1982

DIRECTOR: RIDLEY SCOTT PRODUCER: MICHAEL DEELEY SCREENPLAY: HAMPTON FANCHER AND DAVID PEOPLES, BASED ON A NOVEL BY PHILIP K. DICK STARRING: HARRISON FORD (RICK DECKARD), RUTGER HAUER (ROY BATTY), SEAN YOUNG (RACHAEL), EDWARD JAMES OLMOS (GAFF), M. EMMETT WALSH (BRYANT), DARYL HANNAH (PRIS), WILLIAM SANDERSON (J. F. SEBASTIAN), BRION JAMES (LEON KOWALSKI), JOE TURKEL (DR. ELDON TYRELL)

Blade Runner

WARNER BROS. • COLOR, 117 MINUTES (2011 “FINAL CUT”)

A detective in 2019 Los Angeles becomes romantically entangled with one of the illegal androids he is assigned to find and destroy.

Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965) may have initiated the merging of futuristic science fiction with film noir, but Ridley Scott took the hybrid to breathtaking new heights with Blade Runner, arguably the most extraordinary vision of the future captured on film since Metropolis (1927). Eclipsed by E.T., Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Rocky III, and Poltergeist on its first release in the summer of 1982, Blade Runner spent years as a misunderstood failure before ultimately being recognized as “the Casablanca of science fiction.”

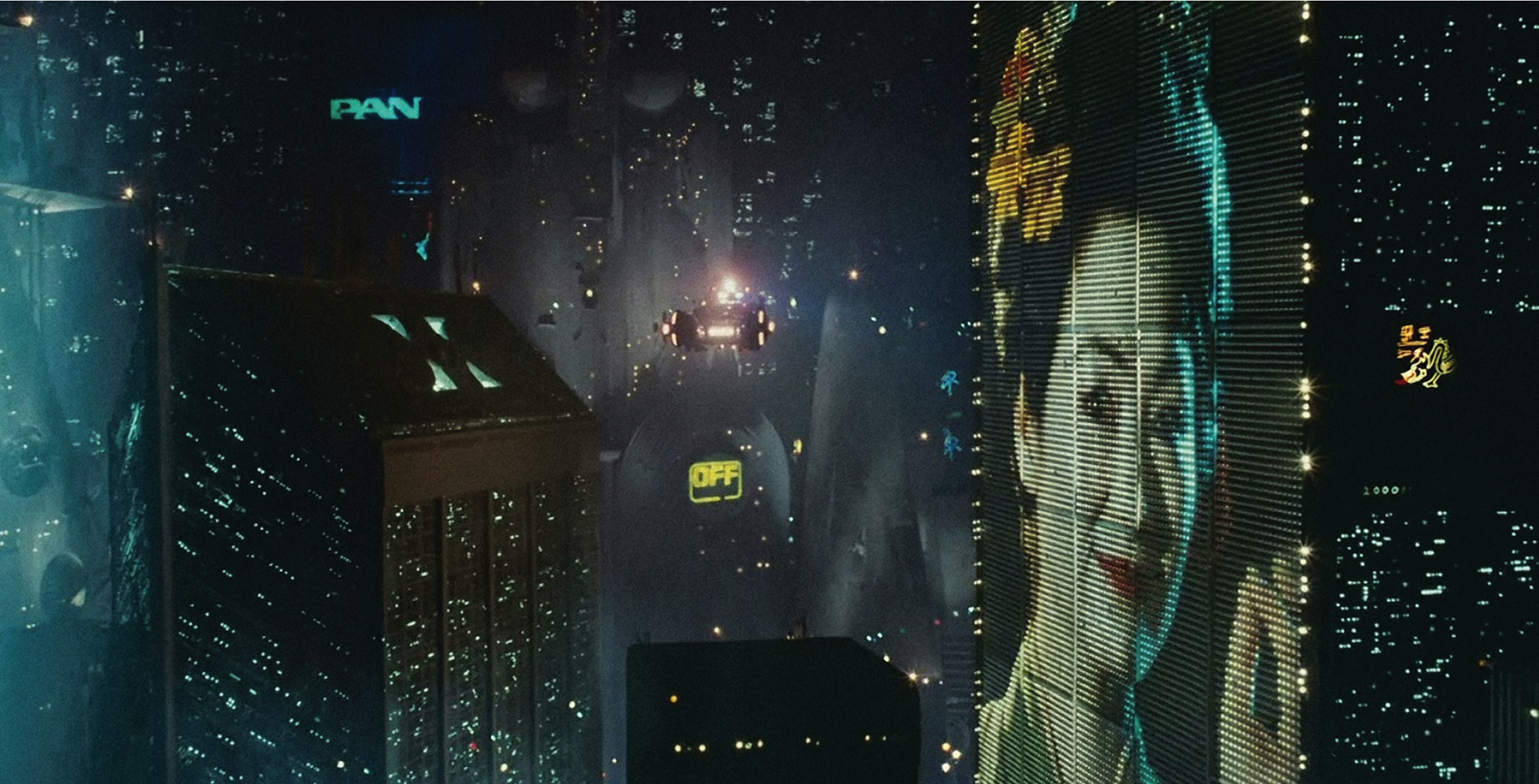

Originally called Dangerous Days, the movie began as Hampton Fancher’s loose adaptation of the 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick. When Alien (1979) director Ridley Scott jumped on board, he embarked on his dream project: an optically stunning dystopian film noir. Scott—with the help of director of photography Jordan Cronenweth, “visual futurist” Syd Mead, and effects guru Douglas Trumbull—created a future Los Angeles so distinct it’s a vital character in the film. A dense urban wasteland awash with neon and smog, the L.A. of Blade Runner is lit up with Asian advertisements and drenched in acid rain, “like Hong Kong on a bad day,” as Scott said. Occasionally, sunlight streams in through skyscraper windows like liquid gold as the synth-heavy Vangelis score sets a sensuous, melancholy mood.

The smoke, rain, and darkness—all of which Scott later admitted he used to disguise the inadequacy of the back-lot sets—made for a shooting experience so notoriously miserable that the crew rechristened the film “Blood Runner.” To novice actress Sean Young, Scott was a taskmaster, reportedly shooting twenty-six takes of her line “Do you like our owl?” because she didn’t pronounce “owl” precisely as he wanted. Harrison Ford was equally disgruntled. “It was a bitch working every night, all night long, often in the rain,” said Ford. But the oppressive atmosphere not only gives the film an unforgettable aesthetic, it makes an appropriate backdrop for the story’s hero. Rick Deckard, like the city, has seen better days. He’s a burned-out ex–blade runner forced to hunt down and kill a group of lifelike androids known as replicants. One of them, Young’s Rachael (who looks like a synthetic blend of Vivien Leigh and Hedy Lamarr), touches Deckard with her un-replicant-like sensitivity.

“One of the ironies of the film,” Ford observed, “is that this dead, dull man is revived by something that he knows is a fraud. But the emotions this fraud incites—the memories it provokes—are sufficient to create a real experience.” An understated screen actor, Ford was selected by Scott for his Bogart-like antihero quality. “Harrison Ford possesses some of the laconic dourness of Bogey, but he’s more ambivalent, more human,” the director said. But is Deckard human or a replicant? The film implies the question without answering it. Rutger Hauer’s smoldering performance as replicant Roy Batty juxtaposes Deckard’s icy detachment. Batty is vibrant, poetic, and on fire with emotion, expressing a very human sorrow that all of his memories “will be lost in time, like tears in the rain.”

Sean Young as Rachael

To please the public (and the film’s investors), Scott tacked on some voiceover narration by Ford and a happy ending—additions he would soon realize were unnecessary. These were later cut in subsequent versions, but not before the original sharply divided audiences and critics. Of the 1982 premiere, Hauer said, “It was as if the audience had been split with a razor.” People either loved Blade Runner or loathed it. Yet the film’s smoky urban art direction—referred to by the filmmakers as “retro deco” or “trash chic”—would dominate the look of the 1980s, from TV commercials to music videos on MTV. Its impact on cinema is immeasurable; movies as varied as Brazil (1985), The Fifth Element (1997), and Batman Begins (2005) owe a debt to Scott’s vision.

Ridley Scott directs Rutger Hauer as Roy Batty

Daryl Hannah as Pris, an outlaw replicant

Co-screenwriter David Peoples believes Blade Runner resonates because it poses big questions. “What exactly makes us human beings or not human beings? Are we people because we have memories? That is the underlying question of the film. And it’s not answered and not answerable,” stated Peoples in 2007. As we inch ever closer to the future depicted in the film, its delayed popularity gains greater momentum. In 2017, Scott’s long-dreamed-of sequel finally became a reality with Blade Runner 2049, directed by Denis Villeneuve. This time, Ford’s Deckard is pursued by a new blade runner (Ryan Gosling) in an even more polluted Los Angeles.

KEEP WATCHING

AKIRA (1988)

DARK CITY (1998)