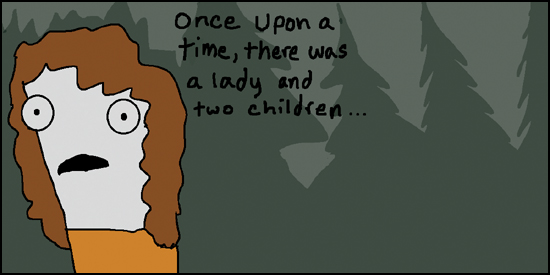

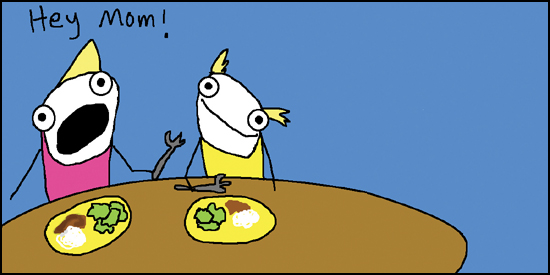

One morning, shortly after my family relocated to the mountains of northern Idaho, my sister and I woke up to find our mother lurking impatiently in our bedroom doorway. She was dressed like a woodsman.

Apparently, sometime during the night, she had awakened to the urgent realization that she lived near an area of wilderness, and, coincidentally, she had learned a few wilderness-related things from a short stint in the Girl Scouts, therefore she needed to take her children into the wilderness so that she could teach them the ways of the forest.

It was a noble goal.

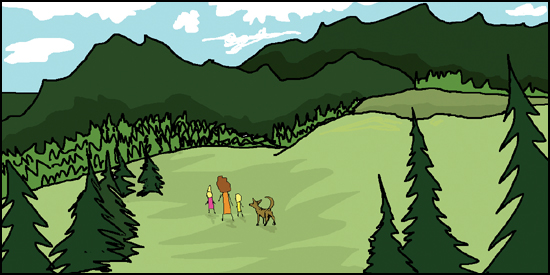

We set out shortly after sunrise on a path that twisted down a hill and eventually led to a fence, beyond which lay thousands of acres of wilderness. Our dog—a fat, disobedient Labrador mix named Murphy—trotted along next to us.

Once we crossed the fence, we had to cut our own trail through the underbrush, ducking under branches and stepping over fallen logs. Our mom tried to teach us things while we ran around like maniacs, kicking trees, throwing sticks at birds, and uprooting random plants simply because we were children and they were plants.

And Murphy, who had spent all day dragging huge logs around for no reason, was looking a little weary as well.

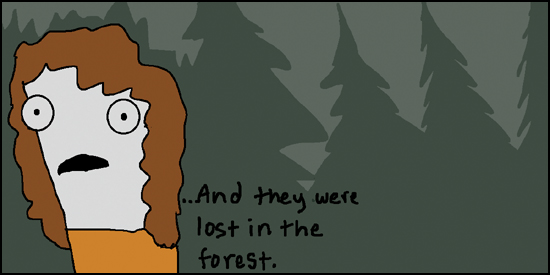

Our mother attempted to lead us back the way we came, but unfortunately, her natural sense of direction was no match for the sheer amount of directions there are, and she became disoriented.

She tried to be confident and follow her instincts, but after an hour of trudging through unfamiliar, waist-high plants, she accepted that she had no idea where she was going. She was lost in the forest with two young children and she was completely terrified.

She didn’t want to alarm us, so she tried to play it off like it was her choice to still be in the woods—like she was having so much fun that she couldn’t stand the idea of going home yet. But, you know, if she wanted to go home, she totally could.

When my sister asked where we were, our mother whirled around with a grin plastered across her face. “We’re in this little swampy area! Isn’t it fun?!” she said.

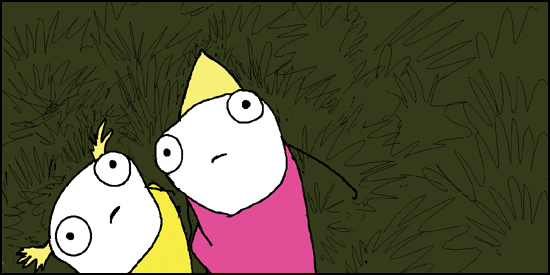

We weren’t able to muster the same amount of enthusiasm about the little swampy area.

She had to think fast if she wanted to maintain the illusion that we were still hanging out in the forest on purpose.

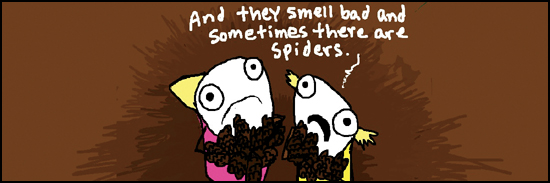

We didn’t want to find pine cones. We wanted to go home. But we didn’t really have a choice. Our leader wanted us to collect pine cones, so we obeyed, hoping that we could placate her as quickly as possible and move on.

We had severely underestimated how difficult the task was going to be.

We’d gather a bunch of pine cones, then trot over to our mother and ask her if we had found enough to be able to go home. “No. But maybe there are more on the other side of that hill,” she’d say. So we’d march over the hill to look for more. When we were on the other side of the hill, she’d say, “See where Murphy is on the far side of that meadow? I bet there are bigger pine cones over there. Let’s go find out!” Then she wanted browner pine cones. Then heavier pine cones.

Several hours later, we had come no closer to meeting our mother’s ludicrous standards. We were beginning to lose hope.

She was going to have to change her strategy.

We had spent hours combing the forest for the biggest, brownest, heaviest, cleanest pine cones it could offer, hoping that maybe, just maybe, if we found exactly the right ones, our mother would let us go home. We had bled for them. And now she was telling us that we had to abandon them.

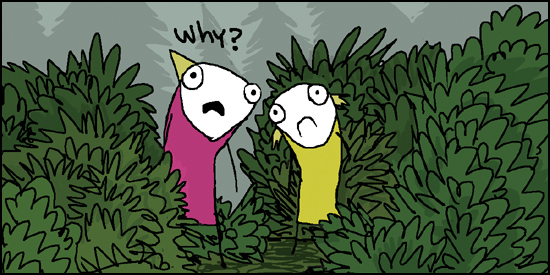

We were confused and more than a little demoralized, but we dutifully piled our pine cones near some bushes while our mom started playing “who can yell ‘help’ the loudest and the most” by herself.

It was a pretty anticlimactic game and we lost interest quickly.

We didn’t understand why she had suddenly become so intensely interested in playing these stupid games. Did she not realize it was getting dark?

“Please, Mom. Please, please, please let us go home. Please,” we pleaded. She just looked at us and said, “We haven’t even played ‘walk over that hill and see what’s on the other side’ yet.”

We tried to reason with her. “Mom, aren’t you hungry? And what about Dad? Don’t you miss Dad?”

Still, she refused to go home.

Our mother was clearly insane, so, as the eldest child, it fell upon me to step up and take charge of the situation. But without knowing how to find my way home, my options were pretty limited.

I silently assessed our predicament before deciding to implement the only real plan I could come up with. It was a risky plan—a plan that could easily backfire. But it was my only option.

I was going to have to scare my mother out of the forest.

Normally, I wouldn’t have been able to think of anything frightening enough to breach her grown-up resistance to scary kid stories. But a few nights earlier, she had watched The Texas Chainsaw Massacre while she thought I was asleep.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t asleep. I was hiding behind the couch.

And I had imprinted everything I’d seen that night.

I imagine it would be pretty terrifying to be wandering through the forest at night when, out of nowhere, your eight-year-old child begins describing the plot from the horror film you watched the other night, which, as far as you know, she hadn’t seen. But my mother maintained her composure very well—until a twig snapped, at which point she whirled around shrieking, “WE HAVE A DOG!” As if Murphy’s presence were enough to deter a homicidal psychopath with a chainsaw.

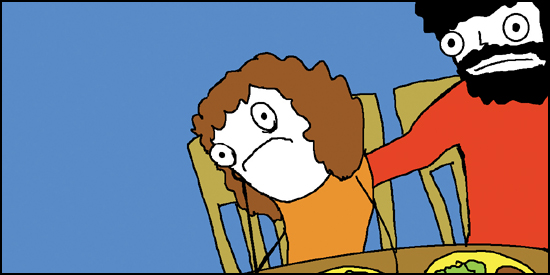

It was too much. All the helplessness and frustration that she had been trying so hard to hide from us came rushing to the surface.

She couldn’t keep up the illusion forever. At some point we were going to figure out that the last seven hours of our adventure had not been on purpose. And then we were going to panic as we realized that—contrary to our prior assumptions—we did not have the option of going home.

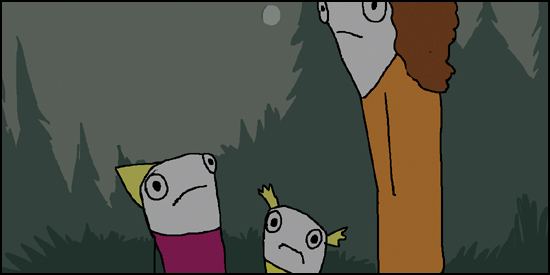

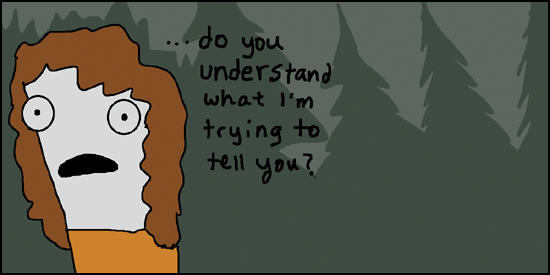

She pulled herself together and broke the news as gently as possible.

It must have been difficult for her to watch our innocent, hopeful little faces go blank in confusion, and then slowly contort in horror as our sense of security shattered.

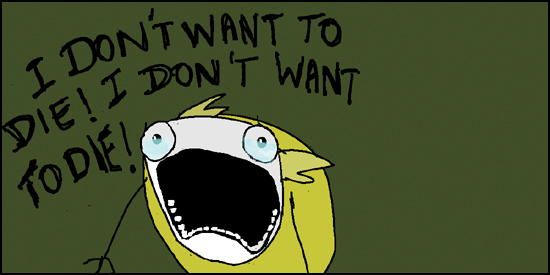

And it must have been especially horrible when my sister panicked and started scream-crying uncontrollably.

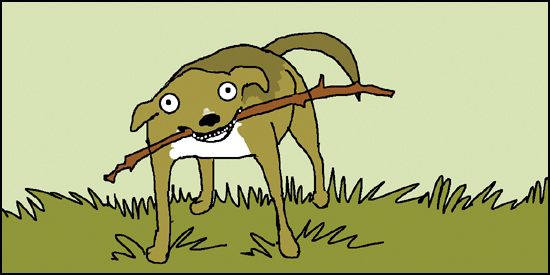

Sensing that there was something amiss, Murphy picked up the largest stick she could find and ran loops around the meadow.

Our mother stared at Murphy in silence for a long time. Finally, she spoke.

“Maybe Murphy knows the way.” She reasoned that, because Murphy was a dog, she would have an innate homing instinct.

She spoke to Murphy in a slow, deliberate voice. “Murphy . . . home? Murphy go home? Home? Home, Murphy. Hoooome.”

We waited for Murphy to seize the heroic opportunity that was upon her.

But Murphy wasn’t like the dogs you see in movies like Homeward Bound. Her chief concern seemed to be treating sticks as violently as possible.

However, she was our only hope.

Murphy’s actions over the next few hours didn’t seem particularly purposeful. But at some point during one of her stick-thrashing sprees, she took off into the woods—presumably to see what it would feel like to run into a lot of objects while holding a small tree trunk in her mouth—and her path of travel happened to intersect with an old logging road. We followed the logging road to a clearing, and on a hill in the distance we could see a house with its lights on.

The house belonged to an elderly couple who were quite alarmed when our mother banged on their front door so late at night, but kindly offered to let her use their phone to call our dad.

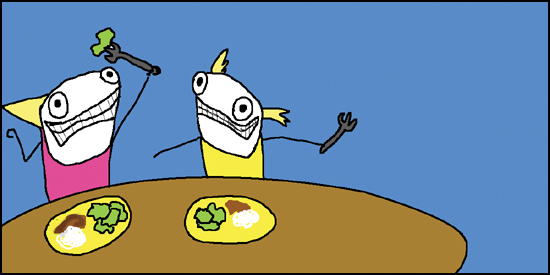

And finally, we got to go home.

We never did go back for the pine cones.