FIVE MILES OUT IN THE Atlantic Ocean, off the eastern shore of Virginia, lie two tiny wind-rippled islands. They are as rich in horse lore as a mince pie is rich in raisins. Chincoteague (pronounced Shin-ko-teeg) is the smaller island, seven miles long and just twenty-one inches above the sea. Assateague is the bold outrider, protecting little Chincoteague from high winds and high seas.

Oystermen, clam diggers, and boat builders live on Chincoteague, but the outer island is left to the wild things, the wild ponies and the birds.

How the ponies came there is legend, but Grandpa Beebe, one of the natives, says, “Legends be the only stories as is true; facts are fine, far as they go, but they’re water bugs skittering atop the water. Legends, now, they go deep down and bring up the heart of a story.”

And so legend says that, way back in the yesterdays, a Spanish galleon was bowling along the deep when a great storm came up and blew the ship off its course. In her hold she carried live cargo—Spanish moor ponies headed for the mines of Peru. The ponies smelled the storm and plunged against their rough-built stalls, trying to escape. But it was the sea that finally set them free. It drove the ship onto a reef, cracking her hull open and spewing the ponies out of their dark prisons. In spite of the waves and the wreckage they thrashed their way to the nearest shore, and the first land they touched was the beach of Assateague.

Not a solitary soul lived on the whole island. And there were no fences anywhere. Only wide stretches of sand, and marshland with salt-flavored grass, and piney woods. Land and sea and sky were theirs, to be shared only with the black skimmer birds and the blue herons and clacking geese.

Always before, the ponies had been accustomed to man’s care. Now they had to rustle their own living. In winter they huddled in the woods, stripping the bark of pine trees, eating bark and needles, too, and they ate the myrtle leaves that stayed green. For drinking water they broke little mirrors of ice with their hoofs and drank the brackish water beneath. And they grew rough winter coats which took the place of man-made shelter. Snow sometimes sifted onto their backs and made a white fleece without melting, so heavy were their coats. Who minded winter? Not the ponies.

The Gingoteague Indians who used to hunt on the island now stayed far away. From their canoes they could see the ponies running wild along the shore, and the sight filled them with a nameless fear.

The white men, however, were unafraid. A few poled over to Assateague and built houses there, but by that time the ponies had grown to such numbers that they overran the island, trampling cleared plots and eating corn blades as fast as they pushed through the ground. In dismay the people gathered their belongings and sculled back across the channel to live on Chincoteague.

Today the outer island of Assateague is still a wildlife refuge, except for Pony Penning Day. On that day, late in July, the watermen on Chincoteague turn cowboy. Still wearing their fishermen’s caps and boots, they ferry their own riding horses over to Assateague to round up the wild ponies. It is the oldest roundup in America! Through bog and brier and bullrushes they ride, spooking the ponies out of little hidden places, driving them down to Tom’s Cove. At exactly low tide a signal is given and the wild herds, colts and all, are driven into the sea for the swim across to Chincoteague. The channel boils with ponies—stallions neighing to their mares, mares whinnying to their colts, colts squealing in panic. And all across the channel, oyster boats ride herd on the ponies, keeping them swimming toward Chincoteague.

At last, wet and blown, the wild things scramble out of the water, and a cheer goes up from the throng of visitors who have come to see the biggest Wild West Show of the east. In their mind’s eye they are selecting their own colt to buy at tomorrow’s sale, for Chincoteague ponies, captured early, make good, friendly mounts. The mares and stallions, of course, are too wild. After a day of being penned up in big corrals, they are driven back again to Assateague for another year of freedom.

Why are some of the ponies big and some small? Some solid color and some daubed with white? The reason is that at one time a Shetland stallion was turned loose on Assateague to run with the wild ponies. His influence is seen in the smallness of stature and the two-toned coloring of many.

The pony, Misty of Chincoteague, was one of these. She was startlingly marked—over her withers a white spot spread out like a map of the United States, and on her side there is a marking in the shape of a plow.

As a foal she seemed more mist than real. Her coat was a soft fusion of silver and gold, and her eyelashes were gold and wonderfully long. In contrast to her shaggy sire and dam she appeared like something from a cloud. During the sale no one dared touch her, for her wild sire glowered at people through the ambush of his forelock. And as Misty lay sleeping, her mother made fenceposts of her legs, keeping her foal safe inside them.

But after Misty’s sire was driven back to Assateague, Grandpa Beebe and his two grandchildren kept Misty for a very special purpose. She was to be the heroine of a book! They cared for her and gentled her and, true to their promise, when fall came they crated Misty and shipped her to her new owner. On a chilly rain-soaked night she arrived at her destination near Chicago, and when the crate was opened, there stood a miserable little object. Head down, tail tucked in, eyes and nose running, and so stiff-legged that even with the crate opened she only stood, snuffling and cold and afraid.

The author was torn by conflicting emotions. Where was the map on Misty’s withers? Where was the plow on her side? There were no markings at all! From head to tail she was the color of sooty snow, and woolly as a bear. That Grandpa Beebe! Had he shipped the wrong pony? And suddenly the author did not care. Here was a creature that needed help—a hot mash to eat and a warm bed and companionship. And so the little book character and her storyteller spent that stormy night in the stall together, and the little thing slept with her head cradled in human hands.

Winter passed. Spring came, and Misty rolled and rolled in the grass until her winter coat came off in great swatches for the birds to carry away. And, wonder of wonders, there was the gold coat; and there were the white markings, one in the shape of a map and the other a plow. Grandpa Beebe had sent the right pony after all!

• • •

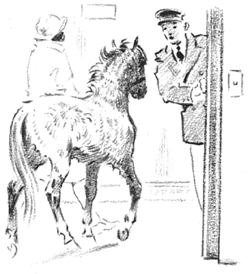

As a grown-up mare Misty continued to change color with the seasons. She forgot her wild ancestors and adopted people completely. She actually seemed to be one of them, traveling as gaily as a person, acting on television, attending a meeting with librarians, going up in elevators with them, visiting a suite in one of the fine hotels. She even refreshed herself in the wash basin, lipping the pure water so different from the brackish pools of Assateague. The librarians asked: “Can this be the same creature whose ancestors ran wild and free?”

The question caused a wondering. Was Misty unhappy? Did she long for her freedom? But, back home again, the storyteller had only to look out of her window to see Misty running to the fence to meet a group of children. As she shook hands with each one, it was plain that Misty had found her own kind of happiness—with people.

No one has ever told her she is not one of them. She wouldn’t believe it anyway.