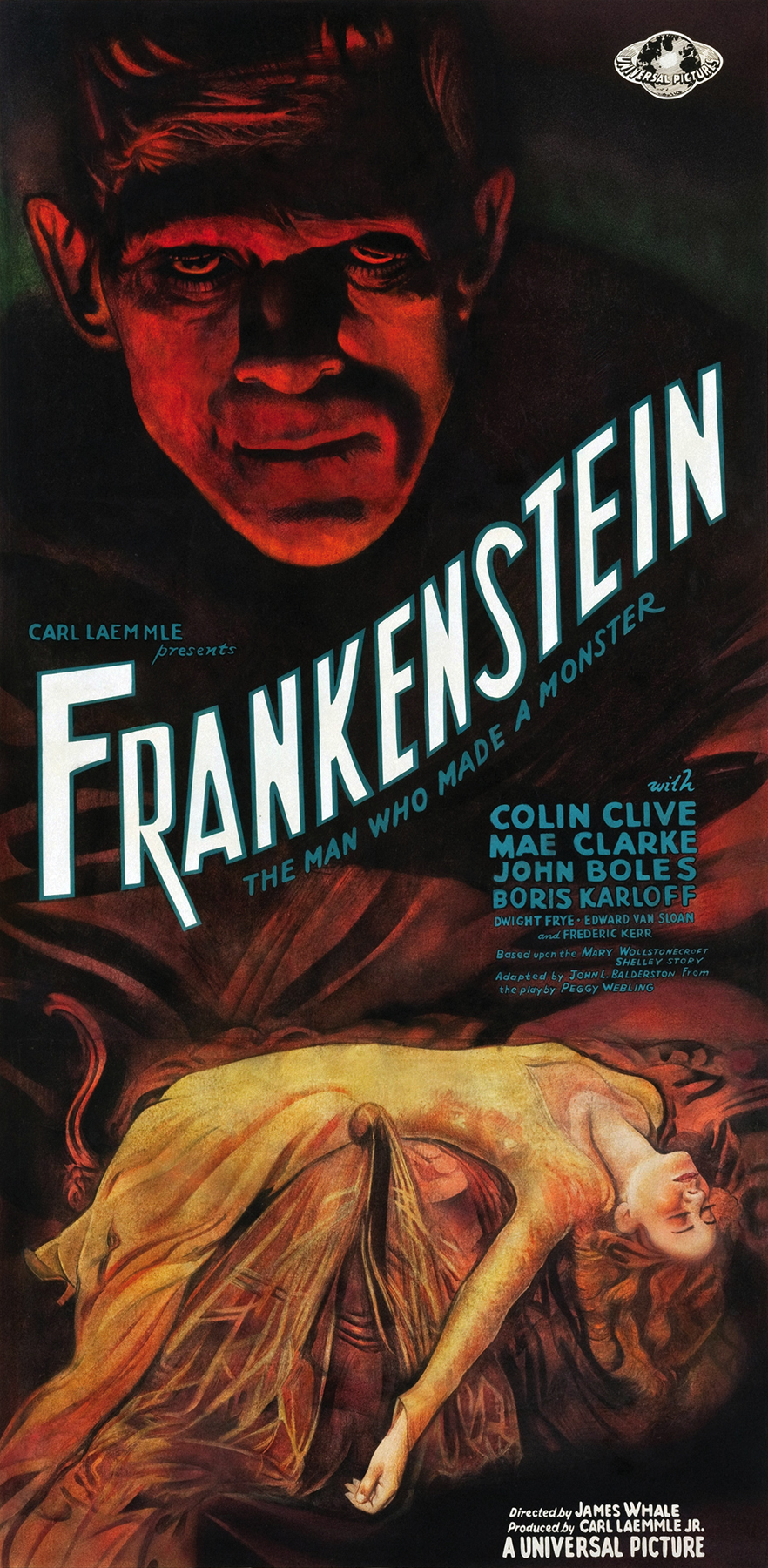

1931

DIRECTOR: JAMES WHALE PRODUCER: CARL LAEMMLE JR. SCREENPLAY: GARRETT FORT AND FRANCIS EDWARD FARAGOH, ADAPTED FROM THE PLAY BY PEGGY WEBLING AND BASED ON THE NOVEL BY MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT SHELLEY STARRING: COLIN CLIVE (HENRY FRANKENSTEIN), MAE CLARKE (ELIZABETH), JOHN BOLES (VICTOR MORITZ), BORIS KARLOFF (THE MONSTER), EDWARD VAN SLOAN (DOCTOR WALDMAN), FREDERICK KERR (BARON FRANKENSTEIN), DWIGHT FRYE (FRITZ)

Frankenstein

UNIVERSAL • BLACK & WHITE, 71 MINUTES

By piecing together parts from dead bodies, scientist Henry Frankenstein creates a living monster with an abnormal brain.

Originally published in 1818, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus has captured the public’s imagination for two hundred years. Though Shelley’s novel has been adapted countless times over two centuries, James Whale’s Frankenstein remains the definitive cinematic version, enduring as a groundbreaking crossover of both sci-fi and horror. As stylish and disturbing today as it was in 1931, Frankenstein is an example of 1930s studio-system artistry at its finest.

Mary Shelley gave birth to a science-fiction archetype with her tale of a young scientist creating life from the dead. After playwright Peggy Webling modernized the novel for her 1930 London stage play, Universal bought the film rights for its Dracula (1931) star, Bela Lugosi. Director Robert Florey shot a long-lost screen test of Lugosi as the monster, but neither Lugosi nor the studio was happy with the results. Lugosi dropped out and producer Carl Laemmle Jr. switched directors, assigning Frankenstein to James Whale, who had crafted the precode melodrama Waterloo Bridge (1931) with subtlety and sophistication. Whale jumped at the chance to, as he put it, “dabble in the macabre.”

His imagination sparked by German expressionist films like The Golem (1920), the director employed extreme camera angles and Gothic settings to cast a dark spell over the audience. Frankenstein, a complex story suffused with philosophical and moral themes, is streamlined by Whale, its essence distilled to the shocking story of a man who builds a monster. The film’s lack of background scoring, a detriment to some early talkies, works in Whale’s favor. Many of the most powerful scenes involve little dialogue and no music: the elevation of the platform as the creature is brought to life in a thunderstorm; our first terrifying look at the monster’s sunken face; the woodcutter silently carrying his daughter’s lifeless body through the town streets.

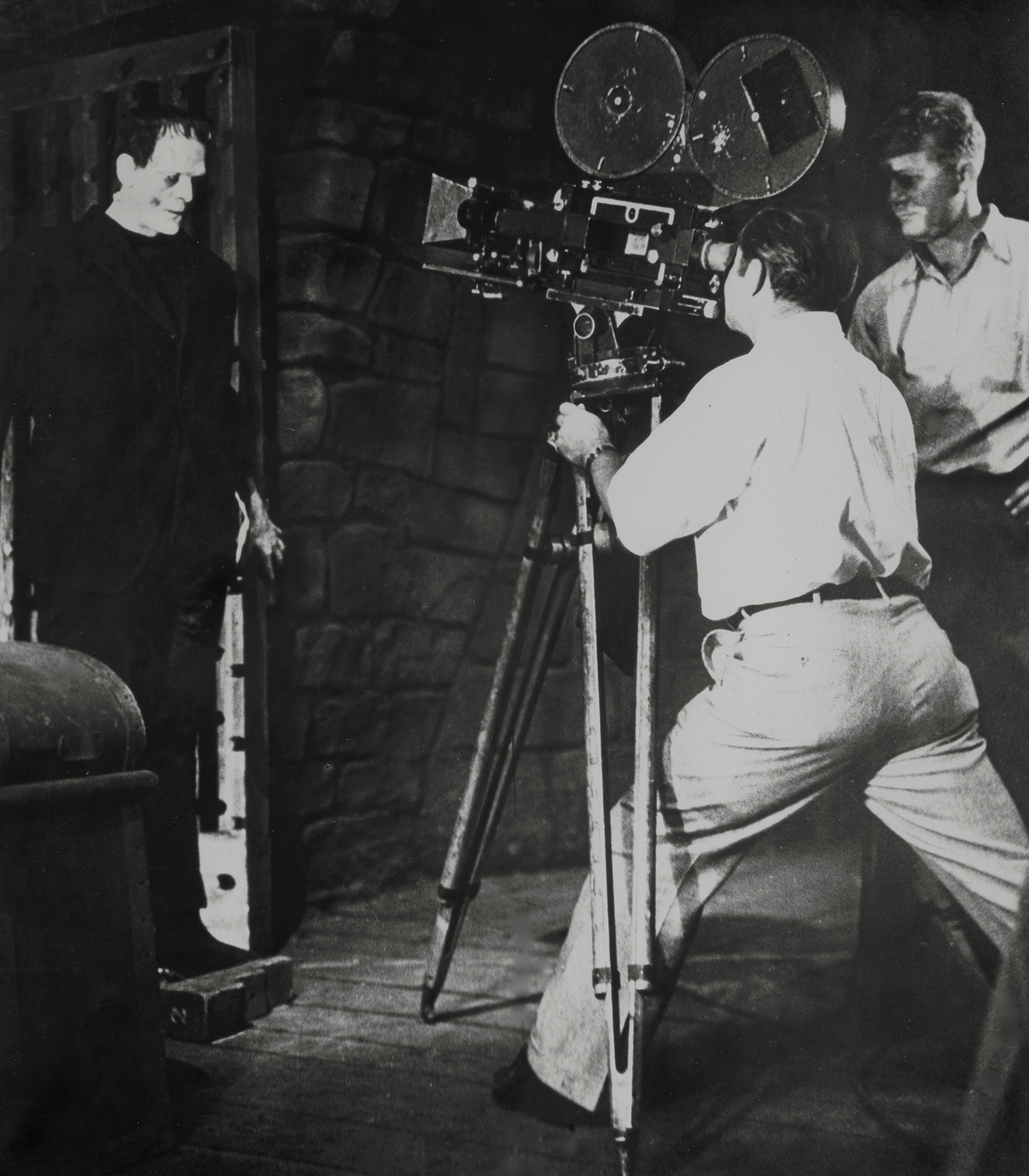

Director James Whale poses with a stand-in for Karloff.

Boris Karloff and Marilyn Harris as Little Maria.

U.K. export Whale not only brought his striking dramatic flair to the production, he brought two English actors who would forever be associated with the roles they created: Boris Karloff and Colin Clive. Karloff was a struggling forty-three-year-old bit player when Whale spotted him in the Universal commissary. With his deep-set, melancholy eyes; exceptional skill at pantomime; and a dental bridge that could be removed to form a hollow indentation in his cheek, Karloff—aided by Jack Pierce’s remarkable makeup—embodied Frankenstein’s creature so ideally that all subsequent characterizations owe him a debt. The squared-off forehead, the electrodes on either side of the neck, the too-short sleeves and weighted boots—none of these existed until Karloff’s menacing yet sympathetic monster appeared on the screen. When the film was released, Karloff became a legend in his own lifetime, and a horror-movie career was launched. “That poor dear abused monster,” he once said, “is my best friend.”

Often underappreciated is the equally dynamic performance of Colin Clive as Henry Frankenstein. Shelley’s scientist, she wrote, felt “an anxiety that almost amounted to agony” as he brought his creation to life, and Clive exhibits this quality throughout the film. An old knee injury had left the actor in chronic pain and with a crippling alcohol addiction. Using a touch of proto-Method acting, Clive tapped into his personal misery to give Frankenstein a dark ripple of manic torment that makes us believe he might actually rob graves to satisfy his scientific obsession. His iconic “It’s alive” scene is perfection. Upon seeing his creation move for the first time, Clive builds from a whisper to a frenzy in twelve seconds, taking his macabre giddiness to the edge of madness without quite going over the top. “Colin was electric,” remembered costar Mae Clark, who plays Frankenstein’s fiancée, Elizabeth. “When he started acting in a scene, I wanted to stop and just watch.” Like Karloff as the monster, no one else but Colin Clive could have embodied Frankenstein so memorably.

Released at a low point in the Great Depression, Frankenstein smashed theater records across the country. “People like the tragic best at those times when their own spirits are depressed,” a 1932 Motion Picture Herald article claimed, speculating that the economic crisis helped to make Frankenstein “one of the biggest box-office films in Universal history.”

Four years later, Universal had another hit on its hands with Bride of Frankenstein (1935), a unique blend of horror, sci-fi, and satire that proved to be one of the most successful sequels of all time. For Bride, James Whale pulled out all the stops, giving Karloff’s monster a rudimentary vocabulary and a taste for wine, women, and cigars. The Bride, played by Elsa Lanchester, became nearly as celebrated as the monster in a fraction of the screen time. Whale’s two classic Frankenstein films spawned a string of sequels and inspired dozens of later works, including Young Frankenstein (1974), The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), and Weird Science (1985).

KEEP WATCHING

MAD LOVE (1935)

THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1957)