In Fields Near Home

Any autumn. Every autumn, so long as my luck holds and my health, and if I win the race. The race is a long, slow one that has been going on since I started to hunt again. The race is between my real competence at hunting gradually developing, and, gradually fading, the force of the fantasies which have sustained me while the skills are still weak. If the fantasies fade before the competence is really mine, I am lost as a hunter because I cannot enjoy disgust. I will have to stop, after all, and look for something else.

So I shan’t write of any autumn, or every autumn, but of last autumn, the most recent and the most skilled. And not of any day, but a particular day, when things went really well.

7:45 No clock need wake me.

7:55 While I am pulling on my socks, taking simple-minded satisfaction in how clean my feet are from last night’s bath, relishing the feel against them of heavy, close-knit wool, fluffed and warmed and freshly washed, the phone rings downstairs. I go down to answer it, stocking-footed and springy-soled, but I am not wondering particularly who the caller is. I am still thinking about clean feet and socks. Even 20 years after infantry training, I can remember what it is like to walk too far with wet lint, cold dirt, and calluses between the flesh and the matted stocking sole, and what it is like to long for the sight of one’s own unfamiliar feet and for the opportunity to make them comfortable and unrepulsive.

It is Mr. Burton on the phone.

“Hello?”

“Yeah. Hi, Mr. Burton.”

“Say, I’ve got some news. I called a farmer friend of mine, up north of Waterloo last night. He says there’re lots of birds, his place hasn’t been hunted for a week.”

“Uh-huh.”

“I thought we’d go up there instead.”

Mr. Burton is a man in his late 50s whom I’ve known for two or three years. He took me duck hunting once, to a privately leased place, where we did quite well. I took him pheasant hunting in return, and he has a great admiration for my dog Moon. He wants his nephew to see Moon work. The kid has a day off from school today.

But: “The boy can’t go after all,” Mr. Burton says. “His mother won’t let him. But say, I thought we might pick up Cary Johnson—you know him don’t you? The attorney. He wants to go. We’ll use his car.”

Boy, I can see it. It’s what my wife calls the drive-around. Mr. Burton will drive to my house; he will have coffee. We will drive to Johnson’s house. We will have coffee while Johnson changes to different boots—it’s colder than he expected. Johnson will meet a friend who doesn’t want to hold us fellows up, but sure would like to go if we’re sure there’s room. We will have coffee at the drugstore while Johnson’s friend goes home, to check with his wife and change. It will be very hot in the drugstore in hunting clothes; the friend will phone and say he can’t go after all. Now nothing will be holding us up but the decision to change back to my car, because Johnson’s afraid my dog’s toenails will rip his seat covers. Off for Waterloo, two hours away (only an hour and a half if Mr. Burton knew exactly how to find the farm). The farmer will have given us up and gone to town. Now that we’re here, though, we will drive into town to the feed store, and . . .

“Hell, Mr. Burton,” I say. “I’m afraid I can’t go along.”

“Sure you can. We have a date, don’t we?”

“I’ll be glad . . .”

“Look, I know you’ll like Johnson. That’s real hunting up there—I’ll bet you five right now we all get limits.”

I will not allow myself to think up an excuse. “I’m sorry,” I say. “I’ll be glad to take you out around here.” I even emphasize you a little to exclude Johnson, whoever he is.

“I pretty much promised my farmer friend . . . Oh, look now, is it a matter of having to be back or something?”

“I’m sorry.”

“Well, I told him we’d come to Waterloo. There are some things I have to take up to him.”

Not being among the things Mr. Burton has to take to his farmer friend, nor my dog either, I continue to decline. Hot damn. Boy, boy, boy. A day to myself.

Ten months a year I’m a social coward, but it’s hard to bully me in hunting season, especially with clean socks on.

8:05 Shaving: unnecessary. Shaving for fun, with a brand new blade. Thinking: Mr. Burton, sir, if your hunting is good, and you

| get a limit of three birds, in two hours | 2 |

| & it takes two hours’ driving to get there | 2 |

| & an hour of messing around on arrival | 1 |

| & an hour for lunch | 1 |

| & two hours to get back and run people home | 2 |

| 8 |

you will call it a good hunt, though the likelihood is, since you are no better shot than I, that other men will have shot one or more of your three birds. There is a shootas-shoot-can aspect to group hunts; it’s assumed that all limits are combined, and it would be considered quit boorish to suggest that one would somehow like to shoot one’s own birds.

Thinking: suppose I spend the same eight hours hunting, and it takes me all that time to get three pheasants. In my eccentric mind, that would be four times as good a hunt, since I would be outdoors four times as long. And be spared all that goddamn conversation.

Chortling at the face behind the lather: pleasant fellow, aren’t you?

Thinking: God I like to hunt near home. The known covert, the familiar trail. And in my own way and at my own pace, considering any other man’s. Someday I’ll own the fields behind my house, and there’ll be nothing but a door between me and the game—pick up a gun, call a dog, slip out. They’ll know where I’ve gone.

Thinking as I see the naked face, with no lather to hide behind now: I’ll take Mr. Burton soon. Pretty nice man. I’ll find him birds, too, and stand aside while he shoots, as I did for Jake, and Grannum, and that short guy, whatever his name was, looked so good. Moon and I raised three birds for him, one after another, all in nice range, before he hit one. Damn. That’s all right. I don’t mind taking people. It’s a privilege to go out with a wise hunter; a pleasure to go out with one of equal skill, if he’s a friend; and a happy enough responsibility to take an inexperienced one sometimes. Eight or 10 pheasants given away like that this season? Why not? I’ve got 12 already myself, more than in any season before and this one’s barely 10 days old. And for the first time, missed fewer than I’ve hit.

Eggs?

8:15 Sure! Eggs! Three of them! Fried in that olive oil, so they puff up. With lemon juice. Tabasco. Good. Peppery country sausage, and a stack of toast. Yes, hungry. Moon comes in.

“Hey, boy. Care to go?”

Wags.

“Wouldn’t you just rather stay home today and rest up?”

Wags, grins.

“Yeah, wag. If you knew what I said you’d bite me.”

Wags, stretches, rubs against me.

“You’d better have some breakfast, too.” I go to the refrigerator. Moon is a big dog, a Weimaraner, and he gets a pound of hamburger mornings when he’s going to be working. I scoop out cold ground meat from its paper carton, and pat it between my hands into a ball. I roll it across the floor, under his dignified nose. This is a silly game we play; he follows it with his eyes, then pounces as if it really were a ball, trapping it with a paw. My wife, coming in from the yard, catches us.

“Having a game of ball,” I say.

“What is it you’re always telling the children about not making the same joke twice?”

“Moon thinks it’s funny.”

“Moon’s a very patient dog. I see you’re planning to work again today.”

I smile. I know this lady. “I really should write letters,” I say.

“They can wait, can’t they?” She smiles. She likes me to go hunting. She’s still not really convinced that I enjoy it—when we were first married I liked cities—but if I do enjoy it, then certainly I must go.

Yes, letters can wait. Let them ripen a few more days. It’s autumn. Maybe some of them will perish in the frost if I leave them another week or two—hell, even the oldest ones are barely a month old.

8:45 I never have to tell Moon to get in the car. He’s on his hind legs, with his paws on the window, before I reach it. As I get in, start the car, and warm it up, an image comes into my mind of a certain hayfield. It’s nice the way this happens; no reasoning, no weighing of one place to start against another. As if the image were projected directly by the precise feel of a certain temperature, a certain wind strength—from sensation to picture without intervening thought. As we drive, I can see just how much the hay should be waving in the wind, just how the shorter grass along the highway will look, going from white to wet as the frost melts off—for suddenly the sun’s quite bright.

8:55 I stop, and look at the hayfield, and if sensation projected an image of it into my mind, now it’s as if my mind could project this same image, expanded, onto a landscape. The hay is waving, just that much. The frost is starting to melt.

“Whoa, Moon. Stay.”

I have three more minutes to think it over. Pheasant hunting starts at nine.

“Moonie. Quiet, boy.”

He is quivering, whining, throwing his weight against the door.

I think they’ll be in the hay itself—tall grass, really, not a seeded crop; anyway, not in this shorter stuff that grows in the first 100 yards or so along the road. Right?

8:58 Well. Yeah. Whoa.

The season’s made its turn at last. Heavy frost every morning now. No more mosquitoes, flies. Cold enough so that it feels good to move, not so cold that I’ll need gloves: perfect. No more grasshoppers, either. A sacrifice, in a way—pheasants that feed on hoppers, in open fields, are wilder and taste better than the ones that hang around corn.

The season’s made its turn in another sense—the long progression of openings is over: Rabbits, squirrels, September 15. Geese, October 5. Ducks, snipe, October 27. Quail, November 3. Pheasants, November 10. That was 10 days ago. Finally, everything that’s ever legal may be hunted. The closings haven’t started yet. Amplitude. Best time of the year. Whoa.

8:59: Whoa! Now it’s me quivering, whining, but I needn’t throw my weight against the door—open it. I step out, making Moon stay. I uncase the gun, look at it with love, throw the case in the car; load. Breathe cold air. Good. Look around. Fine.

“Come on, Moonie. Nine o’clock.”

9:00 I start on the most direct line through the short grass, toward the tall, not paying much attention to Moon, who must relieve himself. I think this is as much a matter of nervous tension as it is of regularity.

“Come on, Moon,” I call, keeping to my line. “This way, boy.”

He thinks he’s got a scent back here, in the short grass; barely enough for a pheasant to hide in, and much too thin for cold-day cover.

“Come, Moon. Hyeahp.”

It must be an old scent. But he disregards me. His stub of a tail begins to go as he angles off, about 30 yards from where I am; his body lowers just a little and he’s moving quickly. I am ignorant in many things about hunting, but there’s one thing I know after eight years with this dog, if you bother to hunt with a dog at all, believe what he tells you. Go where he says the bird is, not where you think it ought to be.

I move that way, going pretty quickly myself, still convinced it’s an old foot-trail he’s following, and he stops in a half-point, his head sinking down while his nose stays up, so that the gray neck is almost in a shallow S-curve.

A cock, going straight up, high, high, high. My gun goes up with him and is firm against my shoulder as he reaches the top of his leap. He seems to hang there as I fire, and he drops perfectly, two or three yards from where Moon waits.

“Good dog. Good boy, Moon,” I say as he picks the heavy bird up in his mouth and brings it to me. “Moonie, that was perfect.” The bird is thoroughly dead, but I open my pocket knife, press the blade into the roof of its mouth so that it will bleed properly. Check the spurs—they’re stubby and almost rounded at the tip. This year’s pheasant, probably. Young. Tender. Simply perfect.

Like a book pheasant, I think, and how seldom it happens. In the books, pheasants are said to rise straight up as this one did, going for altitude first, then pausing in the air to swing downwind. The books are quite wrong; most pheasants I see take straight off, without a jump, low and skimming, curving if they rise much, and never hanging at all. I wonder about evolution: among pheasant generations in this open country, did the ones who went towering into the air and hung like kites get killed off disproportionately? While the skulkers and skimmers and curvers survived, to transmit crafty genes?

“Old-fashioned pheasant, are you? You just set a record for me. I never dreamed I’d have a bird so early in the day.” I check my watch.

9:15 The device I was so hopeful of is not working out too well. It is a leather holder that slides onto the belt, and has a set of rawhide loops. As I was supposed to, I have hooked the pheasant’s legs into a loop, but he swings against my own leg at the knee. Maybe the thing was meant for taller men.

“Moon. This way. Come around, boy.” I feel pretty strongly that we should hunt the edge.

The dangling bird is brushing grass tops. Maybe next time I should bring my trout creel, which is oversized, having been made by optimistic Italians. No half-dozen trout would much more than cover the bottom, but three cock pheasants might he nicely in the willow, their tails extending backwards through the crack between lid and body, the rigidity of the thing protecting them as a game bag doesn’t.

“Moon. Come back here. Come around.” He hasn’t settled down for the day. Old as he is, he still takes a wild run, first thing.

I’m pretty well settled, myself (it’s that bird bumping against my leg). Now Moon does come back into the area I want him in, the edge between high grass and low; there’s a distinction between following your dog when he’s got something and trusting him to weigh odds. I know odds better, and here is one of those things that will be a cliché of hunting in a few years since the game-management men are telling it to one another now and it’s started filtering into outdoor magazines: the odds are that most game will be near the edge of cover, not in the center of it. The phrase for this is “edge factor.”

“Haven’t you heard of the edge factor?” I yell at Moon. “Get out along the edge here, boy.” And in a few steps he has a scent again. When he’s got the tail factor going, the odds change, and I follow him, almost trotting to keep up, as he works from edge to center, back toward edge, after what must be a running bird. He slows a little, but doesn’t stops; the scent is hot, but apparently the bird is still moving. Moon stops, points, holds. I walk as fast as I can, am in range—and Moon starts again. He is in a crouch now, creeping forward in his point. The unseen bird must be shifting: he is starting to run again, for Moon moves out of the point and stars to lope: I move, fast as I can and still stay collected enough to shoot—gun held in both hands out in front of me—exhilarated to see the wonderful mixture of exuberance and certainty with which Moon goes. To make such big happy moves, and none of them a false one, is something only the most extraordinary human athletes can do after years of tanning it comes naturally to almost any dog. And that pheasant there in front of us—how he can go! Turn and twist through the tangle of steam stems, never showing himself, moving away from Moon’s speed and my calculations. But we’ve got him—I think we do—Moon slows, points. Sometimes we win in a run down usually not usually the pheasant picks the right time, well out and away, to flush out of range—but this one stopped. Yes. Moon’s holding again. I’m in range. I move up, beside the rigid dog. Past him. WHIRR-PT. The gun rises, checks itself, and I yell at Moon, who is ready to bound forward:

“Hen!”

Away she goes, and away goes Moon, and I yell: “Whoa. Hen, hen,” but it doesn’t stop him. He’s pursuing, as if he could get up enough speed to rise onto the air after her. “Whoa.” It doesn’t stop him. WHIRRUPFT. That stops him. Stops me too. A second hen. WHIRRUPFT. WHIRRUPFT. Two more. And another, that makes five who were sitting tight. And then, way out, far from this little group, through which he must have passed, and far from us, I see the cock—almost certainly the bird we were chasing (hens don’t run like that)—fly up silently, without a cackle, and glide away, across the road and out of sight.

9:30 “There’s got to be another,” I say to Moon. A man I know informed me quite vehemently a week ago that one ought never to talk to a dog in the field except to give commands; distracts him, the man said, keeps him too close. Tell you what, man: you run your dogs your way, and I’ll run my dog mine. Okay?

We approach a fence, where the hayfield ends; the ground is clear for 20 feet before the fence line. Critical place. If birds have been moving ahead of us, and are reluctant to fly, this is where they’ll hide. They won’t run into the open. And just as I put this card in the calculator, one goes up. CUK CUK CUK, bursting past Moon full speed and low, putting the dog between me and him so that, while my gun is ready, I can’t shoot immediately; he rises only enough to clear the fence, sweeping left between two bushes as I fire, and I see the pellets agitate the leaves of the right-hand bush, and I know I shot behind him.

Moon, in the immemorial way of bird dogs, looks back to me with what bird hunters who miss have immemorially taken for reproach.

We turn along the edge paralleling the fence. He may not have been the only one we chased down here—Moon is hunting, working from fence to edge, very deliberate. Me too. I wouldn’t like to miss again. Moon swerves to the fence row, tries some likely brush. Nope. Lopes back to the edge, lopes along it. Point. Very stiff. Very sudden. Ten yards, straight ahead.

This is a beautifully awkward point, Moon’s body curved into it, shoulders down, rear up, head almost looking back at me; this one really caught him. As now we’ll catch the pheasant? So close. Dog so steady. I have the impression Moon’s looking a bird straight in the eye. I move slowly. No need for speed, no reason to risk being off balance. Let’s be so deliberate, so cool, so easy. The gun is ready to come up—I never have the feeling that I myself bring it up. Don’t be off balance. He’ll go now. Now. Nope—when he does, I try to tell myself, don’t shoot too fast, let the bird get out a little, but I’m not really that good and confident in my shooting. Thanks be for brush loads. Ought to have them in both barrels for this situation. Will I have to kick the pheasant out? I am within two steps of Moon, who hasn’t stirred except for the twitching of his shoulder and haunch muscles, when the creature bolts. Out he comes, under Moon’s nose, and virtually between my legs if I didn’t jump aside—a rabbit, tearing for the fence row. I could recover and shoot, it’s an easy shot, but not today; I smile, relax, and sweat flows. I am not that desperate for game yet.

I yell “Whoa” at Moon, and for some dog’s reason he obeys this time. I should punish him, now; for pointing fur? But it’s my fault—sometimes, being a one-dog man, I shoot fur over him, though I recognize it as a genuine error in bird-dog handling. But with the long bond of hunting and mutual training between us (for Moon trained me no less than I did him), my taking a rabbit over him from time to time—or a mongoose, or a kangaroo—is not going to change things between us.

In any case, my wife’s never especially pleased to see me bring a rabbit home, though the kids and I like to eat them. I pat Moon, who whoaed for the rabbit. “Whoa, big babe,” I say softly. “Whoasie-posner, whoa-daboodle-dog, big sweet posner baby dog . . .” I am rubbing his back.

10:40 Step out of the car, look around, work it out: the birds slept late this morning, because of the wind and frost, and may therefore be feeding late. If so, they’re in the field itself, which lies beyond two fallow fields. They roost here in this heavy cover, fly out to the corn—early on nice mornings; later, if I’m correct, on a day like this. When they’re done feeding, they go to what game experts call loafing cover—relatively thin cover, near the feeding place, and stay in it till the second feeding in the afternoon; after which they’ll be back here where they started, to roost again.

The wind is on my left cheek, as Moon and I go through the roosting cover, so I angle right. This will bring us to where we can turn and cross the popcorn field, walking straight into the wind. This will not only be better for Moon, for obvious reasons, but will also be better for shooting; birds in open rows, hearing us coming, can sail away out of range very fast with the wind behind them. If it blows towards me, they’ll either be lifted high, going into the wind, or curve off to one side or the other.

The ragweed, as we come up close to it and Moon pauses before choosing a spot at which to plunge in, is eight feet high—thick, dry, brittle, gray-stemmed stuff that pops and crackles as he breaks into it. I move a few feet along the edge of the draw, shifting my position as I hear him working through, to stay as well in range of where he is as possible. I am calmly certain there’s a bird in there, even that it’s a cock. I think he moved in ahead of us as we were coming up the field, felt safe when he saw us apparently about to pass by, and doesn’t want to leave the defense overhead protection now.

But he must. Moon will send him up in a moment, perhaps out the far side where the range will be extreme. It will be a long shot, if that happens, and Moon is now at the far edge, is turning along it, when I hear the cackle of the cock rising. For a moment I don’t know where, can’t see him, and by the time I do he’s going out to my right, almost back towards me, having doubled away from the dog. Out he comes, already in full flight and low, with the wind behind him for speed. And yet I was so well set for this, for anything, that it all seems easy—to pivot, mounting the gun as I do, find it against my cheek and the bird big and solid at the end of the barrel, swing, taking my time, and shoot. The bird checks, fights air, and tumbles, and in my sense of perfection I make an error: I am so sure he’s perfectly hit that I do not take the second shot, before he falls in some waist-high weeds. I mark the place by keeping my eye on a particular weed, a little taller than the others, and walk slowly, straight towards it, not letting my eye move away, confident he’ll be lying right by it. Moon, working the ragweed, would neither see the rise nor mark the fall and he comes bounding out to me now, coming to the sound of the shot. I reach the spot first, so very carefully marked, and there’s no bird there.

Hunters make errors; dogs correct them. While I am still standing there, irritated with myself for not having shot twice, Moon is circling me, casting, inhaling those great snuffs, finding the ground scent. He begins to work a straight line, checks as I follow him, starts again in a slightly different direction; I must trust him, absolutely, and I do. I remind myself that once he trailed a crippled bird more than half a mile in the direction opposite from that in which I had actually seen the bird start off. I kept trying to get him to go the other way, but he wouldn’t; and he found the pheasant. It was by the edge of a dirt road, so that Max Morgan and I could clock the distance afterwards by car speedometer.

Our present bird is no such problem. Forty feet from where the empty shell waves gently back and forth on top of the weed, Moon hesitates, points. Then, and I do not know how he knows that this particular immobile pheasant will not fly (unless it’s the smell of fresh blood), Moon lunges. His head darts into matted weeds, fights spurs for a moment, tosses the big bird once so that he can take it by the back, lifts it; and he comes to me proudly, trotting, head as high as he can hold it.

11:00 Iowa hunters are obsessed with corn. If there are no birds in the cornfields, they consider the situation hopeless. This may come from the fact that most of them hunt in drives—a number of men spread out in line, going along abreast through standing corn, with others blocking the end of the field. My experience, for I avoid that kind of hunt every chance I get, is quite different; I rarely find pheasants in cornfields, except along the edges. More than half of those I shoot. I find away from corn, in wild cover, and sometimes the crops show that the bird has not been eating grain at all but getting along on wilder seeds.

But as I start to hunt the popcorn field, something happens that shows why driving often works out. We start into the wind, as planned, moving down the field the long way, and way down at the other end a farm dog sees us. He starts towards us, intending to investigate Moon, I suppose. I see him come towards the field; I see him enter it, trotting our way, and the wind carries the sound of his barking. And then I see—the length of a football field away, reacting to the farm dog—pheasants go up; not two or three, but a flock, 12 or 14, and another and another and another, cocks and hens, flying off in all directions, sailing down wind and out of sight. Drivers and blockers would have had fast shooting with that bunch—but suppose I’d got up? Well, this gun only shoots twice. And, well again, boy. Three’s the limit, dunghead. And you’ve got two already.

11:30 Two birds before lunch? I ought to limit out, I ought to limit out soon. And stop looking for pheasants, spend the afternoon on something else. Take Moon home to rest, maybe, and know that the wind’s going down and the sun’s getting hot, go into the woods for squirrels, something I like but never get around to.

Let ’s get the other one. Where?

We are walking back to the car, the shortest way, no reason to go through the popcorn field after what happened. Where? And I think of a pretty place, not far away.

11:45 Yes, it’s pretty. Got a bird here last year, missed a couple, too, why haven’t I been here this season? It’s a puzzle, and the solution, as I step the car once more, is a pleasure: I know a lot of pretty places near home, 20 or 30 of them, all quite distinct, and have gotten or missed birds at all of them, one season or another.

There are no pheasants this time, only signs of pheasant: roosting places, full of droppings. Some fresh enough so that they were dropped this morning. A place for the next windy morning: I put that idea in a safe place and move back, after Moon—he’s pretty excited with all the bird scent, but not violently; it’s not that fresh—towards the fence along the soybean field. We turn from the creek, and go along the fence line, 20 or 30 feet out, towards an eight-acre patch of woods where I have often seen deer, and if I were a real reasoner or a real instinct man, not something in between, what happens would not find me unprepared. Moon goes into a majestically rigid point, foreleg raised, tail out straight, aimed at low bushes in the fence row. I hardly ever see him point so rigidly without first showing the signs he gives while the quarry is still shifting. I move in rather casually, suspecting a hen, but if it ’s a cock rather confident, after my last great shot, and there suddenly comes at me, buzzing angrily, a swarm of—pheasants? Too small—hornets? Sparrow? Quail! Drilling right at me, the air full of them, whirring, swerving to both sides.

Much too late, surprised, confused—abashed, for this is classic quail cover—I flounder around, face back the way I came, and pop off a pair of harmless shots, more in valediction than in hope of hitting. Turn back to look at Moon, and up comes a straggler, whirring all by himself, also past me. There are no easy shots on quail, but I could have him, I think, if both barrels weren’t empty. He’s so close that I can see the white on neck and face, and know him for a male. Jock though I am, at least I mark him down, relieved that he doesn’t cross the creek.

Moon works straight to the spot where I marked the straggler, and sure enough he flushes, not giving the dog a chance to point, flushes high and I snap-shoot and he falls. Moon bounds after him and stops on the way, almost pitching forward, like a car when its brakes lock. Another bird. Ready. I hope I have my down bird marked. Careful. Whirr—I damn near stepped on him, and back he goes behind me. I swing 180 degrees, and as he angles away have him over the end of the barrel. As I fire, it seems almost accidental that I should be on him so readily, but it’s not of course—it’s the one kind of shot that never misses, the unplanned, reflexive shot, when conditioning has already operated before self-consciousness could start up. This quail falls in the soft maple seedlings, in a place I won’t forget, but the first one may be hard.

He’s not. I find him without difficulty, seeing him on the ground at just about the same time that Moon finds him too. Happy to have him, I bring Moon back to the soft maple seedlings, but we do not find the second bird.

12:30 Lunch is black coffee in the thermos, an apple and an orange, and the sight of two quail and two pheasants, lying in a neat row on the car floor. I had planned to go home for lunch; and it wouldn’t take so very much time; but I would talk with my family, of course, and whatever it is this noon that they’re concerned with, I would be concerned with. And that would break the spell, as an apple and an orange will not.

12:45 Also

1:45 and, I’m afraid

2:45 these hours repeat one another, and at the end of them I have: two pheasants, as before: two quail; and an afterthought.

The afterthought shouldn’t have run through my mind, in the irritable state that it was in.

The only shots I took were at domestic pigeons, going by fast and far up, considered a nuisance around here; I missed both times. But what made me irritable were all the mourning doves.

There are doves all over the place in Iowa, in every covert that I hunt—according to the last Audubon Society spring census at Des Moines, doves were more common even than robins and meadow larks. In my three hard hours of barren pheasant hunting, I could have had shots at 20 or 25 doves (a game bird in 30 states, a game bird throughout the history of the world), and may not try them. Shooting doves is against the law in Iowa. The harvesting of our enormous surplus (for nine out of 10 will die before they’re a year old anyway) is left to cats and owls and—because the dove ranges get so crowded—germs.

Leaving the half-picked cornfield, I jump yet another pair of doves, throw up my gun and track them making a pretended double, though I doubt that it would work.

Three hours of seeing doves, and no pheasants, has made me pettish, and perhaps I am beginning to tire.

A rabbit jumps out behind the dog, unseen by Moon but not by me. At first I assume that I want to let him go, as I did the earlier one; then he becomes the afterthought: company, dinner—so you won’t let me shoot doves, eh, rabbit? He’s dead before he can reach cover.

3:00 Now I have only an hour left to get my final bird, for pheasant hunting ends at four. This is a symbolic bird: a good hunter gets his limit. At noon it seemed almost sure I would; suddenly it’s doubtful.

I sit in the car, one hand on Moon who is lying on the seat beside me. We’ve reached the time of the day when he rests when he can.

3:10 On my way to someplace else, I suddenly brake the car.

“Hey, did you see that?” I am talking to Moon again. He has a paw over his nose, and of course saw nothing. I look over him, eagerly, out the window and down into a big marsh we were about to pass by. We were on our way to the place I’d thought of, an old windbreak of evergreens near an abandoned farmhouse site, surrounded by overgrown pasture, and not too far from corn—It’s an ace in-the-hole kind of place for evening shooting, for the pheasants come in there early to roost; I’ve used it sparingly, shown it to no one.

Going there would be our best chance to fill out, I think, but look: “Damn, Moon, snipe. Snipe, boy, I’m sure of it.”

On the big marsh, shore birds are rising up and setting down, not in little squadrons like killdeer—which are shore birds about the same size, and very common—but a bird here, a bird there. Becoming instantly invisible when they land, too, and so not among the wading shore birds. I get out the glasses and step out of the car, telling Moon to stay. I catch one of the birds in the lenses, and the silhouette is unmistakable—the long, comic beak, the swept-back wings.

“You are snipe,” I say, addressing—well, them, I suppose. “Where’ve you boys been?”

Two more whiz in and out of the image, too quickly to follow, two more of my favorite of all game birds. Habitat changes around here so much from year to year, with the great fluctuations in water level from the dam, that this marsh, which was full of snipe three years ago, has shown none at all so far this year. What snipe hunting I’ve found has been in temporarily puddled fields, after rains, and in a smaller marsh.

“I thought you’d never come,” I say. “Moon!” I open the car door. “Moon, let’s go.” My heartiness is a little false, for snipe are my favorite bird, not Moon’s. He’ll flush them, if he must, but apparently they’re distasteful to him, and when I manage to shoot one, he generally refuses even to pick it up, much less retrieve it for me.

Manage to shoot one? Last year, on the first day I hunted snipe, I shot 16 shells before I hit my first. That third pheasant can wait there in the hole with the other aces.

Remembering the 16 straight misses, I stuff my pockets with shells—brush loads still for the first shot but, with splendid consistency, high-brass 7½s for the second, fullchoke shot. I won’t use them on a big bird, like a pheasant; I will on a tiny bird, like a snipe. The snipe goes fast, and by the second shot you need all the range you can get.

I should have hip boots now. Go back and get them? Nuts. Get muddy.

Down we go, Moon with a certain silly enthusiasm for the muskrats he smells and may suppose are now to be our quarry. I see that the marsh water is shallow, but the mud under it is always deep—thigh-deep in some places; the only way to go into it is from hummock to hummock of marsh grass. Actually, I will stay out of it if I can, and so I turn along the edge, Moon hunting out in front. A snipe rises over the marsh at my right, too far to shoot at, scolding us anyway: scaip, scaip. Then two more, which let the dog get by them, going up between me and Moon—a chance for a double, in a highly theoretical way, I shoot and miss at the one on the left as he twists low along the edge. He rises, just after the shot, going up in a tight turn, and I shoot again, swinging up with him, and miss again.

At my first shot, the other snipe—the one I didn’t shoot at—dove, as if hit. But I know he wasn’t; I’ve seen the trick before. I know about where he went in, and I decide not to bother with Moon, who is chasing around in the mud, trying to convince himself that I knocked down a pheasant or something decent like that.

I wade in myself, mud to ankles, mud to calves, up to the tops of the low boots I’m wearing; no bird? What the hell, mud over the boot tops, and I finally climb a hummock. This puts up my diving snipe, 10 yards further out and scolding, but the hummocks are spaced too far apart in this part of the swamp so there’s no point shooting. I couldn’t recover him and I doubt that Moon would. I let him rise, twist, swoop upwards, and I stand as still as I can balanced on the little mound of grass; I know a trick myself. It works; at the top of his climb the snipe turns and comes streaking back, 40 yards up, directly overhead. I throw up the gun for the fast overhead shot, and miss.

I splash back to the edge and muck along. A snipe goes up, almost at my feet, and his first swerve coincides with my snap shot—a kind of luck that almost seems like skill. Moon, bounding back, has seen the bird fall and runs to it—smells it, curls his lip and slinks away. He turns his head to watch me bend to pick it up, and as I do, leaps back and tries to take it from me.

“Moondog.” I say, addressing him severely by his full name. “I’m not your child to punish. I like this bird. Now stop it.”

We start along again, come to the corner where the marsh dies out, and turn. Moon stops, sight-pointing in a half-hearted way, and a snipe goes up in front of him. This one curves towards some high weeds: I tire and miss, but stay on him as he suddenly straightens and goes winging straight out, rising very little. He is a good 40 yards away by now, but he tumbles when I fire, and falls on open ground. It takes very little to kill a snipe. I pace the distance, going to him, and watch Moon, for Moon picks this one up. Then, when I call to him to bring it, he gradually, perhaps sulkily, lowers his head and spits it out again. He strolls off as if there were nothing there. I scold him as I come up, but not very hard: he looks abashed, and makes a small show of hunting dead in a bare spot about 10 yards from where we both know the snipe is lying I pick up the bird, and tell Moon that he is probably the worst dog that ever lived, but not in an unkind voice for I wouldn’t want to hurt his feelings.

This a pleasanter area we are crossing now firm mud, patches of swamp weeds, frequent puddles Moon, loping around aimlessly, blunders into a group of five or six snipe at the far side of a puddle, and I put trying to get a double out of my mind; I try to take my time: pick out an individual, follow him as he glides toward some high reeds and drop him.

Now we go along, towards the back of the marsh, shooting and missing, hitting just twice. One shot in particular pleases me: a snipe quite high, in full flight coming towards me. I shoot, remembering a phrase I once read: “A shotgun is a paint brush.” I paint the snipe blue, to match the sky, starting my brush stroke just behind him, painting evenly along his body, completing the stroke about three lengths in front where I fire, and follow through. This is a classic shot, a memorable one, so much so that there are just two others I can put with it—one on a faraway pheasant last year, one on a high teal in Chile. The sky is all blue now, for the snipe is painted out of it and falls, almost into my hand.

It is just 3:55.

There is magic in this. The end of the legal pheasant hunting day is four o’clock.

4:00 Just after the pheasant, I kill another snipe, the sixth. He is along the stream, too, and so I follow it, awed at the thought that I might even get a limit on these. But on the next chance, not a hard one, I think too hard, and miss the first shot, as he twists, and the rising one as well.

We leave the watercourse for a tiny marsh, go back to it (or a branch) through government fields I’ve never crossed before, by strange potholes and unfamiliar willow stands. We flush a woodcock, cousin to the snipe, but shooting him is not permitted here. We turn away in a new direction—snipe and woodcock favor different sorts of cover. And sometime along in there, I walk up two snipe, shoot one very fast, and miss a perplexing but not impossible shot at the other, as he spirals up.

“There he goes,” I think. “My limit bird.” He flies into the east, where the sky is getting dark; clouds have come to the western horizon and the sun is gone for the day, behind them.

5:03 In this remnant of perfect habitat, the sky is empty. It is five minutes till sunset, but it is dusk already, when my last snipe does go up, I hear him before I see him. I crouch down, close to the ground, trying to expand the area of light against which he will show up, and he appears now, winging for the upper sky; but I cannot decide to shoot, shouldering my gun in that awkward position. And in another second it is too late, really too late, and I feel as if the last hunter in the world has let the last snipe go without a try.

I straighten up reluctantly, unload gun, and wonder where I am. Suddenly I am tired, melancholy, and very hungry. I know about which way to go, and start along, calling Moon, only half lost, dragging a little. The hunting is over and home an hour away.

I think of quail hunting in Louisiana, when we crouched, straining for shots at the final covey, as I did just now for the final snipe.

I find a little road I recognize, start on it the wrong way, correct myself and turn back along it. A touch of late sun shows now, through a rift, enough to cast a pale shadow in front of me—man with gun—on the sand road.

We were on an evening march, in some loose company formation, outside of training camp. We were boys.

I watched our shadows along the tall clay bank at the side of the road. We were too tired to talk, even garrulous Bobby Hirt, who went AWOL later and spent two years, so we heard, in military prison. He was a boy. We all were. But the helmeted shadows, with packs and guns in silhouette, were the shadows of soldiers—faceless, menacing, expendable. No one shadow different from the other. I could not tell you, for after training we dispersed, going out as infantry replacements, which of those boys, whose misery and defiance and occasional good times I shared for 17 unforgotten weeks, actually were expended. Several, of course, since statistics show what they do of infantry replacements. Statistics are the representation of shadows by numbers.

My shadow on the sand road is of a different kind. I have come a little way in 19 years, whatever the world has done. I am alone, in a solitary place, as I wish to be, accountable only as I am willing to be held so, therefore no man’s statistic. Melancholy for the moment, but only because I am weary, and coming to the end of this day which, full of remembering, will be itself remembered.

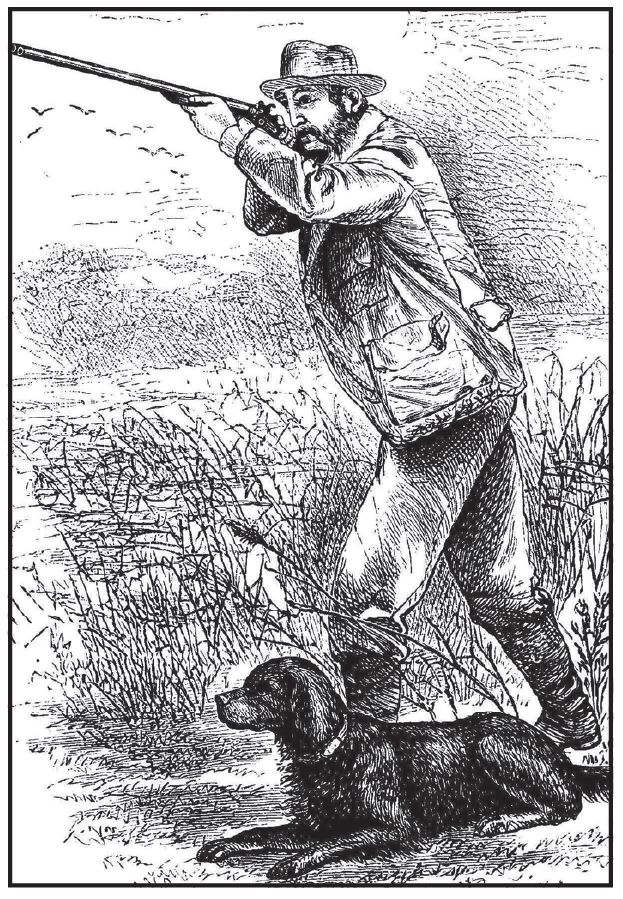

Moon is beside me, tired now too, throwing his own pale dog-shadow ahead. And the hunter-shadow with him, the pheasant hanging from the hunter’s belt, sniper bulging in the jacket—the image teases me. It is not the soldiers, but some other memory. An image, failing because the sun is failing, the rift closing very slowly. An image of. A hunter like. A dream? Not a dream, but the ghost of a dream, my old, hunter-and-hisdog-at-dusk dream. And the sun goes down, and the ghost with it, and the car is in sight that will carry us home.