CHAPTER 11

Untangling the Tune from the Accompaniment

A lot of the emotional impact that music has on us comes not from the melody itself but from the way it is harmonized with other notes. A change in harmony can completely change the emotional power of a tune. But as the accompanying notes and the tune are all happening at the same time, why don’t we get them mixed up? How does our hearing system work out that this note is part of the tune and that note is part of the harmony?

We can always spot which part of the music is the tune, even if the melody is new to us and there are lots of other accompanying notes going on at the same time.* Our ability to do this is extremely impressive when you realize that a computer would find it impossible in all but the simplest cases. The human brain outstrips the computer in identifying melody because it’s extremely good at something called grouping.

“But what’s the big deal?” you might say. “The tune’s always obvious, isn’t it?”

Er—no. The tune just seems obvious because we are so very good at spotting it and separating it out from the background notes even if all the notes involved have the same timbre and loudness. In a harmonized piece of music there are so many possible tunes going simultaneously that our to ability spot the one the composer had in mind is astonishing.

In fact, as we shall soon see, the number of options we have to choose from is staggering, even if you pick just a few seconds of a simple tune with a very uncomplicated harmony.

Yes—it’s “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep” time again…

Let’s say I have hired some flute players to entertain us by playing my latest masterpiece, an arrangement of the first line of “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep” for four flutes.

Our most expensive flautist will play the tune:

C5 C5 G5 G5 A5 B5 C6 A5 G5.

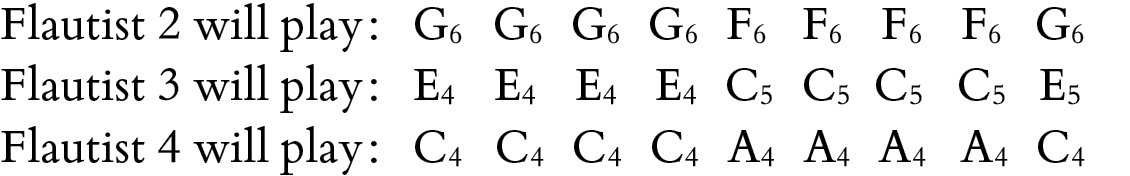

The other three flautists will play the accompanying harmony—each of them playing one note for each of the melody notes—and they will have a fairly boring time of it because their parts involve lots of repeating notes:

Now, you might think that the number of tune options our brain would have in this case would be very small. After all, the piece is only nine notes long.

But there are more melodies hidden in this simple piece of music than you could possibly imagine. This is because any sequence of notes can be a tune. In fact flautists 2, 3, and 4 are all playing their own tunes. Dull, repetitive tunes it’s true—but they are tunes.

So, how many hidden tunes are there?

The flautists as a group have a job to do. They have to deliver a sequence of nine groups of four notes to the listeners:

Group 1: C5, G6, E4, C4

Group 2: C5, G6, E4, C4

Group 3: G5, G6, E4, C4

Group 4: G5, G6, E4, C4

Group 5: A5, F6, C5, A4

Group 6: B5, F6, C5, A4

Group 7: C6, F6, C5, A4

Group 8: A5, F6, C5, A4

Group 9: G5, G6, E5, C4

In my original arrangement I happen to have given a certain selection of notes to flautist 1 and another selection to flautist 2. But if they swapped a few notes, the audience wouldn’t know the difference. In fact we could let all four flautists divvy up the notes from each group in whatever way they liked (before they started playing), and as long as all the notes were played in the correct sequence, the sound of the music wouldn’t change as far as the audience is concerned.

But when the flautists divide up the notes among them, they are choosing new tunes for themselves. And because our flautists have nine groups of notes, each with four choices, the actual number of possible tunes in our simple example is four multiplied by itself nine times: 4 x 4 x 4 x 4 x 4 x 4 x 4 x 4 x 4 = 262,144. Over a quarter of a million tunes* are hidden in just four seconds of music! If they tried all of these possibilities, our flautists would be swapping notes for several weeks before they got to the end of the project.

If we did this same exercise for the thirty-eight notes of the whole tune (with three notes of accompaniment for each note in the melody), the number of possible tunes would be over seventy-five thousand billion billion, which is more than the number of grains of sand on all the beaches on earth.

For a pop song, or any piece of harmonized music a few minutes long, the number of possible tunes would be more than the number of stars in the universe!

And these possible tunes are not something I’ve made up; they really are there. It’s just that we ignore the billions of possibilities and hear only one. Given the vast number of options, I think you’ll agree that our effortless ability to spot the “real” tune—the one the composer had in mind—is pretty amazing.

We achieve this phenomenal feat by using a collection of pattern recognition techniques that are part of our mental survival equipment. Our brain is continuously bombarded with vast amounts of data from our senses, and we simply wouldn’t live very long if we tried to analyze every detail. For this reason we have found it useful to group the things we see and hear into categories.1 Your average caveman didn’t stand around wondering if the unfamiliar spotted snake slithering toward him was as dangerous as the stripy one that killed his brother; he’d automatically put it in the “Snake! Run like hell!” category. Our categorization system groups things in several ways, and here are four of the main grouping methods, together with examples of how they are useful for survival:

Similarity. If things have features in common, we categorize them together. If we see an unfamiliar twenty-foot-tall plant with leaves and branches, we don’t need to worry about exactly what it is. We can simply categorize it as a tree. Having done so, we can assume that it will have tree-like qualities, which means that we can probably burn pieces of it to keep our fire going.

Proximity. If things are near one another, we categorize them together. You are using this skill at the moment to group letters into words as you read this sentence. If we find that a particular red currant bush down in the valley provides juicier berries than the bushes on the hillside, it’s likely that the other red currant bushes in the valley will also have high-quality fruit.

Good continuation. If several images look as if they are part of an incomplete group that makes up a bigger picture, your brain tends to join up the dots. This skill allows you to work out what you are looking at even if your view is obscured by something. This is what helps us to see a snake hiding in the branches of a tree.

Common fate. We have an ability to identify if several things are traveling in the same direction toward a certain end point. Watching a flock of birds in flight, we immediately notice if a few of them start to veer off in a slightly different direction. If this happens, we categorize them into two separate groups with different common fates. Common fate lets us identify which antelope is getting left behind by the herd, and in which direction the bees are buzzing back to their honey-filled hive.

These innate skills—like all innate skills—are part of our equipment for staying alive, and they allow us to sit down in a snake-free restaurant and pour red currant jus over our smoked venison fricassee.

OK—so what’s all this got to do with music?

Well, remarkably, our hearing system untangles the tune from the harmony by using the four skills I’ve just discussed.

Similarity. In many cases the instrument carrying the tune has a distinct sound or timbre. Often it’s a human voice, but in other cases it might be, for example, a saxophone or guitar. We link sounds with a similar timbre together, and this helps us follow the path of a tune. The accompanying instruments (e.g., keyboards or violins) have their distinctive timbres as well, which also helps us keep the harmony separate from the melody.

Proximity. There are two ways in which proximity helps us follow the melody. One is proximity in time: the notes of a melody follow one another in a sequence, with one note starting as the previous one ends (with occasional gaps). Because the notes are generally nose to tail like this, we can easily identify the individuals as being parts of a chain (the tune). Proximity in pitch is also an important clue that helps us identify the tune, because most of the time tunes use only small steps in pitch between consecutive notes.

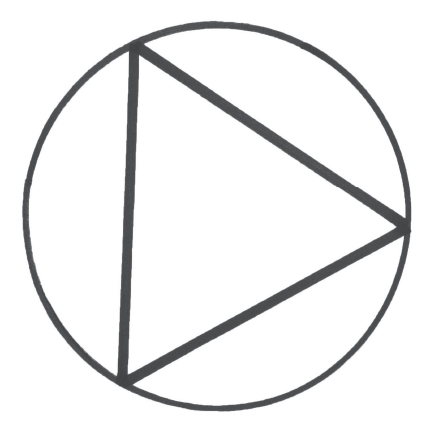

Good continuation. A tune is always on its way somewhere—up toward its highest note or down toward its lowest, with diversions along the way. In many cases we can guess what note will be next, and even when we can’t forecast the exact note, we can be pretty confident that certain notes are extremely unlikely. The way we keep track of the tune is impressive because in almost any music there will be accompanying notes that are timed to occur between the melody notes. To make a visual analogy here, the accompaniment will be interfering with our view of the melody. And the melody will be obscuring our view of the accompaniment. (The snake hides some of the branches and the branches hide some of the snake.) Our good continuation skills keep the melody separate by showing us that any particular accompanying note is very unlikely to be part of the melody and similarly that the next melody note probably isn’t part of the accompaniment. We use “good continuation” assumptions when listening to music in the same way that we separate out superimposed images on paper. For example, good continuation makes us interpret this image as a triangle within a circle—not as three capital D’s touching corner to corner.

Common fate. If the music we are listening to is being played by a group of similar instruments (a brass band or string orchestra, say) or by a solo instrument (a piano or a guitar), then the timbre of the melody will be the same as the timbre of the accompaniment. In this case one way to keep the tune separately identifiable is to pitch it much higher than the harmony. But eventually this will get boring and in many cases the tune will eventually descend back into the same range of notes as the harmony. You might think that we’d lose track of the tune in this situation, but fortunately this is where our ability to identify common fate comes in handy.

I mentioned earlier that the melody is always on its way somewhere—but the harmony also has its own agenda. The harmony is generally less dynamic and more obviously organized than the tune, and again, we can use a visual analogy here to show how we keep the tune and harmony separate. There is a cliché in action films whereby a couple of people who are chasing each other suddenly come across a parade of people marching down the street. At this point the person being chased disappears into the marching crowd and the chaser usually shinnies up a lamppost to look for him. Quite often the fugitive is spotted easily because he’s not traveling in exactly the same direction as the main crowd. The steady movement of the crowd makes it easy to identify the contrary motion of the individual. In this analogy the marching crowd is the harmony, the melody is the fugitive dodging through the crowd, and you are stuck halfway up a lamppost watching what’s going on.

Songwriters and composers automatically make use of the listener’s categorization skills because they are using their own when they write the music. In most cases the music consists of a tune and an accompaniment, and by now I hope you’re impressed with your brain’s ability to untangle one from the other. But there’s more… In many types of music there are occasions when more than one tune is playing at any one time. This technique, which is called polyphony, was particularly popular around 1700, and J. S. Bach was the master of the craft of having two or more tunes going at once, for several minutes at a time. Polyphony is also used, generally only for a few seconds at a time, in folk, pop, rock, and jazz music. For example, if you listen to the Beatles’ “Hello, Goodbye,” there is a section halfway through the song where two sets of lyrics are being sung, each with its own melody, at the same time. You can also hear Simon and Garfunkel using the same technique in their version of “Scarborough Fair.” In most modern music polyphony is used only sparingly, to add depth and interest to the sound. Under the main melody a short tune might be given to, say, the bass guitar, which will then pop out of the background for a little while before rejoining the accompaniment. An example of this can be found in the Rolling Stones’ version of “Route 66.” About forty-five seconds into the song, as Mick Jagger sings the few words that end with “pretty,” the bass plays a rising “melody” of four notes before returning to more standard accompaniment.

Our abilities to identify similarity, proximity, good continuation, and common fate work simultaneously to help us make sense of what we are hearing, even if there are several tunes going on at once. We also rely on our natural tendency to look for patterns we are already familiar with to help us follow the tune. Any Western music that you hear for the first time is full of little segments you’ve heard before in other pieces. For example, most tunes will contain fragments of scales, and lots of familiar intervals. Our mental library of these building blocks helps us make sense of new pieces fairly rapidly.

So listening to music requires a lot more mental juggling than you might have expected. Thankfully, all the information processing is subconscious and effectively effortless, so it doesn’t interfere with our enjoyment.