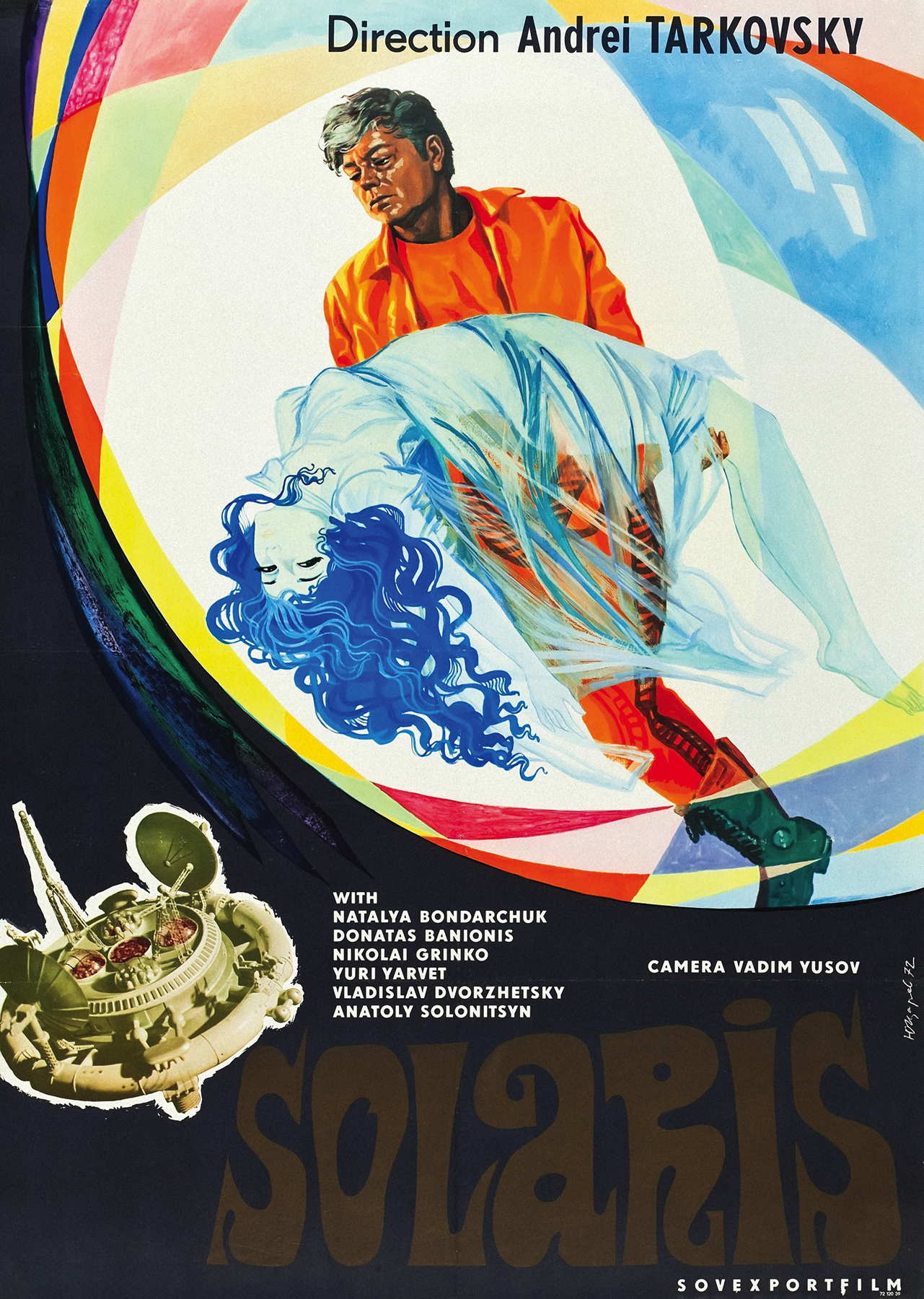

1972

DIRECTOR: ANDREI TARKOVSKY PRODUCER: VIACHESLAV TARASOV SCREENPLAY: FRIDRIKH GORENSHTEIN AND ANDREI TARKOVSKY, BASED ON A NOVEL BY STANISLAW LEM STARRING: NATALYA BONDARCHUK (HARI), DONATAS BANIONIS (KRIS KELVIN), JÜRI JÄRVET (DOKTOR SNAUT), VLADISLAV DVORZHETSKY (ANRI BERTON), NIKOLAY GRINKO (NIK KELVIN), ANATOLIY SOLONITSYN (DOKTOR SARTORIUS)

Solaris

MOSFILM (RUSSIA) • COLOR/BLACK & WHITE, 166 MINUTES

A psychologist encounters a past love when he is sent to investigate reports of unusual phenomena aboard a space station.

Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky once observed that cinema artists can be divided into two categories: those who try to re-create the world in which they live, and those who create their own world. “Those who create their own world,” the director said, “are usually poets.” This is certainly true of Tarkovsky, a visual poet who created a uniquely mesmerizing world in Solaris, his third film and first venture into science fiction. Employing slow tracking shots, meditative pauses, and hallucinatory imagery, Tarkovsky transformed Polish author Stanislaw Lem’s 1961 outer-space novel Solaris into his own deeply internal celluloid dream.

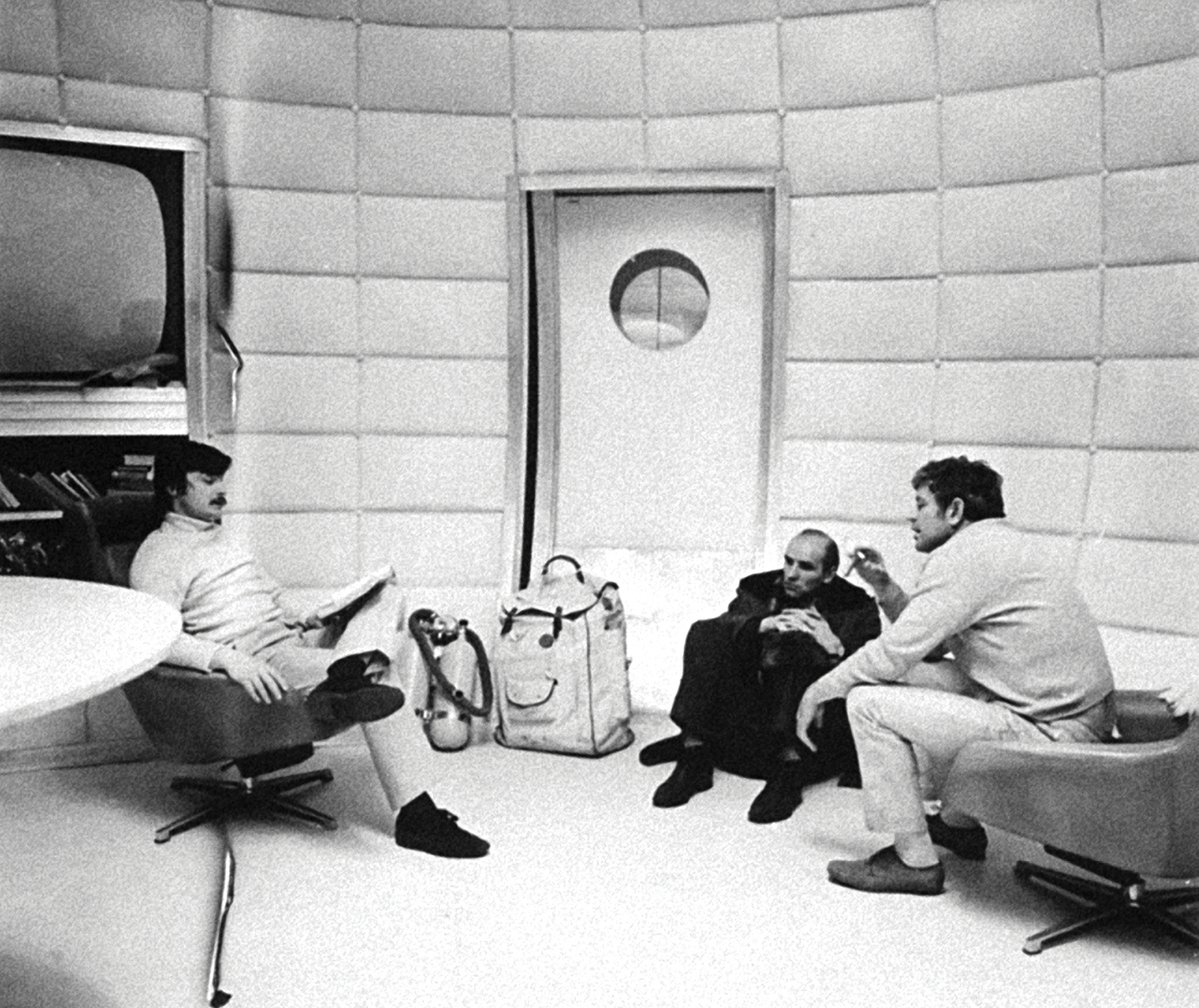

Often considered Russia’s answer to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Solaris was more likely intended by Tarkovsky to be the anti-2001. He felt the Kubrick epic was “phony” and “sterile,” and sought to use the science-fiction genre as a means of exploring the human psyche. To this end, Tarkovsky steered clear of special effects—an artistic decision that was also necessitated by the budgetary constraints imposed by Mosfilm, the Soviet film bureau. Compare Kubrick’s dazzling, whirling spacecraft to the dilapidated space station in Solaris, its dim, cavernous hallways evoking only emptiness. Instead of the vibrant spacesuits worn by 2001’s astronauts, Kris Kelvin sports a T-shirt and rumpled leather jacket as he wanders the space-station corridors unshaven. Played to disheveled, disillusioned perfection by Lithuanian star Donatas Banionis, Kris is a reluctant traveler longing for the comforts of Earth.

Aboard the lonely galactic outpost—inhabited only by two other scientists—Kris encounters something more disturbing than aliens: a being conjured by the strange sea on the nearby planet of Solaris. Tarkovsky introduces the beautiful visitor like a heavenly apparition, using back-lighting and a startling close-up that marks a shift from black-and-white to color. The “guest” is soon revealed to be Kris’s dead wife, Hari, who had committed suicide years before. Is she human, a ghost, an extraterrestrial, or a figment of his imagination? No clear answers are offered. She seems to be a manifestation of conscience that grows more real with time.

Director Andrei Tarkovsky, Anatoliy Solonitsyn, and Donatas Banionis

Donatas Banionis as Kris Kelvin

As the Solaris ocean roils in unearthly hues of purple and orange, Hari develops human emotions and Kris rekindles his love for her. For Tarkovsky, the sci-fi scenario was a tool for pondering the nature of relationships, memories, and desires. In one scene, Kris and Hari float together in a weightless embrace while the space station changes its orbit. This wordless expression of visual poetry—the film’s only real special effect—is sharply contrasted by the harrowing (and also wordless) sequence that follows: Hari’s suicide by ingesting liquid oxygen. More phantom than mortal, Hari appears to die but is reborn in a writhing, agonizing process resembling a seizure. Actress Natalya Bondarchuk remembered Tarkovsky’s words as he directed her resurrection. “She is being reborn through pain,” he told her. “She is developing internal organs. The corpse is returning to life through death.” Tarkovsky later had to fight to keep this scene when Soviet authorities ordered it cut from the film due to its erotic undertones.

Solaris premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1972, where it was awarded the Grand Prix Spécial du Jury. When a poorly dubbed and severely edited version (cut from 166 minutes to 132) finally appeared in the United States in 1976, audiences were nonplussed. “Obviously it is impossible to judge the pace, the rhythms, and the clarity of a film that is cut nearly in half [sic],” wrote the New York Times. “It is like a fresco partly eaten away by rising damp.” Eventually, the film was seen in its entirety and appreciated as a classic. In 2002, Solaris was updated by director Steven Soderbergh in a shorter, more commercially appealing form starring George Clooney and Natascha McElhone. Soderbergh whittled the story down to its emotional core, yet kept the introspective tone of the original film and novel.

As much a heartrending drama, a fantasy, and a study in psychological horror as it is a science-fiction epic, Andrei Tarkovsy’s Solaris defies classification. It is a challenging film—plodding, ambivalent to the wonders of space, more concerned with atmosphere than action. But once experienced, its haunting world is not easily forgotten. One famous fan, Japanese director Akira Kurosawa, praised Solaris for its frightening vision of the future. “Just where is scientific progress leading mankind?” Kurosawa wrote. “This film manages to capture perfectly the sheer fearfulness. Without it, science fiction becomes mere fancy.”

KEEP WATCHING

STALKER (1979)

CODE 46 (2003)