1965

DIRECTOR: JEAN-LUC GODARD PRODUCER: ANDRÉ MICHELIN SCREENPLAY: JEAN-LUC GODARD STARRING: EDDIE CONSTANTINE (LEMMY CAUTION), ANNA KARINA (NATACHA VON BRAUN), AKIM TAMIROFF (HENRI DICKSON), HOWARD VERNON (PROFESSOR VON BRAUN), LÁSZLÓ SZABÓ (THE ENGINEER), MICHEL DELAHAYE (ASSISTANT TO PROFESSOR VON BRAUN)

Alphaville

PATHÉ CONTEMPORARY FILMS (FRANCE) • BLACK & WHITE, 99 MINUTES

A secret agent travels to a distant galaxy to destroy the inventor of a mind-controlling supercomputer.

Watching Alphaville is like traveling to another planet without ever leaving the ground. One of the most unconventional science-fiction movies ever made, Alphaville depicts the future as only French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard could have imagined it: a retro 1940s film noir colliding into a dystopian technocracy—or George Orwell’s 1984 meets Dead Reckoning (1947) starring Humphrey Bogart. As he had done with the genres of crime (Breathless [1960]), musical (A Woman Is a Woman [1961]), and war (Le petit soldat [1963]), Godard deconstructs the expected science-fiction tropes and scrambles them, creating a new style that has left an indelible mark on cinema.

Alphaville was originally conceived by Godard as Tarzan versus IBM, a pulp-fiction mash-up concerning trench-coated, gun-toting secret agent Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine). Caution is sent undercover to Alphaville, the capital city of a distant galaxy, to track down a fellow agent, Henri Dickson, and eliminate the evil Professor von Braun. Godard fashions film-noir conventions—night scenes, neon lights—into a dark urban landscape ruled by the cold logic of von Braun’s computer, Alpha 60. When Lemmy falls for von Braun’s beautiful but brainwashed daughter, Natacha (Anna Karina), he must not only destroy her father and the computer, but rescue her mind from the machine’s control. Typical of his off-the-cuff style, Godard shot the film in a few weeks, spinning the story as he went along. “We never had a script,” recalled Karina, the director’s muse, favorite actress, and wife at the time.

Godard’s special-effects budget was nonexistent. His city of the future is a thinly disguised Paris of 1965, a setting that offers a built-in social comment. “I set it in the future, but it’s really about the present,” Godard told a reporter in 1966. “The menace is already with us.” In keeping with the bare-bones effects, Lemmy travels through space simply by driving his Ford Galaxie. Godard apparently couldn’t even afford a Galaxie, since the car is actually a Mustang posing as a Galaxie—but that’s beside the point. The director weaves a certain magic spell that makes Alphaville compelling, a neon-throbbing ambience heightened by the melodramatic strings of Paul Misraki’s original score. As Raoul Coutard’s camera roams the corridors of modern buildings, it captures an array of circles, wheels, and spirals, while Alpha 60—depicted as a halogen orb—bellows cryptic philosophies in a croaking mechanical voice: “Time is like a circle which turns endlessly.” Godard’s postmodern nightmare was a statement “against the destruction of thought and emotion by machines,” he said, and was strongly influenced by the Orson Welles drama The Trial (1962).

Godard pioneered a language of communicating ideas through pop-culture touchstones, inspiring a generation of directors (Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson) to follow suit. Like most of the auteur’s early films, Alphaville is brimming with pop references: Caution reads Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep; von Braun’s real name is “Nosferatu,” as in F. W. Murnau’s 1922 vampire film; Professors Eckel and Jeckel recall the cartoon magpies Heckle and Jeckle. Even Alphaville’s hero, Lemmy Caution, is plucked from a series of detective novels by British author Peter Cheyney, which had been adapted into several French movies with titles like This Man Is Dangerous (1953) and Women Are Like That (1960).

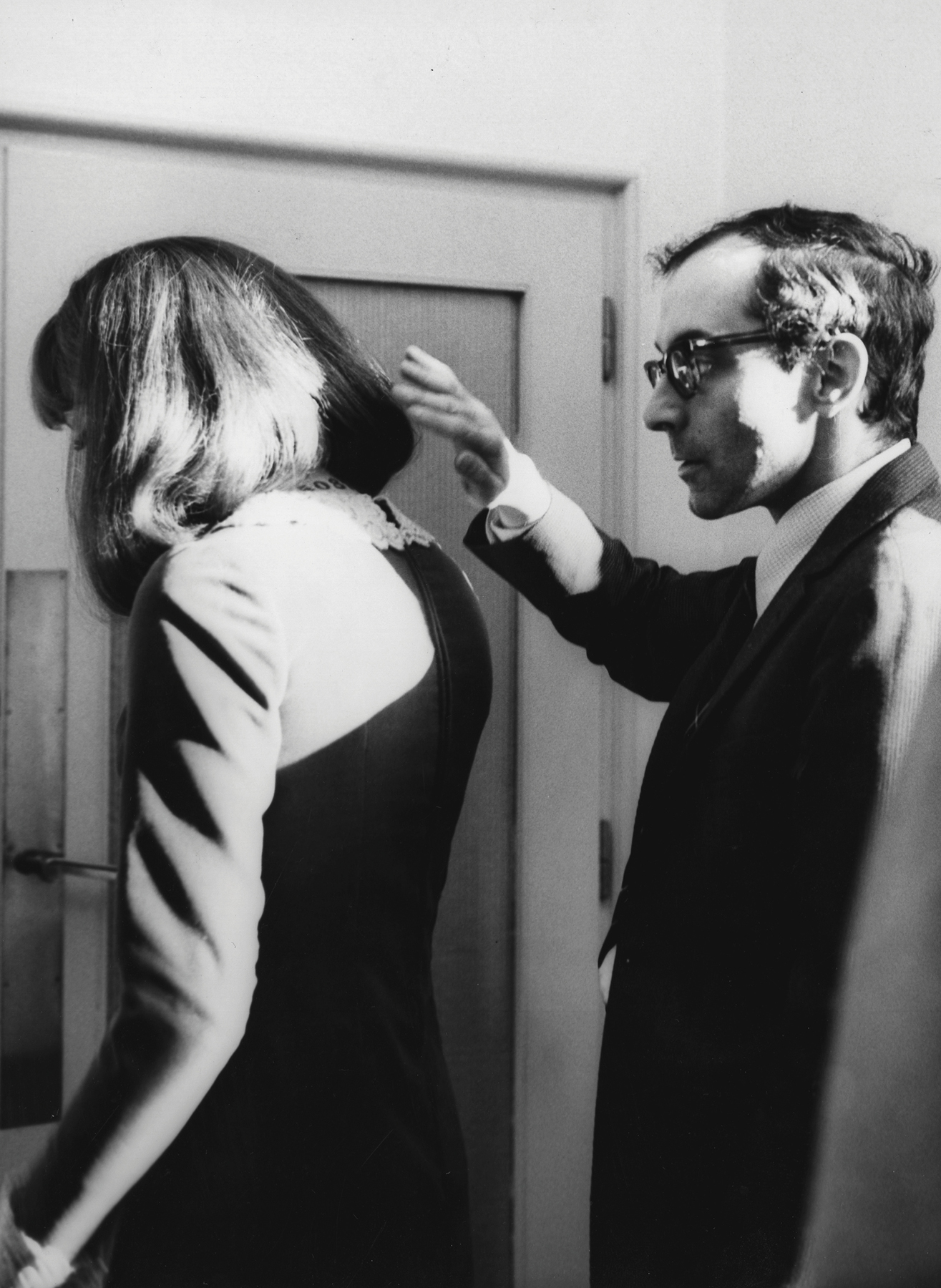

Jean-Luc Godard directs his wife, Anna Karina.

Akim Tamiroff and Eddie Constantine

Caution, a throwback to the past, carries his old-fashioned flashbulb camera and vintage cigarette lighter into the dismal future like beacons of hope. Memory and nostalgia, Godard seems to say, are powerful tools to fight a system that outlaws the words “love” and “conscience,” and publicly executes anyone who displays emotion. Young women—under the male-dominated rule of Professor von Braun and his computer—have become passive, robotic sex objects. To break her dependence on the computer, Lemmy reads Natacha surrealist poems and tells her to “think of the word love.” This is Godard at his most idealistic.

In 1965, Alphaville opened the New York Film Festival and won top prize at the Berlin International Film Festival. As a comic-book concoction of action, noir, and sci-fi woven together with a thin thread of winking satire, it had quite an impact. Though Alphaville’s most obvious descendant is Ridley Scott’s sci-fi-noir Blade Runner (1982), its surreal dystopian atmosphere and undercurrent of irony laid the groundwork for a slew of other movies, including 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Brazil (1985). Ultimately, Jean-Luc Godard would embrace the technology he once opposed. In 2010, Godard released Film socialisme, a feature he shot using digital video and a cell phone, edited with content pulled from the Internet.

KEEP WATCHING

FAHRENHEIT 451 (1966)

SECONDS (1966)