THE LIPIZZAN IS A POWERFULLY built animal, yet he is the ballet dancer of the horse kingdom. To the Old World music of gavottes and mazurkas he performs the most difficult routines—springing along on his hind legs without touching ground with his front ones, pirouetting in delicate canter motion, leaping upward into space and, while in the air, kicking out his hind feet. So perfect is his rhythm one would think he had a metronome for a heart!

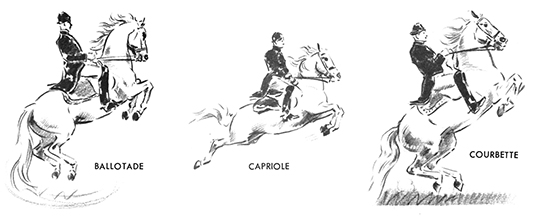

These leaping, thrusting movements are called courbettes, caprioles, levades, ballotades. Spectators often forget the names, but they never forget the breathless moment when a Lipizzan turns himself into a flying white charger.

Lipizzans are a very old and pure breed. They may be traced back to the year 1565 when Maximilian II, emperor of Austria, decided that his knights needed a riding school like the one he had visited in Spain. The horses trained in it would be beautiful to show in times of peace, and in war they could spring at the foot soldiers of the enemy until they fled in fear. Accordingly Maximilian imported Arabian stallions into Austria and crossed them with Spanish mares. Their descendants became the dazzling white Lipizzans, so named because they were foaled in the little town of Lipizza near the Adriatic Sea.

• • •

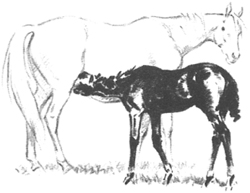

Maximilian commanded that only the stallions be allowed to attend his new Spanish Riding School on the palace grounds of Vienna. And to this day the mares are never ridden; they and their foals live a life of freedom.

Lipizzan colts are a long time growing up. Thoroughbred and Standardbred colts race in public meetings when they are two-year-olds, but Lipizzans run and frolic with their mothers for the first four years of their lives. A pasture dotted with brood mares and foals is a strange sight, the foals dark brown, the mares milk white. Born dark, the youngsters gradually lighten in color, graying at three and becoming pure white by the time they are ten.

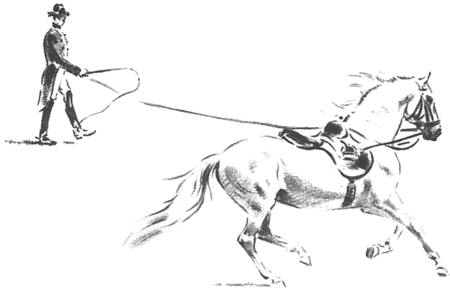

Until all the colty foolishness has gone out of them, the young Lipizzans remain at the nursery. Then, at four, they are sent off to school to learn rhythm and manners and acrobatics. Their first lesson is with the lunge rope. Round and round in a circle the groom drives his pupil at the end of a long rein. Not until the horse is five years old does he feel a saddle on his back and a bit in his mouth. Then he is walked only, sometimes for months. But what a walk it is! Long, free supple strides, neck reaching out, muscles relaxed. A rhythmic movement.

At six the real training begins, the difficult ballet movements. One movement leads into another naturally, for the rider-trainers are superb teachers. Their commands are spoken in low tones. Their homemade birch whips are cues, not punishing rods. And always their pockets bulge with carrots for good behavior.

When the rider sits his horse, he seems to have a ramrod for a backbone. The fact is that, as an apprentice, he rode for days with an iron bar sewed into the back seam of his riding coat. He appears to sit stone-still; yet he is constantly giving signals. In the canter, for example, he sometimes asks his mount to change leads with every stride. If he wishes his horse to take a left lead, he brings back the calf of his right leg, but only a trace. He turns his horse’s head toward the left, but only a hair’s breadth. He shifts his weight onto his right seat bone. He brings back his left shoulder. But all of these signals are so fine that only the horse is the wiser. Muscle control must be learned by the rider as well as the horse! Small wonder, then, that apprentice grooms start out when only nine or ten and are still learning at sixty-five, even though they are masters. The young apprentice learns most from the fully trained horse, and the green horse from the experienced master. Then, all along the years, trainer and horse continue to learn from each other, growing wise together.

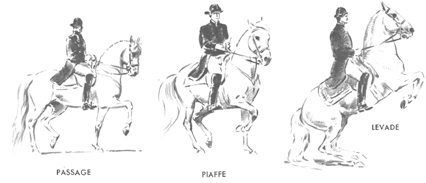

As soon as the canter has become habit, then the stallions are ready for the quadrille. In two-four time, to the strains of a Mozart minuet, they are taught to dance in graceful maneuvers. From the quadrille they graduate to the passage. This is a slow-to-medium trot which looks as if the feet approach, rather than touch, earth. Diagonal legs strike out in unison, and the action of the forelegs is extremely high. The passage is not spectacular. Rather it is slow, measured beauty.

The piaffe next! Piaffe is a French word, meaning to prance. The piaffe is just that—prancing in place, not in stiff movements like a toy soldier, but like a ballet dancer getting ready for an especially intricate routine. In the case of the Lipizzan he is getting ready for the levade—the greatest test of a horse’s balance. In this exercise he crouches on his hind legs as if he were sitting on his haunches; then slowly he rears until his body reaches a forty-five degree angle, which is far more difficult than if it were held erect. Forelegs tucked under his belly, a thousand pounds of weight poised, he becomes a white stone statue. The best stallions in the school can stand the strain of this pose for no longer than fifteen seconds.

Not all Lipizzans go further in their schooling. Only the very strong can do the ballotade, which is a spectacular leap with the hind legs tucked under the belly. Or the capriole, in which the horse springs into the air and, while he is at his highest elevation, thrusts his hind legs out until he is the winged Pegasus come alive.

Time and again wars threatened to destroy the Spanish Riding School. In the second World War the Nazis spirited the Lipizzan mares and foals away from Austria and hid them in Czechoslovakia. Meanwhile, at the school, Colonel Alois Podhajsky, chief riding master, tried to save his stallions—rationing their oats and hay, building air-raid shelters for them. But even in the shelters their safety was threatened, for the enemy were moving in closer and closer. Finally the Colonel loaded his pupils on freight cars but could not get them out of the danger zone.

Just when the future looked blackest, U.S. General George S. Patton, Jr., came to the rescue. An expert horseman himself, he asked to see the horses perform. So impressed was he that he wanted to save the breed for future generations. He furnished a convoy of armored tanks to bring the mares and foals back to Austria. And when he was killed, General Mark Clark saw to it that the stallions were escorted to the little town of Wels in the American zone of Austria. There, on a peaceful, grassy plain, the Spanish Riding School carried on.

In October, 1950, the same Colonel Podhajsky brought fourteen of his star pupils to America to show the New World the finest horsemanship of the Old. More than a hundred thousand people surged into Madison Square Garden in New York to see the exhibition of the white stallions.

Applause comes easily to Americans but, watching the marbled beauty and the spectacular routines of the Lipizzans, the onlookers sat frozen in admiration. Never before had they seen a horse ballet. The quiet ovation had to come first. Then, like a dike of water unleashed, the applause burst forth.

Before it died away, some horse fans thought, and some said, the stallions must have been severely handled, cruelly treated, to perform so precisely. But how could the casual onlookers know of the long, patient years of training? How could they know that the superb steps are not stunts but that each graceful movement is a copy of high-spirited horses at play or in combat?

And how could they possibly know that, when the white stallions are turned out to grass, they take a busman’s holiday? With no audience at all and no riders to cue them, and no music but wind whispers, they spring into a capriole just as boys and girls turn a cartwheel—for the sheer joy it brings!