read of Napoleon sleeping on the battlefield. Why, anyone can do it! Many of us, all wearied out, with nothing to eat for a day and a half but hard bread, and used up with our exertions—many of us fell asleep with the balls rattling about us like hail. In fact, you seem to forget or not to notice this hail of bullets. As for shells, though we had our fair share of them, they amount to little. They generally burst in the air over your heads and not half a dozen of our men were wounded by them. We rested for half an hour or so, and then the bugle sounded again the advance. “Oh, curse it, ain’t these Rebels ever going to give in?” I said as I rose wearily for what proved our last fight. We were lying at this time on the edge of the wood; in front stretched a plain of about two hundred acres. Across this we marched under heavy fire and were halted close to the woods in which lay the Rebels, who were pouring in a heavy fire. [Colonel August] Willich’s celebrated German regiment was ordered out at the same time with us. He went ahead of us in double column at half distance on his center, intending to deploy, but when he got under this fire he stopped, shuddered, and then that vast mass of men gave way and ran over our poor little battalion. We seemed swallowed up, but when they passed, our men struggled again to their places and we were one again. But we were so thrown out that we had to fall back twenty paces and reform on first company. Willich’s men rallied about one hundred paces in our rear and then did splendidly. And now we stood the most awful fire I had ever conceived. It seems it was the last stand of the Rebels on our right and they had at that moment ten thousand men opposed to our brigade and Willich’s regiment. Oh, it was awful! The air seemed laden with nothing but the rushing of balls and the shrieking of bullets. Grape and canister tore the ground all around, trees were torn to pieces. Some birds flew up but lit on a shrub and lay cowered. The whole field slowly became enveloped in a dense cloud of smoke and only the flash of the cannon could be seen. The roar was such that no voice could be heard. The bravest cowered there. Still there was no flinching, but, though the men dropped like leaves, still we held our ground.

The Regulars under Fire at Shiloh (Young Volunteer)

Slowly the cloud of smoke lightened and by their slackened fire we knew the enemy was giving way. “Fix bayonets! By company right wheel! Double-quick, march!” and moving on in columns of companies we drove the Rebels from our part of the field. We chased them one-quarter mile, when we halted, formed line, stacked arms, and threw ourselves on the ground and rested. Oh, mother, how tired I was, now the excitement of the action was over. I got some liquor, which set me up. The dead and wounded lay in piles. I gave water to some poor wounded men, and then sought some food in an abandoned camp near us. Pickled pigs’ feet, almonds, and cigars rewarded me. Battles always bring rain, and now it looked threatening. I saw lying in the mud what appeared to be a piece of rubber. I went there and found it to be a fine poncho or piece of light India-rubber cloth with a hole in the middle through which you pass your head and then tie it at the neck. This has proved most valuable. We had to bivouac that night and it rained very heavily. My poncho kept me dry, although I could get no sleep. Think of that, mother! I dared not lie down on the wet ground, yet I could not stand. Finally I propped myself against a tree and thus got some forgetfulness but no refreshment.

The next night and the next and the next, all that week in fact, it has rained day and night. It has been impossible until today, Monday, to get up our baggage, so we have had to go to what shelter we could and live all the time on bacon, hard bread, and coffee. Last night my valise arrived. Oh, how acceptable those candies were! I would not have sold them for $10,000. My shoes are all I could ask and the medicines in the nick of time, for I was giving way, as the surgeons have no medicines and those who are taken sick, if they cannot get well in the rain and open air by themselves, must die. One of my men died on our march the evening we arrived at Savannah. He died in the ambulance.

Our battalion suffered heavily. We carried into action about 250 men. We left 6 killed, 51 wounded; about twenty-five per cent., or one in four. Now we were under about as heavy fire as any troops in the field. We were pushed into action four times and lost 60 in round numbers. But none of our men ran.

When you see accounts of a regiment being cut to pieces, it is volunteer talk and means some killed and lots who ran away. Remember that for the future, mother.