BIRGER MALMSTEN PLANNED to visit a childhood friend of his, a painter living in Cagnes-sur-Mer. We traveled together and found a small hotel in the mountains high above the carnation fields with a commanding view of the Mediterranean.

My second marriage had hit rock bottom. So my wife and I tried to revitalize our love by writing letters to each other. At the same time I began to think back to our time in Helsingborg. I sketched a few scenes from a marriage. Much inside me insisted on being expressed, both my personal concept of my place in the world of art and my marital problems of infidelity (and fidelity). More specifically, I wanted to make a film with music streaming through it and out of it.

The symphony orchestra in Helsingborg, though severely lacking in sophistication, exuberantly played the canon of major symphonies. As often as time and circumstances allowed, I sat in on orchestra rehearsals. For their season finale they planned to perform Beethoven’s Ninth. I was allowed to borrow the score from the conductor, Sten Frykberg, and could actively follow, note by note, the musicians and the members of the unpaid but passionate amateur choir. It was a powerful and touching event. I thought it was a magnificent idea for a film.

It seemed so natural that I tripped over the idea. I changed the theatrical people in my autobiographical film to musicians and gave it the title To Joy after Beethoven’s symphony.

I thought my idea utterly brilliant. In relation to my profession, I obviously was not suffering from any neuroses at all. I worked because it was fun and because I needed money.

How many carats the work contained was something I rarely considered. When in this intoxicated state, I could become totally enveloped in my own sense of brilliance.

There is in To Joy a discussion of the importance of being in place punctually when the rehearsal begins and being diligent. As I wrote in The Magic Lantern about the years in Helsingborg: “Our rehearsal periods were short, our preparations were almost nonexistent. What we presented was hastily assembled consumer goods. I think that was a good learning experience, for us very useful. Young people should constantly be faced with new tasks. Their instruments must be tried and hardened because technique can be developed only through steady contact with an audience.”

That the film’s young violinist plays Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto with about the same lackluster skill as I exhibited in Crisis is just part of the whole story.*

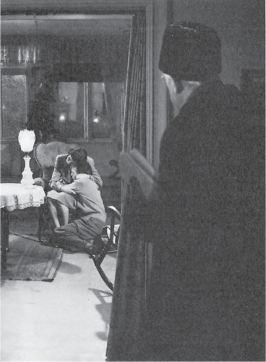

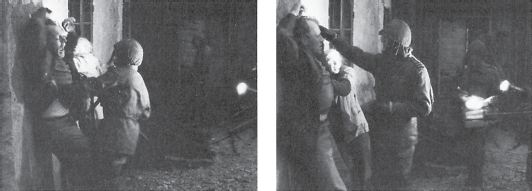

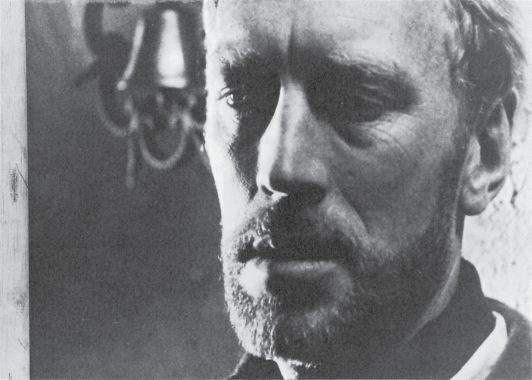

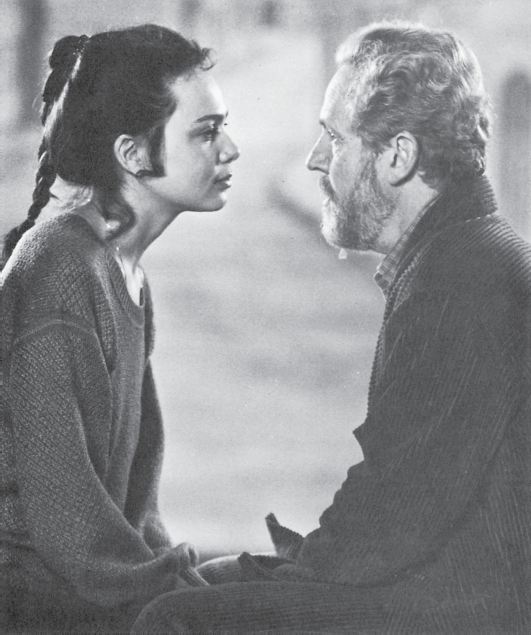

To Joy is a hopelessly uneven film, but it has a few shining moments. A good scene is the confrontation at night between Stig Olin and Maj-Britt Nilsson. It is good because Maj-Britt Nilsson’s adept acting enriches the scene. The clear and honest depiction of a complicated relationship echoes the conflicts in my own marriage.

But To Joy is also an impossible melodrama. A kerosene stove explodes portentously in the beginning of the film, and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is shamelessly exploited. I do understand the techniques used in both melodrama and soap opera quite well. One who uses melodrama as it should be used can implement the unrestrained emotional possibilities available in the genre. Melodrama enables one, as it did me in Fanny and Alexander, to revel in total emotional freedom, but it is crucial to know where to draw the line between what is acceptable and what is downright ridiculous.

To Joy: Maj-Britt Nilsson, Stig Olin, and Victor Sjöström.

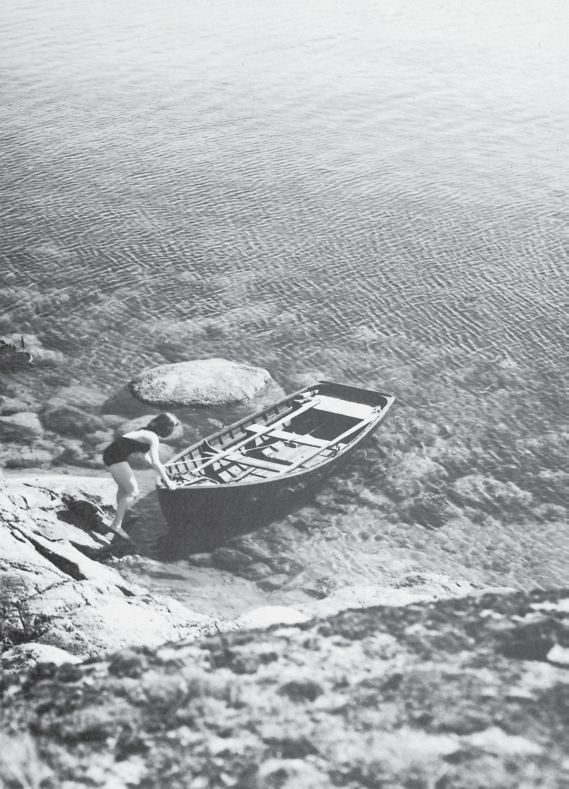

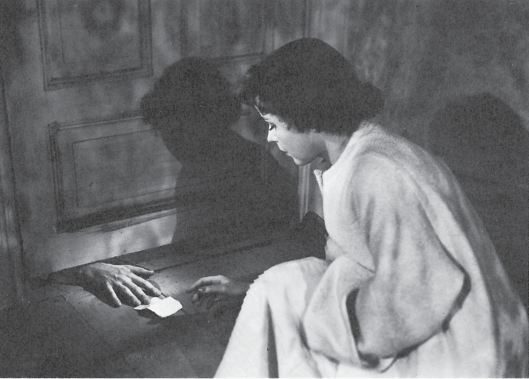

Summer Interlude: “We filmed it in Stockholm’s outer archipelago. … A touch of genuine tenderness is achieved through Maj-Britt Nilsson’s performance.”

I did not know that when I made To Joy. The connection I made by juxtaposing the wife’s death with Beethoven’s “An die Freude” was careless and unbelievably frivolous. My original story worked better. It simply ended with the couple splitting up. They remain with the orchestra, but she receives an offer in Stockholm, which hastens their breakup.

Sadly, I couldn’t handle such a simple, harsh finale to the story.

A general weakness reigns in my films from this period. I had trouble trying to depict the happiness of youth. I believe the problem is that I myself never felt young, only immature. As a child, I never associated with other young people. I isolated myself from my peers and became a loner. At the same time I became dangerously enchanted with the Swedish novelist and playwright Hjalmar Bergman and his elaborately constructed tales of youth. His influence can be seen in Illicit Interlude (Summer Interlude) and created, I believe, the most serious flaw in Wild Strawberries.

The world of youth was alien to me. I stood on the outside, looking in. When I had to formulate dialogue for my young characters, I reached for literary clichés and adopted a coquettish silliness.

In To Joy I presented a series of events that should have been detached and realistic — the scenes demanded distance and perspective — but verged instead on the highly personal. I couldn’t provide a solid foundation for this material, and therefore the house of cards collapsed.

I learned quickly, and already in Summer Interlude [1950] the shape of the personal message was much clearer as I managed to hold it at arm’s length.

Summer Interlude has a long history. Its origin, I see now, lies in a rather touching love affair that I had one summer when my family resided on Ornö Island. I was sixteen years old and, as usual, was stuck with extra studies during my summer vacation and could only occasionally participate in activities with people my own age. Besides, I did not dress as they did; I was skinny, had acne, and stammered whenever I broke my silence and looked up from reading Nietzsche.

It was a fantastic life of laziness and self-indulgence in a pristine, sensuous landscape. But as I said, I was rather lonely. On the far end of this so-called Paradise Island, toward the bay, there lived a girl who was also alone. A timid love grew between us, as often happens when two young lonely people seek each other out. She lived with her parents in a large, strangely unfinished house. Her mother was a somewhat faded yet rare beauty. Her father had suffered a stroke and sat immobile in the large music room or on the terrace facing the sea. Important ladies and gentlemen came for visits to see and admire the exotic rose garden. Actually, it was a little like stepping straight into one of Chekhov’s short stories.

Our love died when autumn came, but it served as the basis for a short story that I wrote the summer after my exams. When I went to Svensk Filmindustri to work as a script slave, I retrieved it and fleshed it out into a movie script. It was entangled in itself and filled with flashbacks, which I couldn’t find my way out of. I wrote several versions, but nothing fell into place. Then Herbert Grevenius came to my aid. He chiseled away all the superfluous episodes and pulled out the original story. Thanks to his efforts, I finally got the screenplay approved for production.

We filmed it in Stockholm’s outer archipelago. The landscape had a special mixture of tempered countryside and wilderness, which played an important part in the differenttime schemes, in the luminescence of summer and in the autumnal twilight. A touch of genuine tenderness is achieved through Maj-Britt Nilsson’s performance. The camera catches her with an affection that is easy to comprehend. She embraced the girl’s story and lifted it higher with her brilliant mixture of playfulness and seriousness. The filming became one of my happy experiences.

But harsher times were ahead. The film crisis, promising a total standstill in motion picture production, was fast approaching, and Svensk Filmindustri was in a hurry to produce the spy thriller This Can’t Happen Here (also known as High Tension in the United States) with Signe Hasso, imported from Hollywood. I agreed to direct it for financial reasons and practically went straight from one shoot into another. Summer Interlude was put aside. It was This Can’t Happen Here that counted.

For me the whole thing was torturous, a good example of how bad you can feel when you must do something you do not want to do. It was not the assignment per se that was making me sick. Later, during the time when movie production was shut down, I put together a series of commercials for the soap Bris (Breeze), and I had a lot of fun challenging stereotypes of the commercial genre by playing around with the genre itself and making miniature films in the spirit of Georges Méliès. Originally, I accepted the Bris commercials in order to save the lives of myself and my families. But that was really secondary. The primary reason I wanted to make the commercials was that I was given free rein with money and could do exactly what I wanted with the product’s message. Anyhow, I have always found it difficult to feel resentment when industry comes rushing toward culture, check in hand. My whole cinematic career has been sponsored by private capital. I have never been able to live on my beautiful eyes alone! As an employer, capitalism is brutally honest and rather generous — when it deems it beneficial. Never do you doubt your day-to-day value — a useful experience which will toughen you.

Summer Interlude: Maj-Britt Nilsson with Stig Olin and Annalisa Ericson in the dressing room mirrors.

Summer Interlude: Maj-Britt Nilsson with Stig Olin and Annalisa Ericson in the dressing room mirrors.

This Can’t Happen Here, as I said before, was complete torture from beginning to end.

I was not at all averse to making a detective story or a thriller; that was not the reason for my discomfort. Neither was Signe Hasso the reason. She had been hailed as an international star who Svensk Filmindustri, with incredible naïiveté, hoped would make the film a raging success all over the world. Therefore we filmed This Can’t Happen Here in two languages: Swedish and English. Signe Hasso, a talented and warm person, unfortunately felt poorly during the entire filming. We were never sure from one day to the next whether she would be euphoric or depressed on the set. It was one difficulty, of course, but not the deciding factor.

A creative paralysis hit me after only four days of shooting.

That was exactly when I met the exiled Baltic actors who were going to participate. The encounter was a shock. Suddenly I realized which film we ought to be making. Among these exiled actors I discovered such a richness of lives and experiences that the unevenly developed intrigue in This Can’t Happen Here seemed almost obscene. Before the end of the first week, I demanded to see Svensk Filmindustri’s chief executive, Carl Anders Dymling, and pleaded with him to cancel the project. But our train was running its course and could not be stopped.

At about this point I had a violent attack of influenza, and from that arose sinus trouble that raged almost comically and tormented me throughout the rest of the filming. My very soul resisted this film, hiding in the deepest darkness of my sinus and nasal passages.

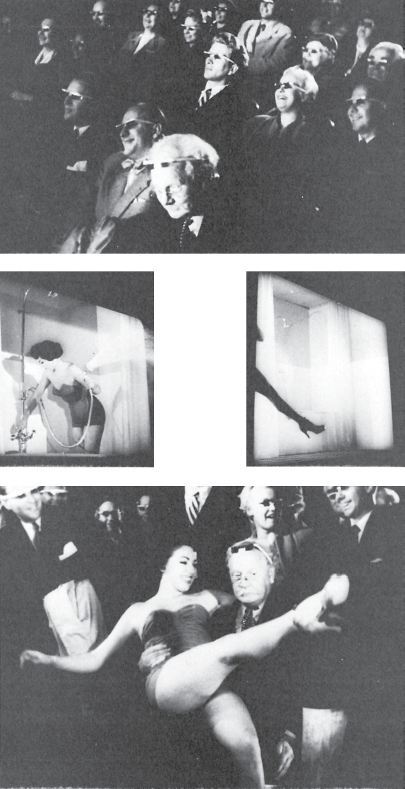

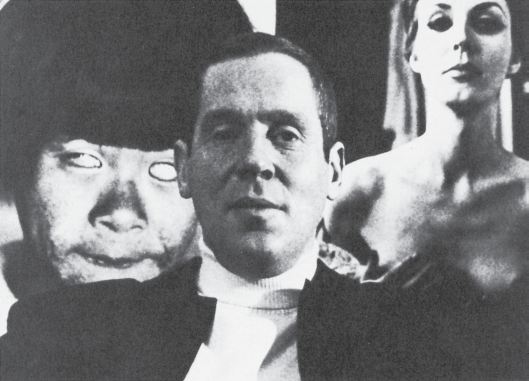

The Bris (Breeze) soap commercials: “Miniature films in the spirit of Georges Méliès,” here with a three-dimensional film-within-a-film.

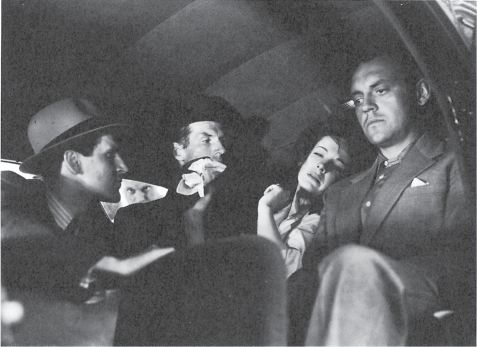

This Can’t Happen Here: the obscene intrigue (Signe Hasso and Ulf Palme). Exiled Baltic actors. A seemingly idyllic interlude with Signe Hasso and Alf Kjellin.

Few of my films do I feel ashamed of or detest for various reasons. This Can’t Happen Here was the first one; I completed it accompanied by violent inner opposition. The other is The Touch. Both mark the very bottom for me.

My punishment did not fail to come from the outside as well. This Can’t Happen Here opened in the fall of 1950 and was regarded as a fiasco, a well-deserved failure, in the eyes of both the critics and the public. During that time Summer Interlude lay there, waiting. It would not be released until a year later.

My reputation as a movie director had the chance to be saved if I made another film. With this in mind, I decided to make She Danced One Summer for Sweden’s Folkbiografer. For some reason this picture’s production was exempted from the general motion picture moratorium. But at the last minute, the head of production, Karl Kilbom, got cold feet. He wanted to see a “beautiful” film, not some “neurotic vulgarity such as, for example, Thirst.” I was fired from the project. However, the determining screen test with Ulla Jacobsson (who rose to international stardom after the film) had already been made.

Instead my next film was Secrets of Women (Waiting Women), and we were given a head start the day after the production ban was lifted. The idea for the film came from my wife at the time, Gun Hagberg. Before we met, she had married into a large family with a big summer place on the Danish island of Jylland. Gun told me how one evening the women of the clan remained sitting at the table after the evening meal and how they began to really talk to each other. With great openness they spoke of their marriages and their loves. I thought this an excellent framework for a film consisting of three stories.

My financial situation after the production standstill forced me to sign a second-rate (to put it mildly) contract with Svensk Filmindustri. I was painfully aware that I had to come up with a successful film. In other words, a comedy seemed an absolute necessity.

Such a comedy was manifested in the third episode of the film: Eva Dahlbeck and Gunnar Björnstrand in the elevator. For the first time, I heard an audience laugh at something I had created. Eva and Gunnar had experience in comedy and knew exactly the many ways to skin a cat. That this little comedy routine in the narrow space of the elevator was funny is completely thanks to them.

The second episode is more interesting to me. For a long time I had considered making a movie without dialogue. In the 1930s, a Czech movie director, Gustav Machaty, made two films — Ecstasy and Nocturno — which were both visual narratives, practically without dialogue. I saw Ecstasy when I was eighteen years old, and it deeply affected me. This was partly a natural reaction because, for once, one was allowed to see a nude woman on screen, but more important, because the movie told nearly everything through images alone.

I recognized in Machaty’s technique something from my childhood. I had once built a miniature movie theater out of cardboard. It had a few rows of seats in front, an orchestra pit, curtains, and a proscenium. I made tiny balconies for the sides. On a sign outside I wrote Röda Kvarn (Red Mill), the name of a popular movie theater in Stockholm.

For film, I drew comic strips on long pieces of paper, which I then pulled through a container fastened behind the cutout square that was my “silver screen.” I made up stories and placed text cards between the pictures but limited myself rather consciously to as few text interruptions as possible. I soon discovered that it was possible to tell stories without text, exactly as in Ecstasy.

Waiting Women: the five women. The three episodes: Jarl Kulle and Anita Björk. Maj-Britt Nilsson. Eva Dahlbeck and Gunnar Björnstrand.

While preparing Waiting Women, I regularly met with the writer Per Anders Fogelström. He was working on a story about a girl and a boy who run away from home together and live in the wilderness of the archipelago before returning to civilization. Together we wrote a screenplay. We delivered it to Svensk Filmindustri along with detailed “directions for use.” My intention was to make a low-budget film under a relaxed schedule, far from the soundstages and with the smallest crew possible. Monika (Summer with Monika) was given the green light to be the second film on my slave contract. Harriet Andersson and Lars Ekborg took a screen test on one of the sets for Waiting Women. Again, I went directly from finishing one film to starting another.

I have never made a less complicated film than Summer with Monika. We simply went off and shot it, taking great delight in our freedom. And the public success was considerable.

It was immensely gratifying to bring out a natural talent such as Harriet Andersson and watch how she behaved in front of the camera. She had acted in the theater and in variety shows and had played small parts in light comedy films such as Mrs. Andersson’s Kalle and The Beef and the Banana. She had also been given, after some hesitation, the ingénue role in Gustaf Molander’s Defiance. When I went to make Summer with Monika, the skepticism was thick in the executive production offices. I asked Gustaf Molander about using Harriet. He looked at me and winked. “If you believe you can get something out of her, I suppose it would be nice.” Only later did I grasp the amiable but improper insinuation in my older colleague’s remark.

Harriet Andersson is one of cinema’s geniuses. You meet only a few of these rare, shimmering individuals on your travels along the twisting road of the movie industry jungle.

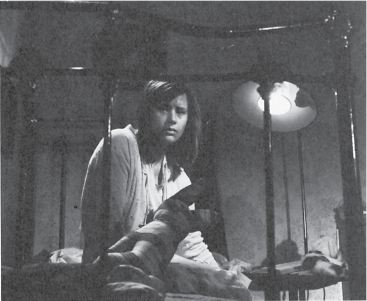

Summer with Monika: before and after. Lars Ekborg, Harriet Andersson.

Summer with Monika: before and after. Lars Ekborg, Harriet Andersson.

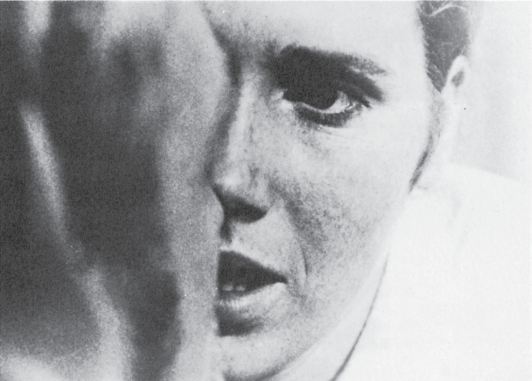

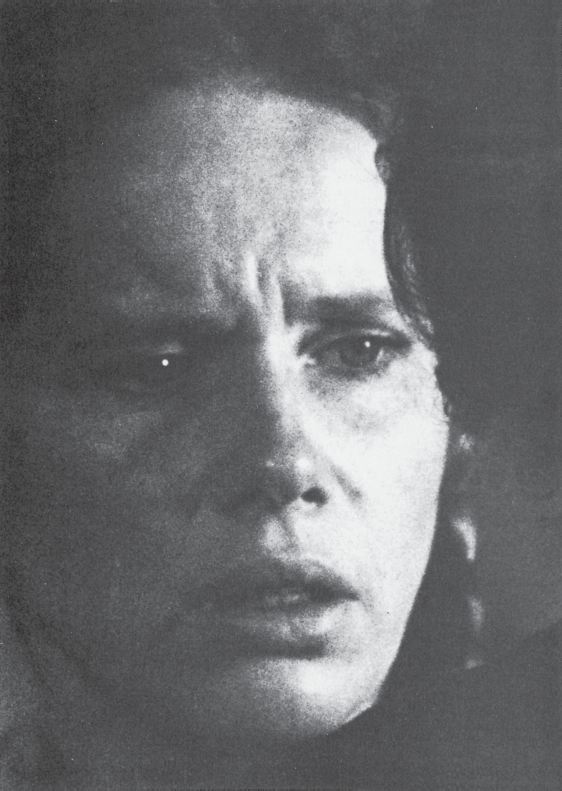

Here is an example of her talent: The summer has ended. Harry is not at home; Monika goes on a date with a guy named Lelle. At the coffee shop he drops a coin into the jukebox. With the swing music resounding, the camera turns to Harriet. She shifts her glance from her partner straight into the lens. Here is suddenly established, for the first time in the history of film, shameless, direct contact with the viewer.

“She shifts her glance from her partner straight into the lens.” Harriet Andersson.

SHAME (THE SHAME) PREMIERED ONSeptember 29, 1968. The following day I made this entry in my workbook:

I’m sitting on Faro Island, waiting. Just as I wished, I am totally isolated, and it feels rather good. Liv is in Sorrento at the festival. Yesterday, the film opened both in Stockholm and in Sorrento. I’m sitting here waiting for the reviews. I’m going to take the ferry at noon to Visby and buy the morning and evening papers at the same time.

It feels good to do this alone. It is good not to have to show my face. Because I am tormented. It’s an incessant ache tinged with fear. I don’t know anything yet. Nobody has said anything. But intuitively I feel very depressed. Because I do believe that the reviews will be lukewarm when they aren’t clearly disparaging. And this time, especially, it will be difficult not to be affected by the criticism. Of course everyone would like to enjoy critical and public success all the time. But it has been a long time now for me. I have a feeling that I am being pushed aside. Things are quiet and very polite around me. It’s hard to breathe. How am I to go on?

Finally, I couldn’t wait any longer. I called the main office of Svensk Filmindustri and asked to speak to the head of Public Relations. He was out on a coffee break. Instead, I spoke to his secretary:

Oh, yes, she had not read the reviews yet, no. They were good, though, five stars in the evening paper Expressen, but nothing to quote, no. Yes, Liv was good, of course, though we know how they write.

By this time I had a fever of 104 degrees and put down the receiver. My heart was beating as if it wanted to jump out of my mouth from shame, exhaustion, and a sense of ennui. All due to my desperation and hysteria. No, I am not particularly happy.

Both passages show two things: 1) the agony of a movie director awaiting his reviews, and 2) his belief that he had made a good film.

When I see Shame today, I find that it can be divided into two parts. The first half, which is about the events of the war, is bad. The second half, which is about the effects of war, is good. The first half is much worse than I had imagined; the second much better than I had remembered.

There are bits and pieces of the first half that are all right. The movie begins well. The couple’s situation and background are effectively established. The good part of the film starts with the moment the war is over and the pain of the aftermath sets in. It begins in a potato field, where Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow move in oppressing silence.

One might say that the authenticity of the second half is disturbed by an overblown scheme involving a wad of paper money that changes hands several times. This scheme reflects an influence from American dramaturgy of the 1950s.

For a long time before making this film I had carried around the notion of trying to focus on the “little war,” the war that exists on the periphery where there is total confusion, and nobody knows what is actually going on. If I had been more patient when writing the script, I would hav depicted this “little war” in a better way. I did not have that patience.

To tell the truth, I was exorbitantly proud of this film. I also felt I had made a contribution to the current social debate (the Vietnam war). I convinced myself that Shame was well made. I had suffered under the same delusion after finishing A Ship Bound for India. And the same thing would happen to me again later when making The Serpent’s Egg.

To make a war film is to depict violence committed toward both groups and individuals. In American film, the depiction of violence has a long tradition. In Japan, it has developed into a masterful ritual, matchlessly choreographed.

When I made Shame, I felt an intense desire to expose the violence of war without restraint. But my intentions and wishes were greater than my abilities. I did not understand that a modern portrayer of war needs a totally different fortitude and professional precision than what I could provide.

Once the outer violence stops and the inner violence begins, Shame becomes a good film. When society can no longer function, the main characters lose their frame of reference. Their social relations cease. The people crumble. The weak man becomes ruthless. The woman, who had been the stronger, falls apart. Everything slips away into a dream play that ends on board the refugee boat. Everything is shown in pictures, as in a nightmare. In a nightmare, I felt at home. In the reality of war, I was lost.

Shame: “The first half is much worse than I had imagined.”

(During the whole screenwriting period, the story was called Dreams of Shame.)

In other words, we are talking about a poorly constructed manuscript. The first half of the film is really nothing more than an endlessly drawn-out prologue that ought to have been over and done with in ten minutes. What happens later could have been built upon, fleshed out, and developed as much as was needed.

I didn’t ever see that. I didn’t see it when I wrote the screenplay; I didn’t see it when I shot the film; I didn’t see it when I edited it. During that time I lived with the idea that Shame was self-evident and emotionally logical all the way through.

That during the course of working one does not see anything wrong with the mechanics of the script is probably due to a self-protective reflex that functions throughout a long and complicated procedure. This defensive mechanism quiets the critical superego. With your self-critical inner voice hollering in your ear, shooting a film would probably become much too heavy and painful to bear.

“The good part of the film starts the moment the war is over and the pain of the aftermath sets in.” With Max von Sydow, Gunnar Björnstrand, and Liv Ullmann.

THE PASSION OF ANNA (A PASSION) WAS MADEon Fårö Island during the fall of 1968 and carries traces of the winds that were blowing in those days both in the real world and in the world of film. In some respects, therefore, it looks very dated. In other ways it is powerful and shows a break with accepted film practices. I look at it with mixed feelings.

On a superficial level it’s obvious to see, the hair and fashion styles of the actresses link the film to that time period. The difference between a dated film and a timeless one apparently is measured by the length of the skirts, and it cuts me to the quick when I see Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann, two grown women, appearing in the childish, extreme miniskirts of the time. I seem to remember putting up a weak resistance, but, when confronted with the power of two women, I unfortunately gave in. That misfortune was not noticeable then but revealed itself later, like writing in invisible ink.

The Passion of Anna is in some ways a variation of Shame. It depicts what I really wanted to show in Shame — the violence manifested in an underhanded way.

Actually, it is the same story but told more credibly.

I had kept a detailed workbook in which I had taken notes, which are interesting to read now. As early as February 1967, there are notes that show me laboring with the idea of Fx00E5;rö as the setting for the Kingdom of Death. Someone walks across the island out of a longing for something that exists far away. Several stops along the journey. Simple, frightening, and strangely exciting.

There you have the basic concept, and it remained as the basis for the finished movie. But suddenly the concept grew in every possible direction. For a while I worked on a complicated project that revolved around two sisters, a dead Anna and a living Anna. Two stories alternating in counterpoint to each other.

On June 30, 1967, my workbook contains the following statement: “One morning I awakened and decided to abandon the story about the two sisters. It feels too large, too unwieldy, and too uninteresting from a cinematic point of view.”

Nothing of the screenplay existed at the time but a detailed outline, in which both story lines were composed of long sequences of dialogue. So when the European Radio Union ordered a television play, it did not take me more than one week to extract The Reservation from my notes and put a piece of theater on its feet. It is therefore understandable that The Reservation and The Passion of Anna are so closely associated.

The rest of my enterprise consisted of extensively reshaping what would turn out to be The Passion of Anna. This process went on all summer long, and in the fall we began filming.

The Kingdom of Death continues to show up again and again in my notes. Today I regret that I didn’t hang onto my original vision more strongly.

Instead, a different movie emerged out of the original vision of the Kingdom of Death. Among other things, the connection to Shame became increasingly important.

In both films the landscape is the same, but the undeniable threats seen in Shame are much more subtle in The Passion of Anna. Or as it says in the text: the warning signs lie beneath the surface.

The dream in The Passion of Anna begins where the reality of Shame ends. Sadly, it is not especially convincing. The fatally stabbed lambs, the burning horse, and the hanged puppy suffice to create the nightmare. The ominous false suns in the introduction have already established the mood and tone of the film.

The Passion of Anna could have been a good film, had the traces of the 1960s not been so evident. They leave an imprint, not only because of the skirts and hairdos, but, even more essentially, because of the important formal elements: the interviews with the actors and the improvised dinner invitation. The interviews should have been cut out. The dinner party should have been vastly different, much tighter.

It is regrettable that I frequently became so worriedly didactic. But I was scared. You are scared when you have, for a long time, been sawing off the branch upon which you sit. Shame was truly not a success. I worked under the pressure of a firm demand that my film be comprehensible. I could possibly defend myself by saying that, in spite of this, it took all my courage to give The Passion of Anna its final shape.

The four leading characters in the film use Johan (Erik Hell) as an accomplice in their game. There exists a parallel between Johan and the fisherman Jonas in Winter Light. Both become victims of the characters’ paralysis and inability to engage in human emotional experience.

My philosophy (even today) is that there exists an evil that cannot be explained — a virulent, terrifying evil — and humans are the only animals to possess it. An evil that is irrational and not bound by law. Cosmic. Causeless. Nothing frightens people more than incomprehensible, unexplainable evil.

The filming of The Passion of Anna took forty-five days and was quite an ordeal. The screenplay had been written in a white heat. It was more a description of a series of moods than a traditional, dramatic film sequence. Ordinarily, I solved any anticipated technical problems immediately in the writing stage. But here I chose to deal with the problems during filming. To some extent this decision was made because of a lack of time, but mostly I felt a need to challenge myself.

The Passion of Anna was also the first true color film Sven Nykvist and I did together. In All These Women we had filmed in color according to the established rules. This time we wanted to make a film in color as it had never been done before.

Contrary to our usual collaborative experiences, we found ourselves in endless conflicts. My intestinal ulcer acted up, and Sven had vertigo. Our ambition was to make a black-and-white film in color, with certain hues emphasized in a strictly defined color scale. It turned out to be difficult. The color negative exposed slowly and demanded a totally different lighting than it would today. The poor results of our efforts confused us, and, regretfully, we argued often.

It was also 1968. The seeds of rebellion from that year began to reach even the crew at Fårö.

Sven had an assistant photographer with whom we had worked on several earlier films. He was a short man with round glasses, like a military serviceman. Nobody had been more diligent and industrious than he. Now he was transformed into an active agitator. He called big meetings. He declared that Sven and I behaved like dictators and that all artistic decisions should be made by the whole crew.

I declared that those who did not like our way of working could return home the next day with their salaries intact. I was not going to change my method and schedule of shooting and did not intend to accept artistic decisions from the crew.

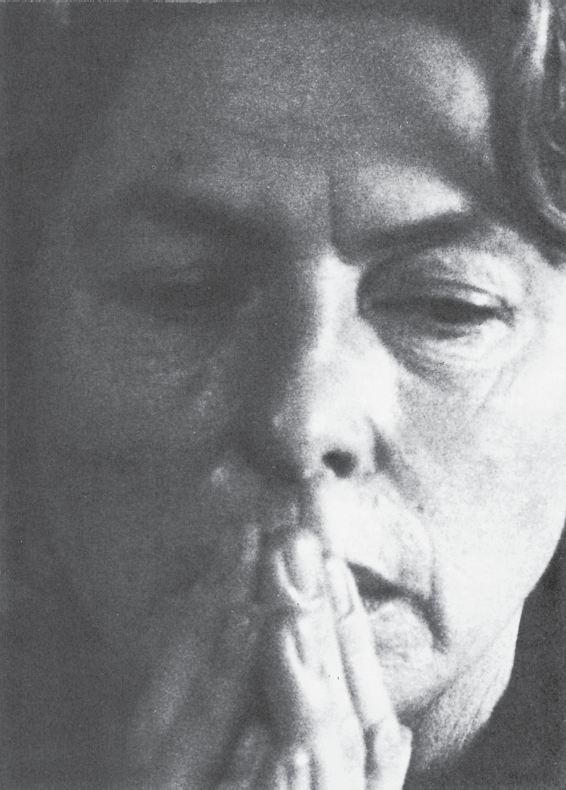

The Passion of Anna: the four leading actors. Erland Josephson. Bibi Andersson. Max von Sydow. Liv Ullmann.

Nobody wanted to go home. I saw to it that our agitator was assigned to other duties, and the filming of The Passion of Anna continued without any further protest meetings.

The filming, however, became one of the worst I have ever experienced, equal to This Can’t Happen Here, Winter Light, and The Touch.

I HAD NOT SEEN Brink of Life (So Close to Life) since I made it in the fall of 1957. But this fact did not stop me from speaking of it in derogatory terms. When Lasse Bergström and I finished our taped conversations about my films and turned off the machine for good, we discovered to our amazement that Brink of Life had not been mentioned, not one word, not even a footnote. We agreed that this omission was strange indeed. So I finally decided to see the film, but at that point I uncovered a stubborn resistance inside me, one hell of a resistance, and I don’t know why.

I watched the film alone in my screening room on Fårö and was surprised by the resentment I felt. The film had been an assignment: I had promised (I no longer remember why) to make a film for Sweden’s Folkbiografer. I read Ulla Isaksson’s fine short story collection, Aunt of Death, and was captivated by two of the stories, which, if put together, could be made into a screenplay. The screenwriting proceeded quickly and was fun (as it always is with my friend Ulla). I was given the crew I wanted; Bibi Lindström built a manageable maternity ward; everybody was in a good mood; and the work proceeded swiftly. Why so apprehensive? Oh yes! I can see weaknesses and shortcomings, more clearly now than thirty years ago, but how many films from the 1950s still hold up today? Our criteria have changed (and in film and theater this happens at a dizzying speed). A definite advantage to directing a stage performance is that it dives into the ocean of oblivion and disappears. Films live on. I wonder how this book would have turned out if my opus had disappeared, and I had based my comments solely on notebooks, photographs, newspaper reviews, and faded memories?

But Brink of Life exists exactly as it was seen and heard at the premiere on March 11, 1958, and I sat watching the same film years later in the darkness, alone and influenced by no one. What I saw was a well-told but a bit too long-winded story about three women in a maternity ward. Everything was honest, warmhearted, and intelligently done, with first-class performances, but too much makeup, a deplorable wig on Eva Dahlbeck, poor cinematography in parts, and a few too many literary references. When the movie ended, I sat there, surprised at myself and a little annoyed — I suddenly liked the old film. It was nicely behaved and accurately done and in all probability very useful when it was running in the movie theaters.

I recall that there had been medical attendants stationed in the theaters. People had a tendency to faint from pure fright. I also recall that the medical adviser for the film, Dr. Lars Engström, allowed me to be present during a birth at the Karolinska Hospital. It was a traumatic and edifying experience. Even though I was the father of five children by that time, I had never been present at any of the births (that’s how things were back then). Instead, I got drunk or played with my miniature electric trains or went to the movies or rehearsed or worked on a movie or, inappropriately, paid attention to other women. I don’t quite remember the details. Anyhow, the delivery at Karolinska Hospital was splendid and not the least complicated. The mother was young and plump and gave birth with both screams and laughter. The atmosphere was exhilarating. I came close to fainting twice, and finally I had to leave the room and hit my head against a wall in order to come around. Then I went back to my work, a bit shaken but immensely grateful.

Brink of Life: “The actresses remain its biggest asset.” Bibi Andersson. Eva Dahlbeck. Ingrid Thulin.

Brink of Life: “The actresses remain its biggest asset.” Bibi Andersson. Eva Dahlbeck. Ingrid Thulin.

I don’t want to pretend that filming proceeded without complications. Folkbiografer owned a long, narrow studio, which was once a school gymnasium, deep down in the basement of an old ramshackle building in the Östermalm area of Stockholm. The adjacent spaces were rudimentary or nonexistent. The ventilation was questionable — the air came in at sidewalk level, pulling in the exhaust from passing cars. It was cramped, dirty, and dilapidated. The Asian flu was raging at the time, and we all fell like dominoes, but we could not cancel or postpone since the actors had contracts for other work immediately following this shooting. To carry on filming with a fever of 104 degrees would seem impossible. It turned out to be perfectly possible. Everyone walked around with masks. From time to time (rather frequently) we went behind the sets, where laughing gas was kept. Laughing gas is as addictive as dope, though it has a shorter effect.

Max Wilén, the cameraman, turned out to be an adequate craftsman without any sensitivity or joy. We carried out a gloomy collaboration with sullen but polite decorum. The laboratory was also a disaster (scratches and dirt on the developed film).

All together, the film isn’t much. The actresses remain its biggest asset. Just as in other pressured situations, these women proved their professionalism, inventiveness, and unshakable loyalty. They had the ability to laugh in the face of trouble. They had sisterhood. Consideration and caring for each other.

Actors, yes, they deserve a special chapter, but I don’t know if I’d be able to explain and illuminate how each one influenced the origin and composition of my films.

How would Persona have looked if Bibi Andersson had not played Alma, and what would have become of my life if Liv Ullmann had not committed herself both to me and to Elisabet Vogler? And no Harriet in Summer with Monika? Or The Seventh Seal without Max von Sydow? Victor Sjöström in Wild Strawberries’? Ingrid Thulin in Winter Light? I would never have dared to make Smiles of a Summer Night without Eva Dahlbeck and Gunnar Björnstrand.

I often saw the actors outside the studios in other contexts besides work, but my motives still revolved around my films. Ah, the grandmother, Gunn Wållgren, is a natural. Of course, she must play the grandmother in Fanny and Alexander. Without Lena Olin and Erland Josephson, I would never have written After the Rehearsal because these two actors inspired me and gave me the desire to make it. Ingrid Bergman and Liv Ullmann were necessary for Autumn Sonata. So many mornings, lunch hours, and deliberations. So much joy, confusion, and tenderness. All this devotion — once the shooting ended — changed in intensity and manner and stabilized or paled or disappeared. Love, touching, and kissing and perplexity and tears. The four women in Cries and Whispers: Kari Sylwan, Harriet Andersson, Liv Ullmann, Ingrid Thulin. I have a behind-the-scenes photograph taken during the filming; they are sitting in a row on a low couch, all clad in black, and solemn; Harriet is made up and dressed as a corpse. Suddenly they begin to bob up and down on the couch. It has strong springs, and all four of them bob up and down, bump into each other, and laugh. What an assembly of female experience and what great professional accomplishment.

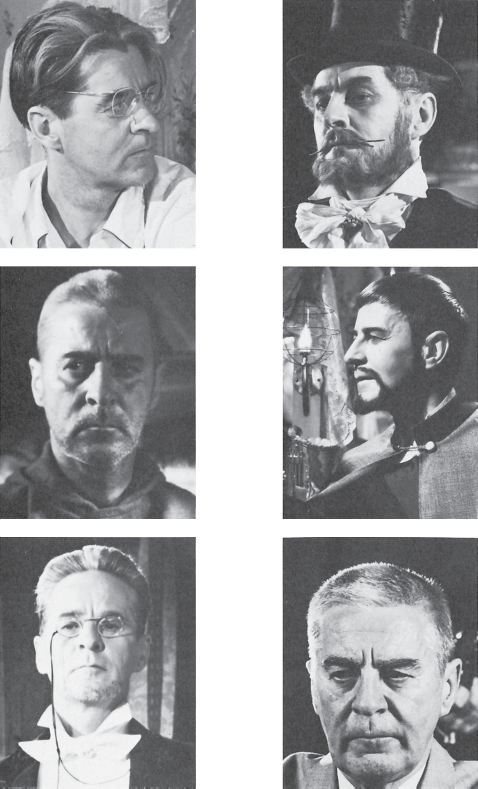

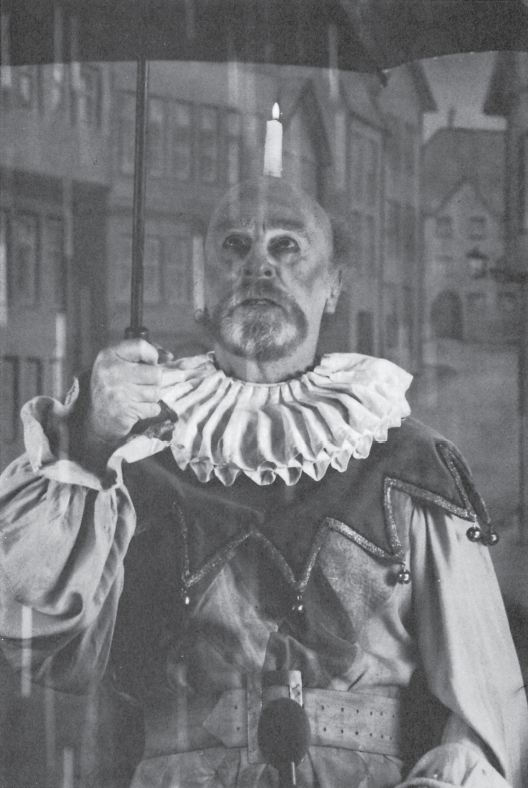

Gunnar Björnstrand regarded me with a darkly narrowed look, his mouth smiling sarcastically; we were two samurai in wild combat, a fight-to-the-end warrior’s story. Then he fell ill and had difficulty memorizing his lines; he suffered a catastrophic opening night at a private theater, and, to top it off, he was panned by a couple of fastidious drama critics in Stockholm. I wanted very much for him to be part of my last film since we had worked together throughout my career. (Our collaboration began in 1946 when he played Mr. Purman in It Rains on Our Love.) So I wrote a part especially for Gunnar, moderately adjusted to his handicap. He played the head of the theater in Fanny and Alexander, business manager, director, and Père Noble in one person. The theatrical group in the film performs Twelfth Night. Gunnar plays the clown. At the end he sits on a small ladder with a lighted candle on his balding head and a red umbrella opened in his hand. He sings: “For the rain it raineth every day.” It rains, and everything is beautiful and touching, and done in the good taste of Gunnar Björnstrand. All day long, the cameraman making our documentary kept his camera unremittingly aimed at Gunnar. Nobody, not even I, knew that he was immortalizing this remarkable day at the South Theater.

Gunnar had a difficult time. He had trouble with his memory and his coordination. There were endless retakes, but neither he nor I had the faintest intention of giving up. He fought heroically with his handicap and his failing memory; he fought and did not give in for a moment. Finally all of the clown was on reel. The triumph was complete.

In the documentary about the filming of Fanny and Alexander — a documentary that runs a little over two hours — the central position is Gunnar Björnstrand’s struggle and triumph. I had edited the footage down from a considerable amount of material, thousands and thousands of feet, into a film within the film, about twenty minutes long.

To be on the safe side, I asked Gunnar and his wife to approve the sequence on him. They said they were satisfied. I was happy; I felt that I had built a monument to a great actor’s last victory, not just any kind of victory but a victory at the highest artistic level. Later on, Gunnar’s widow retracted her approval and demanded that the part with the song of the clown be taken out. Regretfully, I saw myself forced to comply with her request. But we kept the negative. Gunnar Björnstrand’s greatest triumph as an actor shall not perish.

When it comes to the director’s choices and the genesis of a new theatrical production, the actors’ influence can be even more important. Jarl Kulle’s King Lear, Peter Stormare as Hamlet, Bibi Andersson portraying the Legend. I am sitting opposite Gertrud Fridh in the green-painted canteen at the Malmö theater. We linger over old memories. We have worked together for so many years, first in Gothenburg, then in Stockholm and Malmö. We gossip and talk nonsense. The winter of southern Sweden can be seen through the large, dirty windows facing the Theater Park, a stingy, bluish shimmer; the ceiling lights have already been turned on. Gertrud’s face is illuminated twice — by the cold light from outside and by the warm lights above; her voice is tired but purrs on intensely; her gray-green eyes shine with a special luster. Suddenly I think: There she sits, my Célimène! Gertrud is perfect for Célimène in The Misanthrope. Next year I plan to direct The Misanthrope, and you have to play Célimène, you do want to, don’t you, Gertrud? Oh yes, she would like to, but right at this moment she is not completely sure of who Célimène is, and what kind of a figure is the Misanthrope? Yet Ingmar looks happy and eager, so I don’t have the heart to express any doubt. Yes, Gertrud Fridh, the fire, the welding flame that burns her so terribly and so frighteningly. Hedda Gabler, the big tragic tone, the humor, the cruel playfulness. Yes!

When I directed A Dream Play a few years ago, the smallbut crucial role of the dancer was played by a young actress, Pernilla Östergren. She had just played a cheery nursemaid who walks with a limp in Fanny and Alexander. Now we were rehearsing A Dream Play. I watched Pernilla, her strength, her eagerness, and her straightforwardness (even when she did something wrong, it was good). It struck me suddenly that finally, after many years of waiting, the Royal Dramatic Theater had a new Nora! I grabbed hold of her after rehearsal and told her that in three years or at the most four, she would play Nora.

Gunnar Björnstrand in A Lesson in Love, Sawdust and Tinsel, The Seventh Seal, Smiles of a Summer Night, The Magician, and The Ritual. His last triumph: Fanny and Alexander.

The theater is carried by the strength of its actors. Directors and art directors can do whatever they want; they can sabotage themselves, the actors, and even the playwrights. When the actors are strong, that’s when the theater thrives. I remember a production of Three Sisters that had been analyzed and rehearsed to death, ground down to snuff by an old, disillusioned European director. The diligent actors submissively walked around like sleepwalkers, bored stiff. A queen dressed in black rose above this grayness, uncompromising and furiously alive: Agneta Ekmanner.

I am fully aware that what I have just written does not bear any connection to my contemplation of Brink of Life. Yet perhaps it does. Most of the time, I write my own screenplays. I write, and then I rewrite. My workbooks bear witness to the lengthy process (often to my surprise later). The dialogue is put through a strict regimen, is put on a diet, made denser, fleshed out, and erased; words are tried and replaced. In the final round, big chunks disappear (“kill your darlings”). By the time the actors finally take over, transforming my words through their own expression, I have, in general, lost contact with the original meaning of the lines. These artists give new life to the scenes that I have nagged to death. I feel happy but reserved and yet satisfied; oh, did I write that? Oh yes, of course, that’s exactly what I meant to say, though I had forgotten it during the long and extremely solitary process of revision.

With Gertrud Fridh: “The fire, the welding flame that burns her.” Pernilla Östergren: “A cheery nursemaid who walks with a limp in Fanny and Alexander.”

With Gertrud Fridh: “The fire, the welding flame that burns her.” Pernilla Östergren: “A cheery nursemaid who walks with a limp in Fanny and Alexander.”

In the case of Brink of Life, the situation was totally different. I felt a responsibility toward the words that Ulla Isaksson had written. I had to master a reality that was both familiar and alien: women and childbirth. I found myself literally “on the brink of life.” Many of the side effects of childbirth were unexpected: one hospital room contained six new mothers and newborn children only hours old. Swelling breasts, sour milk stains everywhere, innumerous physical conditions, the content and attentive animal side of the vocation. I felt nauseous and could only relate all this to my own inadequate experiences as a daddy, eternally awkward, eternally fleeing.

Ingrid Thulin plays Cecilia, who is only in her third month and close to losing her baby. She throws off the covers and sees, in terror and with cold sweat pouring, that the bed and sheets are covered with blood, all the way up to her breasts. Our technical consultant, a midwife who was present on the set every day, created the blood (from an ox, slightly diluted with some chemical dye to give the right tint). I remember my sudden nausea at the sight and the personal memory that resurfaced from my past of a terrified girl crouching over the toilet with blood gushing out between her legs.

Although I handled the words and actions of Ulla Isaksson’s characters with relentless professionalism and with teeth clenched, I sometimes thought in desperate moments that had I known, really known, what I was getting into, I would not have done it. I swam like a person drowning, searching for a bottom to stand on but finding none there. To top it all off, I had an attack of that devilish Asiatic flu. And, of course, I was totally knocked out.

The four actresses were kind and remained untroubled by my impediments. They could see that I was not feeling well. In spite of the demands of acting, they treated me with indulgent kindness. I was grateful; I am nearly always grateful for the tolerance of my actors. When we part after a period of collaboration, I find myself in the grips of severe separation anxiety and an ensuing depression. People sometimes seem surprised that I abstain from attending opening nights and wrap parties. There is nothing strange about it. I have already cut the emotional ties of our relationship. It hurts me, and I cry inside. In such a state, who wants to go to a party?

After the Rehearsal is actually a dialogue between a young actress and an old director:

Anna: How can you know for sure that you say the right thing to an actor?

Vogler: I don’t know it. I feel it.

Anna: Aren’t you ever afraid of feeling the wrong thing?

Vogler: When I was younger and had reason to be afraid, I didn’t understand that I had reason to be afraid.

Anna: The road for many good directors is lined with humiliated and crippled actors. Have you ever taken the trouble to count your victims?

Vogler: No.

Anna: Perhaps you haven’t left any victims behind you?

Vogler: I don’t think I have.

Anna: How can you be so sure?

Vogler: In life, or let us say in the real world, I believe there are human beings who do carry in themselves injuries from my rampaging, just as I carry injuries from their treatment of me.

Anna: Not in the theater?

Vogler: No. Not in the theater. Perhaps you wonder how I can be so sure, and now I am going to tell you something that sounds both sentimental and exaggerated but which, nevertheless, is absolutely true. I love actors!

Anna: Love?

Vogler: Exactly. I love them. I love them as much as anything in the world; I love their profession; I love their courage or their contempt of the world or whatever they want to call it. I love their deception but also their coldhearted sincerity, which stops at nothing. I love it when they try to manipulate me, and I envy them their gullibility and their keen insight. Yes, I love these actors without reservation; I love them magnificently. Therefore I cannot do them harm.

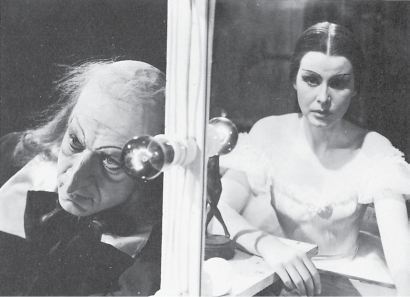

After the Rehearsal: “Actually a dialogue between a young actress and an old director” Lena Olin and Erland Josephson.

After the Rehearsal: “Actually a dialogue between a young actress and an old director” Lena Olin and Erland Josephson.

THE OUTLINE FOR AUTUMN SONATA was written March 26, 1976. Part of the story is the whole tax evasion scandal that fell upon me in the beginning of January: I ended up at the Karolinska Hospital’s pyschiatric clinic, then at the Sophiahemmet, and finally on Fårö. After three months the indictment was repealed. The charge was reduced from that of a serious crime to one of simple tax understatement. My initial reaction was euphoria.

This is what it says in my workbook:

The night after the acquittal, when I cannot go to sleep in spite of sleeping pills, it occurs to me that I want to make a film about the mother-daughter, daughter-mother relationship, and I must have Ingrid Bergman and Liv Ullmann in the two roles, and no one else. Eventually, there may be room for a third character.

It should look something like this: Helena,* who is not a devastating beauty like her ancient namesake, is thirty-five years old and married to a gentle pastor named Viktor. They live in the parsonage near the church and lead a quiet life among their congregation and with the changing seasons ever since their small son died of a unexplained illness. He was six years old when he died and named Erik. Helena’s mother is a concert pianist, now touring around the world. She is expected to arrive soon for her annual visit with her daughter. Actually, she has not come to see them for a few years, so there is a great to-do in the parsonage, elaborate preparations, and happy but anxious expectations. Helena has waited a long time for this meeting with her mother. She also plays the piano, and her mother usually gives her lessons. Therefore, sincere joy pervades this visit that both mother and daughter have looked forward to with both anxiety and fervor. The mother is in a splendid mood. At least she manages to act as if she were in a splendid mood. She finds everything arranged perfectly; even the hard wooden board (for her back) has been placed in her bed in the guest room. She has brought goodies from Switzerland.

The church bells ring. Helena wants to take her mother to the grave, Erik’s grave. Helena goes there every Saturday. She admits that Erik visits her there sometimes, that she can feel his small, cautious caresses. Her mother finds this fixation on the dead child alarming, and she tries, carefully choosing her words, to make Helena see that she and Viktor should adopt or try to have another child. Then later, Helena plays something for her mother, and her mother pays her a number of compliments. But, to insure the purity of the piece, she plays it again herself, thereby crushing her daughter’s meek interpretation, quietly but effectively.

The second act begins with the mother fighting insomnia. She takes sleeping pills, she reads her books, she murmurs her prayers, but she still can’t sleep. Finally she gets up and goes into the living room. Helena hears her, and here follows the grand unmasking. The two women talk about their relationship. For the first time Helena dares to tell the truth of how she really feels. Her mother is completely shaken up by all the hatred and contempt that Helena reveals.

Then it is the mother’s turn to speak about herself, her bitterness, her loathing, her despair, her loneliness. She speaks of the men in her life, about their ultimate indifference, and how they humiliate her by always chasing after other women. But the scene becomes even more profound: The daughter finally gives birth to the mother. Through this reversal they unite for a few brief moments in perfect symbiosis.

Nevertheless, the mother leaves the next morning. She can’t stand the hush or her raw feelings. She arranges it so that someone sends her a telegram saying she must return to work immediately. Helena overhears the telephone conversation. Her mother has left, it is Sunday, and Helena prepares to go to church to listen to her husband’s sermon.

Instead of just two characters in the film, they became four. That idea that Helena gives birth to her mother is a difficult one to convey and one which, I’m sad to say, I abandoned. Characters have a way of following their own paths. In the old days I tried to control and force them, but over the years I became wiser and learned to let them behave as they wished. The result: their hate becomes cemented. The daughter can never forgive the mother. The mother can never forgive the daughter. Forgiveness can be found only through connection with the fourth character, a sick girl.

Autumn Sonata was conceived in one night, in a matter of hours, after a period of total writer’s block. The lingering question is, why this: Why Autumn Sonata? It contained nothing that I had been thinking about before.

The idea of working with Ingrid Bergman was an old desire, but that did not initiate this story. The last time I had seen her was at the Cannes Film Festival at the screening of Cries and Whispers. She had snuck a letter into my pocket, in which she reminded me of my promise that we would make a film together. Once long ago we had planned to adapt Hjalmar Bergman’s novel The Boss, Mrs. Ingeborg to film.

A puzzling element remains: Why did I choose this story, and why was it so complete? It was more finished in the outline than in its final execution.

I wrote the screenplay for Autumn Sonata in a few weeks in order to have something up my sleeve in case The Serpent’s Egg flopped with a somersault. My decision was final: I would never work again in Sweden.

That is the reason I made the strange arrangement to shoot Autumn Sonata in Norway. As it turned out, I felt perfectly content to work in the primitive studios on the outskirts of Oslo. Built in 1913 or 1914, the buildings have been left just as they were. Of course, when the wind blew in certain directions, the air traffic passed right overhead, but otherwise it was old-fashioned and cozy. Everything we needed was available there, even though the place was dilapidated and had not been kept up. The crew members were friendly but a little amateurish.

The actual filming was draining. I did not have what one would call difficulties in my working relationship with Ingrid Bergman. Rather, it was a kind of language barrier, but in a profound sense. Starting on the first day when we all read the script together in the rehearsal studio, I discovered that she had rehearsed her entire part in front of the mirror, complete with intonations and self-conscious gestures. It was clear that she had a different approach to her profession than the rest of us. She was still living in the 1940s.

Autumn Sonata: “I must have Ingrid Bergman and Liv Ullmann in the two roles, and no one else.”

I believe that she possessed some sort of inspired system of working, albeit a strange one. In spite of her mechanisms for receiving director’s cues not being placed where one expected to find them — and where they ought to be — she still must have been somehow receptive to suggestions from two or three of her former directors. After all, she had done excellent work in several American films.

In Hitchcock’s films, for instance, she is always magnificent. She detested the man. I believe that with her he never hesitated to be disrespectful and arrogant, which evidently was precisely the best method to make her listen.

I discovered early into our rehearsals that to be understanding and offer a sympathetic ear did not work. In her case I was forced to use tactics that I normally rejected, the first and foremost being aggression.

Once she told me: “If you don’t tell me how I should do this scene, I’ll slap you!” I rather liked that. But from a strictly professional point of view, it was difficult to work with these two actresses together. When I look at the film today, I see that I left Liv to shift for herself when I ought to have been more supportive. Liv is one of those generous artists who give everything they have. In a few scenes, she sometimes goes astray. That is because I paid too much attention to Ingrid Bergman. Ingrid also had some trouble remembering her lines. In the mornings she was often crabby and angry, which was understandable. She lived with constant anxiety over her own illness* and at the same time found our way of working unfamiliar and frightening. But she never made any attempt to back out. Her conduct was always extraordinarily professional. Even with her obvious frailties, Ingrid Bergman was a remarkable person: generous, grand, and highly talented.

Halvar Björk and Liv Ullmann. With Ingrid Bergman.

A French critic cleverly wrote that “with Autumn Sonata Bergman does Bergman.” It is witty but unfortunate. For me, that is.

I think it is only too true that Bergman (Ingmar, that is) did a Bergman.

If I had had the strength to do what I intended to do at the beginning, it would not have turned out that way.

I love and admire the filmmaker Tarkovsky and believe him to be one of the greatest of all time. My admiration for Fellini is limitless. But I also feel that Tarkovsky began to make Tarkovsky films and that Fellini began to make Fellini films. Yet Kurosawa has never made a Kurosawa film.

I have never been able to appreciate Buñuel. He discovered at an early stage that it is possible to fabricate ingenious tricks, which he elevated to a special kind of genius, particular to Buñuel, and then he repeated and varied his tricks. He always received applause. Buñuel nearly always made Buñuel films.

So the time has come for me to look in the mirror and ask: Where are we going? Has Bergman begun to make Bergman films?

I find that Autumn Sonata is an annoying example.

What I will never know is this: How did it happen that this film was Autumn Sonata? If you carry around a story inside long enough or keep dwelling on a certain subject as happened with Persona or Cries and Whispers, it is possible to discern how a film evolved and why it ended up as it did. But how did Autumn Sonata suddenly burst forth, looking the way it does, like a dream? … And perhaps that is its weakness: it should have remained a dream. Not a film of a dream but a dream of a film: two characters. Background and everything else ought to have been pushed to the side. Three acts in three kinds of lighting: one evening light, one night light, and one morning light. No cumbersome sets, two faces, and three kinds of lighting. Without a doubt that is how I first imagined Autumn Sonata.

There is something close to an enigma in the concept of the daughter giving birth to the mother. Therein lies an emotion that I was not able to realize and carry through to its conclusion. On the surface, the finished film resembles the outline, but actually that is not the case.

I am drilling, and either the drill breaks or else I don’t dare drill deeply enough. Or else it is because I don’t have the strength, or I don’t realize that I should drill deeper. Then I pull up the drill and don’t take that extra dizzying step. I pull up the drill and declare myself satisfied. That is an unerring symptom of creative exhaustion, exceedingly dangerous because it doesn’t hurt.

Notes

*Crisis was the first film Bergman directed, in 1945.

*In the actual film, this character is called Eva, and Helena is the name of Eva’s handicapped sister.

*At the time she made Autumn Sonata, Ingrid Bergman was fighting cancer. She died in 1982.