IN AVAILABLE PHOTOS from the time, the four of us are neatly combed and smiling politely at one another. We are deeply involved in a book project to be called Bergman on Bergman. The idea was for three young journalists, armed to the teeth with detailed knowledge, to question me about my movies. The year was 1968, and I had just finished Shame.

As I leaf through that book today, I find it to be hypocritical. Hypocritical? That’s right, hypocritical. My young interviewers were the bearers of the only true political conviction. They also knew that I had been left behind by the times, demeaned and scorned by the new aesthetics of the younger generation. And yet, I could never claim there was any lack of courtesy or attentiveness on their part. What I did not realize during our sessions was that they were little by little reconstructing a dinosaur piece by piece with the kind assistance of the Monster himself. In that book, I appear less than candid, always on my guard, and quite fearful. Even questions that are only slightly provocative are given short shrift. I take pains to give answers that might arouse sympathy. I plead for an understanding that, in any case, is impossible.

One of the three, Stig Björkman, is something of an exception. Since he was a talented movie director himself, we were able to speak in concrete terms on the basis of our respective professional backgrounds. Björkman was also responsible for what is good in the book: the rich and varied selection, and exquisite montage, of pictures.

I am not saying this curious project failed through any fault of my interviewers. I had been looking forward to our encounters with childish vanity and excitement. I had imagined that I was going to open up and reveal myself in these pages, taking a well-deserved pride in my life’s work. When, too late, I became aware that they were aiming for something quite different, I became unnatural and, as I said, both fearful and worried.

As it turned out, Shame (The Shame in Great Britain) was to be followed by many more years and many more films, until I decided in 1983 to “hang up” my camera. By then I was able to view my work as a whole and began to realize that I did not mind talking about my past. People were showing genuine interest in my films, not just to be polite or in order to attack me; since I had retired, I was guaranteed harmless.

Now and then my friend Lasse Bergström and I spoke about doing a new Bergman on Bergman book — one that would be more truthful, more objective. Bergström would ask the questions, and I would talk, and that would be the only similarity to the earlier book. We kept encouraging each other to do it, and all of a sudden we found ourselves going ahead with it.

What I had not been able to anticipate was that this act of looking back would, at times, turn into a murderous and painful business. Murderous and painful give a rather violent impression, but those are the best words I can find for it.

For some reason that had never occurred to me before, I have always avoided rescreening my old movies. Whenever I have had to do so or done so out of curiosity, I have been, without exception and no matter which film it was, nervous and upset, and have felt like going out to take a leak, like running to the toilet. I have been overwhelmed with anxiety, felt like crying, been afraid, unhappy, nostalgic, sentimental, and so on. Owing to this unfortunate conjunction of tumultuous feelings, I have, understandably, tended to avoid my movies. Still, I have felt kindly toward them, even the bad ones: I know that I did my best at the time and that each was in its own way truly interesting. (Listen and you will hear how interesting it was at the time!) So I set out to stroll for a while down the pleasantly lighted corridors of memory.

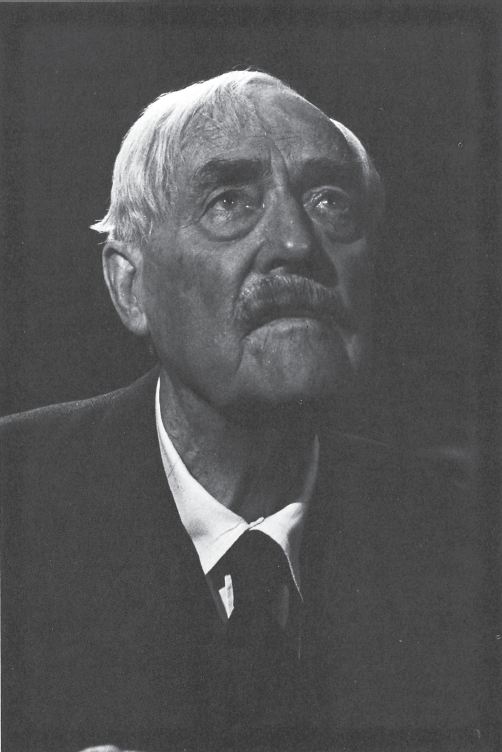

Wild Strawberries: “Victor Sjöström’s face, his eyes …”

It therefore became necessary to look at my films again, and I thought: All that happened a long time ago. Now I’ll be able to handle the emotional challenge. I’ll be able to eliminate some of my works immediately. Let Lasse Bergström look at them by himself. After all, he’s a film critic. He’s seen his share of good and bad without becoming hardened.

Watching forty years of my work over the span of one year turned out to be unexpectedly upsetting, at times unbearable. I suddenly realized that my movies had mostly been conceived in the depths of my soul, in my heart, my brain, my nerves, my sex, and not the least, in my guts. A nameless desire gave them birth. Another desire, which can perhaps be called “the joy of the craftsman,” brought them that further step where they were displayed to the world.

I would therefore have to account for their sources, their roots and origins, and remove from their files the blurred X rays of my soul. This process would be plausible with the help of my notes and workbooks, as well as those of others; of memories recalled, newspaper articles, and especially with this seventy-year-old man’s perceptive, astute, and comprehensive overview of, and objective relations to, a whole host of painful and half-suppressed experiences.

“The dreams were mainly authentic: the hearse that overturns with the coffin bursting open …”

I was going to return to my films and enter their landscapes. It was a hell of a walk.

Wild Strawberries is a good example. With Wild Strawberries as a point of departure, I can show how treacherous and tricky my “now-experience” can be. Lasse Bergström and I saw the movie one afternoon in my movie theater on Fårö (Sheep Island). It was an excellent print, and I was deeply moved by Victor Sjöström’s face, his eyes, his mouth, the frail nape of his neck with its thinning hair, his hesitant, searching voice. Yes, it was profoundly affecting! The next day we talked about the movie for hours. I reminisced about Victor Sjöström, recalling our mutual difficulties and shortcomings, but also our moments of contact and triumph.

I should add, in this connection, that my workbook for the Wild Strawberries screenplay has been lost. (I never save anything, out of superstition. Others have saved things for me.)

When later we read through the transcript of our taped conversations, we discovered that I had not said anything the least bit relevant about the way the film had been made. When I tried to recall the work process, it had totally disappeared. I only remembered — and dimly at that — that I had written the script at the Karolinska Hospital where I had been admitted for general observation and treatment. My friend Sture Helander was chief physician there, and I was given the opportunity to attend his lectures, which dealt with something as new and unusual as psychosomatic troubles. My room was small, and a writing desk had been fitted into it with some difficulty. The window faced north, and from it I could see for miles and miles.

My work year had been rather hectic; during the summer of 1956, we had made The Seventh Seal. Then I had directed three plays at the City Theater in Malmö: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Erik XIV, and Peer Gynt, the last of which premiered on March 8, 1957.

After that I spent almost two months in the hospital. The filming of Wild Strawberries began during the first part of July and finished on August 27, whereupon I returned immediately to Malmö to begin rehearsals of The Misanthrope.

I have only vague memories of that winter of 1956. And if I even try to take a few steps into that confusion, it hurts. A few fragments of a letter emerge suddenly from a lot of other letters of a very different kind. It was written by me as a New Year’s greeting and addressed to my friend Helander.

We begin to rehearse Peer Gynt after Twelfth Night; if my health were not so poor, it would be a great deal of fun. The whole troupe is in fine fettle and Max [von Sydow] will be magnificent, one can already see that. Mornings are the worst; I never wake up later than four-thirty — then my guts begin churning. At the same time my old anxieties begin, laying things waste like a blowtorch. Exactly what those anxieties are I can’t say. Perhaps I’m simply afraid of not being good enough. On Sundays and Tuesdays (the days when we don’t rehearse), I feel a lot better.

And so on. The letter was never mailed. I guess I told myself that I was whining and that my whining was meaningless. I am not overly patient with either my own or other people’s whining. The distinct advantage, as well as the disadvantage, of being the director is that you have nobody to blame but yourself. Almost everyone else has something or someone to blame. Not so with directors. They possess the unfathomable possibility of forging their own realities or fates or lives or whatever you want to call it. I have often found solace in that thought, bitter solace, and some vexation.

On closer consideration, and having taken yet another step into the dusky room of Wild Strawberries, within the camaraderie and the collective effort I find a negative chaos of human relations. The separation from my third wife was still a source of great pain. It was a strange experience to love someone with whom you could absolutely not live. My life with Bibi Andersson, a life filled with kindness and creativity, was beginning to crumble; why, I don’t remember. I was feuding bitterly with my parents. I couldn’t talk to my father and didn’t even want to. Mother and I tried time and again for a temporary reconciliation, but there were too many skeletons in our closets, too many poisonous misunderstandings. We were making the effort, since we so wanted peace between us, but we kept failing.

I imagine that one of the most impelling forces behind Wild Strawberries could be found in that situation. I tried to put myself in my father’s place and sought explanations for the bitter quarrels with my mother. I was quite sure I had been an unwanted child, growing out of a cold womb, one whose birth resulted in a crisis, both physical and psychological. Later, my mother’s diary verified this notion of mine: faced with this wretched, almost dying child, she had feelings that were decidedly ambivalent.

“… a calamitous final examination in school, the wife who fornicates in public.”

In the course of some insignificant media event, I explained that only later had I discovered what the name of the leading character — Isak Borg — really meant. Like most statements made to the media, this is the kind of untruth that fits into the series of more or less clever evasions that create an interview. Isak Borg equals me. I B equals Ice and Borg (the Swedish word for fortress). Simple and facile. I had created a figure who, on the outside, looked like my father but was me, through and through. I was then thirty-seven, cut off from all human relations. It was I who had done the cutting off, presumably as an act of self-affirmation. I was a loner, a failure, I mean a complete failure. Though successful. And clever. And orderly. And disciplined.

I was looking for my father and my mother, but I could not find them. In the final scene of Wild Strawberries there is a strong element of nostalgia and desire: Sara takes Isak Borg by the hand and leads him to a sunlit clearing in the forest. On the other side he can see his parents. They wave to him.

One thread goes through the story in multiple variations: shortcomings, poverty, emptiness, and the absence of grace. I didn’t know then, and even today I don’t know fully, how through Wild Strawberries I was pleading with my parents: see me, understand me, and — if possible — forgive me.

In that earlier book I mentioned, Bergman on Bergman, I relate in some detail an early morning trip by car to the city of Uppsala. How, following a sudden impulse, I wanted to visit my grandmother’s house at Trädgårdsgatan. How I had stood outside the kitchen door and, for a magical moment, experienced the possibility of plunging back into my childhood. That’s a lie. The truth is that I am forever living in my childhood, wandering through darkening apartments, strolling through quiet Uppsala streets, standing in front of the summer cottage and listening to the enormous double-trunk birch tree. I move with dizzying speed. Actually I am living permanently in my dream, from which I make brief forays into reality.

“Victor Sjöström was an excellent storyteller.”

In Wild Strawberries I move effortlessly and rather spontaneously between different planes — time-space, dream-reality. I cannot remember that the movement itself caused me any technical difficulties, this movement which later — in Face to Face — gave me such insurmountable problems. The dreams were mainly authentic: the hearse that overturns with the coffin bursting open, a calamitous final examination in school, the wife who fornicates in public (a scene which had already appeared in The Naked Night (Sawdust and Tinsel).

The driving force in Wild Strawberries is, therefore, a desperate attempt to justify myself to mythologically oversized parents who have turned away, an attempt that was doomed to failure. It wasn’t until many years later that my mother and father were transformed into human beings of normal proportions, and the infantile, bitter hatred was dissolved and disappeared. Then we were able to meet in a mood of affection and mutual understanding.

I had thus managed to forget why I made Wild Strawberries, and the times when I had to talk about it, I had nothing to say. It was an enigma that was slowly becoming rather interesting, at least to me.

Today I am convinced that if I forgot, if I erased all that, it had to do with Victor Sjöström. When we made the film, the age difference between us was considerable. Later on it was practically nonexistent.

“On the other side he can see his parents. They wave to him.”

From the very beginning, the artist Sjöström was overwhelming. He had made the movie that, to me, was the film of all films. I saw it for the first time when I was fifteen; to this day I see it at least once every summer, either alone or in the company of younger people. I clearly see how The Phantom Carriage has influenced my own work, right down to minute details. But that is a whole different story.

Victor Sjöström was an excellent storyteller, funny and engaging — especially if some young, beautiful woman happened to be present. We were sitting at the very source of film history, both Swedish and American. What a pity that tape recorders were not available at the time.

All these external facts are easy to recall. What I had not grasped until now was that Victor Sjöström took my text, made it his own, invested it with his own experiences: his pain, his misanthropy, his brutality, sorrow, fear, loneliness, coldness, warmth, harshness, and ennui. Borrowing my father’s form, he occupied my soul and made it all his own — there wasn’t even a crumb left over for me! He did this with the sovereign power and passion of a gargantuan personality. I had nothing to add, not even a sensible or irrational comment. Wild Strawberries was no longer my film; it was Victor Sjöström’s!

It is probably worth noting that I never for a moment thought of Sjöström when I was writing the screenplay. The suggestion came from the film’s producer, Carl Anders Dymling. And as I recall, I thought long and hard before I agreed to let him have the part.

AT FIRST I COULDN’T FIND my workbook for Hour of the Wolf, but then, suddenly, there it was. At times, the demons can be helpful. But you have to beware. Sometimes they will help you along to hell.

The notes begin on December 12, 1962. The precise moment when I finished Winter Light:

I am beginning this project in a kind of desperate enthusiasm and exhaustion. I was slated to go to Denmark to write a synopsis for a film that would have made a million. Three days and three nights of panic, with accompanying spiritual and visceral constipation. Then I gave up. There are times when self-discipline, which is a good thing, becomes self-compulsion, which is totally harmful. After having written two pages and swallowed a box of laxatives, I gave up.

I have no memory of any of this. I do remember that I once went to Denmark to write something. It is also possible that it was a synopsis based on Hjalmar Bergman’s novel The Boss, Mrs. Ingeborg, a project Ingrid Bergman was very interested in doing.*

It felt good to go home. The tension decreased, at least temporarily. The excursions into insecurity are never very creative. One thing is clear, however. I am going to work on My Shipwrecked Ones. I will, without any obligations, find out if we really have something to say to each other or if everything is due to a misunderstanding or ultimately stems from my sole desire to be in pleasant shooting locations. Actually, the whole thing began with my longing to see the ocean. Torö (Thor’s Island), to sit on a birch log and look at the waves for all eternity. Then, too, it must have been that long white sandy beach, completely unreal and yet so practical. Flat sand and the rolling ocean waves.

So I had better get to work. I know the following: The luxury liner went down in the middle of the masked ball near some group of deserted islands far out at sea. A number of people managed to swim to shore.

Everything has to be insinuated; nothing must be emphasized, nothing unraveled. The elements restrained, as in the theater. No realism. Everything has to be brilliantly clean, gentle, light, very eighteenth century, unreal, surreal, the colors never realistic.

I am on my way into some kind of comedy:

I believe that this will inevitably become an ambiguous division between wishes and dreams. Whole series of enigmatic personalities. They enter and disappear in most surprising ways, but this much is clear: He is not master of his characters. He loses them and finds them again.

Then I later wrote to myself:

Patience, patience, patience, patience, patience, don’t panic, take it easy, don’t be afraid, don’t get tired, don’t immediately feel that everything is difficult. The time is long gone when you could dash off a screenplay in three days.

But here it has begun:

Ah yes, my dear ladies, I saw a large fish, perhaps not a fish, perhaps more of an underwater elephant or perhaps a hippopotamus and a sea serpent that were copulating! I was by the Deep Place in the hollow of the mountainside where I sat, totally relaxed.

Then the Self becomes a bit more specific:

I was one of the world’s most prominent entertainment artists. As such, I went on the cruise. They had signed me on for a great deal of money. A time of calm and recovery at sea seemed to me an utterly delightful fantasy. …

But, frankly, I am reaching an age when money is no longer terribly important. I am alone now, with several marriages behind me. They have cost me a pretty penny. I have many children whom I know only superficially or not at all. My failures as a person are remarkable. Therefore, I put a lot of effort into being an excellent entertainer. I also want to mention that I am not an improvisational artist. I prepare my numbers painstakingly, almost pedantically. During my time on this island, after the shipwreck, I have jotted down several new ideas, which I hope to develop when I return to my studio.

December 27:

How goes my comedy? Oh yes, it has moved forward a little. Still the same old story about my Ghosts, friendly Ghosts, brutal, mean, joyous, stupid, unbelievably stupid, kind, hot, warm, cold, inane, anxious Ghosts. They are conspiring against me more and more, becoming mysterious, ambiguous, weird, and sometimes threatening. That’s how it goes. I get a pleasant Companion who gives me different suggestive angles and whimsies. Slowly he begins to change, however. Becomes threatening and cruel.

Hour of the Wolf is seen by some as a regression after Persona. It isn’t that simple. Persona was a breakthrough, a success that gave me the courage to keep on searching along unknown paths. For several reasons that film has become a more open affair than others, more tangible: a woman who is mute, another who speaks; therefore a conflict. Hour of the Wolf on the other hand, is more vague. There is within that film a consciously formal and thematic disintegration. When I see Hour of the Wolf today, I understand that it is about a deepseated division within me, both hidden and carefully monitored, visible in both my earlier and later work: Aman, in The Magician (The Face); Ester, in The Silence; Tomas, in Face to Face; Elisabet, in Persona; Ismael, in Fanny and Alexander. To me, Hour of the Wolf is important since it is an attempt to encircle a hard-to-locate set of problems and get inside them. I dared take a few steps, but I didn’t go the whole way.

Had I failed with Persona, I would never have dared to make Hour of the Wolf Hour of the Wolf is not a regression but an unsteady step in the right direction.

In an etching by Axel Fridell, one can see a group of grotesque cannibals ready to assault a little girl. They are all waiting for a candle in a darkening room to flicker out. A frail old man attempts to protect her. A real cannibal, dressed in a clown’s outfit, is waiting in the shadow for the candle to burn down. Everywhere in the increasing darkness, one glimpses frightening figures.

Suggested final scene: I hang myself from a beam in the ceiling, something I have actually thought of doing for some time in order to become friends with my Ghosts. They are waiting for me, right beneath my feet. There will be a festive supper — after the suicide. The double doors are thrown open. Accompanied by music (a pavane) I step inside, on the lady’s arm, and proceed to the extravagantly set table.

The Self has a mistress. She lives on the mainland but takes care of my household during the summer. She is tall and silent and serene. Together we sail across to the island; together we walk through the house; together we eat supper. During the dinner I hand her the housekeeping allowance. Suddenly she bursts out laughing. She has lost a tooth. The gap shows when she laughs, which embarrasses her. I don’t want to pretend that she is beautiful, but I like her company and we have lived together for five summers.

Winter Light represents, if you will, a moral victory and a departure. I have always been embarrassed by my need to please. My love for the audience has been rather complicated, with strong elements of my fear of not being liked. In my artistic self-solace has also been included a wish to give solace to my audience. Wait a minute! It isn’t as bad as all that! My fear of losing some kind of power over people … my legitimate fear of losing my livelihood. The only thing is, sometimes one feels a compelling need to shoot blanks, to leave all the ingratiating stuff behind. At the risk of being forced into double compromises at some later date (the film industry is not especially considerate of its anarchists), it sometimes feels liberating to stand up and, without a gesture of apology or amiability, display an agonizingly human situation. The punishment would certainly be swift and sure. I still have the painful memory of the reception of Sawdust and Tinsel, my first attempt in that genre.

The departure is also one of theme. With Winter Light I dismiss the religious debate and render an account of the result. Perhaps it is of less importance to the viewers than to me. The film is the tombstone over a traumatic conflict, which ran like an inflamed nerve throughout my conscious life. The images of God are shattered without my perception of Man as the bearer of a holy purpose being obliterated. The surgery has finally been completed.

“The Cannibals” are waiting: Axel Fridell’s etching (“The Old Curiosity Shop”/Little Dorrit) and a scene from Hour of the Wolf.

These notes were written in 1962, sometime during the Christmas season. Then I heard nothing from my cannibals of Hour of the Wolf for almost two years.

When the Royal Dramatic Theater closed for the season on June 15, 1964, I realized I was completely exhausted. By then The Silence had opened and the people from whom my wife Käbi and I used to rent a house on Ornö Island did not want us anymore. They were of the opinion that nice tenants should not make obscene films. We had looked forward to a summer on the island — Käbi had worked very hard as well — to our arrival at that quiet, isolated place, which you can only reach by boat. Now we would have to remain in Djursholm the whole summer, and that was not a pleasant prospect. It was a horribly hot summer, and I settled into the guest room, which faced north and was somewhat cooler.

Ivar Lo-Johansson speaks about “the milkmaids’ white whip.” The white whip for those who manage theaters is to be forever reading plays. If we put on twenty-two plays during a season, that represents perhaps 10 percent of what the theater’s managing director reads. To liberate myself from the various projects that endlessly filled my mind and from any thoughts about the upcoming theater season, I set about writing a screenplay, surrounding myself with music and silence, which awakened mutual aggressions between Käbi and me, since she was practicing on the grand piano in the living room. It developed into a sophisticated, acoustic terrorism. Sometimes I drove to Dalarö, where I sat on a cliff, gasping, looking out over the bay.

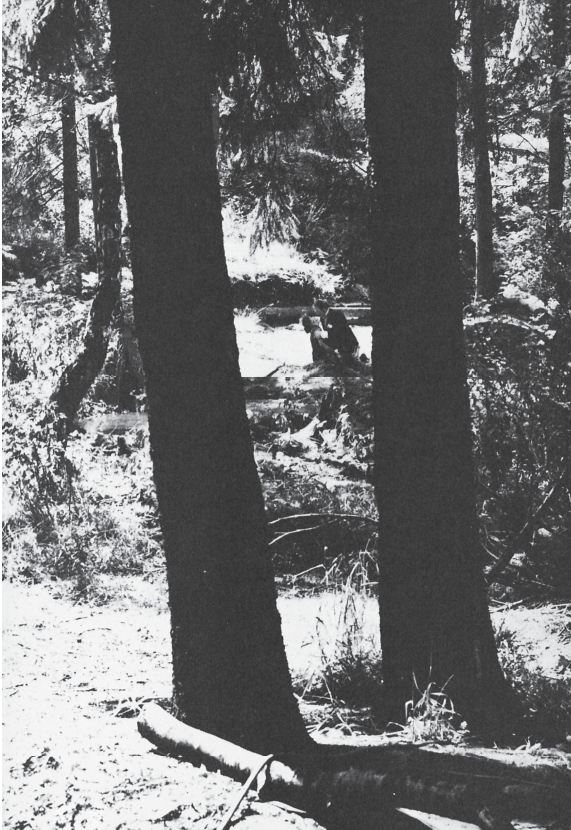

From the episode with Johan (Max von Sydow) and the small demon (Mikael Rundquist) in Hour of the Wolf.

In that mood the writing of The Cannibals began:

Like a dispirited angleworm, I pull myself out of the easy chair and go over to my worktable to try and write. I feel awkward and find the work repugnant. The table shivers and shakes with every damn letter I write. I have to change tables. Perhaps it would be better to stay in my easy chair, with a pillow on my lap. It’s better, but it still isn’t good. My pen is no damn good either. But the room is reasonably cool. I think I’ll stay in the guest room after all. A summary: The story is about Alma. She is twenty-eight years old and has no children.

That’s how the story about The Cannibals begins. I have turned the perspective around, so that all is seen from Alma’s point of view.

If all this ends up being nothing but a game, delineated during a solemn study of one’s reflection in a mirror, with a lot of uncalled-for vanity on the one hand, and a vague interest on the other, then it is meaningless. It is perfectly possible that it’s meaningless anyway.

It is safe to say that it’s no longer a comedy.

Exhaustion does not mean that you simplify but that you complicate; you sink your teeth into something and do too much. Every spare battery is connected and the revolutions are accelerated; the critical judgment is weakened; and the wrong decisions are made, since you are unable to make the right ones.

In Hour of the Wolf there is no trace of that exhaustion. And yet the film was made during the strenuous period when I was head of the Royal Dramatic Theater. The dialogue is crisp, a trifle too literary but not overly so.

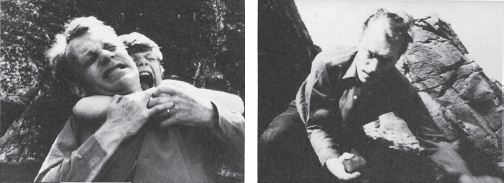

For a moment I want to go back to the erotic theme; I am referring to a scene I think is well executed, namely, when Johan kills the little demon who has bitten him.

There is only one error: the demon should have been naked! And to take it one step farther: Johan should have been naked as well.

I was vaguely aware of this error while we were filming that scene, but I didn’t have the strength or the courage to suggest it to Max von Sydow, the actor who played Johan. Had both actors been nude, the scene would have been brutally clear. When the demon clings to Johan’s back, trying to bite him, he is crushed against the mountainside with orgasmic force.

Then: Why is Lindhorst* putting makeup on Johan before Johan goes to the love tryst with Veronica Vogler? From the beginning it is clear to us that their passion is a passion without emotion, an erotic obsession. We understand that in the very first scene. Later Alma reads from Johan’s diary, from which one understands that his liaison with Veronica was a disaster.

Lindhorst’s makeup transforms Johan into a mixture of clown and woman, and then he dresses him in a silk gown, which makes him even more feminine. The white clowns have a multiple, ambiguous symbolism: they are beautiful, cruel, dangerous, balancing on the border between death and destructive sexuality.

The demons in Hour of the Wolf. Gertrud Fridh with Max von Sydow. Ulf Johanson in the foreground. Naima Wifstrand. Ingrid Thulin as Veronica Vogler with Johan (Max von Sydow) in makeup.

The pregnant Alma represents that which is living, precisely as Johan describes it: “If I patiently sketched you day after day …”

There is no doubt that the demons, in a joking, decisive, and terrible manner, are separating Johan from Alma.

When Johan and Alma walk home from the castle in the windy dawn, she says: “No, I’m not going to run away from you, however afraid I may be. And one thing more: They want to separate us. They want to keep you to themselves, but if I’m with you, it will be much more difficult. They are not going to make me run away from you, however hard they try. I’ll stay, I will. I’ll stay as long as I …”

Then the fatal weapon is put between them, and Johan makes his choice. He chooses the dream of the demons instead of the palpable reality of Alma. Here I was setting forth on a problematic path that can ultimately be reached only through poetry or music.

There is no doubt that my upbringing was a fertile ground for the demons of neurosis.

I tried to clarify this point in The Magic Lantern.

Most of our upbringing was based on such concepts as sin, confession, punishment, forgiveness, and grace, concrete factors in relationships between children and parents, between God and ourselves. There was an innate logic in all this, which we accepted and thought we understood.

So punishment was something self-evident, never questioned. It could be swift and simple, a slap in the face or a smack on the bottom, but could also be utterly sophisticated, refined through generations.

Major crimes reaped exemplary punishment: starting the moment the crime was discovered. The criminal confessed to a lower authority, that is, to the maids or Mother or one of the innumerable female relations living at our parsonage on various occasions.

The immediate consequence of confessing was that you were frozen out. No one spoke or replied to you. As far as I can make out, the idea was to make the criminal long for punishment and forgiveness. After dinner and coffee, the parties were summoned to Father’s room, where interrogation and confessions were renewed. After that, the carpet beater was brought in, and you yourself had to declare how many blows you felt you deserved. When the punishment quota had been established, a hard, green cushion was fetched, trousers and underpants pulled down, you prostrated yourself over the cushion, someone held firmly onto your neck, and the blows were administered.

I can’t claim that it hurt all that much. The ritual and the humiliation were most painful. My brother got the worst of it. Mother used to sit by his bed, bathing his back where the carpet beater had loosened the skin and streaked his back with bloody weals.

After the blows had been administered, you had to kiss Father’s hand, at which point forgiveness was declared and your burden of sin fell away, being replaced by deliverance and grace. Though of course you had to go to bed without supper and evening reading, the relief was nevertheless considerable.

There was also a spontaneous kind of punishment that could be terrifying for a child who was afraid of the dark: being locked in a special closet for various lengths of time. Alma in the kitchen had told us that in that closet lived a small creature that ate the toes of naughty children. I quite clearly heard something moving in there in the dark, and my terror was total. I don’t remember what I did, probably climbed onto shelves or hung from hooks to avoid having my toes thus devoured.

All this comes back in Fanny and Alexander. But by then I had reentered the light of day and was able to depict it without a tremor of the hand, without being personally involved.

In Fanny and Alexander I could also do it with pleasure. In Hour of the Wolf there is neither distance nor objectivity. I simply experimented in a way that may be vital, but the spear was thrown randomly into the darkness. And the path of the spear is imprecise.

Earlier I was quick to downgrade Hour of the Wolf, probably because it did touch on so many suppressed aspects of my personality. While Persona possesses an intense light, an uninterrupted focus, Hour of the Wolf takes place in a land of twilight and also exploits elements that are new to me — romantic irony, ghosts — elements that the film plays with. I still find it funny when the baron without any difficulty rises to the ceiling and says, “Don’t pay any attention to this; it’s only because I’m jealous.” I also feel a quiet joy when the old woman takes off her face and remarks, “Now I can hear the music better.” After which she puts her eye into her glass of sherry.

During supper at the castle, the demons look normal, though somewhat incongruous. They stroll in the park; they converse; they put on the marionette theater performance. Everything is rather peaceful.

With Max von Sydow and Naima Wifstrand in the nighttime forest of Hour of the Wolf.

With Max von Sydow and Naima Wifstrand in the nighttime forest of Hour of the Wolf.

But they are living the life of the doomed, in unbearable torment, eternally entangled in one another. They bite each other and eat each other’s souls.

Their suffering is eased for a brief period: when The Magic Flute is performed in the small marionette theater. The music brings momentary peace and solace.

The camera moves over everyone’s face. The rhythm of the text is a code: Pa-mi-na means Love. Does Love still live? Pamina lebet noch; Love still lives. The camera on Liv [Ullman]: a double declaration of love. At that time Liv was carrying our daughter, Linn. Linn was born the very day we filmed Tamino’s entrance into the palace court.

Johan appears, transformed into a weirdly androgynous creature, and Veronica lies naked and allegedly dead on an autopsy table. He touches her in an endless gesture. She awakens, laughs, and begins to kiss him with small bites. The demons, who have been waiting for this moment, greatly appreciate the scene. One glimpses them in the background; they are sitting and lying on top of one another; a few have climbed up to the window and the ceiling. Then Johan says, “I thank you, the mirror is shattered, but what do the fragments reflect?”

I could not give an answer. Exactly the same words are said by Peter in From the Life of the Marionettes. When in his dream he discovers his wife lying murdered, he says, “The mirror is broken, but what do the fragments reflect?”

I still don’t have a good answer.

“Their suffering is eased for a brief period: when The Magic Flute is performed in the small marionette theater.”

I BELIEVE THAT Persona is to a great degree connected to my activities as head of the Royal Dramatic Theater. That experience was like a blowtorch, forcing a kind of accelerated ripening and maturing. It clarified and solidified my relation to my profession in a brutal and unequivocal manner.

I had just finished The Silence, which lived on its own strength and vitality. The fact that immediately afterward I began shooting All These Women (Now About These Women) was a mark of my loyalty to the studio, Svensk Filmindustri. It was also further proof of my deplorable inability to hit the brakes when I ought to.

I was named managing director of the Royal Dramatic Theater at Christmas 1962. I should have immediately informed Svensk Filmindustri that we would have to shelve all film plans for the moment. But unfortunately, I felt it wasn’t reasonable or possible to postpone making a film that had been so long in preparation.

With my death-defying optimism and incomprehensible love of work, I informed both the minister of education, who had presented me with the offer to head the national theater, and myself: That’s fine. I can handle this.

On January 1, 1963, I became the newly appointed head of a theater in an advanced state of disintegration. There was no repertoire, no contracts with the actors for the upcoming season. Organization and administration were sadly lacking. The reconstruction of the theater building itself, which had moved forward in fits and starts, had been stopped altogether owing to lack of money. I found myself in an insoluble and incomprehensibly chaotic situation.

I soon found out that my duties were not limited to raising the artistic pulse and seeing to it that people came to the performances. It was a question of reorganizing the whole company from the bottom up.

No question: the work captivated me. The first year was strangely enjoyable. We had a great deal of luck. The red lights, proclaiming sold-out performances, were switched on, and the attendance figures soared. I was even able to cover the losses of the two superfiascos with which the season ended. The next year, during the same week in June, I opened Harry Martinson’s Three Knives from Wei at the theater and premiered the film All These Women.

I returned to the Royal Dramatic Theater in the fall of 1964, and that year had two solid successes. I directed Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler with Gertrud Fridh, and Molière’s Don Juan. But the opposition had grown both inside and outside the theater. Toward the end of the season, the theater ensemble undertook a horrible trip to the inauguration of a new theater in the city of Örebros. People died or fell seriously ill. I myself had a fever of 102, despite which I went on the trip, ending up with double pneumonia and acute penicillin poisoning.

I was exhausted, but I tried to manage the theater anyway. Finally, in April, I was admitted to Sophiahemmet, the royal hospital, for proper care. And I began to write Persona, mainly to keep my hand in the creative process.

By that time, The Cannibals project had been canceled. Both Svensk Filmindustri and I saw how unrealistic it would be to try to direct such a major production during the summer. That meant there was a hole in the planned production for the year; one film was missing.

That’s when I said, “Let’s not give up hope. I’ll try to make a movie after all. Possibly nothing will come out of it, but at least we can give it a try!”

Thus it was that in April of 1965 I began to take some notes, in the aftermath of my mishandled pneumonia, but this writing was also a result of the stink bomb attacks to which I had been subjected in the executive office of the theater. I was beginning to ask myself: Why am I doing this? Why do I care so much? Is the role of the theater finished? Has the mission of the art been taken over by other forces?

I had good reasons for thinking such thoughts.

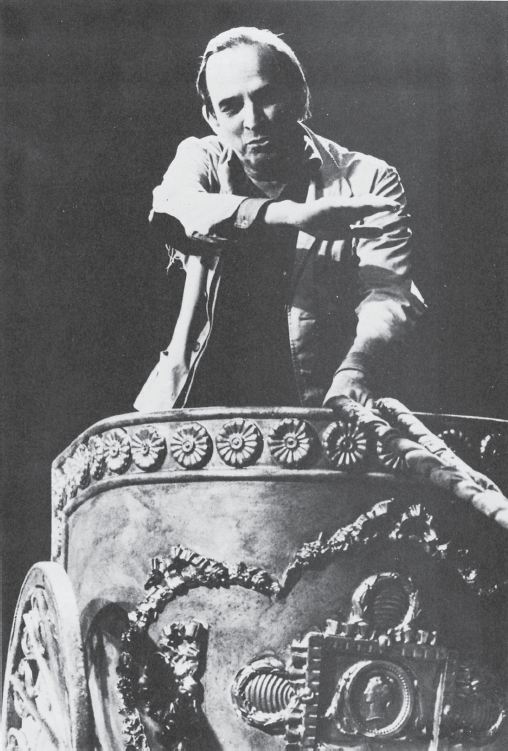

It was not a case of developing an aversion to my professional life. Although I am a neurotic person, my relation to my profession has always been astonishingly non-neurotic. I have always had the ability to attach my demons to my chariot. And they have been forced to make themselves useful. At the same time they have still managed to keep on tormenting and embarrassing me in my private life. The owner of the flea circus, as you might be aware, has a habit of letting his artists suck his blood.

So I was convalescing at Sophiahemmet. Slowly I began to realize that my activities as director of Sweden’s national theater were hindering my creativity. I had driven all my engines at top speed, and the engines had shaken the old body till it fell apart. So now it was necessary for me to write something that would dissipate the feeling of emptiness, of going nowhere. My emotional state was expressed quite clearly in an essay I wrote when I received the Dutch Erasmus Prize. I entitled it “The Snakeskin” and published it as a preface to Persona:

Artistic creativity in me has always manifested itself as hunger. With quiet satisfaction I have acknowledged this need, but I have never in my whole conscious life asked myself where this hunger has come from and why it kept demanding satisfaction. During these last few years, as the hunger begins to abate, I feel a certain urgency to seek out the very reason for my activity.

“I have always had the ability to attach my demons to my chariot” (from the filming of The Magic Flute).

A very early childhood memory is my strong need to show off whatever I have accomplished; skill in drawing, the art of hitting a ball against a wall, my first strokes when I learned how to swim.

I remember that I had a strong desire to draw the adults’ attention to these manifestations of my presence in the world. I felt that my fellow beings never paid enough attention to me. When reality no longer was enough, I began to fantasize, to regale my contemporaries with wild stories about my secret exploits. Those were embarrassing lies, which without fail broke into pieces against the surrounding world’s sober skepticism. Finally I pulled out of the fellowship and kept my dream world to myself. A contact-seeking and fantasy-obsessed child had been rather quickly transformed into a wounded and sly daydreamer.

But a daydreamer is not an artist except in his dreams.

It was obvious that cinematography would have to become my means of expression. There I made myself understood through the language that I lacked, through music I had not mastered, and through painting which left me cold. Suddenly I had an opportunity to communicate with the world around me in a language that literally is spoken from soul to soul in expressions that, almost sensuously, escape the restrictive control of the intellect.

With all the pent-up hunger of the child I was, I threw myself at my chosen medium and for twenty years I have tirelessly, and in a kind of frenzy, supplied dreams, sense experiences, fantasies, insane outbursts, neuroses, cramped faith, and pure unadulterated lies. My hunger has endlessly renewed itself. Money, fame, and success have been surprising, but basically indifferent, consequences of my rampage. Having said that, I am in no way downgrading or negating what I have possibly accomplished. Art as self-satisfaction obviously has its value, especially to the artist.

So if I want to be completely honest, art (not just the art of the cinema) is for me unimportant.

Literature, painting, music, film, and theater give birth to and feed upon themselves. New mutations, new combinations occur and are destroyed; viewed from the outside the movement seems feverishly vital, nourished by the artists’ unbridled eagerness to project to themselves and to a more and more distracted audience a world that has ceased to ask what they think. There are a few isolated places where the artists are punished, the arts themselves are considered risky and deserving of being suffocated or guided. Generally speaking, however, art is free, shameless, irresponsible, and as I said: its constant movement is intense, almost feverish; it resembles, in my opinion, a snake’s skin full of ants. The snake is long since dead, emptied, deprived of its poison, but the skin moves, full of bustling life.

I hope and believe that others have a more balanced and allegedly objective opinion. If I raise all these tedious matters and if despite all I’ve said I claim I still want to create art, there is a very simple reason (putting aside all the purely material motivations).

The reason is curiosity. A limitless, never satisfied, ever renewed, unbearable curiosity, drives me forward, never leaves me in peace; it has completely replaced my hunger for contact and fellowship of earlier times.

I feel like a prisoner who, after a long detention, suddenly stumbles out into the hurly-burly of life. I am in the grip of an uncontrollable curiosity. I note, I observe, I look everywhere; everything is unreal, fantastic, frightening, or ridiculous. I catch a speck of dust floating in the air; maybe it’s the germ of a film — what does it matter? It doesn’t matter, but I find it interesting, therefore I insist that it is a film. I come and go with this object that belongs to me, and I care for it with joy or sorrow. I push and am pushed by other ants; we are doing a colossal piece of work. The snakeskin moves. This, and only this, is my truth. I don’t ask that it be true for anybody else, and as solace for eternity it’s obviously rather slim pickings, but as a foundation for artistic activity for a few more years it is in fact enough, at least for me.

To be an artist for one’s own sake is not always pleasant. But it has one enormous advantage: the artist shares his condition with every other living being who also exists solely for his own sake. When all is said and done, we doubtless constitute a fairly large brotherhood, which thus exists within a selfish community on our warm and dirty earth, beneath a cold and empty sky.

“The Snakeskin” was written in direct connection with the work on Persona. This can be illustrated by a note from April 29 in the workbook:

Persona: Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann) and her nurse, Alma (Bibi Andersson).

Persona: Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann) and her nurse, Alma (Bibi Andersson).

I will attempt to keep the following commands:

Breakfast at half past seven with the other patients.

Thereafter immediately get up and take a morning walk.

No newspapers or magazines during the aforementioned time.

No contact with the theater.

Refuse to receive letters, telegrams, or telephone calls.

Visits to home allowed during the evening.

I feel that the final battle is fast approaching. I must not postpone it further. I must arrive at some form of clarity. Otherwise Bergman will definitely go to hell.

It is clear from this passage that the crisis runs deep. I laid down for myself the same commandments when, later, I was trying to get back on my feet following the whole affair about my taxes.* Punctiliousness then became my way of surviving.

From this crisis, Persona was born and grew:

With Sven Nykvist.

So she has been an actress — one may give her that? Then she fell silent. Nothing remarkable about that.

I’ll have to start with a scene in which the doctor tells nurse Alma what has taken place. That first scene is all-important. The patient and the person caring for her grow close together, like nerves and flesh. The only thing is, she refuses to speak. In fact, she doesn’t want to lie.

This is one of the first notes in my workbook, dated April 12. Something else is also written there, something I did not act upon but which still has to do with Persona, especially with the title. “When nurse Alma’s fiancé visits her, she hears for the first time how he speaks. She notes how he touches her. She becomes frightened, since she sees that he behaves as if he were acting a part.”

When you bleed, you feel bad, and then you don’t act.

It was an extremely difficult period of my life. I had a feeling that a threat was hanging over my head:

Could one make this into an inner happening? I mean, suggest that it is a composition for different voices in the same soul’s concerto grosso? Anyhow, the time and space factors must be of secondary significance. One second must be able to stretch itself out over a long period of time and contain a handful of lines strewn without any apparent connection.

This problem is evident in the completed film. The actors move in and out of rooms without transfer distances. Whenever suitable, an occurrence is prolonged or shortened. The conception of time is suspended.

Then a note follows that goes far back into my childhood:

I imagine a white, washed-out strip of film. It runs through the projector and gradually there are words on the sound tape (which perhaps runs beside the film strip itself). Gradually the precise word I’m looking for comes into focus. Then a face you can barely make out dissolves in all that whiteness. That’s Alma’s face. Mrs. Vogler’s face.

When I was a boy, there was a toy store where you could buy used film. It cost five ore [about one penny] a yard. I put thirty or forty yards of the film into a strong soda solution and let the pieces soak for half an hour. The emulsion dissolved and the layer of images disappeared. The strips of film became white, innocent, transparent. Pictureless.

With different colored india inks I could now draw new pictures. When Norman McLaren’s directly drawn films appeared after the war, it was no news to me. The strip of film that rushes through the projector and explodes in pictures and brief sequences was something I had carried around with me for a long time.

Throughout most of the month of May I still had attacks of fever:

All this weird fever and all these solitary reflections. I have never had it so good, and so bad. I believe that if I really tried, I might perhaps attain something unique, something I had been unable to reach earlier. A transformation of the themes. Something simply happens and without anyone asking how it happens.

Alma is learning to know herself. Through Mrs. Vogler, nurse Alma is off in search of herself.

Alma tells a long, totally banal story about her life and her great love for a married man, about her abortion and about Karl Henrik whom she really doesn’t love, and who was a disappointment in bed. Then she drinks some wine, lets herself go, starts crying, and sobs in Mrs. Vogler’s arms.

Mrs. Vogler is full of sympathy. The scene goes on from morning to noon, from evening to night, and on to morning. And Alma is becoming increasingly attached to Mrs. Vogler.

I think it’s a good thing that at this point different documents exist, for instance, the letter from Mrs. Vogler to Dr. Lindkvist. Which is filled with light-hearted banter but also contains, on a humorous note, a funny but harsh portrait of nurse Alma’s character.

I pretend that I’m an adult. I am constantly astonished that people take me seriously. I say: I want this and I would like that. … They listen respectfully to my points of view, and often they do what I tell them. Or even praise me for being right. As for me, I never think that all these people are children who act at being adults. The only difference is that they have forgotten or never think about the fact that they are actually children.

My parents spoke of piety, of love, and of humility. I have really tried hard. But as long as there was a God in my world, I couldn’t even get close to my goals. My humility was not humble enough. My love remained nonetheless far less than the love of Christ or of the saints or even my own mother’s love. And my piety was forever poisoned by grave doubts. Now that God is gone, I feel that all this is mine; piety toward life, humility before my meaningless fate, and love for the other children who are afraid, who are ill, who are cruel.

From the filming of Persona: Liv Ullmann, Bibi Andersson, and Sven Nykvist.

The following was written on Ornö in May. I am getting close to the gist and core of both Persona and “The Snake-skin”:

Mrs. Vogler desires the truth. She has looked for it everywhere, and sometimes she seems to have found something to hold on to, something lasting, but then suddenly the ground has given way under her feet. The truth had dissolved and disappeared or had, in the worst case, turned into a lie.

My art cannot melt, transform, or forget: the boy in the photo with his hands in the air or the man who set himself on fire to bear witness to his faith.

I am unable to grasp the large catastrophes. They leave my heart untouched. At most I can read about such atrocities with a kind of greed — a pornography of horror. But I shall never rid myself of those images. Images that turn my art into a bag of tricks, into something indifferent, meaningless. The question is whether art has any possibility of surviving except as an alternative to other leisure activities: these inflections, these circus tricks, all this nonsense, this puffed-up self-satisfaction. If in spite of this I continue my work as an artist, I will no longer do it as an escape or as an adult game but in the full awareness that I am working within an accepted convention that, on a few rare occasions, can give me and my fellow beings a few seconds of solace or reflection. The main task of my profession is, when all is said and done, to support me, and, as long as nobody seriously questions this fact, I shall continue, by a pure survival instinct, to keep working.

The outer world intrudes on Elisabet Vogler in her sickroom.

“Then I felt that every inflection of my voice, every word in my mouth, was a lie, a play whose sole purpose was to cover emptiness and boredom. There was only one way I could avoid a state of despair and a breakdown. To be silent. And to reach behind the silence for clarity or at least try to collect the resources that might still be available to me.”

Here, in the diary of Mrs. Vogler, lies the foundation of Persona. These were new thoughts to me. I had never foreseen that my activities had a direct relation to society or to the world. The Magician — with another silent Vogler in the center — is a playful approach to the question, nothing more.

On the final pages in the workbook appears the decisive variation:

After the major confrontation, it is evening, then night. When Alma falls asleep or is on the verge of falling asleep, it is as if someone were moving in the room, as if the fog had entered and made her numb, as if some cosmic anxiety had overwhelmed her, and she drags herself out of bed to vomit, but can’t, and she goes back to bed. Then she sees that the door to Mrs. Vogler’s bedroom is partly open. She enters and finds Mrs. Vogler unconscious or seemingly dead. She is frightened and grabs the telephone, but there is no dial tone. She returns to the dead woman, glancing slyly at her, and suddenly they exchange personalities. This way, exactly how I don’t know, she experiences, with a fragmentary sharpness, the condition of the other woman’s soul, to the point of absurdity. She meets Mrs. Vogler, who now is Alma and who speaks with her voice. They sit across from each other, they speak to each other with inflections of voice and gestures, they insult, they torment, they hurt one another, they laugh and play. It is a mirror scene.

The confrontation is a monologue that has been doubled. The monologue comes, so to speak, from two directions, first from Elisabet Vogler, then from nurse Alma.

Sven Nykvist and I had originally planned a conventional type of lighting on Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson. But it didn’t work. We then agreed to keep half of their faces in complete darkness — there wouldn’t even be any leveling light.

From there on it was a natural evolution, in the final part of the monologue, to combine the two illuminated halves of their faces, to let them float together to become one face.

In most people one side of the face is more attractive than the other, their so-called good side. The half-illuminated images of Liv’s and Bibi’s faces that we combined into one showed their respective bad sides.

When I received the double-copied film from the laboratory, I asked Liv and Bibi to come to the editing room.

Bibi exclaims in surprise: “But Liv, you look so strange!” And Liv says: “No, it’s you, Bibi, you look very strange!” Spontaneously they denied their own less-than-good facial half.

The screenplay for Persona does not look like a regular scenario.

When you write a scenario, you are anticipating the technical challenges as well. You are, so to speak, writing the score. Then all you have to do is put the music on the stands and let the orchestra play.

I cannot arrive at the soundstage or the exterior location and assume that “things will fall into place one way or another.” You cannot improvise on an improvisation. I dare to improvise only if I know that I will be able to go back to a carefully constructed plan. I cannot trust that inspiration will strike when I get to the set.

“From there on it was a natural evolution, in the final part of the monologue, to combine the two illuminated halves of their faces, to let them float together to become one face.”

When you read the script of Persona, it may look like an improvisation, but it is painstakingly planned. Nonetheless I have never shot as many retakes during the making of any other film. When I say retakes I do not mean repeated takes of the same scene the same day. I mean retakes that are a consequence of my seeing the previous day’s rushes and not being satisfied with what I saw.

We began filming in Stockholm and got off to a bad start.

But, slowly and squeakingly, we cranked it out. Suddenly I enjoyed saying: “No, let’s do it better, let’s do it this way or that, and here we could do it a bit differently.” Nobody ever became upset. Half the battle is won when nobody starts feeling guilty. The movie also naturally profited from the strong personal feelings that emerged during the filming. It was in short a happy set. In spite of the grueling work, I had a feeling that I was working with complete freedom both with the camera and with my collaborators, who followed my every twist and turn.

When I returned to the Royal Dramatic Theater in the fall, it was like going back to the slave galley. What a difference between the meaningless, stressful administrative work at the theater and the freedom I had experienced filming Persona! At some time or other, I said that Persona saved my life — that is no exaggeration. If I had not found the strength to make that film, I would probably have been all washed up. One significant point: for the first time I did not care in the least whether the result would be a commercial success. The gospel according to which one must be comprehensible at all costs, one that had been dinned into me ever since I worked as the lowliest manuscript slave at Svensk Filmindustri, could finally go to hell (which is where it belongs!).

Today I feel that in Persona — and later in Cries and Whispers — I had gone as far as I could go. And that in these two instances, when working in total freedom, I touched wordless secrets that only the cinema can discover.

I WRITE IN The Magic Lantern:

Face to Face was intended as a film about dreams and reality. The dreams were to become tangible reality. Reality would dissolve and become dream. I have occasionally managed to move unhindered between dream and reality: Wild Strawberries, Persona, The Silence, Cries and Whispers. This time it was more difficult. My intentions required an inspiration which failed me. The dream sequences became synthetic, the reality blurred. There are a few solid scenes here and there, and Liv Ullmann struggled like a lioness. Her strength and talent held the film together. But even she could not save the culmination, the primal scream, which amounted to an enthusiastic but ill-digested fruit of my reading. Artistic license sneered through the thinly woven fabric.

But the case of Face to Face is more complicated than that. In The Magic Lantern, I dismiss it briefly and lightly. Earlier on I simply dismissed it or declared it an idiot. That in itself is slightly suspicious.

Now I see it like this: From the beginning and up to the main character’s attempted suicide, Face to Face is perfectly acceptable. The story is clearly told, though rather compressed. There are no real weaknesses in the material itself. If the second part had maintained the same level as the first, the film would have been saved.

My workbook, dated April 13, 1974:

So now I have completed The Merry Widow. It was with great relief that I dismissed the troublesome lady (Streisand). I have also said good-bye to the film about Jesus. Too long, too many togas, too many quotations. What I long for now is to walk along my own path. At the theater I always follow others’ paths; when it comes to my films I want to be myself.

This is a feeling that grows stronger and stronger. As is the desire to force my way into the secrets beyond the walls of reality. To find a maximum expression with a minimum of external gestures. And yet, on this subject I have to say something that I must tell myself is extremely important: I do not want to follow beaten paths. I still maintain that in the context of that technique Cries and Whispers goes as far as one can go.

I also write that I look forward to the filming of The Magic Flute, which is imminent. “Let’s see if I feel the same way in July”

Technically speaking, there is the pleasant notion of constructing a single, strange room in the studio at Dämba and thus, through varying transformations of the human beings who are moving within it, depict the past. And there is also the secret person behind the tapestry in the other room. The person who affects what happens as well as what does not happen. The one who is there and yet is not!

That thought had haunted me for a long time: Behind the wall or the tapestry would be a powerful, hermaphroditic creature, controlling whatever was happening in the magic room.

At that time the small soundstage at Damba, where we had filmed Scenes from a Marriage, still existed. It was pleasant and practical. We lived and worked on Fårö Island. The process of minimizing, of simplifying, has always been stimulating to me. So I imagined that we would shape the film within the very limited confines of the soundstage.

After that, nothing is written in my workbook until July 1:

So now the filming of The Magic Flute is finished. It has been a remarkable period of my life. This joy, this proximity to the music every day! All the affection and tenderness I encountered.

It was almost so that I did not notice how heavy and complicated it had become: except for the fact that I kept getting colds, yes, it has become a real neurosis. It has cast a shadow over my existence, and there were times when I thought I wasn’t completely sane.

Back at Fåöro I began cautiously to outline Face to Face:

She has sent the children abroad. The husband is on a business trip. The house they live in is being remodeled. So she moves into her parents’ apartment on Strandvägen, beyond the Djurgårds Bridge, near the Oscar Church. She thinks she’ll be here for some time and get a lot of work done. Our heroine is especially looking forward to being by herself in the summer city and to thinking about herself and her own work without distraction.

The danger of not feeling loved, the fear that comes with the insight that one is not loved, the pain in not being loved, the attempt to forget that one is not loved.

Then some time goes by. This is written more or less in mid-August:

What if one turned the picture upside down? The dreams are reality, the reality of the days’ events the unreal: the silence of a summer day in the streets around Karla Square. Sunday, with its desolate ringing of church bells, the twilight hours, filled with morbid longings, slightly feverish. And then the light in the large, empty apartment.

Here it begins to come together:

Seven dreams with small islands of reality! The distance between body and soul, the body being something alien. Keeping body and emotions separate. The dream of humility, the erotic dream, the melancholy dream, the horror dream, the funny dream, the annihilation dream, the dream of the mother.

Then I suddenly imagine the whole thing as a masquerade. On September 25 I write:

Hesitation and confusion greater than ever — or have I simply forgotten how it usually is? A lot of irrelevant viewpoints obviously mingle with my reasoning, views that I don’t even want to think about since I find them so embarrassing.

Slowly I begin to understand that thanks to this film, and a screenplay that offers me stubborn resistance, I am trying to reach certain complications within myself. My reluctance when it comes to Face to Face probably stems, at least superficially, from the fact that I am touching on a number of my own inner conflicts without reaching or unmasking them. But at the same time I have sold out something important and have failed. Painfully, I was moving in on it. I have made a gigantic effort to bring something complicated into the light of day. It’s one thing to work on a screenplay. It takes place between yourself, your pen, your piece of paper, and a span of time. It’s an entirely different matter when you stand there in front of the whole immense machinery.

Suddenly the film as it ought to have been emerges from my workbook:

She sits on the floor in her grandmother’s apartment, and the statue moves in the sunshine. On the stairs she meets a large dog that bares its teeth. Then her husband arrives. He is dressed as a woman. She goes looking for a doctor. She is a psychiatrist herself and says that “she doesn’t understand this particular dream in spite of having understood everything that has happened to her over these last thirty years.” Then the old lady raises herself from her enormous, dirty bed and looks at her with her one, ailing eye. But grandmother and grandfather hug each other, and grandmother caresses grandfather’s cheeks and whispers tender words to him in spite of his not being able to utter more than a few isolated syllables.

But behind all this, behind the drapes, a whispered conversation is carried on about what ought to be done with her sexually, perhaps a widening of her anal opening. And at the same moment She appears, the Other, who takes such things lightly and caresses her in all sorts of ways. It is unexpectedly pleasant. But now somebody arrives and asks for her help, really pleads with her, somebody in a desperate situation. She throws a tantrum, followed by an anxiety attack, because the tension is not lessening. But, in spite of everything, it’s a relief to plan and carry out that murder of Maria she has been thinking about for so long. Although afterward it will be even more difficult to find someone who will care for me and tell me not to be afraid. And if I change my clothes completely and go to a party, everybody must see and understand that I am innocent and cast their suspicions on somebody else.

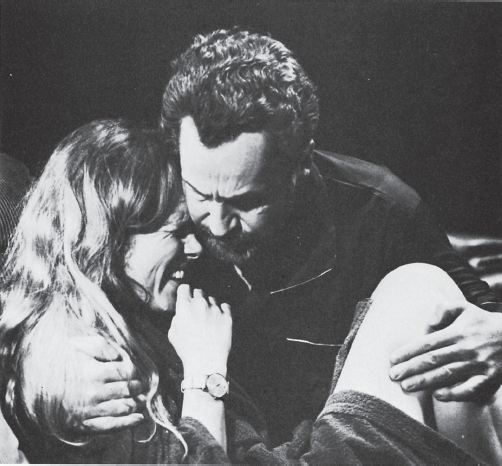

Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson in Face to Face.

But in the room with the candelabras everybody is masked, and suddenly they begin to dance a dance she doesn’t know, a pavane.

Somebody says that several of those who are dancing are dead and have come to honor the festivities with their presence. The tabletop is black and shiny. She leans her breasts against the top of the table and sinks slowly downward as somebody licks her whole body, especially between her legs. It doesn’t distress her but on the contrary fills her with a feeling of pleasure. She laughs, and a dark-haired girl with large red hands lies down on top of her. Beautiful music from a piano that’s out of tune. Just then the door opens, the wide, old-fashioned double door, and her husband enters, along with several policemen, and accuses her of murdering Maria. Then she speaks passionately in her own defense, sitting naked on the floor in the oblong, drafty room. The one-eyed woman raises her hand and places a finger to her lips in a commanding gesture that calls for silence.

That’s how Face to Face should have been made.

If I had had the experience I have today and the strength I had then, I would have translated this material into practically feasible solutions and not hesitated for a moment.

It would have been a sacrosanct cinematographic piece of poetry.

To me, this is not a continuation of the line from Cries and Whispers. It goes far beyond Cries and Whispers. Here, finally, all forms of storytelling are dissolved.

Instead the daily grind of the screenplay goes on, and the story takes shape. The first half is falling nicely into place. The only thing left is the woman with the blind eye.

October 5:

Could lament forever and ever about pleasure and displeasure, about difficulties and adversities and about boredom, but I will not. I think that I have never been more disinclined and hesitant than I am now! Perhaps I am in touch with a sorrow that wants to appear. Where does it come from? What is it made up of? Is there anyone in the world who has it as good as I do?

My repulsion and my unwillingness, needless to say, stem from the fact that I have betrayed my idea, and I keep jumping from one treacherous ice floe to another.

Sunday, October 13:

Great discouragement, which changes into determination. I feel as if, at the end of this, which is slavery, the real film is hiding. If I push and pull and bluff my way through, perhaps I will haul it out of the darkness, and then it will have been worth the trouble.

There is no doubt that there exists a huge shout trying to find its voice. Then the question is whether I have the ability to release the shout, to set it free.

And this, too, dated October 20:

Will I be able to get close to the point where my own despair is hiding, where my own suicide lies in wait? I don’t know.

This is the true birth: hold me, help me, be kind to me, hold me tight, hold me tight, why isn’t there anybody who cares about me? Why is nobody holding my head? It is far too big. Please, I am freezing, I can’t go on like this. Kill me again, I don’t want to live, it can’t be true, look how long my arms are, and emptiness is everywhere.

The person crying out isn’t Jenny!

On November 1, I write: “Today I finished writing the whole script for the first time. Came right through it and out on the other side.” Then I begin all over again, rereading, correcting, rewriting.

November 24:

Today we are going to Stockholm. So begins the second act, the one focused on the outside world; I can’t say that I’m looking forward to it with great impatience. I am going to meet with Erland [Josephson] and see what he has to say. I hope he’ll be candid. If he thinks I should abandon this project, I will. It’s pointless to throw myself into some big, expensive project when my desire is zero. I am also worried about Twelfth Night. This time I’m getting into something I have never tried before, and it feels difficult, if not impossible. I wonder if it’s not simply that my body and soul are saying “no” after a long period of intense activity; that may well be. Everything is fluid; everything is diffuse. As for me, I am filled with malaise. At the same time I am well aware that a large percentage of this malaise stems from my difficulty in getting started, my fear of people, fear that it won’t be any good, fear of life, of moving at all.

The primal scream. Liv Ullmann.

The primal scream. Liv Ullmann.

Then came the period when I was working on Twelfth Night at the Royal Dramatic Theater.

March 1, 1975:

Returned to Fårö Friday. The premiere of Twelfth Night went very well, and the reviews were for the most part tremendous. Rehearsals went exceedingly quickly. It was like a real party. Made a point of not dealing with Face to Face during this whole time except when it was absolutely necessary. I’m going to concentrate on rewriting the dreams.

Monday, April 21:

Today is the last day at Fårö. Tomorrow we leave for Stockholm, and the following Monday we start filming. It actually feels good, apart from my usual anguish. I even have the impression it’s going to be fun, a kind of challenge. In other words, desire. That terrible depression that followed the writing of the screenplay has disappeared altogether. It was almost like an illness. The trip to the United States was also stimulating. And good for our finances. We can look to the future with confidence.

July 1:

Have just returned to Fårö after having finished shooting. Actually it went terribly fast. All of a sudden we were halfway through, all of a sudden there were only five days left, and then all of a sudden it was finished, and we all met at the Stallmästaregården Restaurant to celebrate, complete with speeches and cigars and nostalgia and confused feelings. I don’t really know how it went. With The Magic Flute, we all knew it was good. Here I know nothing. Toward the end I felt completely exhausted. Anyhow, now it’s over. Liv asked me what I thought. I said, I think it’s fine.

When we were in the United States, Dino De Laurentiis asked me: “Are you doing anything I could have?” I heard myself answer, “I’m making a psychological thriller about the breakdown of a human being and her dreams.” “It sounds great,” he said. So we signed a contract.

This should have been a happy period of my life. I had The Magic Flute behind me, as well as Scenes from a Marriage and Cries and Whispers. I was successful at the theater. Our little company was producing the films of other directors, and the money was flowing in. It was precisely the right time to tackle a difficult task. My artistic self-confidence was as high as it’s ever been. I could do whatever I wanted, and anyone and everyone was willing to finance my efforts.

During the filming of Face to Face everybody was very enthusiastic, and that of course is all-important. Nobody seemed to care that I kept remaking the dreams incessantly, changing them and moving them around. I even stuck in my old Fridell etching with snow on the furniture and the little girl who stands there holding the candle that illuminates the terrible clown.

Two short dream sequences strike me as acceptable. One is when the lady with one eye comes over to Jenny and strokes her hair. The other one, which at least is honestly thought out, is Jenny’s brief encounter with her parents after the automobile accident. From the viewpoint of direction, it’s a rather good scene. They crawl behind the Dutch-tiled stove and start to cry when Jenny hits them. But in one way the scene is poorly directed: Jenny should have remained completely calm rather than acting in the same way as her parents do. I did not understand that at the time. Still, a concrete dream atmosphere does exist at this point.

All the rest is forced. I am roving erratically in exactly what I warn against in my foreword to the screenplay: a landscape of clichés.

Deep inside a yellow cardboard box, I am hiding a terrible little short story. I wrote it during the 1940s. A boy is in his grandmother’s apartment; it is night, and he can’t seem to fall asleep; two tiny people emerge and run across the floor. He catches one and crushes it with his hand. It’s a little girl. The story is about childish sexuality and childish cruelty. My sister insists with emphatic stubbornness that my dark closet originated in Uppsala. It was Grandma’s special method of punishment, not that of my parents. If ever I was locked into a closet at home, it was the one where I kept my toys and the flashlight with a red-and-green light that I could use to play cinema with. So it was actually quite nice and didn’t frighten me at all.

“Two short dream sequences strike me as acceptable.” The brief encounter with the parents. The woman with one eye and Jenny.

“Two short dream sequences strike me as acceptable.” The brief encounter with the parents. The woman with one eye and Jenny.

To sit locked in a closet in my grandmother’s old-fashioned apartment must have been far worse. The only thing is, I have completely suppressed that memory. To me, Grandma was and remained a figure of light.

Here I let her appear in Jenny’s primal ode, but I cannot give shape and form to my memory. The memory arises so suddenly, and is so sharply painful, that I immediately exile it back to darkness. My artistic impotence is total.

But in the point of departure lies a truth. Grandmother could have had two faces.

From my early childhood I remember a conversation full of hate between my maternal grandmother and my father, which I overheard from an adjacent room. They were sitting at the table, drinking tea, and suddenly Grandma spoke in a tone of voice I had never heard her use before. I remember that it frightened me: Grandma had another voice!

That is what I dimly remembered! Jenny’s grandmother should suddenly appear in a frightening light, and then, when Jenny returns home, her grandmother is a sad little old lady.

Dino De Laurentiis was delighted with the film, which received rave reviews in America. Perhaps it did present something new that had never been tried before. Now when I see Face to Face, I remember an old farce with Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Dorothy Lamour. It’s called The Road to Morocco. They have been shipwrecked and come floating on a raft in front of a projected New York in the background. In the final scene, Bob Hope throws himself to the ground and begins to scream and foam at the mouth. The others stare at him in astonishment and ask what in the world he is doing.

“ ’This is how you have to do it if you want to win an Oscar.’” Bob Hope with Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour in The Road to Morocco (Paramount).

He immediately calms down and says, “This is how you have to do it if you want to win an Oscar.”

When I see Face to Face and Liv Ullmann’s incredibly loyal effort on my behalf, I still can’t help thinking of The Road to Morocco.

THE FIRST IMAGE kept coming back, over and over: the room draped all in red with women clad in white. That’s the way it is: Images obstinately resurface without my knowing what they want with me; then they disappear only to come back, looking exactly the same.

Four women dressed in white in a big red room. They came and went, whispered to one another, and were utterly secretive. At the time my mind was on other matters, but since the images kept coming back so insistently I understood that they wanted something from me.

I also point this out in my introduction to the published screenplay of Cries and Whispers:

The scene I just described has haunted me for a full year. In the beginning, of course, I didn’t know what the women’s names were or why they came and went in the gray light of dawn in a red room. Time and time again, I rejected this image and refused to base a film (or whatever it is) on it. But the image has persisted and reluctantly I have identified it: three women who are waiting for the fourth one to die. They take turns sitting with her.

At first my workbook is mostly about The Touch. Under the entry date July 5, 1970, I write:

I’ve finished the screenplay, although not without a fair amount of inner resistance. I baptized it The Touch. As good a name as any other.