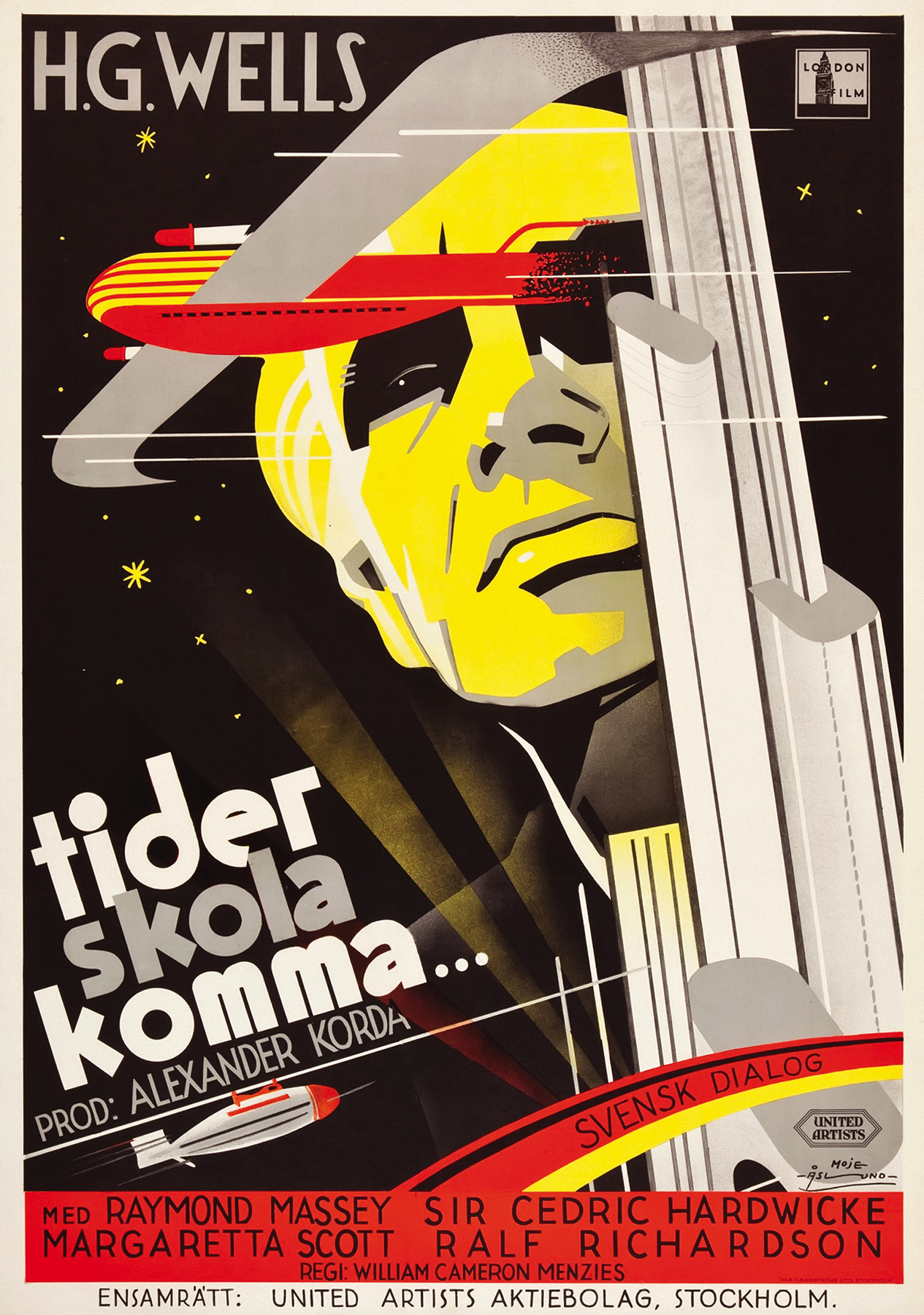

1936

DIRECTOR: WILLIAM CAMERON MENZIES PRODUCER: ALEXANDER KORDA SCREENPLAY: H. G. WELLS, BASED ON HIS NOVEL STARRING: RAYMOND MASSEY (JOHN CABAL/OSWALD CABAL), EDWARD CHAPMAN (PIPPA PASSWORTHY/RAYMOND PASSWORTHY), RALPH RICHARDSON (THE BOSS), MARGARETTA SCOTT (ROXANA/ROWENA), CEDRIC HARDWICKE (THEOTOCOPULOS), MAURICE BRADDELL (DR. HARDING), SOPHIE STEWART (MRS. CABAL), DERRICK DE MARNEY (RICHARD GORDON), ANN TODD (MARY GORDON)

Things to Come

LONDON FILMS/UNITED ARTISTS (BRITAIN) • BLACK & WHITE, 97 MINUTES

Between the years 1940 and 2036, a scientist—and later, his great-grandson—drive society on toward technological progress and eventual utopia.

William Cameron Menzies, Raymond Massey, and Pearl Argyle on the set

Things to Come, a bold, sweeping vision of the future, landed smack in the middle of the Great Depression like a missile from the moon. Between its post-holocaust barbarism, its fleet of advanced aircraft, and its streamlined super-cities, no one in 1936 knew quite what to make of it. Even today there is no other movie like it—only Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) comes close. A monumental collaboration between “father of science fiction” H. G. Wells, producer Alexander Korda, and director William Cameron Menzies, Things to Come was the most expensive British film ever produced when it was made, and remains an unforgettable entry in the sci-fi genre.

Futuristic science-fiction films were scarce in the 1930s and ’40s. One year after the stock-market crash of 1929, Fox released Just Imagine (1930), an ambitious sci-fi musical comedy set in the year 1980, and an epic box-office failure. In 1933, the studio repeated the formula with It’s Great to Be Alive, and the results were even more disastrous. Subsequently, most cinematic space-age sci-fi was relegated to cheaply produced serials like Flash Gordon (1936) until 1950—at least in Hollywood. In England, eminent filmmaker Alexander Korda and his London Films adapted the 1933 H. G. Wells book The Shape of Things to Come for the big screen; Wells himself even wrote the screenplay and supervised the production.

Right off the bat, Things to Come accurately predicts a second world war starting in 1940. Wells’s message comes through loud and clear via the words of scientist John Cabal (Raymond Massey): “If we don’t end war, war will end us.” By 1970, civilization is in tatters following a lengthy mega-battle that depletes the planet’s resources. The Wandering Sickness—pop culture’s first stab at a zombie apocalypse—befalls humankind, and soon Everytown (a stand-in for London) is governed by a makeshift warlord (Ralph Richardson). Menzies, who had already racked up an impressive list of credits as a production designer (and would win an honorary Oscar for Gone With the Wind [1939]), directs with an eye toward spectacle, as Wells packs the dialogue with his technocratic and socialist agendas. The result is a somewhat preachy but visually stunning work of art, augmented by Arthur Bliss’s majestic score.

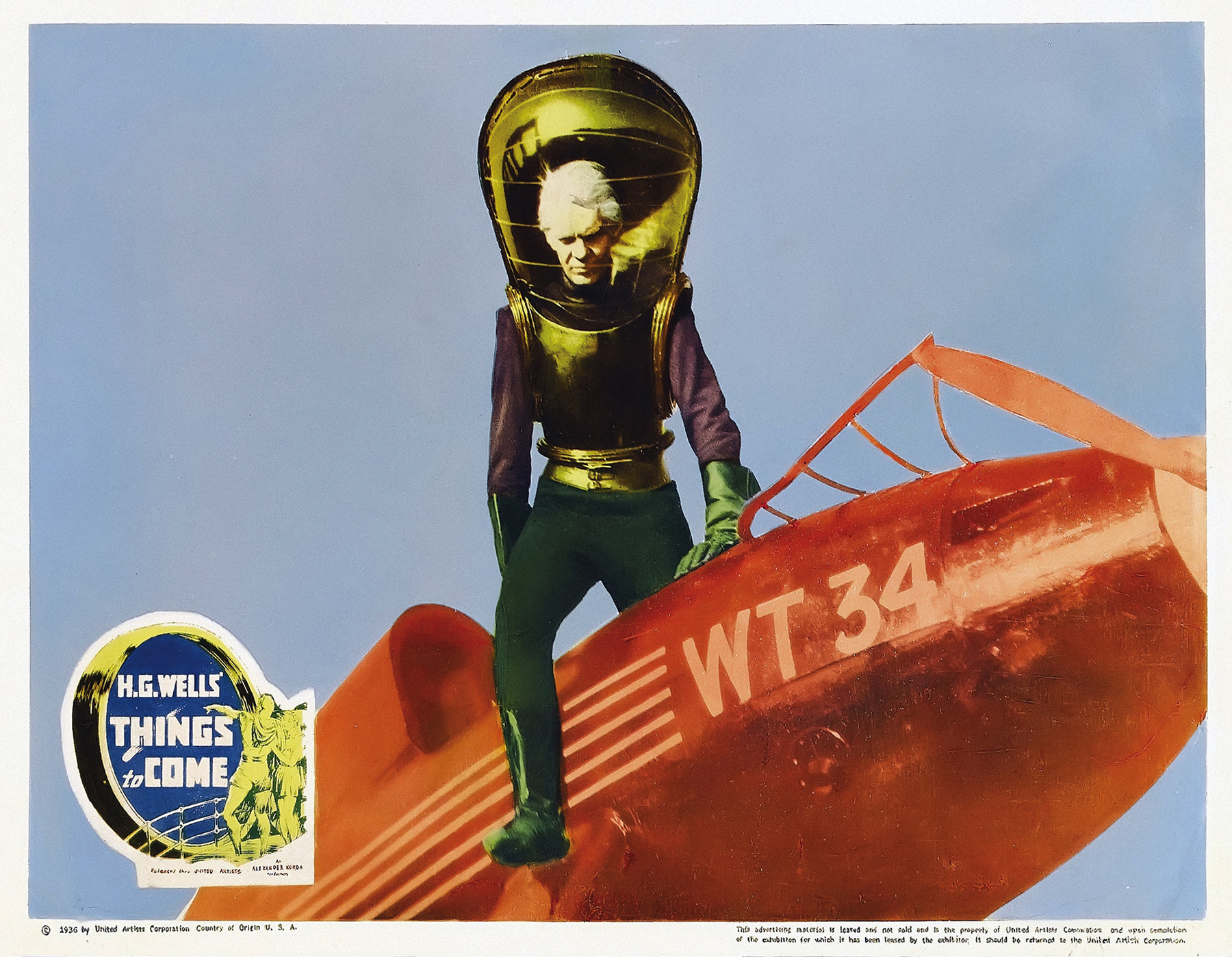

Raymond Massey as John Cabal

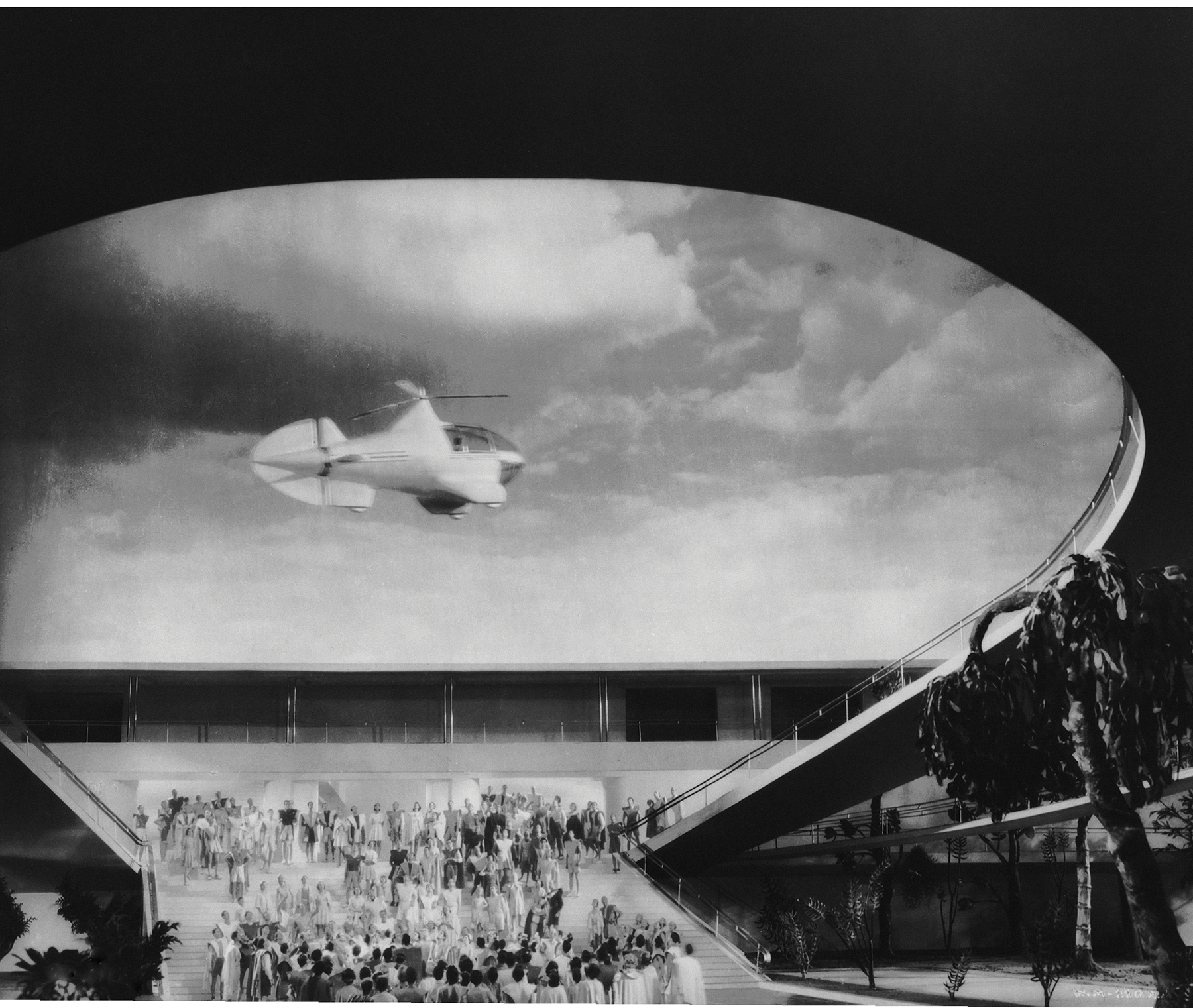

A personal aircraft in the year 2036

Fast forward to the year 2036, and the set design becomes truly astounding. Alexander’s brother Vincent Korda—with input from cinematographer Georges Périnal and Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy—expanded on 1930s moderne architecture to create an underground city that manages to look both retro and futuristic today. Menzies allows Korda’s gleaming art-deco utopia to fill the screen, overwhelming our senses with Wellsian touches like contemporary-looking TV sets, escalators, and personal helicopters. Stylistically, Things to Come could almost be a sequel to Metropolis, though Wells disliked Fritz Lang’s film. At one point, he even sent a memo to the staff advising: “Whatever Lang did in Metropolis is the exact opposite of what we want done here.” But the two films are linked by their dreamlike vistas of massive future cityscapes, and by the sheer audacity of their existence. Though the warm, human element is lacking in Things to Come, noble intentions prevail as Oswald Cabal, great-grandson of John (also played by Massey), exerts his level-headed control and, in the end, arranges for his daughter and her boyfriend to be sent to the moon.

The film’s tone of sleek confidence belies a great deal of behind-the-scenes tension between Korda, Menzies, and Wells, who fought for total control of the production, though he had no practical filmmaking experience. When Things to Come failed to make the desired impact, its writer and director each blamed the other. Wells privately considered Menzies “an incompetent director… a sort of Cecil B. DeMille without his imagination,” while Menzies wrote of the collaboration, “Damn that old fool Wells.” None of the film’s creative forces was entirely happy with the finished product, and it performed poorly at the box office. The Depression-battered public wasn’t ready for such a far-reaching vision—nor was it prepared for the dreary Wellsian future of an advanced but sterile civilization.

As much as Wells tried to avoid it, his film cannot escape comparisons to Metropolis. Yet Things to Come is prescient in many ways that Metropolis, for all its beauty, is not. Though it may not have predicted the future of society, the combined vision of Wells, the Kordas, and Menzies—with its plague of walking dead, giant flat-screen TVs, and post-apocalyptic anarchy straight out of a Mad Max movie—uncannily forecasted the future of entertainment.

KEEP WATCHING

LOST HORIZON (1937)

SKY CAPTAIN AND THE WORLD OF TOMORROW (2004)