BLUE RIBBONS, RED RIBBONS, YELLOW ribbons, white ribbons! In show classes for ponies, sometimes there is more than one kind of champion—the blue-ribbon pony and also the boy whose pony just misses.

For one hurt second the boy blinks back his tears, pretending he doesn’t care. And then in a flash he really doesn’t. He remembers the time his pony carried him down the slippery sides of a stone quarry until they stood in the very bottom of the cup, then up and up again to the dizzying rim above the whole wide world. And he remembers the day his pony jumped across a deep ravine and all the others balked.

Remembering all this, he strokes the sleek neck, swings astride, and bravely trots his pony out of the ring behind the winner.

The judge, with a deep sigh of relief, mops his forehead. “There go two champions,” he mutters to no one at all, “the light gray Welsh and that thoroughbred boy astride the dark one!”

More and more, big shows and small ones are offering classes for the best ponies, and more and more the finely made Welsh is coming out of obscurity to carry away the blue ribbons. He is frequently the graduation mount for the boy or girl whose legs have grown too long for the Shetland.

Who would suspect that the ancestors of this delicately made pony were half-wild refugees, hiding in the craggy mountains of Wales, escaping one enemy only to meet another?

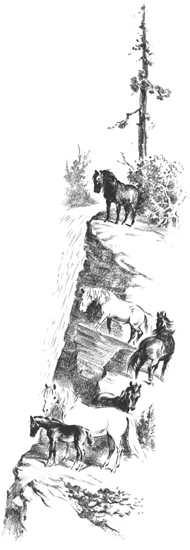

First they were hunted and tracked down by the sheep herders, who looked upon them as thieves of the juicy grasses belonging to their sheep. Often the herders would capture a band, kill off the colts for food, and throw the scraps to their dogs. These sheep dogs were strong as wolves and, once having tasted pony meat, they hunted the little fellows themselves, stealing up on them silently without the least warning. A mare would be grazing peacefully and suddenly she would look up to see a snarling dog ready to leap at her foal. In a flash she was between them, springing at the killer with her forefeet, then driving her young one into a gallop through narrow passes, up a steep scarp, leaping from ledge to ledge until at last they were safe in the folds of the mountains. Tiny colts only a few weeks old had to learn to take their first jumps to save their lives. Some were strong enough to escape; when they did they became nimble and wondrously wise.

But the sheep herders and their dogs were only small annoyances. The law was a bigger enemy. It reached out from the throne of England and shoved the ponies deeper and deeper into the mountains. King Henry VIII, with a gesture of his jeweled hands, decreed that “little horses and nags of small stature must be eliminated from the common grazing grounds.” As a result many ponies were killed and others fled into the mountain fastnesses. Here they found a quiet tableland high above the grazing grounds, and although the rocky soil furnished scanty herbage, the air was clean and clear, and sparkling cold drinking water bubbled down the mountainsides.

Yet even here they were attacked. Now winter was their enemy, biting with the sharp fangs of wind, howling into their ears, spitting hail and sleet at them. Sometimes the herds had to sneak down into the valleys to find food.

But hardships strengthen. And so it was with the ponies. Those that survived developed hoofs as flinty as the rocks they climbed, and hocks and haunches like steel springs, and lung and heart room to send them traveling like will-o’-the-wisps.

No! Enemies did not stamp out the spirited Welsh pony. They only made him stronger, hardier, wiser; and, above all, they preserved the purity of his blood. By not mixing with other breeds he has remained distinct.

There is a fineness about the Welsh pony, a kind of nobility in his bearing as if he knows that in his veins flows the blood of the Arabian. It shows in the refinement of his head, in his dished face, his “pint pot” muzzle, even in his color. Never is there a piebald or a skewbald among the true Welsh mountain ponies. They are bay, brown, or chestnut, with grays predominating, just as in the Arab.

At first people wondered how the blood of the horse of the desert found its way into the Welsh mountains. Then as they began to ask questions, it became clear. In faraway times had not the Romans invaded Wales? And was it not likely they had brought with them the spoils of their campaigns in Africa—the desert ponies that satisfied their eye for beauty and their need for quick flight? For four hundred years the Romans had occupied Wales, importing more and more Arabian horses which mingled with the native wild herds. Their offspring became pack ponies for the Romans, but they did not look like pack ponies at all. They had the elegant form of the Arabian, and they were fleet of foot like the Arabian—in truth, they were diminutive Arabians.

But Henry VIII was not one to appreciate the fine symmetry of these ponies. Hence his decree which almost wiped out the Welsh Mountain Pony.

It is a long road, however, that has no turning. Today the ponies still live high up on the tablelands, but when winter overstays, they are not afraid to nimble-foot down the mountains. The hand of man is friendly now. Even when it captures some of the fillies and colts for breeding purposes. The curious truth is that these creatures thrive in captivity; yet, no matter where they go, they cling to their wild pony characteristics. They jump a brush hurdle as high and clean as if a sheep dog were snapping at their heels, and at the walk or trot they pick up their feet and place them carefully as though testing the earth for loose pieces of shale. Even in America they have this “heather step.”

Perhaps the ponies of Wales are like the Welsh people who, in a changing world, cling steadfastly to their ancient language and customs. They are like them in another respect, too. On the Welsh coat of arms a motto describes the people. The words of the motto are Ich Dien, “I serve.” Every Welshman who understands pony character insists that Ich Dien describes the mountain pony, too, for he serves his master well.

No wonder he is a champion! And when the blue ribbon comes his way, he wears it in his headstall as if to the manner born.