BATTLEFIELD COMMUNICATION WAS one of the greatest problems for commanders of this period, especially as the size of battlefields grew and it was now virtually impossible for commanders to see everything for themselves. They increasingly had to rely on corps commanders to follow instructions, and these instructions had to be communicated.

Pre-battle briefings were an obvious requirement and could be given in person, but other means were required to issue further orders when needed, as the situation on the battlefield changed, sometimes rapidly. Napoleon used a Chief of Staff, to whom he provided a generalised version of his plans. The Chief of Staff’s role was to interpret these wishes and to issue specific orders to commanders to achieve the task. For the past fifteen years Marshal Louis Berthier had performed this role brilliantly, but when Napoleon returned from Elba, Berthier died, mysteriously falling from an upstairs window – whether suicide or murder has never been established. In Berthier’s absence, Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult was given the role, one he was not overly familiar with and which he performed only adequately. The Prussian army ran a similar system, with Gneisenau serving as Chief of Staff to Marshal Blücher. These orders were produced and copied for all relevant commanders, and then aides-de-camp or cavalrymen provided as letter parties rode off with them at break-neck speed to find their intended recipient – not an easy task in the heat and smoke of battle. It was often necessary to send at least two copies of the message to its recipient by separate messengers to ensure its safe arrival, as many messengers were struck down en route. Indeed, there are many twists in the story of the Waterloo campaign, and many of these centre on the failure of orders to arrive or on significant delays in orders arriving.

Date of production:

1815

Location:

Apsley House, London, UK

Wellington, however, chose a more direct method, giving verbal orders directly to commanders or writing orders himself to speed up the system and also to ensure there was no misunderstanding. For this purpose he had requested the holsters on his saddle to be modified to allow him to carry writing implements. Using pads of goat skin, Wellington hastily pencilled his orders and despatched an aide to carry them to their recipient.

Amazingly, four of these notes still survive.

The first shown here was presumably sent to the Earl of Uxbridge and read:

We ought to have more of the cavalry between the two high roads. That is to say three brigades at least besides the brigade in observation on the right, & besides the Belgian cavalry & the D. Of Cumberland’s Hussars. One heavy & one light brigade might remain on the left.

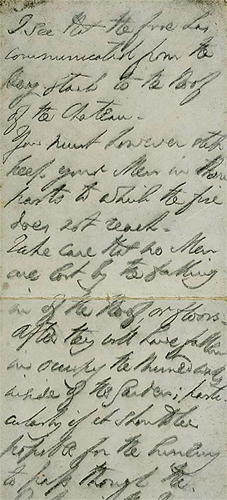

The second is perhaps the most famous, giving advice on defending the farm at Hougoumont while it was on fire. It reads:

I see that the fire has communicated from the haystack to the roof of the château. You must however still keep your men in those parts to which the fire does not reach. Take care that no men are lost by the falling in the roof, or floors. After they will have fallen in, occupy the ruined walls inside of the garden; particularly if it should be possible for the enemy to pass through the embers in the inside of the house.

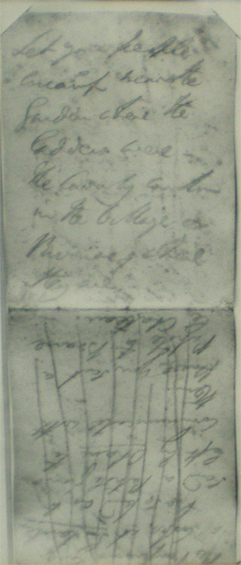

A third exists, which actually has two messages on it. The first reads:

Let your people encamp near the garden where the ladders were. The cavalry canton in the village or bivouac where they are.

The second, which has been struck through, having presumably been despatched to Uxbridge previously, reads:

The Prussians have a corps at St Lambert. Be so kind as to send a patrole from our left by Ohain to communicate with them. Have you sent a patrol to Braine Le Chateau[?]