A hand-knit Christmas stocking is bound to be a treasure for years to come, whether you lovingly knit one as a gift or create a set for your own family. In the pages that follow, we offer a wide variety of styles, so you’re sure to find one that’s perfect for the spotlight it will claim in your home. Some of our patterns are as traditional as the holidays themselves, while others offer a new twist to classic ideas, with their bright and surprising color combinations. You’ll find several felted knitting projects, multicolor patterns, and some interesting textural designs. Some of the stockings are extra large; in contrast, you’ll find mini socks, as well as miniature mittens and sweaters just right for hanging on the tree or even packaging small gifts. Everyone seems to want to knit socks these days, and knitting a roomy Christmas stocking is a wonderful way for novice knitters to learn some basic sock-knitting techniques. Plus, no second-sock syndrome: you have to knit only one! So choose a pattern from our collection of talented designers, pick up your needles and yarn, and get set to knit a true Christmas heirloom!

“Real” socks must fit a three-dimensional foot and, for comfort’s sake, have few or no seams. Knitted from top to toe, in the round on circular or double-pointed needles, socks are shaped as you knit. Here’s a brief rundown of the basic structure to help you envision your sock project as a whole.

Each stocking in this book starts at the top by knitting the cuff and then the leg. When you get to the ankle, you set aside the stitches across the top of the foot (the instep) on a spare needle or stitch holder and, for just this section, knit back and forth on straight needles to create a little rectangle called the heel flap. Next, you pick up stitches along both sides of the heel flap, retrieve the instep stitches, and again begin to knit circularly. To accommodate the wider shape of the foot at the ankle, the diameter of the sock is wider here than at the leg and along the length of the foot, so in order to narrow the stocking again to create the foot, you make a series of decreases at each side of the heel, forming the gusset. When the foot is the desired length, you shape the toe with further reductions. Close off the toe stitches, and your stocking is ready to hang!

Today’s yarn selection makes knitting more fun than it’s ever been before. The stockings in this book were knit with yarns of varied fiber content and weight. We tell you exactly which yarns the pictured stockings were knit with, but we hope that you’ll enjoy experimenting with your own color combinations and yarn varieties — wool, cotton, synthetics, and blends, and maybe even luxury fibers. After all, a very special stocking may someday become a family heirloom. The choice is yours, as long as you keep in mind that you must get the gauge indicated by the pattern (see page 10). Also, if you choose one of the felted projects, be sure to use only 100 percent wool or another animal fiber that will shrink effectively (see Yarns for Felting, below).

Be sure to buy enough yarn to complete your project. You’ll find information about the number of skeins needed for each pattern in this book, along with the weight and yardage of the skeins we used. If you substitute, be sure to compare your yarn’s yardage to the pattern requirement. Yardage is usually listed on the label; if not, ask your yarn shop to check the manufacturer’s specifications. It’s always a good idea to buy an extra skein to avoid running short; most yarn shops accept returns of untouched skeins of yarn as long as you do so within a reasonable length of time. Check your shop’s return policy.

If you’re new to knitting, abbreviations can seem like a foreign language, so in this book we’ve avoided overusing them as much as possible. Here’s what you’ll find:

CC - contrasting color

K - knit

K2tog - knit 2 stitches together

M1 - make 1 stitch

MC - main color

P - purl

P2tog - purl 2 stitches together

psso - pass slipped stitch over

ssk - slip, slip, knit the two slipped stitches together

yo - yarn over

Any animal fiber, such as wool, alpaca, and mohair, will felt, as long as it hasn’t been pretreated. Washable (superwash) wool, bleached white wool, cotton, rayon, silk, and synthetic fibers don’t felt. Many off-white and light colors do not felt well, if at all. It’s not unusual to find that different colors of the same yarn felt differently. Some yarns require a longer period of agitation than others, or they may not ever achieve the degree of felting desired. Making swatches is always a good idea, but before jumping into any felted knitting project, it’s especially important to knit and felt a swatch with the yarns you’ve chosen. (For more about felting, see page 125.)

Most knitters have strong preferences when it comes to selecting knitting needles, and the wide variety of choices can be confusing until you try them. Coated aluminum needles are durable but sometimes heavy in larger sizes. I find that slippery yarns tend to slide rather easily off metal needles. Plastic or similar materials are lighter, though they can bend or break, and yarn sometimes sticks to them. Depending on the yarn you’re working with, bamboo or wood needles may be a good compromise. The yarn moves smoothly along them, even in hot, sticky weather, and they’re quiet and comfortable to use.

Most of the patterns in this book are knit on double-pointed or circular needles. Available in several lengths, circular needles have a flexible nylon or plastic center cable. Double-pointed needles come in sets of four or five. If you’ve always used four for knitting in the round, you’ll find knitting with five is easier and less likely to leave telltale lines (known as ladders) between the needles.

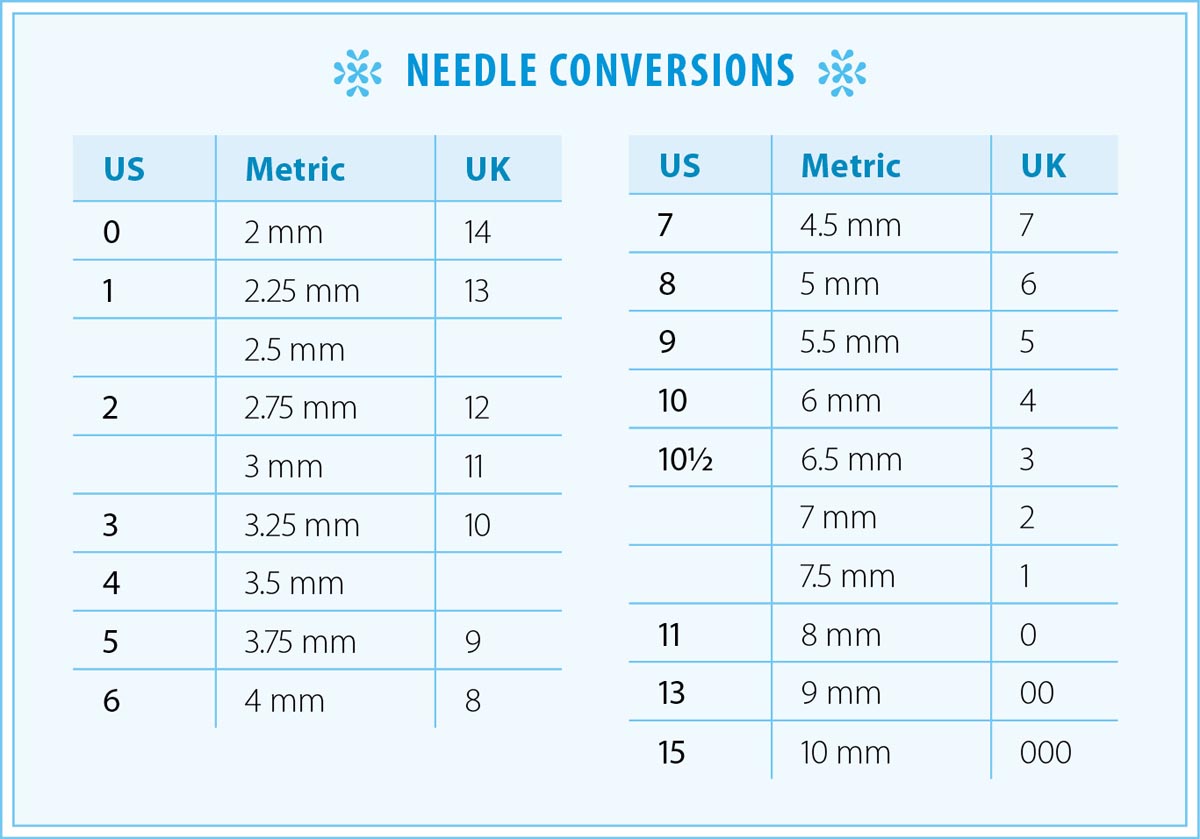

The size of knitting needles is indicated by number. It’s important to note whether the size is US, UK, or metric — they’re all different! The chart on page 8 gives equivalent sizes for all three. You’ll note that in the US system 0 is very small, whereas in the UK system 0 is large. This book provides US and metric (but not UK) sizes in all the instructions.

Although you can get started on most projects with little more than yarn and needles, a nice, well-supplied knitting bag, like all tool kits, makes life easier. Here are some suggestions for things you might need:

You may have heard enthusiastic new sock knitters proudly talk about learning to “turn the heel.” Although it may sound somewhat esoteric, there’s really no mystery to turning a heel, once you understand the principle. Turning the heel is a key step in shaping the stocking, taking you from the tube that forms the leg, accommodating the larger-diameter section around the ankle, and merging into the slimmed-down area that is the foot.

The heel is turned by working what are known as short rows at the bottom of the heel flap (see Anatomy of a Sock, page 5) while you’re still knitting back and forth in rows and before you begin to knit the instep circularly. The number of stitches in the heel flap varies from pattern to pattern, of course, but you are usually instructed to knit about two-thirds of the way across the row, work two stitches together, knit another stitch, and then turn to go back the other way, leaving the remainder of the stitches behind, unworked. The trick is that you must believe this and follow the directions, even if they seem odd to you! If you are working stockinette stitch, you slip the first stitch after you turn, then purl a certain number of stitches, but only as far as the pattern directs. Again, work two stitches together, purl one, and then turn to go back the other way. This is when you see the magic begin! When you come to the place in the row where you turned (just after the two stitches you worked together), you’ll see a very noticeable gap between the slipped stitch of the row before and the first unworked stitch. Work the two stitches on either side of the gap together, work the next stitch, and turn. The pattern directions will inform you about the number of stitches to work, but you’ll soon get used to the visual clues and be able to confidently anticipate where to decrease. Continue in this way until all the stitches have been worked.

When working short rows as described above, some sock knitters use a “wrap and turn” (W&T) method to eliminate the small hole that may appear when you turn in the middle of a row. On knit rows, work up to the turning point, slip the next stitch purlwise onto the right-hand needle with yarn in back. Move the yarn between the needles to the front of the work, return the slipped stitch to the left-hand needle, and turn to work in the other direction. If you’re working stockinette stitch, move the yarn between the needles to the front and begin to purl; if you’re working garter stitch, leave the yarn at the back and begin to knit: W&T is complete. On purl rows, work up to the turning point, then slip the next stitch purlwise onto the right-hand needle with yarn in front. Move the yarn between the needles to the back of the work; return slipped stitch to the left-hand needle, and turn to work in the opposite direction. Move the yarn between the needles to the back and begin to knit: W&T is complete.

Even though Christmas stockings don’t have to fit and you want to get going on your project just as soon as possible, it really does pay to take time to knit a swatch. Gauge matters even when fit doesn’t, as the perfect gauge means that your fabric isn’t either sleazy because the stitches were too loose, or stiff because the stitches were crammed in too tight. Swatching is how you test the number of stitches per inch you’ll be getting with the yarn and needles you’re using. Always calculate your gauge over at least 4 inches. That’s because counting stitches over just 1 inch can be misleading if your stitches are uneven or the stitch count within that inch comes up with a fraction. Here’s an example of how to knit a swatch and figure out gauge:

Step 1. If the pattern gauge is 16 stitches = 4 inches on size US 7 (4.5 mm) needles, use these needles to cast on about 24 stitches. (You need a few extra stitches so that you don’t have to measure the edge stitches, which may be uneven or draw in.)

Step 2. Following the stitch pattern you’ll be using for the main part of your project, knit a swatch about 5 inches long. Block it as you plan to block the finished item

Step 3. Lay the swatch on a firm, flat surface, taking care not to stretch it. Uncurl the side edges and lay a flat ruler across the swatch. Count the number of stitches within 4 inches. There should be exactly 16.

Step 4. If your swatch contains more than 16 stitches in 4 inches, use larger needles and knit another swatch, repeating steps 1 through 3. If your swatch contains fewer than 16 stitches in 4 inches, use smaller needles and knit another swatch, repeating steps 1 through 3.

Measuring gauge

Note. Always use fresh yarn to check your gauge. Used yarn may have stretched and thus give an inaccurate measurement. Also, if two needle sizes are specified for a pattern and you change your larger-size needles to obtain the correct stitch gauge, adjust the size of the smaller needles to correspond. Finally, even after you have established what needle size and yarn gives the right gauge, check again after you have knitted a few inches into the project to make sure your gauge is holding true.

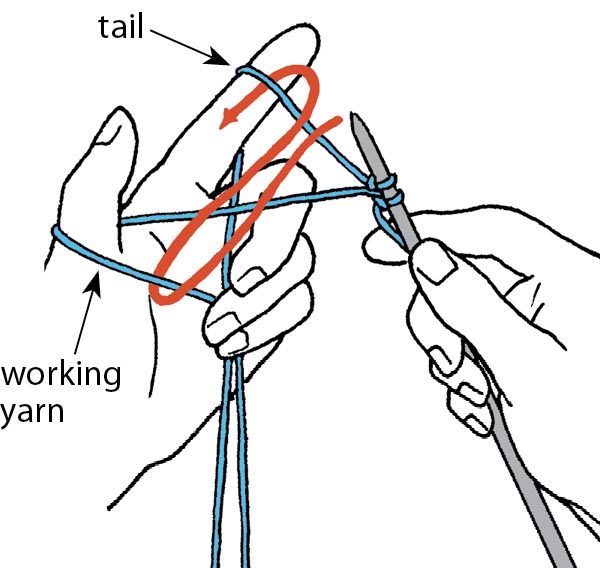

Using a long-tail cast on makes an especially neat, firm but elastic edge. If you tend to cast on tightly, you may want to switch to one needle size larger for this step.

Step 1. Estimate how long to make the tail by wrapping the yarn around the needle one time for each cast-on stitch you need, then adding a few extra inches. Make a slip knot right here, and slide the knot over a single knitting needle. Hold that needle in your right hand; hold the tail and the working end of the yarn in your left hand as shown. Insert the needle over the front of the tail on your thumb and up through the middle of the loop.

Step 1

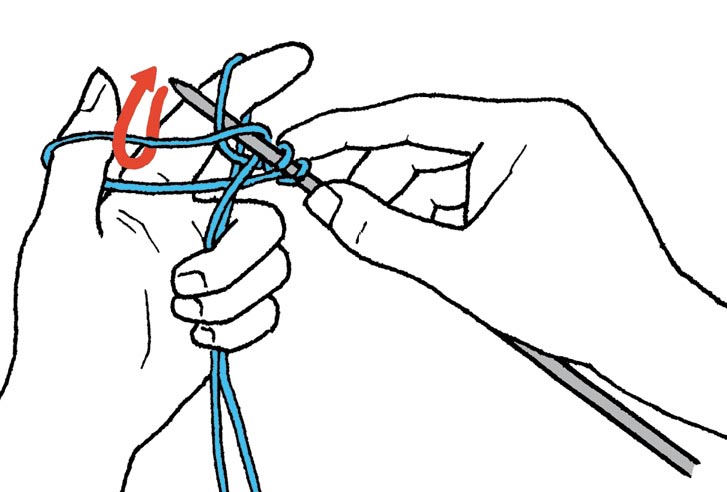

Step 2. Insert the needle over the front of the working yarn on your index finger and draw a loop of it through the loop on your thumb.

Step 2

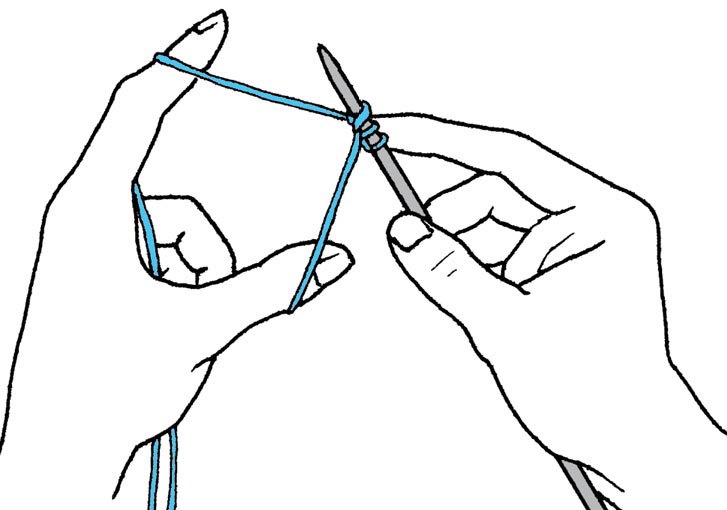

Step 3. Release the loop on your thumb, place your thumb underneath the tail, and snug the new stitch onto the needle. The stitch should be well formed, but not too tight. As you make additional stitches, try to keep them as consistent as possible.

Step 3

Binding off is sometimes called casting off. The simplest way to bind off is to work two stitches, then draw the first one over the second. Don’t pull too tightly, or your edge will be puckered and inelastic. Continue to work a stitch, then carry the stitch already on the needle over the newly made one. When you reach the last stitch, pull the working end through the stitch.

Binding off

If you tend to bind off tightly, you may want to switch to one needle size larger. Or, try this:

Step 1. Work two stitches. Insert your needle in the first stitch, use the left-hand needle to draw it over the second stitch, but instead of completing the bind off and dropping the first stitch, leave it on the left needle.

Loose-method bind off, Step 1

Step 2. As you work the next stitch, allow the first stitch to drop off the needle.

Loose-method bind off, Step 2

Continue in this way until all stitches are bound off.

This is a useful technique if you want to bind off and join two pieces in an invisible seam at the same time. Place half the stitches on one needle and half on a second needle. Holding the needles in your left hand, bring the two pieces, or two halves, together with the right sides facing. The tips should be pointing in the same direction, with the yarn attached to one of the halves at the beginning of the needle.

Three-needle bind off

Step 1. Insert a third needle through the first stitches on the front and back needles, and knit them together.

Step 2. Make a second stitch in the same way, and then pass the first stitch over the second one. Repeat until you’ve bound off all stitches.

Note: Instead of executing this technique with right sides together, which creates an invisible seam on the right side of the fabric, you can do it with wrong sides together, creating an interesting raised design element on the fabric.

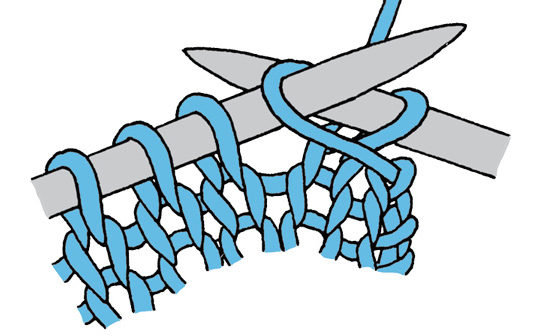

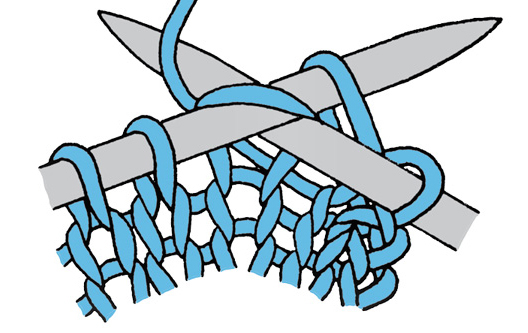

As with increasing, decreasing can become an interesting design element in your project, and pattern directions usually specify which method to use. The three techniques shown here are the most common. Because the first two (ssk and psso) result in a finished stitch that slants to the left, they are often used at the right-hand side of an item; the last method (K2tog) results in a right-slanting stitch and so is used on the left-hand edge.

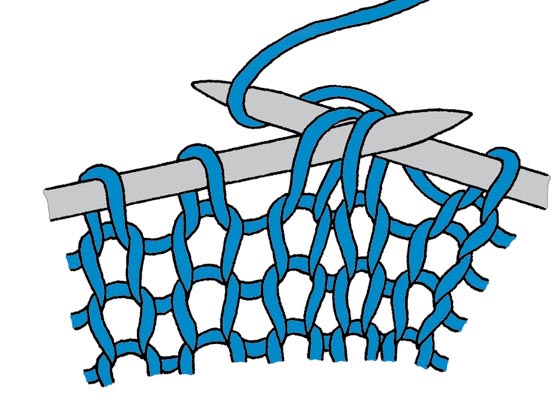

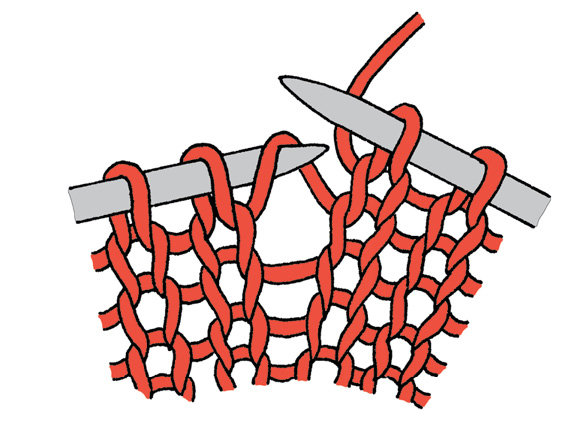

The first method is called “ssk” (slip, slip, knit the two slipped stitches together). Slip two stitches, one at a time, from your left-hand needle to your right, as if to knit (knitwise). Then slide the left-hand needle from left to right through the front loops of the slipped stitches, and knit the two stitches together from this position. This technique makes a finished stitch that slants to the left on the finished side and is often used at the beginning of a row.

ssk

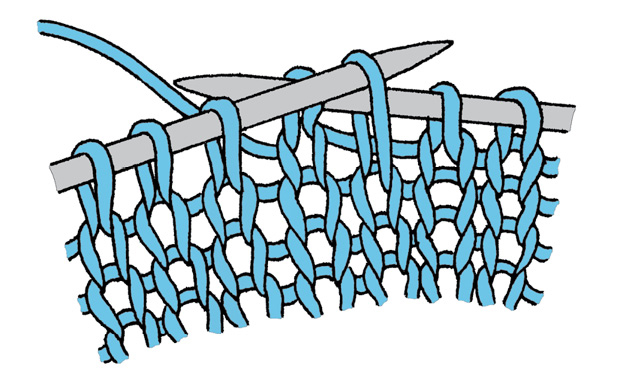

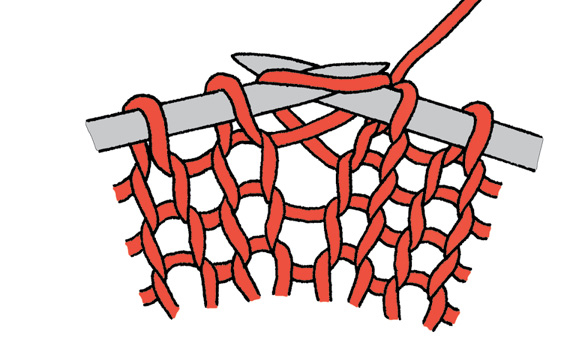

To “psso” (pass slipped stitch over knit stitch), slip one stitch from the left- to the right-hand needle, inserting the needle as if to knit the stitch, but without knitting it. Knit the next stitch, then draw the slipped stitch over the just-knitted stitch. The finished stitch will slant to the left on the finished side.

psso

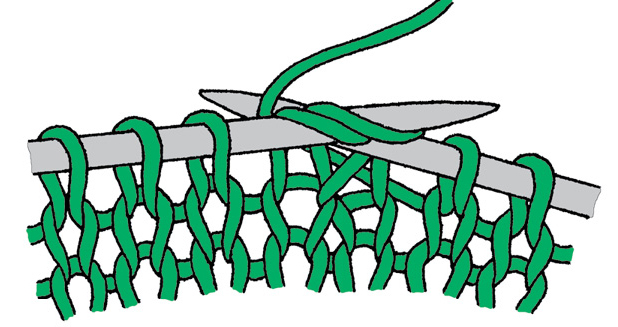

For a finished stitch that slants to the right on the finished side, simply knit two stitches together by inserting the needle into both loops, just as you would to knit. K2tog (knit 2 together) is generally used at the end of a row.

K2tog

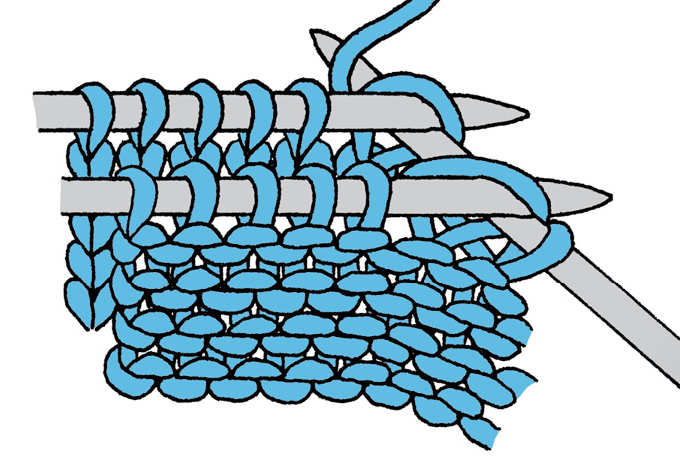

Increases allow you to shape your knitting as you work. Sometimes you’ll want these increases to be invisible, but in other cases the increase stitches are not only noticeable but important design elements. It’s helpful to learn a variety of techniques so that you can pick and choose whatever is appropriate for your needs. The illustrations that follow show three increase methods: bar increase, make 1 with a right slant, and make 1 with a left slant.

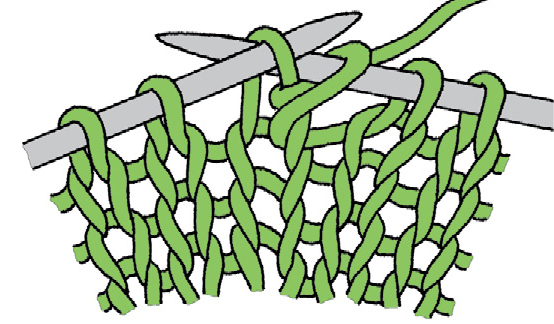

The bar increase is a tight increase that leaves no hole but shows as a short, horizontal bar on the right side of the fabric. Make it by knitting into the front of the loop in the usual way, but do not remove the stitch from the needle. Instead, knit into the back of the same stitch, and slip both new stitches onto the right-hand needle. This is often called a knit-front-back (kfb) increase.

For a bar increase of two stitches, work into the front loop, the back loop, and the front loop again before taking the three new stitches off the needle.

Bar increase

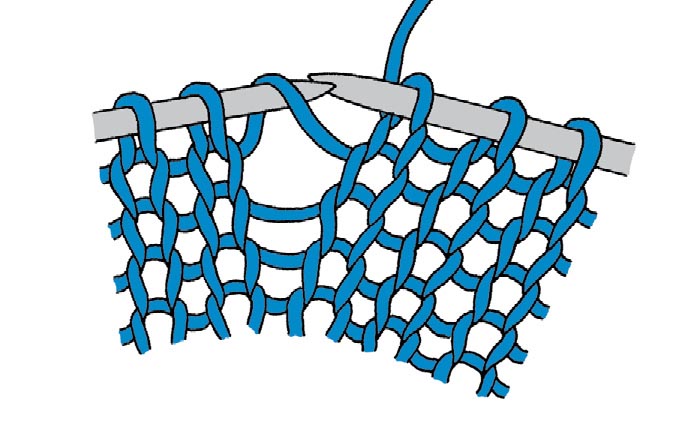

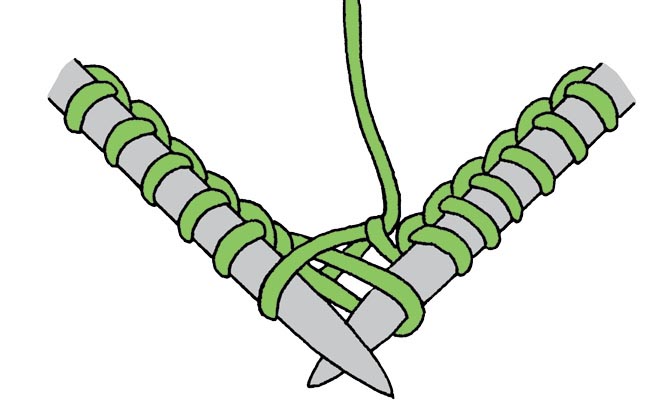

Step 1. Look for the horizontal bar between the first stitch on your left-hand needle and the last stitch on your right-hand needle. With the tip of your left needle, pick up this bar from back to front.

Step 1

Step 2. Knit into the bar from the front, which twists the new stitch and gives it a slant to the right. Even though it may seem a bit difficult to get your needle into the bar from front to back, it’s important to do so in order to avoid creating a small hole in the fabric.

Step 2

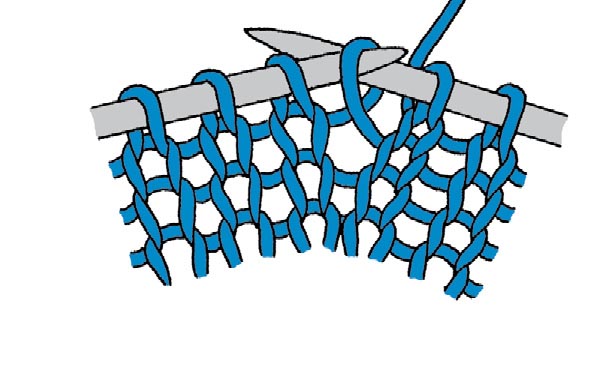

Step 1. Again using the tip of your left-hand needle, pick up the horizontal bar between the first stitch on your left-hand needle and the last stitch on your right-hand needle, this time from front to back.

Step 1

Step 2. Now, knit into the back of the bar, which twists the new stitch to the left.

Step 2

Note: To make 1 at the end of a round, pick up the horizontal strand between the first and the last stitch of the round.

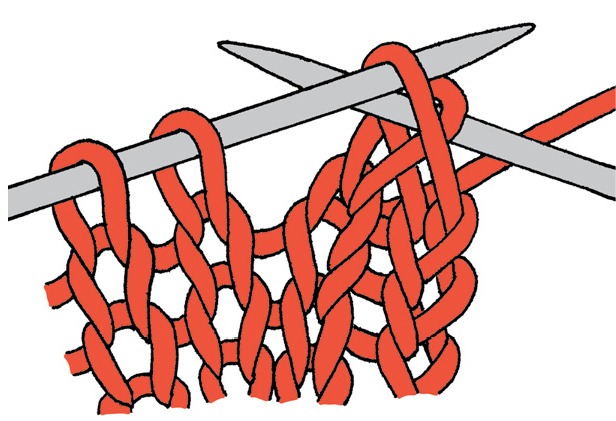

Most of the knitting in this book is done on either circular or double-pointed needles, using a technique known as working in the round. Since you shape the item as you knit, there’s usually little or no assembly to worry about once the knitting is complete. To make stockinette stitch when you knit in the round, you always knit on the right side, continuing around the circular or double-pointed needles without ever turning your work. (On straight needles, stockinette is created by knitting on one side, turning, and purling on the return.)

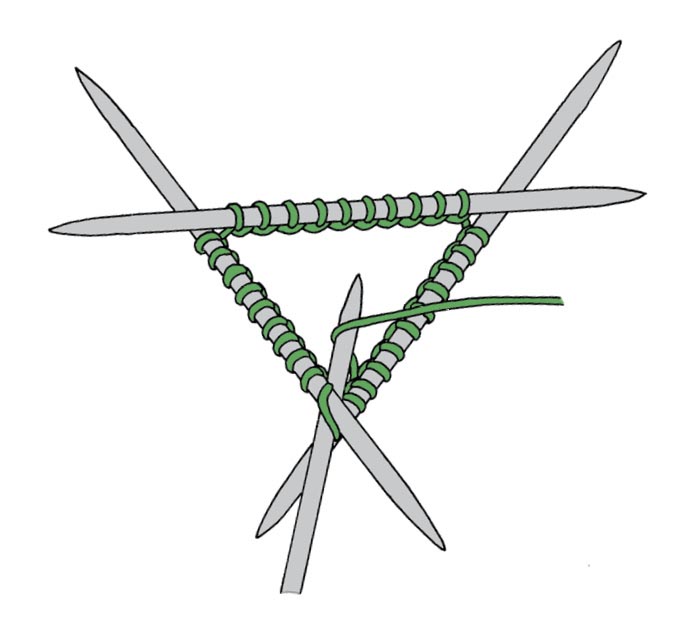

Setup for knitting with four double-pointed needles

To knit with double-pointed needles, cast on the correct number of stitches for your project, and divide the stitches evenly among three (or four, if you’re using a five-needle set) of the needles (or as the pattern directs). Lay the work on a flat surface, forming the three needles into a triangle (or forming four needles into a square). Arrange the cast-on stitches so they are flat and their bases all face toward the center of the triangle. Look carefully along the needles, and especially at the corners, to make sure that the stitches don’t take an extra twist around the needle.

The next step is the trickiest: Carefully lift the needles, keeping the stitches aligned, and use the working yarn that formed the last cast-on stitch to knit the first stitch on the left-hand needle. Snug the yarn firmly before knitting the second stitch. (Do not tie to join.) Knit across until the left-hand needle is empty. Use the empty needle to knit the stitches on the next needle. Continue knitting until the first round is complete. Place a split-stitch marker or a safety pin on the fabric between the first and last stitches to indicate the beginning of each new round, or use the cast-on tail to keep track.

Knitting designer Betsy Lee McCarthy (see her pattern on page 32) offers this tip for making a smooth, secure join when getting started to knit in the round: Distribute the stitches among the needles as indicated in the pattern, then check to make sure they are not twisted. Hold the needle with the first cast-on stitch in your left hand, and the needle with the working yarn and the last cast-on stitch in your right hand. Place the skein so it will be outside the circle once the yarn is joined. With the tip of the right-hand needle, slip the first stitch on the left-hand needle to the right-hand needle. With the left-hand needle, lift the last cast-on stitch on the right-hand needle up and over the first stitch and onto the left-hand needle. It is now the new first stitch on the left-hand needle. In other words, make the first and last stitches of the cast on trade places. Pull both ends of the yarn to snug up. You may want to place a marker between the two stitches to indicate the beginning of the round.

To knit with circular needles, cast on the correct number of stitches as usual, then lay the work on a flat surface. Arrange the stitches so that they face the center of the circle and carefully knit the first couple of stitches on the left-hand needle, taking care not to twist any stitches around the needles. Snug the yarn tightly between the last cast-on stitch and the first stitch in the first round. (Do not tie to join.) Place a marker between these two stitches to help you keep track of rounds.

Knitting in the round can be relaxing and fun if you develop just a few good habits. Here are some tips to make it easier:

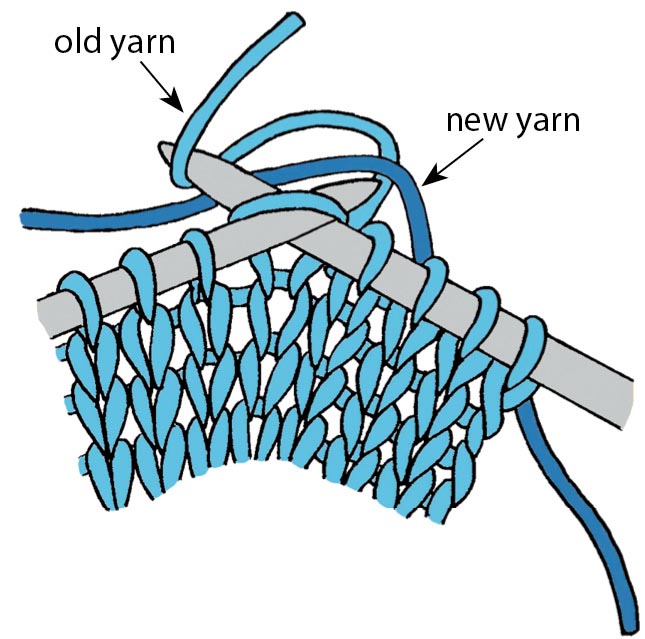

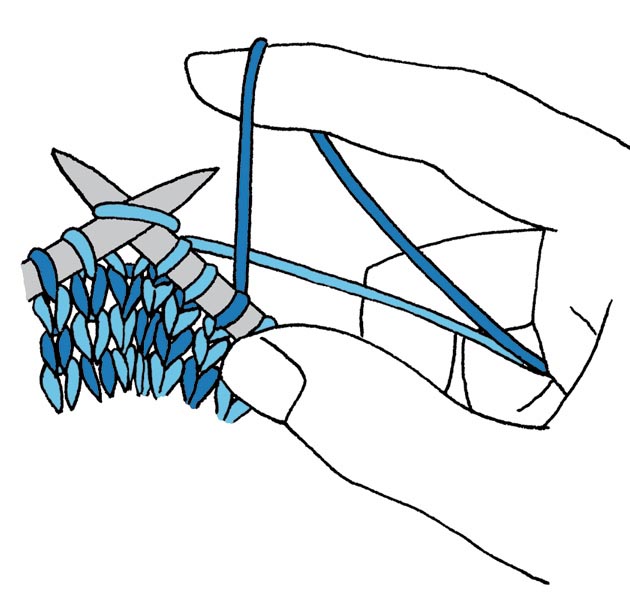

When you run out of yarn and need to start a new end, do so toward the edge of the stocking, where the join is less likely to be noticed. To make the join, lay the new end along the back of the work, and carry it forward for six or seven stitches by weaving the working yarn over and under it as you knit, in much the same way that you handle a second color yarn in multicolor knitting (see The Joy of Color, below). Once it is snugly woven in in this manner you can simply pick it up and begin knitting with it. Weave in the tail of the old yarn when your work is complete. If you follow this procedure faithfully throughout a project, you will have few ends to darn in — and you’ll thank yourself heartily for that!

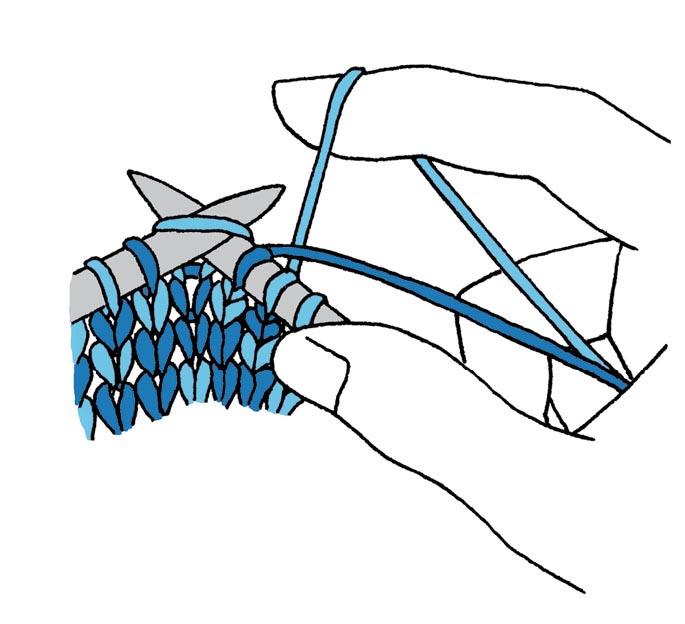

Weaving in new yarn before knitting with it

You can create an infinite number of fascinating designs by knitting with two or more colors in a single row or round. The multicolor knitting in this book is called stranded knitting, in which two (or more) colors interchange regularly all the way across the row. We illustrate the sequence of colors in charts that are color-matched to the photos of the finished projects. Begin charts at the bottom right. (The words start here and an arrow will help you find your place.)

When you change colors within a row, always take the color you want to emphasize from below the other. On the front, the color handled this way will dominate the pattern and create a more uniform design. Be sure to be consistent and take the same yarn over and the other under throughout the project.

When you knit with more than one color, carry the other color or colors along on the wrong side. Keep the carried yarn loose and don’t carry it for more than three stitches. For wider runs in the pattern, catch the carried yarn by wrapping the working yarn around it from underneath every three or four stitches.

Lifting dark color over light one

Bringing light yarn from underneath

Designers Deb and Lynda Gemmell (see their pattern on page 70) offer this tip for making a smooth transition from one color to the next: Sew the tails with a yarn needle from the beginnings of the stripes up and to the left. Sew the tails from the ends of the stripes down and to the right. This trick helps disguise the “jog” where a new color starts.

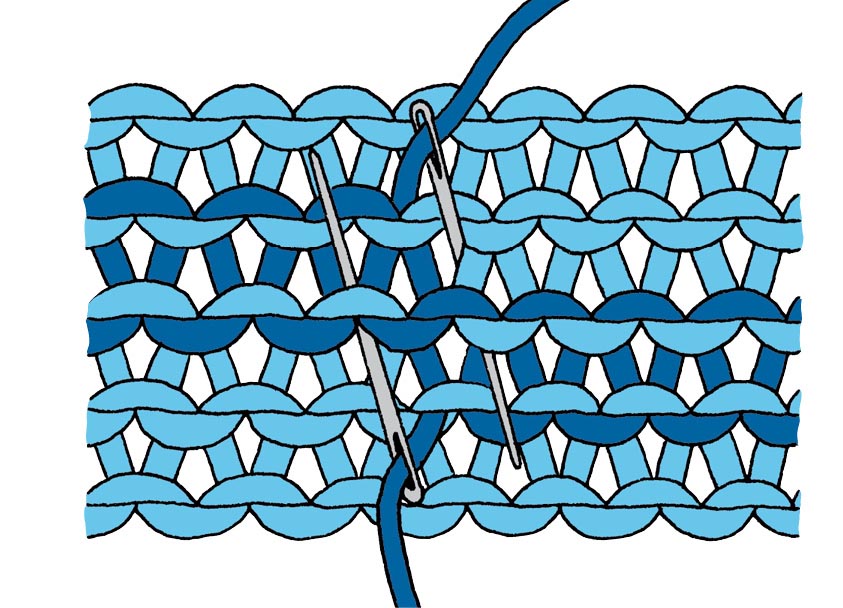

Hiding a color jog

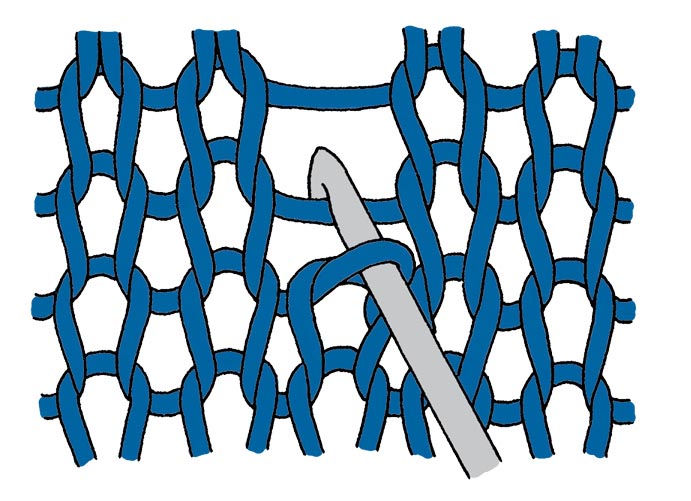

Beginning knitters often panic when they drop a stitch. It’s empowering to discover how easy it is to pick up dropped or half-made stitches. Working on the right side of stockinette stitch, find the last loop that’s still knitted and insert a crochet hook from front to back. Pull the loop just above the bar between the adjacent stitches, catch the bar with your hook, and draw it through the loop. If you have to pick up a number of stitches, take care to pick up the bars in the correct order.

Picking up a dropped stitch knitwise

You may be anxious to see your beautiful new creation hung by the chimney with care, but do take the time to weave in any loose ends you missed on the wrong side of the fabric, then block it properly. You’ll be surprised at how unevenness disappears when you block your knitting.

You can steam-block all-wool fabrics by holding a steam iron just above the surface so the steam penetrates the fabric, or cover the surface with a wet pressing cloth and lightly touch the iron to it. Either way, avoid pressing hard or moving the iron back and forth. Never iron or block a ribbed hem; it will lose its elasticity.

For wool blends, mohair, angora, alpaca, or cashmere, just dampen the knitted piece by spraying it lightly with water, then pin it to a flat surface where you can safely leave it to air-dry. Be sure to pin it so that corners and the stitches line up straight.

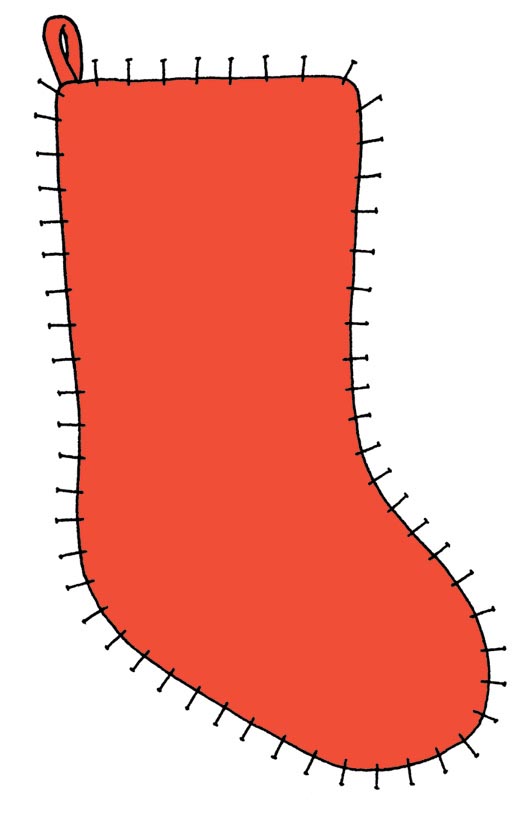

Blocking by pinning sock out to size