When [Major General William T.] Sherman reported that Columbia was either burned by [Lieutenant General Wade] Hampton or by accident, caused by the burning of cotton in the streets by the citizens, he presented the people of the North so-called facts; but over forty thousand eyewitnesses of the scene—one half of them his own soldiers—knew the facts to be very different indeed. As a witness of what took place on that fearful night, and with most of the scenes as vividly before me as if they had occurred but yesterday, I propose to give an account of it as it occurred. It was known about February 10, 1865, that Sherman’s army had passed across the Charleston and Savannah Railroad toward Branchville, a point equidistant from Charleston, Augusta, and Columbia, being sixty to sixty-five miles from each. Opinion was divided as to its probable route from there. It was not believed that it would pass through Columbia until about Wednesday, February 15, and even then it was generally believed that it would not cross the Congaree River, but proceed up Broad River. On Thursday, however, considerable skirmishing took place between the advance of the army and a few cavalry under [Major General Mathew C.] Butler, between Congaree Creek and old Gramby Point, three to five miles below Columbia. A few companies of cavalry composed the entire Confederate force at or near Columbia, not sufficient to oppose the approach of the large army of Sherman. At this time I have no records or reports by which I could give the relative strength of the parties, but it was generally believed that Sherman had sixty thousand men, that one division had gone farther west, not far from Augusta, and that over forty thousand men were in the two divisions marching on Columbia. About twenty thousand, as well as I could estimate, crossed Saluda and Broad rivers and entered Columbia; another division, equally large, passed up Broad River, crossing thirty or forty miles above.

It should be noted that Columbia is situated on the east bank of the Congaree River, which is formed by the junction of Saluda and Broad rivers, which unite just above the corporate limits of the city. As I stated, it became evident on Thursday that the army would enter Columbia, and as there were no troops to defend it steps were at once taken to remove government stores and such things of value as were possible. There were usually three banks located at Columbia, but on account of its being looked on as peculiarity safe from attack all of the banks of Charleston, and I believe all of those of the interior, with the exception, perhaps of one, had removed to the city, making either fourteen or fifteen (I do not remember which) then in the place. Most of these banks, in addition to their ordinary assets, were crowded with immense special deposits in the way of boxes of silver plate, valuable papers, title deeds, bonds, etcetera, belonging to their customers and friends, many of whom were refugees from their homes and had entrusted their all to the banks for safekeeping. This fact will account for the immense losses that occurred from the fire and the pillage that preceded it, as these deposits were entirely too bulky to be removed at the last moment, when horses or vehicles of any kind could not be had at any price. On Thursday the railroad trains were moving everything that could be put on them—the Charlotte and Greenville roads sending off trains as fast as they could be loaded. The South Carolina, or Charleston, road had been cut below Columbia by the advance of Sherman, and was of no service in assisting in the exodus. The Confederate Treasury Department, large amounts of military stores and ammunition, and commissary stores were removed. In addition to the railroads every horse, mule, and ox was made available in removing families and valuables; but even then transportation was so limited that the banks were only able to remove their money and their books, leaving hundreds of tons of valuable deposits still in their vaults.

Late on Thursday night I was with General [Pierre G. T.] Beauregard, at his quarters at the United States Hotel, and found all arrangements complete for the evacuation of the city early on Friday morning. In accordance with orders received, General Beauregard turned over the command of the department to General Hampton, whose whole command, if I am not mistaken, did not exceed eight hundred men. Captain Witherspoon, chief commissary, gave me the keys of the different Confederate storehouses and requested me to open them the first thing on Friday morning and distribute the stores among the citizens. While engaged at this, about daylight on Friday morning, a terrible explosion was heard, which was afterward found to have occurred in the depot of the South Carolina Railroad, from some unknown cause, killing several persons who were in the building at the time. Soon after this General Sherman opened fire on the city from a battery that he erected in the night on a commanding hill just above the Congaree bridge, one mile west of the capitol. This fire on the city was begun without any notice and when no defense was intended or possible. Fortunately, no casualties occurred from it. Five shots struck the west wing of the capitol, two of them breaking and shattering the pilasters and cornice around one of the windows. A few shots also struck and passed through the old statehouse, a wooden building. A piece of shell struck the residence of my father, on Plum Street, and another piece fell into a buggy passing—the last vehicle, I believe, to leave the city—fortunately without injuring its occupant. One shot passed through the house of Captain Matthews, on Arsenal Hill, shattering a large looking-glass while a young lady was standing before it. During Thursday night a picket guard, stationed at the long bridge over the Congaree, set fire to it against orders, and it was entirely destroyed. That prevented Sherman from entering the city directly, but he passed up, crossed Saluda River near Saluda factory—after firing it—then crossed Broad River, three miles above Columbia on a pontoon bridge. I find myself giving details somewhat foreign to the subject of the burning, but even at the risk of being tedious I find it necessary.

As soon as it was known that Sherman or a part of his army had crossed the river, the mayor, Dr. Goodwyn, and two or three of the aldermen, among whom, I believe, were Mr. John McKenzie, John Stork, and O. Z. Bates, who are still residents of Columbia, went out to meet them. Dr. Goodwyn informed General Sherman that the city was in no condition to make any defense and that he had come out for the purpose of making a formal surrender of it. After some conversation General Sherman said, “Mr. Mayor, you can say to your people that they have nothing to be afraid of; that they are as safe as if there were not a Yankee within a thousand miles of the city.” After this assurance the mayor returned to the city. This occurred about 10:00 A.M., Friday, February 17. About 11:00 A.M. the army entered the city, marching down Main or Richardson Street. On reaching the courthouse and market the troops seemed to be all simultaneously disbanded and released from any restraint. The streets were soon all crowded with soldiers, but at first all seemed quiet and well disposed. About 1:00 P.M. an alarm of fire was given, and the fire bells rung. The writer hurried to the place of alarm and found that about sixty bales of cotton had been rolled into the center of Richardson street, in front of the store of O. Z. Bates, and was on fire. As I approached it I found a few men (citizens) had run out the Independent Engine from the house, near the market, not over one hundred yards from the burning cotton, and began playing on the fire. They soon extinguished it and continued playing on the smoking bales until all sign of fire was over. Not less than one thousand Federal soldiers were on the sidewalk and street looking on, but took no part at the fire until just as it was about all controlled, when a drunken soldier took his musket and plunged the bayonet into the hose pipe. Instantly a number of others joined in and with their bayonets soon cut the entire hose to pieces. The men working the engine remonstrated, but with no avail. They then ran the engine back into the engine house. Fortunately the fire was all over before this destruction of the hose, or the town might have been fired from it. Before 2:00 P.M. all sign of the fire was over.

During the afternoon thirty bales of cotton, moved out into the street from his stable by Mr. J. H. Kinard, at the corner of Plain street, was burned; also, a few bales in Cottontown, not far from Mr. R. O’Neale’s. These fires, however, were small affairs, and had no more to do with the burning of the city than they had with that of Chicago. About 3:00 P.M., large columns of smoke were seen east of the city, two to five miles off, which turned out to be the residences of General Hampton, Dr. Wallace, George A. Trenholm, the cotton and card mill of the writer, and the houses of a number of other parties. About 2:00 to 3:00 P.M. the soldiers began breaking into the stores and banks, and here the plunder and destruction of valuable property was beyond description. Thousands of boxes of valuables were stored in the bank vaults. I was passing the Bank of Charleston and the Commercial Bank of Columbia and found a squad of about fifty soldiers breaking them open and loading themselves with silver to the extent of their ability to carry. While looking on at this scene, a young man of Columbia came up with a Federal uniform coat on and with a large three-bushel bag, which he held open on the pavement as the soldiers came out with their loads. One of them told him to hold his bag open, mistaking him for one of his own comrades. Our disguised friend did so readily, and his bag was soon filled with all he could carry. After the evacuation this gentleman turned over to me, as the mayor of the city, this very silver, which I had the pleasure of restoring to the daughter of the former owner (James I. Petigru), Mrs. King, afterward Mrs. C. C. Bowen.

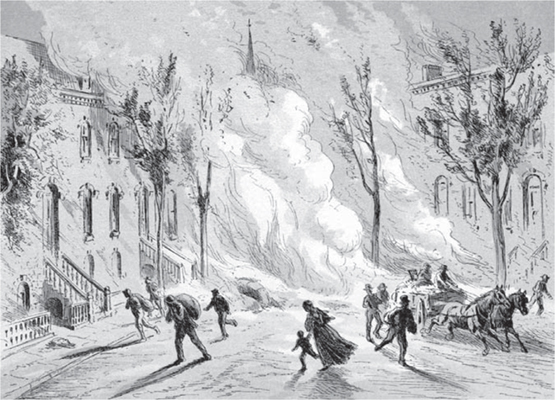

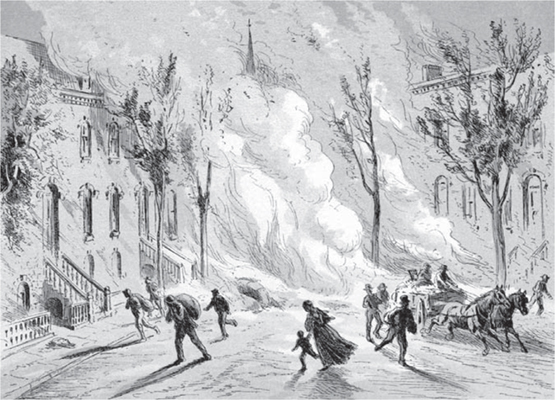

Every store in the city was sacked, as were the banks, but I knew of no serious attacks on residences that were occupied, except those in the outskirts of the city. The soldiers were generally civil and pleasant spoken, but there was a marked air of absence from all restraint and control, and the soldiers evidently knew that it was a general holiday and that they were able to do as they pleased. About 7:00 P.M. signal rockets were thrown up from three several points, all in the northwest part of the city, in what was known as Cottontown. Very soon it was known what the signal rockets meant. The city was fired in several places at the same time. Just then a high wind sprung up, blowing from the northwest. This sent the flames with irresistible violence, sweeping all before it. The city was laid off in squares of four acres each, with streets one hundred feet wide. All of the stores were on one long street—Richardson or Main Street, as it was called. This street was closely built up for about one and a half miles. The buildings on the other streets were not so close, as most of the residences had large gardens and yards attached. Frequently the distance from one house to the next was too great for the flames to lap over and ignite the next; but, alas, that mattered not—thousands of willing hands were ready to destroy what the elements were about to spare. Soldiers were seen on every side with every appliance for aiding the conflagration. Some had buckets of kerosene or turpentine, or other inflammable materials, and wherever a house was about to escape the fury of the burning storm it was immediately fired and made to share the general fate. With the exception of one small cottage house, occupied by Mr. Huchett of Charleston, at the head of Main Street, not a building was left on that street; everything on it was burned for one and a half miles and in a belt from a quarter to a half mile wide. Eighty-four squares, containing three hundred and thirty-six acres, and thirteen hundred houses were destroyed.

The fire continued throughout the night, the streets being crowded all the time with soldiers, but no officers were to be seen. I did see General Sherman riding leisurely through the streets smoking a cigar, but he gave no orders and seemed to take little interest in what was going on. No one could witness the scene without the firm conviction that the burning of the city was a pre-arranged affair, or else that the soldiers were given to understand that they had free license to do as they pleased and that there would be no restraint over them. I spent almost the entire night in the streets and witnessed many houses fired by the soldiers, and I never saw (nor did I ever see anyone who did) a single instance in which any assistance was rendered by the soldiers to save property from the flames. It was a most fearful night—sublime and grand in its awfulness. The illumination was more brilliant than I am able to describe. It seemed that the most minute things could be seen with wonderful distinctness at inconceivable distances. Not only the glare of the flames, but the millions of sparks and cinders that filled the air all helped to make an illumination that far surpassed the brightness of day. I am satisfied that, looking from the upper part of my house, I saw not less than eight hundred to one thousand men engaged in probing the ground with their bayonets or iron ramrods, searching for buried treasures. In all directions it seemed equally bright. The storm of fire—I can call it nothing else—raged with unabated fury until daylight or a little later, when my attention was drawn to a number of cavalry, in squads of three or four together, galloping though the streets sounding their bugles and calling on the soldiers to fall into ranks. This was the first sign of any attempt at discipline or the issuing of any orders to the rank and file. I understood immediately that the worst was over, and so it was. The wind was still blowing severely, but I knew that, if unaided, the flames would soon die out.

Columbia in Flames (Forbes, Life of Sherman)

At that time the track of fire was just in the rear of my own dwelling and approaching it so rapidly that all who were with me had abandoned it, and I had prepared to leave also, when I noticed the orders for falling into ranks. So satisfied was I that we were near the end that I returned to my house, and with the aid of a few of my servants succeeded in smothering the flames that were just starting in one of the outhouses, and saved the whole. In less than thirty minutes after the orders were given every straggler was in ranks and the destruction virtually over. Nowhere was the discipline of Sherman’s army more conspicuous than in the quick, prompt, and immediate recognition of their orders to stop from any further destruction of the city. It seemed like magic. All was as quiet and orderly as if the men were on dress parade where, but a moment before, it seemed as if to ruin and destroy was the only thing thought of. The ordinary population of Columbia did not exceed ten thousand, but owing to the large number of refugees from the coast there was at the time of the fire not less than twenty thousand persons, and of those not over five hundred men. I should have stated that General Hampton moved out with the few cavalry he had just as the Federal troops were entering the city. On Saturday morning squads of men were detailed for the destruction of what public property and buildings had escaped the night before. The gun works were then destroyed, the powder factory and several other public buildings. None were burned, but they were knocked to pieces or blown up.

While this destruction was going on the mayor, Dr. Goodwyn, came to me and said that he was completely broken down with fatigue and excitement, and that he was utterly unable to attend to anything, and that he had come to get me to act in his place. Finding this to be the wish of the citizens generally, I consented and immediately proceeded to take steps to meet the difficulties we were in. The situation was serious. The usual population of the city was more than doubled by the refugees and visitors who were there, and these, too, almost entirely helpless women and children; thirteen hundred houses [were] destroyed, which, in numbers, was perhaps one half of the city, but which from the location and character was really more than three-fourths of it. The city was greatly crowded before; now it would be impossible to find shelter for one-tenth of the homeless. The railroads were destroyed (that was done as soon as the city was occupied), there were no horses or conveyances of any kind to transport the people to a place of shelter, and every store and shop in the city destroyed, without a single exception. The entire stock of provisions on hand would scarcely support the people two days; in fact, there were no provisions at all, save the little in private families, and few of these had sufficient for more than two or three days. The country for miles around the city had been so thoroughly cleaned up that nothing whatever could be got from that quarter. The prospect of material aid from General Sherman did not seem very bright. I thought that we had little to expect from one who, if he did not deliberately destroy the city by positive orders, did most certainly allow it to be done without making the slightest attempt or effort to save it. I would here repeat, in the strongest language possible, that during the whole of that terrible night not a single instance was known of a United States officer or soldier making an effort to stop the conflagration. I was glad to find, however, that I was mistaken. On Sunday I received a notification from the provost marshal, I think, that the chief commissary had been ordered by General Sherman to turn over five hundred head of cattle for the use of the citizens. This was all that saved us from actual starvation—the cattle, owing to their peculiar condition (as I will explain hereafter) being equivalent to more than double that number of ordinary beef cattle.

Among the incidents that passed under my own observation were some that it would not be out of place here to relate. Some things occurred that, notwithstanding the fearful condition of things, had their ludicrous side. As soon as the city was occupied on Friday guards were detailed and stationed at a number of the most prominent houses, I suppose with a view of giving their occupants a sort of feeling of guaranteed security. At the corner opposite my house lived a widow lady, Mrs. Herbamont; she had considerable silver plate and a lot of choice old wine that was quite valuable. She gave me her silver to try and save for her, which I did by throwing it down my well; but her wine she had buried in her garden, and felt quite secure of it. As soon as a guard was sent to her house she said to him: “Now, my good man, keep a good lookout and do not let any soldiers rob me. I have over a hundred bottles of fine old sherry wine buried under that fig tree in the garden, and you keep a good lookout for me and I will give you a bottle of it before you go.” The consequence was just what might have been expected. The guard immediately hailed a squad from the street and piloting them to the fig tree unearthed the bottles, drank a few to the health and prosperity of Mrs. Herbamont, took off what they could carry and broke up the remainder.

Dr. Templeton, a prominent physician of the city, was walking in the street just after the destruction of his house, when he was accosted politely by a soldier and asked what time of night it was. Pulling out his watch to look, the soldier jerked it from him and walked off. Dr. Templeton coolly said, “Hold on, my good fellow, here is the key; it is not a bit of use to me without the watch.” The soldier said, “All right, pass it along.” The doctor had not gone fifty yards before he was asked the time by another soldier. “Ah, my friend,” said he, “you are just a little too late; one of your comrades was ahead of you.”

I have mentioned the large number of soldiers who were engaged in probing the ground all over the city hunting for valuables that were buried. Immense quantities of silver, jewelry, money, and other valuables were buried for safety, but the skill exhibited by the soldiers in finding it was truly wonderful. Bayonets and iron ramrods were used to probe the ground in all directions, and many a treasure was found and appropriated that its owner had thought safe and secure. A Mr. Mordecai, of Charleston, a refugee, who had been about a year in Columbia, had an old darkey that he loved to brag about as the only honest Negro he had ever known. He would trust Peter with everything he had in the world. He had a large quantity of old family plate (silver), so he buried it in his cellar—he and old Peter—not even letting his wife or children know where it was. As soon as the army marched into the city old Peter met the head of the column at the corner near his master’s house, and calling four or five soldiers to go with him, marched straight to the cellar and showed them where to dig up the silver. In telling about it afterward Mr. Mordecai seemed to be as much hurt by his being deceived by old Peter as he was by the loss of the silver.

On the morning after the fire I was passing the house of Dr. O. M. Cohen, a well-known druggist of Charleston, when I saw his grandchild, a little girl of four or five years of age, playing before his door with a small pet lapdog. Two soldiers were passing, when one of them, for nothing but innate devilment, took the butt of his musket and knocked out the brains of the little dog. The child began to cry piteously, when the other soldier, who was a kind-hearted man, stopped and began to pet the little child, and taking out his knife he went to work with an old cigar box that was lying near and soon had a neat little coffin constructed and the child interested in the contemplated funeral. Just as he was about to begin to dig a grave to put the dog in under a large rose bush in the front garden, Dr. Cohen came out greatly excited and did all in his power to induce the soldier to dig the grave elsewhere, but all to no purpose. Fortunately, however, the interment was completed without the discovery of the doctor’s silver, which it seems he had buried under the same bush, but luckily on the other side. Few were as fortunate.

In passing where had been the house of Mr. James K. Fridey, I saw two soldiers just taking up a large bag from a hole where it had been buried; they took from it a large ice cream churn filled with silver, which Mr. Fridey had endeavored to save in that way. I immediately walked up to the soldiers and told them that it belonged to a gentleman whose house was burned with all he had, and for God’s sake to spare his silver. They asked me what I would give them for it. I had one $20 gold piece, all the money I owned of the kind. I took it out (at some risk) and offered them that, which they agreed to take for the silver if I would throw in a fine pocket knife which they saw I had. This I agreed to with the condition that they would take the churn, bag and contents to my house—which was quite near—as otherwise I might never have saved it. This they did in good faith, and a few days after I had the satisfaction of giving Mr. Fridey a welcome surprise, as he had thought his silver had departed forever. About the time the soldiers entered the city an old colored woman, the nurse of my children, came to me and said, “If you got any money, gib it to me; dem Yankees neber git it den.” With the exception of the aforementioned gold piece, I had but $30 in species, and that in silver, so I gave that to old Aunt Hannah, more to please her than from any other idea. On Monday morning, just after the evacuation of the city, old Hannah came to me with the silver, in high glee, but looking very haggard and worn. Some of my other servants told me that the old woman had not had a moment’s rest while the Yankees were in the city; that she put the silver in her bed and that she stood guard over it day and night, and had broken the head of one soldier with a pair of tongs, who undertook to enter her room, and that he would have killed her had his comrades not interfered—thinking it a good joke, her attack on him. When last in Columbia, twelve months ago, I met old Hannah and heard her lecture on “dem good ole times.”

Early on Saturday morning, Mr. Jacob Lyons, the president of the gas company, came to me with the information that he had just been told that the gasworks, which had not been burned the night of the fire were to be blown up, and urged me to see General Sherman try and save them. I at once went to the house where General Sherman was quartered, but was refused admittance. I think, however, one of his staff advised us to see [Major General Oliver O.] Howard. So I went to him and urged him to give me an order for the protection of the gas works. General Howard was very polite, but gave me little encouragement. Finally, he promised me to see General Sherman himself on the subject, but confessed that my request would be hardly granted. He was very pleasant, and told me that, though what public buildings were left would be destroyed, that he would have no hesitation in sparing anything that would conduce to the actual necessities of the people; that a flourmill or gristmill might be saved. I immediately urged him to give me an order for the protection of the two mills that I thought of—one that of Dr. Geiger and the other of Fred W. Green; that latter, however, had already been burned, but I succeeded in saving the venerable old establishment of Dr. Geiger, known in the early days of Columbia as Young’s mill. About two hours after I left General Howard the gas works was destroyed.

Late on Sunday night Dr. Goodwyn informed me that the cattle promised us would be turned over early the next morning, and I got my brother, Dr. R. W. Gibbes, to go to the commissary early in the morning and attend to having them delivered in the enclosure of the South Carolina College, that being the only place where they could be kept together, as there were twenty acres there enclosed by a brick wall. Knowing that when the army left there would likely be stragglers and plunderers in the rear who would treat us worse than the army did, I thought I would apply to Sherman for a few arms for our protection. I was, however, again unable to see him, so I tried my old friend General Howard again. Never shall I forget the astonished look he gave me when I explained that I wanted arms. However, I urged it so strongly on him that he at last gave me an order for one hundred muskets. I do not remember at this time on whom the order was, but I found it necessary to take it to [Major General Francis P.] Blair. He was much surprised, but endorsed the order, however, to give me a lot of worthless and broken guns, scarcely one of which could be used. Nothing having been said about ammunition General Blair did not care to furnish that, but finally gave me ten rounds or one thousand cartridges, which, perhaps, did not fit over a half-dozen of the guns. These old muskets, however, did faithful service in guarding our city, and perhaps some of them are still in the city guardhouse.

About 6:00 A.M. on Monday morning a rumor got out that General Hampton had attacked the advance of Sherman’s army at Killian’s Mills, ten miles north of Columbia. That caused the hurried departure of the main body earlier than was intended, and no doubt was the reason of many doomed establishments being spared. As soon as the army departed, which was by 8:00 A.M., my brother came and informed me that he had five hundred and sixty head of cattle in the college enclosure, but that they were nothing but the refuse and broken-down portion, such as were not able to be driven any further; that no food could be procured for them, not even water, as the water works were destroyed and it was impossible to drive them to the river. A meeting of some of the citizens was held and it was decided to butcher the cattle as fast as it could be done. One hundred barrels of salt was stored in the basement of the capitol. This embraced everything in the way of supplies that could be relied on to feed twenty thousand people. Twenty or thirty volunteers at once proceeded to butcher the cattle, and even killing them as rapidly as possible, one hundred and sixty of the number died before they could be killed. During the privation of the war we had all got pretty well used to poor and tough beef, but I venture to say that such a lot of beef cattle as were given us by General Sherman were never seen together before. An old shed at the corner of Plain and Market streets, that had escaped the flames, was turned into a market or ration house, and for weeks that was the grand gathering place for the rich and poor. Here rations of tough beef and salt were given out. Those who were able to pay paid; those who could not were supplied gratuitously; but all were allowanced, and that to what was barely sufficient to feed their families, everyone having to testify as to the number of mouths he had to fill.

What at first seemed to be a great misfortune—the character of the meat—actually turned out to be a great blessing. Had it been good, fat meat, it would have been, comparatively, a drop in the bucket toward supplying our necessities, but, fortunately, its quality compensated for its quantity, and I am certain that the survivors of that time will always preserve a lively recollection of the tough, blue sinews that, like India rubber, the more you chewed it the larger it got. It was the most satisfying meat I ever saw—a little went a long way. Even with this wonderful beef and its enduring qualities it could not last 20,000 people long. I might here mention a fact, strictly true, that several hundred persons lived for fully two weeks after the evacuation solely and entirely on the loose corn picked up from the ground when the horses of the Yankee army were fed, and that, too, in a sprouting condition, the heavy rains having rotted it. Much privation and suffering ensued, and much more would had it not been for the noble conduct of Augusta, as soon as our condition was known. The citizens of Augusta loaded six wagons with bacon, meal, and flour and sent them over to us—making a present not only of the supplies but also of the mules and wagons. This was a godsend to us. We found one section of country, Fort Motte, about forty miles from us, where some corn could be had, so for weeks these wagons were run backward and forward, hauling from that neighborhood. The crowd at Columbia in the meantime scattered as rapidly as possible, many going to Augusta, Newberry, and other neighboring towns—walking being the only means of transportation. Some few ladies and children got to ride occasionally in wagons. It was, however, fully three months before permanent relief was obtained from our troubles.

The mother superior of the convent had formerly educated General Sherman’s daughter, and it seems that she managed to hold some communication with him when he was in Savannah, and it was understood in Columbia that she had been informed by him that if he did enter Columbia that she had nothing to fear, that she would be protected. In consequence of this a number of persons went to the convent for safety and others sent their valuables there. The convent was burned early on Friday night. On Saturday morning the mother superior went to Sherman complaining, when he told her to choose any house in the place that had escaped and he would donate it to her. She at once moved to the large mansion of [Brigadier General John S.] Preston, where [Major General John A.] Logan had his quarters. General Sherman, as I afterward learned, actually executed titles to the property and gave them to her. She afterward surrendered them with the property to General Preston. This incident was the means of saving that handsome edifice—now the residence of W. E. Dodge—as it would have been destroyed, as I was told by General Logan, who also told me that it should be blown up and that he only wished he had its owner there to hang him.

Early in the evening of Friday a Mrs. Boozer, who was living in a house belonging to me adjoining the Baptist Church, came to me in great excitement and told me the city was to be burned. I told her no, that she need not be alarmed, and mentioned what General Sherman had told Dr. Goodwyn. She said no, that she knew it would be burned. Her husband was a physician and at one time had charge of the hospital where some of the Federal officers (prisoners) had been located. Mrs. Boozer had shown kindness to some of them by furnishing them delicacies, etcetera, and as soon as the army entered Columbia two officers who had formerly been there as prisoners and had been recipients of her kindness hunted her up and privately informed her of the intention to fire the city. Even with this assurance I did not believe it, relying on the word of General Sherman. These two officers, however, returned to Mrs. Boozer when the fire began and remained with her till the house was destroyed and assisted her to move her young children to the asylum as a place of safety. This incident I mention to show that the destruction of Columbia was certainly pre-arranged. Mrs. Boozer is still living in Columbia and may be able to give the names of the officers alluded to.

On Friday night I went to the residence of my father, Dr. R. W. Gibbes Sr. I found that his house, a large fire-proof one, had escaped, the fire having passed it; but on my entering it I found fifteen or twenty soldiers engaged in piling up furniture in the drawing room and were using the lace curtains to fire it from the gaslights. Every effort to induce them to desist was unavailing. A young man of an Iowa regiment had been placed at the house as a guard that morning. He had accidentally fallen down the stone steps in front of the house and sprained his ankle. My father had bandaged it up for him and gave him some soothing lotion that relieved his pain, and lent him a pair of crutches that had been left in the house by my brother, Captain Gibbes, who had been wounded not long before. This guard was apparently very grateful for the kindness shown him, and certainly did beg and urge his comrades not to burn the house; but they were not to be stayed, so he then urged my father to try and save some of his valuables. This he was urging when I entered the house. I suggested to my father to try and save a portion of his collection of coin. He had one of the largest private collections perhaps in the world of old and ancient coin, consisting of several thousand specimens of gold, silver, and copper. I got the cover of the piano and we emptied the gold and silver coin on that, and made a large bundle of it and, at the suggestion of the guard, tied it around his neck as he stood by on his crutches. The copper coin was too heavy and bulky to try to move, so we abandoned them. By this time the house had been fired from the furniture piled up in the drawing room. So my father and I each took some articles of value in our hands and followed the guard, who hobbled off into the street on his crutches, with the bag of coin around his neck. He vanished among the crowd of soldiers that filled the street, and made such good time that neither he or the coin have been since seen. Not less than one hundred and fifty ladies and children collected at my house during the night of the fire. As their residences were destroyed they came to my house for shelter. Suddenly one of the young ladies, the daughter of J. Daniel Pope, remembered that in the hurry of leaving their burning house they had forgotten to bring off their silver and jewelry that had been hidden in a moss mattress in one of the upper rooms. It seemed a forlorn hope, but I determined to try and save it, the house not being very far distant. I hurried there and got into the house, which was burning rapidly; but in company with Summer, a faithful Negro, who stuck to me, we got the mattress, but finding the stairway about to fall we cut the ticking open and took out what was in it, barely escaping before the house fell in. I afterward found that every article had been saved except one old watch.

There was one incident that I will mention, as it showed the forethought of a sharp women who, in the time of trouble, looked ahead. There was a family of the name of Feaster living in a house just in the rear of the courthouse. Mr. Feaster was a very worthy, clever man, employed in the Confederate commissary storehouses, but he was principally known as the fourth husband of a quite noted woman, whom he married as Mrs. Boozer, formerly Mrs. Burton, formerly Mrs. Somebody Else—an English woman by birth. Mrs. Feaster had a daughter who had been adopted by her third husband, who had provided handsomely for her on condition that she took his name. So she was known as Miss Mary Boozer, and was considered one of the most beautiful girls ever seen in the state. The family were in but moderate circumstances, having lived very extravagantly. Mrs. Feaster was known as a very smart woman, not overscrupulous. While the city was on fire and the house she occupied was burning, General Sherman passed by. She immediately made herself known to him as a Union woman and one who had done a great deal to assist Federal prisoners, and aided some to escape. She called his attention not only to her house, then burning, but showed him a large storehouse at the opposite corner, then burning, which she told him was her husband’s, and that it had been filled with flour, bacon, and tobacco—the truth being it was a government storehouse in which her husband was employed.

On Monday, when the army moved out, she managed to get General Sherman to furnish her with two horses, which she hitched to her carriage, an old round-bodied affair, familiar to all the old residents, and started in company with the army. In the outskirts of the city, when passing the residence of Mrs. Elmore, she concluded a fair exchange was no robbery, so she left her old equipage and took in its place a fine carriage of Mrs. Elmore. It was said that when passing Society Hill she by mistake loaded up and took off the family silver of the Witherspoons, a prominent family, at whose house she stopped, and who had put their silver in her room for safety. In December 1865, when in New York, I received a note from Mrs. Feaster begging me to call and see her at the Astor House. On doing so I found her living in style, with a handsome suite of rooms and surrounded by a number of army officers. She was then working up her claim for loyalty and wanted me to giver her a certificate as mayor of Columbia that she was a widow. As I had seen Mr. Feaster but a few days previously in Columbia I was not able to help her, but I heard that she recovered $10,000 for her loyalty—General Sherman having testified that he had witnessed the destruction of her property. Miss Boozer soon after married a wealthy gentleman and now resides, I believe, in Baltimore. It had been stated that she and her younger sister were the parties that were mixed up with the crown prince of Russia, a few years ago, and the loss of his mother’s diamonds.

I find that were I to continue in describing the incidents of that eventful night that I would greatly lengthen what I at first intended as merely an account of the conflagration, so I will conclude; but must mention that I was present in the office of Governor Orr, some time in 1867, when General Howard, then visiting Columbia, was there. Seeing General Hampton across the street, I hailed him from the window, and when he entered Governor Orr introduced him to General Howard. The first thing General Hampton said was: “General Howard, who burned Columbia?” General Howard laughed and said, “Why, General, of course we did.” But afterward qualified it by saying, “Do not understand me to say that it was done by orders.”