1962

DIRECTOR: JOSEPH LOSEY PRODUCERS: MICHAEL CARRERAS, ANTHONY HINDS, AND ANTHONY NELSON KEYS SCREENPLAY: EVAN JONES, BASED ON A NOVEL BY H. L. LAWRENCE STARRING: MACDONALD CAREY (SIMON WELLS), SHIRLEY ANNE FIELD (JOAN), VIVECA LINDFORS (FREYA NEILSON), ALEXANDER KNOX (BERNARD), OLIVER REED (KING), WALTER GOTEL (MAJOR HOLLAND), BRIAN OULTON (MR. DINGLE)

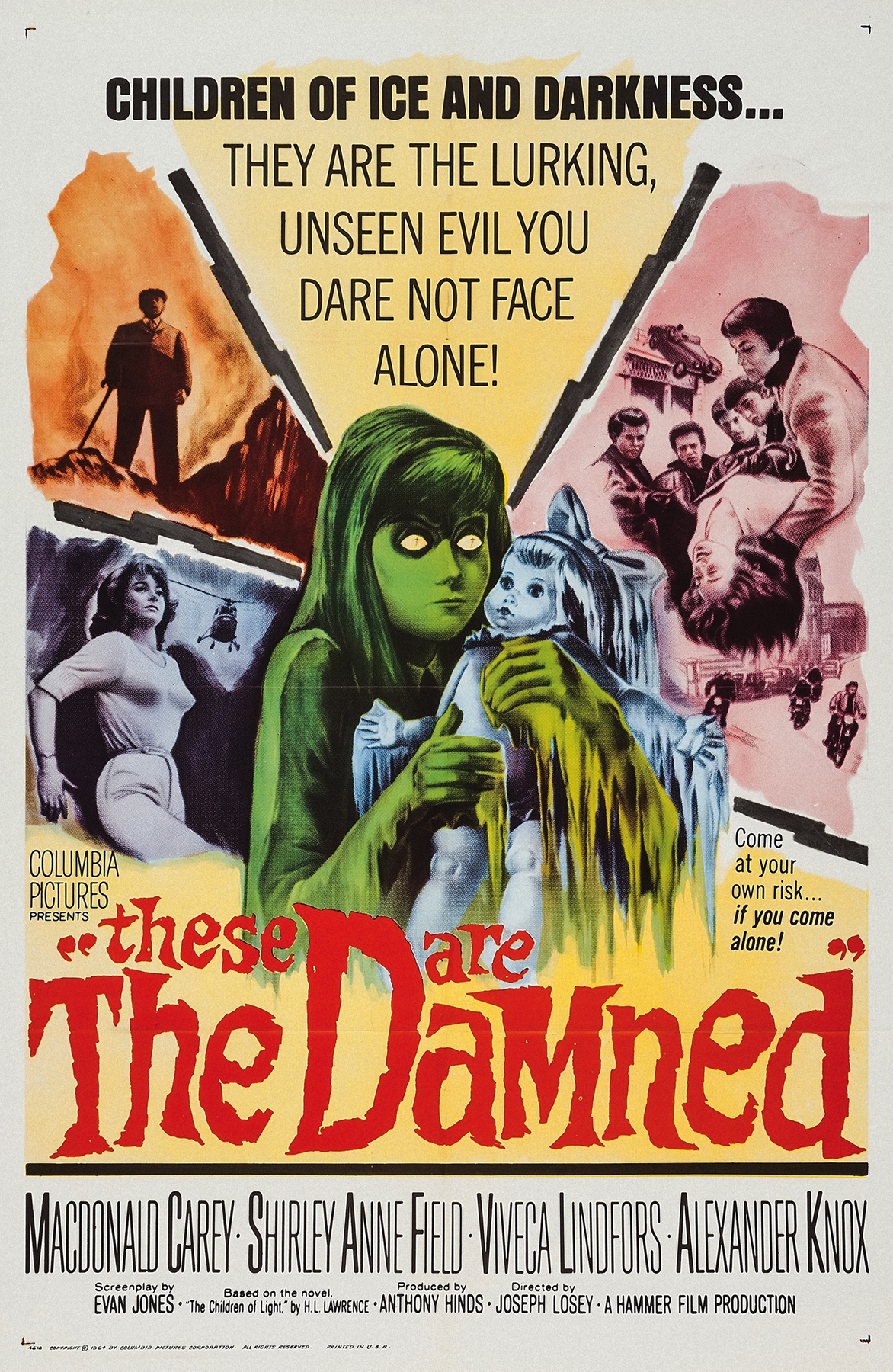

These Are the Damned

HAMMER FILMS/COLUMBIA • BLACK & WHITE, 87 MINUTES

In an English coastal town, the leader of a hoodlum gang chases his sister and her American lover into a secret underground encampment of quarantined children.

In the late 1950s and early ’60s, a spate of nuclear paranoia films appeared. On the Beach (1959), The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959), The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961), and Panic in Year Zero! (1962) presented doomsday scenarios more disturbing than any giant insects. One of the bleakest and most bizarre of this crop is These Are the Damned, a remarkable British sci-fi thriller by exiled American director Joseph Losey. Linking common street violence with destruction at the highest government level, Losey’s adaptation of H. L. Lawrence’s book The Children of Light mixes motorcycle gangs, love, and radioactive children to form a peculiar pastiche.

Filmed in the shabby seaside resort of Weymouth in the summer of 1961, one year before the Anthony Burgess novel A Clockwork Orange was published, These Are the Damned anticipates that book’s recreational ultra-violence with its Teddy Boys led by the unhinged King, played by Britain’s definitive bad boy Oliver Reed. Gloriously photographed in Hammerscope by Arthur Grant’s roving camera, the opening scenes both shock and entertain as King and his thugs savagely beat American tourist Simon to the swinging strains of “Black Leather Rock,” composer James Bernard’s infectious ode to violence (“Black leather, black leather, kill, kill, kill!”). King’s sister, Joan, throws the gang a curve when she hops aboard Simon’s boat and they escape to an isolated cliffside cottage inhabited by a sculptress named Freya, who just happens to be the mistress of Bernard, a scientist conducting a dreadful secret experiment nearby.

As the disparate, doomed characters intersect, the landscape becomes more barren, and the unpredictable story winds through Weymouth to the edge of the world. There, beneath perilous cliffs overlooking an endless sea, Bernard and his government officials hold a group of irradiated kids in an underground lair, where they prepare them for nuclear Armageddon via closed-circuit TV. They are breeding “a new kind of man,” Bernard says, to withstand “the conditions which must inevitably exist when the time comes.” With chilling efficiency, the government is raising a race to populate the post-apocalyptic world they believe to be unavoidable. When Joan, Simon, and King follow the children into their hideout, they not only seal their own fates but unknowingly damn the young victims as well.

Joseph Losey, who had relocated to England after being blacklisted by Howard Hughes at RKO for alleged Communist sympathies, infused These Are the Damned with his anti-establishment sensibilities. His objective in making this “emotional plea against the destruction of the human race,” he said, was “to unsettle people, to force them to think.” Losey pulls no punches; his vicious street thugs are more human than the men in suits, “because they don’t know what they’re doing,” the director noted, “and they are not responsible for what they are. The others are perfectly conscious, and they have no innocence.”

While he may not be innocent, Bernard is apparently a decent man—he treats the children kindly and seems to have their best interests at heart—making his character all the more unsettling. If he’s not the bad guy, who is? The only true villains in this tale, Losey implies, are the bomb and the system that produced it. Viveca Lindfors’s Freya (named for Freyja, a Norse fertility goddess), is the film’s moral core, embodying the pure impulses of art, love, and passion. She, too, is ill-fated once she learns of Bernard’s experiments. Her sculptures resembling immolated birds loom ominously in the background, foreshadowing the helicopters that swoop down on the children in the end. Symbols of oblivion hover in virtually every scene of the film.

Hammer Films, a studio known for horror (The Curse of Frankenstein [1957]) and later excursions into sci-fi (Quatermass and the Pit [1967]), edited nearly twenty minutes from the film and postponed distributing it until 1963 in the United Kingdom, where it was known as The Damned. It didn’t reach American theaters until 1965, possibly because, as Variety’s review speculated, “its subject or its director may have, in 1963, been considered too controversial.” Today it has a small but fervent cult following. These Are the Damned is a work of art with an agenda—even a grudge—yet it conveys its message so poetically that the result is more profound than preachy. It is a movie steeped in wild abandon, as if every moment might be its last on Earth.

Alexander Knox as Bernard, the keeper of the children

The Teddy Boys attack Macdonald Carey as Shirley Anne Field looks on.

KEEP WATCHING

ON THE BEACH (1959)

CHILDREN OF THE DAMNED (1964)