1932

DIRECTOR: ERLE C. KENTON SCREENPLAY: WALDEMAR YOUNG AND PHILIP WYLIE, BASED ON A NOVEL BY H. G. WELLS STARRING: CHARLES LAUGHTON (DR. MOREAU), RICHARD ARLEN (EDWARD PARKER), LEILA HYAMS (RUTH THOMAS), BELA LUGOSI (SAYER OF THE LAW), KATHLEEN BURKE (THE PANTHER WOMAN), ARTHUR HOHL (MONTGOMERY), STANLEY FIELDS (CAPTAIN DAVIES), PAUL HURST (DONAHUE), HANS STEINKE (OURAN), TETSU KOMAI (M’LING)

Island of Lost Souls

PARAMOUNT • BLACK AND WHITE, 70 MINUTES

A shipwrecked man is held captive on an uncharted island where a renegade scientist conducts gruesome experiments on animals.

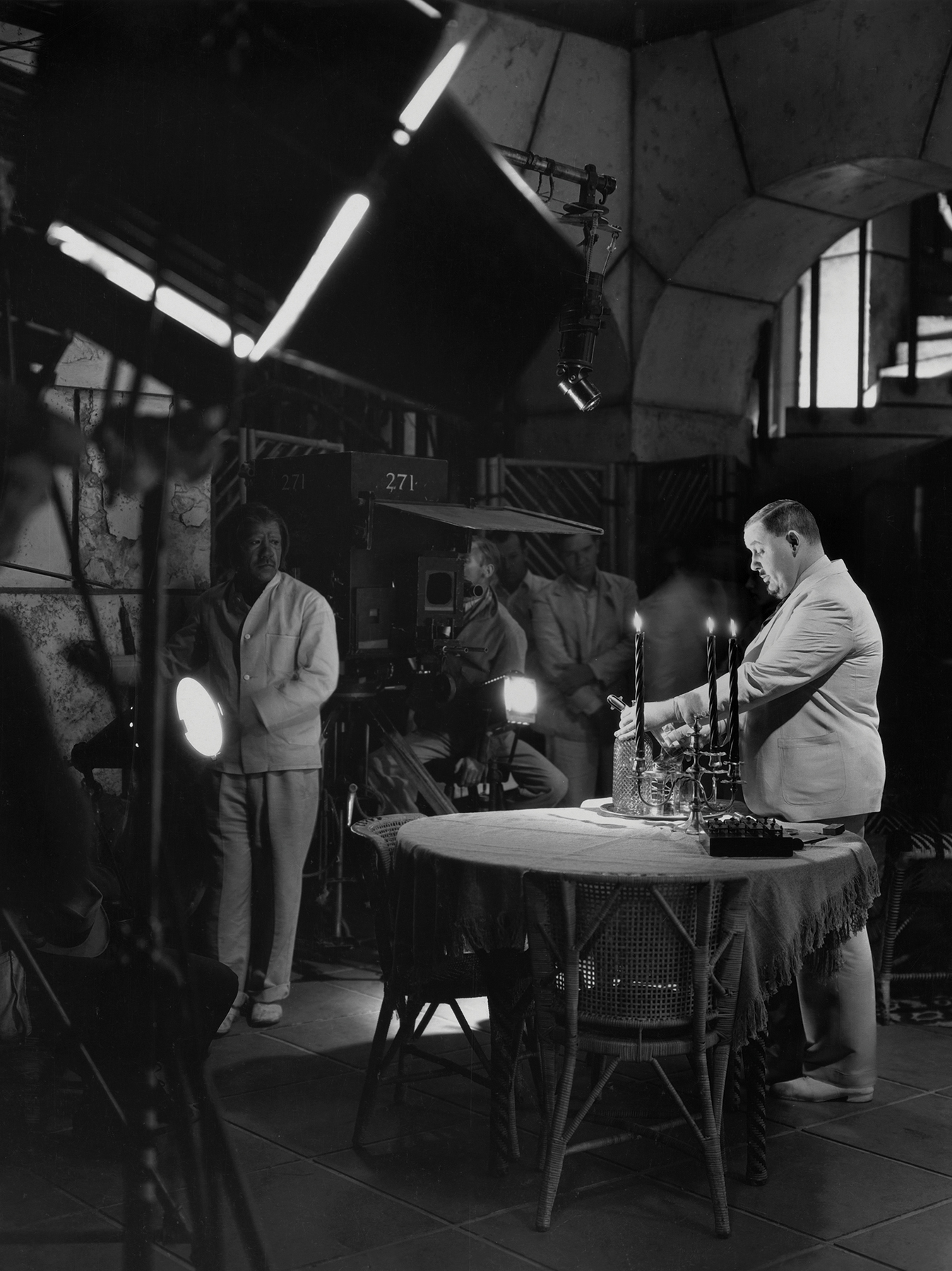

Charles Laughton on the set

“Horrible to the point of repugnance.” This was how the Los Angeles Times described Island of Lost Souls upon its release in January 1933. Much of the world agreed. England (and eleven other countries) banned the film entirely; several theaters in the United States and Canada showed censored versions with some of the most salacious moments edited out. Today, the film appears far less shocking to twenty-first century jaded eyes, but still retains its uniquely disturbing brand of terror.

In the early 1930s, before the Motion Picture Production Code was strictly enforced, a trend for graphic horror films swept Tinseltown. Studios competed with each other to push the limits of violence, sex, and freaky grotesquerie. Universal had Dracula and Frankenstein (both 1931), Warner Bros. made Doctor X (1932), Paramount released Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931), and MGM topped them all with the morbid Freaks (1932). When Paramount paid H. G. Wells $15,000 for the film rights to his 1896 novel The Island of Dr. Moreau, they hired a team of writers—and dependable studio director Erle C. Kenton—to turn the anti-vivisection parable into a full-blown screen nightmare.

In the book, Dr. Moreau attempts to transform wild animals into humans by experimental and painful surgeries, but his intentions are noble. In the film, Charles Laughton’s Moreau is a twisted sadist, an ice-cold psychopath with a God complex and a whip in his hand. He casually slices open his beast-men in a laboratory known as the House of Pain, and seems to enjoy their anguished howls. Laughton, who had made his Hollywood debut as a maniacal killer in Devil and the Deep (1932), embodies Moreau so fully that his riveting, restrained performance makes the film. “You can eat and get laughs with every bite, walk and have menace in it,” Laughton said of his technique. “It’s all in the interpreting of movements to give reality.”

The book’s minor mention of a puma woman becomes the Panther Woman in the movie, a major publicity gimmick for Paramount. Nineteen-year-old Kathleen Burke won the role after beating out 60,000 other women in a nationwide contest that sought a “feline type of beauty.” The Panther Woman raised the hackles of the censors by seducing the unwitting Edward Parker, played by Richard Arlen. Moreau plans to use Parker’s attraction to the female beast to mate human with animal; when that fails, he encourages one of his beast-men to mate with Parker’s innocent fiancée, Ruth (Leila Hyams). The implications of bestiality and rape are extreme even by today’s standards. The controversy these subjects caused fueled the case for self-censorship, leading the Production Code to adopt a stricter approval system in 1934.

A team of makeup experts headed by Wally Westmore transformed dozens of actors—including a fur-covered Bela Lugosi as the Sayer of the Law—into hideous mutations with pointed ears, hooves, and faces like hyenas. The “curiosities,” as Dr. Moreau refers to them in the Wells novel, are black, hairy, and always in shadows, while the island’s humans are clad in pure white, so bright they almost glow in the dark. Glorious black-and-white film is the perfect medium for a story about contrasts—and frightening similarities—between human and animal, civilization and nature, good and evil. The fog that naturally shrouded the filming location of Catalina Island only helps to blur the lines and create a misty netherworld where anything seems possible.

A decade before the film noir style popularized venetian blind–filtered strips of light, cinematographer Karl Struss streaked shadows across the faces of actors to create atmosphere. Struss, who had won an Oscar for F. W. Murnau’s silent drama Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), employs high-contrast lighting to ideal effect here, using tropical plants, latticework, and window shades to cast ominous silhouettes. Candlelight is used impeccably in a scene just before one of Moreau’s creatures attacks. The doctor blows out three candles, the room growing dimmer as each flame is extinguished until the only light source is the whites of his eyes gleaming in a pool of darkness. Without any dialogue or music, we know something sinister is about to happen.

Bela Lugosi as the Sayer of the Law

Richard Arlen and Leila Hyams in a promotional photo for the film

Despite several later attempts to adapt The Island of Dr. Moreau on film and television, Kenton’s Island of Lost Souls remains the classic screen version. As an early hybrid of horror and science fiction, it has inspired generations of filmmakers, from John Landis—who called the film “far more horrific than Frankenstein”—to Alex Garland, whose Ex Machina (2015), with its human-robot relationship, owes a great deal to Edward Parker and the Panther Woman.

KEEP WATCHING

MURDERS IN THE ZOO (1933)

CAT PEOPLE (1942)