Vengeance

The border post at Namanga comes up suddenly as you climb through the heat haze from the Tsavo plain of Kenya toward the sweeping highlands around Mount Kilimanjaro. Namanga itself isn’t much. A collection of ramshackle buildings, a scattering of trucks, a lopsided bus, and everywhere, like shifting flocks of tropical birds, the bright-beaded Masai in their crimson robes. There are a few trees, and under every tree in the dust is a seller of something: Beads. Pens. Pots. A few have board duccas thrown together—a two-foot counter fronting a one-shelf store. Those who aren’t selling are begging. When they crowd around, it’s hard to tell one from the other.

Years ago, every safari passed through Namanga, hot and dusty and two days out from Nairobi, heading for Arusha to draw licenses and have a cold beer at the Greek’s. Nobody does that anymore. Today the safari trade is airborne; sleek six-seaters whisk you from Nairobi’s Wilson Airport to Kilimanjaro in an hour; pay the bribes, pick up licenses, and continue on west by air. By sundown you’re in camp with a cold one in your hand and Tommies prancing on the plain. You don’t even hate the safari car. Not yet.

The border post at Namanga, deprived of the high-rent safari trade, has been reduced to shaking down busloads of package-deal tourists, who stand there looking helpless as they are deftly disencumbered of their loose belongings by the bony fingers of the crimson-dad crones who trade on their Masai appearance to ply city-bred skills. The old Africa hands avoid making eye contact, stride purposefully, and snarl hapana as they wade through the crowds to get their passports stamped. Sometimes it works. By the time you finally roll out of Namanga with Mount Meru looming in the distance, you truly feel you are in Tanzania—land of great beasts and grubby beggars, and more than enough of each.

When Tanzania gained its independence in 1963, the new government embraced a philosophy of crackpot socialism that over the next 30 years managed to undo what little economic progress the country had made in the last 100. On the social front, the newly minted politicians with their pseudo-Oxonian accents and Savile Row suits found their less-enlightened brethren rather an embarrassment, and none more so than the Masai. The Masai, with their spears and their buffalo-hide shields, their crimson cloaks and elaborate beads, their herds of cattle and lion-mane headdresses, were great for the tourists but bad for the image of a socialized society. In quick order, the Masai had their spears confiscated, their red robes banned, and their children locked up in school. In far-off Dar es Salaam, the politicians and United Nations do-gooders congratulated each other over cool ones on the veranda and discussed whose lives they could screw up next.

For 30 years the Masai in Tanzania lived under proscription. Their entire way of life—all the things that made them Masai, and hence made life worth living—had been legislated out of existence. The old men crouched in the dust and drank beer, and the lions went unhunted.

Then came the end of the old government. Julius Nyerere, darling of the aid agencies, retired to reflect on his accomplishments, and a new crowd took over a country that had become an economic basket case. Disenchanted with socialism, they unleashed free enterprise (or tried to) and backed it up with a more-or-less blanket endorsement of the old ways. Not many Masai would return to their traditional way of life anyway, they reasoned. Not after 30 years. What harm can it do? And so the proscription was lifted. Announcements went out.

Within days the spears had come out of mothballs and every scrap of red cloth had been swept from the ducca shelves. The elaborate blue, white, and red beads and head-dresses sprouted from every Masai head, and the school desks sat empty. The smiths on the plain stoked their forges to begin once again making the long-bladed spears and simis, the short swords that, together with shield and spear, announce to the world that this red-clad dandy is a blooded Masai moran.

It’s a funny thing about Tanzania: you can pull the Land Cruiser over to the side in the middle of nowhere, with nothing in sight for miles across the plain except dust devils, and within five minutes there will be a couple of urchins crowding around the truck with their hands out. Give it a couple more minutes and there will be a half-dozen locals begging for handouts. Even if you don’t pull over, when they see you coming in the distance they lock their eyes on yours and stand by the road with their arms straight out, palms upward, gaze unwavering as you roar on by, muttering. In Tanzania, begging at the personal, regional, and international level has been elevated to the status of national pastime.

But just when you think you’ve got that figured, you round a bend and see a Masai by the road. His hand is not out. It’s holding a spear, or fingering a simi, and if he stares at you at all it is down his long, straight nose. The Masai—the real Masai, not the sheep in wolf’s ’s clothing that infest Namanga—asks nothing from anyone except to be left alone with his herds and his flocks and his lion scars.

About 20 miles south of Namanga you are in the heart of Masai country. Mount Meru looms in the distance, and on the other side lies Arusha, the metropolis of the north; but here the plain stretches away with only the occasional spiral of smoke to indicate a dwelling. Off to the southeast, Kilimanjaro drifts in and out of its constant clouds and haze. As you drive, a line of hills appears on your left, rising starkly from the plain. It is not really a line of hills, though; it is the rim of a long-extinct and worn-down volcano called Mount Longido, which rises 3,000 feet from the Masai plain.

Eroded to a stump, Longido is dwarfed by its sisters, Mount Meru and Mount Kilimanjaro, and is now little more than a high crater encircled by steep, rocky hills. The crater is several miles across and grown over with trees. The name comes from the Masai Ol Donyo Ngito. Ngi is a type of black rock found on the mountain, and for centuries the Masai have climbed Longido to sharpen their spears and simis on the black rocks. The highest remaining point of Mount Longido is a sheer rock pinnacle like the prow of a ship. It is usually obscured by clouds, and on the higher slopes the thick brush turns to rain forest. From the upper reaches you can see all the way to the border post at Namanga, 20 miles north, and into Kenya as far as Amboseli National Park.

There is a Masai village, also called Longido, at the base of the mountain. It consists of a few buildings, a ducca, a police post. Under the spreading acacias, two saloons grace the main drag, which is nothing more than a wide spot in the dust. One establishment is called the Lion, the other the Vatican. The Lion is the more upscale of the two, which is to say it has a door. Right now the door to the Lion stands open and beckoning, and inside a stack of beer crates reaches to the low ceiling. The bar is a plank, and the seats are planks that run around the edge of the one small room. Two Masai moran in blinding red robes sit with a glass of ale, their spears leaning against the wall, discussing stock prices. They nod as we enter and do not stare overlong.

Ever since the army I have not been a lover of warm beer, but sometimes it isn’t bad. This was one of those times. Then we continued on out of town and around the base of the volcano and into our camp, on the southern slope facing Kilimanjaro far out across the Ngasarami Plain.

The plan was fairly simple. Mostly what people hunt around Longido are lesser kudu and some plains game. Sometimes they venture up the outer slope in hopes of a klipspringer, but mountain climbing in the heat is not a lot of fun, and as you get higher the going gets rougher. Like most mountains, it looks a lot easier from a distance.

Longido is shaped like a huge bowl. There are one or two passes where you can climb up over the hills and down into the crater, and in some spots these hills rise higher and higher, eventually simulating real mountain peaks, shrouded in cloud with rain forest and heavy mists. The crater is several miles across; a few Masai live up there and raise crops in the crater, carrying on a running battle with the baboons who raid from the forested hillsides. The Masai run their cattle on the hillsides as well, sharing the sparse grazing with a few dozen Cape buffalo. Rumor had it that high on Mount Longido there lurked a few buffalo bulls, too old to breed, too cantankerous to associate with, living out their lives alone. A few people had been up there and seen tracks. That was all. But they were big tracks. I had hunted Cape buffalo waist-deep in swamp water and dry as dust in sand and thornbush. Why not on a mountain top?

Cape buffalo-hunting today consists all too much of roaming around in a safari car. No one we knew of had ever climbed Mount Longido looking for a big old bull off by himself on a distant mountainside, but preliminary investigation suggested there might well be a good one up there if we were willing to sweat. Jerry Henderson thought that hunting such a bull would make good publicity for his new-found safari company and reminded me in his soft Texas tones that I like mountain hunting.

Sure enough, I do. And sure enough, I will. The company had a small group of very good professionals from Zimbabwe—Gordon Cormack, Duff Gifford, and a third I will just call Frank. Frank was a youngster of Afrikaner stock, and he was to be my PH when Jerry and I went off up the mountain. Jerry had dispatched him earlier to go up and look around, and Frank had returned determined that once was enough, although he did not say it in so many words. Instead, he decided the best way out was to discourage me from going up there. One conversation with Frank was enough to persuade me that I wanted no part of hunting Cape buffalo with someone I didn’t trust, and it was obvious, as he lectured me on the perils of mountain hunting, that he himself did not want to go up that mountain.

“I’ll go,” I told Jerry. “I want to go. It can’t be any steeper than the Chugach, or any thicker than coastal Alaska. But I ain’t going with him.”

Frank, to his relief, was out. Duff Gifford, to my relief, was in. The next morning we rolled out of camp and edged along the base of the mountain toward the winding trail up and over the hills to the Masai settlement in the crater.

Our party looked, as we made our laborious way up the mountainside, much like those porter safaris from Teddy Roosevelt’s day. In addition to Duff, Jerry, and me, we had our cook and camp boy, both laden down with equipment. A couple of Masai retainers trailed along as well. Then there was the government game scout, Swai, a grinning citizen of legendary corruption who was based in Longido. By law we had to have him along; by custom he surrounded himself with his own retinue of flunkeys, including a gunbearer, a gunbearer’s assistant, and who knows what all. Altogether, we had a dozen people strung out along the dry watercourse that cut through the thick brush on the mountainside and afforded the easiest route over the hills and down into the crater.

We reached the Masai huts around noon with the sun directly overhead and overbearing as only the equatorial sun can be. We flopped down under an acacia while Swai went off to negotiate with the locals. While we waited they brought us tea and maize, scorched by the fire and not half bad. When Swai returned, he brought with him three Masai to guide us. They wore their working clothes—gym shorts and spears. Ceremonial garb is fine for standing around wowing the tourists, but climbing a mountain in search of buffalo calls for something a little more practical. We divided up the baggage, formed a line, and swung on up the mountain.

To anyone accustomed to the Chugach, or any of the mountains of the American West, the going was not that hard. It was steep in places, and stony, but there were trails through the thorn brush where generations of goats and cattle and buffalo had browsed. The worst part was the heat. The sun was a physical weight on our shoulders as we struggled upwards, panting and sweating. The Masai suffered not at all, moving ever upwards in a loose, swinging gait, bare feet oblivious to rocks and thorns, bare shoulders shrugging off the sun.

Below us the Masai settlement was soon reduced to a few dots and postage-stamp fields, and we were high enough to look out across the crater. The peaks still loomed above, but the ancient volcano had lost its shape and unity, and we felt as though we were climbing among jumbled hills. There were ravines and gullies overgrown with a jungle of tangled brush. There were boulders that blocked our path as we wended our way back and forth, ever upward toward a high meadow that bordered a patch of rain forest just below the peak. There we would camp and, with luck, glass the hillsides below for a glimpse of buffalo.

We reached the meadow in late afternoon and made camp—a couple of small tents and a fire pit. Dinner was a laudable effort under the circumstances, eaten around the fire in the chill brought on by the sudden darkness of the equatorial night. Then our cook produced a precious few ounces of Scotch—barely enough for a sniff apiece, but it lent the illusion of a safari camp—and Duff and Jerry and I sat around our cheerful little blaze talking guns and buffalo and mountains.

That night was one of the coldest and most miserable I can remember. With darkness the temperature plunged and the rain came. We had no bedding—a slight mixup—and I spent the hours huddled on the damp plastic of the tent floor with the stock of my Model 70 for a pillow. I didn’t know it at the time, but the sheer misery of that cold, wet night on the mountain was to prove a great benefit to us.

As soon as the sky turned grey I crawled out into a soupy mist that swirled and drifted and soaked the air as the rain had soaked the grass. Everyone was gathered around the fire, which smoked and hissed as it tried to produce enough heat to boil water. A more forlorn looking group I have never seen in a hunting camp. Swai, the game scout, huddled close to the tiny flame wrapped in an army blanket with his teeth chattering and his retainers bunched close around. Duff handed me a coffee and smiled his wolfish smile. The wet misery of the mountainside had robbed him of none of his assurance.

“Shall we go take a look?”

“In this stuff?”

“It’ll clear. We want to be out there when it does.”

Duff said a few words to Swai, who mumbled in response but made no move to leave the warmth of the fire.

“Is he coming?”

“Not right now. I told him we’re just going to glass. No need to disturb himself.” The wolfish smile again.

Duff and Jerry and I gathered our rifles and binoculars and picked our way through the grass along a ridge to a rocky promontory. The fog was shifting now, swirling gently at first, then a little stronger. Somewhere up there the sun was rising and bringing with it a breeze, and soon that breeze would become a wind and clear the fog away for good. Meanwhile, we could see little and do nothing but wait. But at least we were waiting alone.

For those who have not had the pleasure, hunting in Tanzania is, by law, a group activity. By law, you must have a game scout with you at all times. By the letter of the law, that means all times. No self-respecting game scout, however, goes out alone. He needs at least as many retainers as the professional hunter has, to show his equality. So if the PH has two trackers and a boy to carry the water jug, the game scout needs at least three flunkeys and preferably four. That adds up to a hunting party of ten, traipsing through the bush and scaring the wildlife.

In hunting, one is company and two is pushing it. Hunting with a cast of thousands, all arguing about what the tracks mean and debating whether we should go left or right, critiquing bwana’s shooting and generally having a hell of a time, is not my idea of a perfect hunting scenario. If the game scout insists on coming, though, you don’t have much choice.

Now we found ourselves, thanks to that blessed, wonderful, beautiful mist and rain and cold, allowed to leave camp unencumbered while Swai the Ungodly attempted to thaw himself out. And if Swai did not need to venture forth, neither did anyone else. For us, it was like being let out of school early.

The slopes of Mount Longido are cut by dozens of ravines carved by centuries of torrential rains. Some are so deep they could be called canyons, others are just dongas, but all are overgrown with vegetation and jumbled with boulders. We found a lookout and settled in, each watching a different valley. It was like being high up in an enormous stadium—or would have been but for the thick, shifting fog. We shivered and waited. A sporadic wind began to blow. The clouds came and went, clearing one minute, enveloping us the next. It was during one of these brief clear moments that I happened to catch sight of a grey-black object disappearing into some brush on a far hillside. Just a quick glimpse, and then the fog rolled back in.

“Duff, I saw one,” I said, not quite sure I really had. Maybe all I had seen was a rock. But when the fog drifted away again, there was no grey rock right there. It must have been a buffalo. He had shown himself in a clearing for a split second at the precise moment a window had opened in the fog, and I just happened to have my binocular trained on the spot.

We sat and willed the fog to clear. By now it was 9:30; the sun was well up and the rising wind made short work of what was left of the clouds. The slopes and the crater were all in plain sight, and for half an hour we studied the hillside across the valley. For Duff and Jerry, I pinpointed as best I could where I thought I had seen the buffalo disappear. There was the bare face of a large boulder just to the right of the spot. That was the only real landmark in the hodgepodge of brush. As the minutes passed, I became less and less sure. Had I really seen a buffalo? Had I really seen anything?

“What’d you see, exactly?”

“Just the back end, and just for a second.”

“Which way was he moving?” Duff is from Zimbabwe, and his Rhodesian voice was clipped and military as he gathered information. But he seemed to have no doubts.

“Along the hillside, from left to right. About halfway up.”

Half an hour went by. By that time I was almost convinced I had been hallucinating. When the buffalo did not reappear, Jerry wandered back to watch the other valley.

“I’ve got an idea,” I said to Duff. “Let’s have Jerry stay here to spot for us, and you and I go down and look for him.” Duff grinned. “Sounds good to me,” he said, and padded off to get Jerry.

“We’ll cross straight over to the hillside and use that tree as a start line,” Duff told him, pointing to a bare-trunked acacia that rose taller than the others. “When we get there, we’ll work straight along toward the big boulder on the right. If you see us get off course in that thick stuff, signal. Or if you see the buffalo . . .”

Jerry nodded a quick assent, gave me a clap on the shoulder, and a soft, Texan “Good luck.” Then we dropped down the steep hillside with Duff leading. Almost immediately we came upon a scraped-out hollow. The musky urine smell of buffalo hung in the air, and we found hoof prints the size of dinner plates. “Well, we know there’s one here,” Duff whispered. “Big old boy, too.”

We continued down along one of the bull’s established trails. There was a wart hog skull under a bush and, a few feet away, one of its ivory tusks, slightly rodent-chewed. I put it in my pocket for luck.

We were across a creek bed and climbing again. Now we could look back and see Jerry perched high on the rock opposite, watching us. Through the binocular, he gave a thumbs up. We were on course and almost immediately found the bare-trunked tree. A clearing stretched along the slope in front of us, and at the far end I could just make out the big rock face.

It was approaching 10:30. The sun was high, and the air had warmed. I was sweating in my goosedown shirt. Worse, it was noisy, catching on every thorn and twig. I tore it off and stuffed it into my belt. Duff, in shorts and khaki vest, moved through the brush like a leopard, and his cropped hair and compactly muscled shoulders reinforced the image. We were edging along the clearing now, a few feet apart, communicating by signs and instinct as if we had hunted together for years.

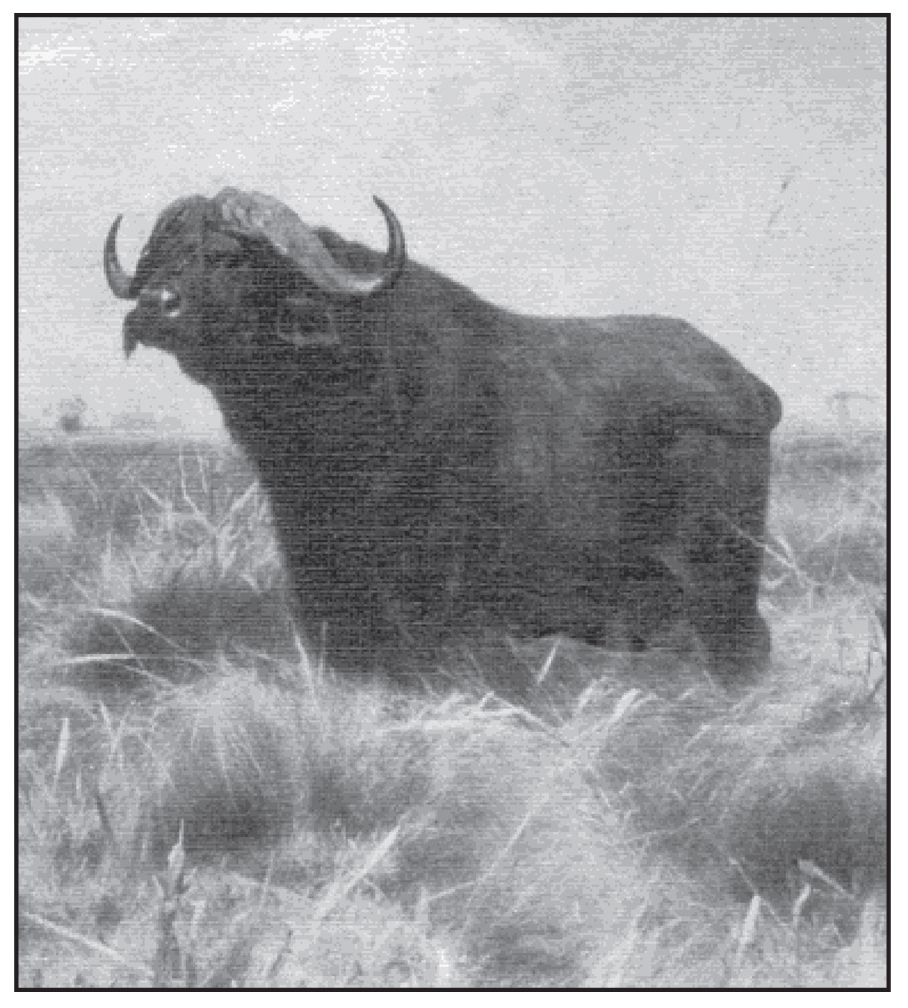

He was watching for tracks and I was looking past his shoulder when the bull stuck his head out of the bushes about 150 yards in front of us, right beside the boulder. I hissed and pointed. We froze. The buffalo had not seen us. He swung his head from side to side, and the boss of his horns was so big it made his horns look stubby, but they were not. His boss was heavy and black and met on the top of his skull without a gap. He was, indeed, a big old boy.

The bull looked around, then slowly withdrew into his sanctuary. We breathed again and melted into the thick brush out of sight.

“He’s big, he’s wide,” Duff whispered. “You want him?”

“I sure do.”

We crawled along inside the screen of brush until we came up against a large rock, then crept back up to the clearing. We found ourselves on the edge of a deep donga jammed with a jungle of scrub. On the other side, 60 yards away, was the rock face where we had seen the bull. This was as close as we were going to get.

“Can you shoot from here?”

I nodded, found a clear spot to sit down, jacked the scope up to four power and wrapped the sling around my arm. Just as I leaned forward the big buffalo came out again, right on cue. He seemed to be going somewhere. I put the crosshair on his shoulder and squeezed. As the .458 bucked up into my face, the bull hunched and roared and dashed down into the donga, deep into the thickest of the thick brush.

“Shoot again,” Duff yelled, but there was no time, and then the bull was out of sight. We could hear him, moving around down in the donga a few yards away. Then the rustling stopped and all we heard was his breathing, heavy and rasping. We stood together on the lip of the donga, looking down into the undergrowth. I replaced the spent cartridge in the magazine of the Model 70 and turned the scope down to one. Then we waited.

“He’s hard hit,” Duff said. “He blew blood out his mouth as soon as you shot. Hear him?”

From the brush, the sound of heavy panting came to us. He was no more than 15 yards away, maybe less.

“Hear him? Can you hear him? He’s kuisha,” Duff said. “Finished. That was a good shot, bwana. You got him in the lungs. We’ll give him ten minutes, see what happens.”

We stood side by side, trying to pierce the brush with our eyes, listening to the harsh breathing, waiting for the long, drawn-out bellow that would signal the end. But the only sound from the donga was the rough grating of each painful breath, in and out, in and out, in and out.

The old bull had lived alone on the mountainside for many years. There was a small herd of younger Cape buffalo up there, too, cows and calves and bulls, maybe a dozen in all, but they wanted nothing to do with him and they avoided his valley. He bedded on a slope overlooking the crater and each day visited the creek that bubbled down the mountain, then browsed up and along his favorite hillside as he made his way toward his own special place.

There was a boulder there, and some thick acacias, and in the shadow of the boulder it was cool for him to doze through the heat of the day. On one side was a donga and a narrow trail that led down into it and back up out of it. He crossed through that donga each day. Although the brush looked as solid as a wall, with his four—foot horns he could force his way through.

On this day, as the clouds cleared (cleared as they did almost every day up here, away from the plain, away from the big buffalo herds) the old bull sensed there was something wrong. He caught a whiff of something—smoke, perhaps—but there was no smoke on the mountain; the Masai stayed down in the crater, and the smoke from their fires rarely drifted this far up.

But there was something, something; once or twice he emerged to look along his backtrail before withdrawing back into his hideaway. Finally, he decided he would climb the bill to a better vantage point. As he came out he caught it again, that scent—not leopard, not Masai—a scent he had known only once or twice before in his long life, and just as he quickened his pace he was slammed in the ribs and a tremendous roar slapped his head and a cough was forced out of his lungs by the impact of the bullet and blood sprayed from his mouth.

Involuntarily he bucked and sprang. His trail was at his feet, the familiar trail down into the donga, and he let it carry him into the friendly gloom. Once there, he paused. His head was reverberating from the crash of the rifle and he could feel his breathing becoming heavy as a huge vise tightened on his chest. From the embankment above came the murmur of voices, and his rage began to build as his lungs filled up with blood.

The bottom of the donga was a tunnel through the vegetation, scoured clean of debris when the heavy rains came. The old bull slowly walked a few yards up the creek bed, then turned and lay down facing the trail. On each side of him were high earthen banks, and over his head was a roof of solid vegetation. They would have to come down that trail. He fixed his eyes on it, six feet away. Now let them come.

And there he waited as blood spurted out the bullet hole, his heart pumping out a bit of his life with each beat. Each breath came a little shorter, and the pool of bright red blood under his muzzle spread wider, and his rage grew inside him like a spreading fire. He heard them whisper “Kuisha . . . ” Well, not just yet. And he heard them say “Give him ten minutes . . . ” Yes. Ten minutes. He was old and he was mortally wounded. But he was not dead yet. The old bull fixed his gaze on the trail and concentrated on drawing each breath, one by one, in and out, in and out.

The minutes ticked by: three, four, seven, eight.

Duff and I waited on the bank. Only the wounded buffalo’s rasping breath broke the silence on the mountainside.

“I know you want to see . . . ” Duff whispered.

“Not me, bwana,” I answered. “I can wait here forever.”

“When you hear him bellow . . . ” he began.

The old bull watched as the pool of blood grew and he felt himself growing weaker. Ten minutes. They weren’t coming. Not much time left now. He heaved himself to his feet and a gout of blood poured from his mouth.

The bull could have eased silently down the donga and died, off by himself. But he did not want to go quietly. He wanted to take those voices with him. And since they would not come to him . . .

He bunched his muscles and sprang, charging up the trail. His horns plowed through the brush and shook the trees. He could not see them yet, but he was coming hard. There was not much time, and he had to reach the bated voices.

“He’s moving, get ready!” Duff yelled.

We saw the brush trembling and his hoofs rocked the hillside, but we could not see the bull. Not yet. He was only yards away and moving fast, but where would he come crashing out? We couldn’t see a damned thing. And then a black shape burst from the bushes five yards down and to my right.

“Shoot!”

I tried to get the scope on him, but all I could see was black. I fired, hoping to catch a shoulder, then worked the bolt and Duff and I fired together.

As we did, the bull turned his head toward us. His murderous expression said, “Oh, there you are!” and his body followed his head around. I was between Duff and the buffalo, and the buffalo was on top of me, and all I could see was the expanse of horn and the massive muscles of his shoulders working as he pounded in.

No time to shoulder the gun now—just point and shoot and hope for the best. I shoved the .458 in his face and fired as I jumped back, and the bull dropped like a stone with a bullet in his brain, four feet from the muzzle of the rifle.

“Shoot him again!” Duff shouted. “In the neck!”

“With pleasure,” said I, weakly, and planted my last round just behind his skull.

Duff and I looked at each other.

“We’re alive!”

We gave the meat to our Masai guides, and they brought the skull and cape down the mountain for us the next day. It took three hours to skin him out. They built a fire, and we roasted chunks of Cape buffalo over the flames as the skinner worked, carving off bites with our belt knives and tossing the remains to the Masai dogs. The meat was tough, but juicy and rich tasting. Duff and I ate sparingly and chewed long. If you are what you eat, we were one mean bunch of bastards when we came down off that mountain.

Then the reaction set in. For two days I did little except stay in camp, sometimes talking, but mostly just off by myself. I set up a camp chair in the shade where I could catch the breeze through the day and look out across the plain to the smoke rising off the slopes of Kilimanjaro. I had a well-worn copy of Hemingway that has travelled with me around the world, and it was then I discovered that there are times when you cannot read. Mostly I just sat and stared at Kilimanjaro in the distance, or rose and walked to the edge of our camp and looked back up the slopes of Mount Longido.

In the first split second when my buffalo burst from the bushes, I thought he was the most wonderful creature that ever lived, and when he dropped at my feet with a bullet in his brain and his eyes still open and fixed upon me, at that moment I knew a thousand times more about Cape buffalo than I had even minutes before.

We were driving back into camp late one afternoon when a brightly clad Masai elder flagged us down. A roving trio of lions, two young males and female, had killed a cow that afternoon. The dead animal was in the brush, guarded by four morani who had driven them off the kill with spears. Could we help them get the cow back to their village?

By the time we got there, nosing gingerly through the brush with Duff at the wheel and me riding shotgun with my now thoroughly beloved .458, it was pitch black. Our headlights picked up a Masai, waiting for us in the bush beside the dirt track to guide us in. The Land Cruiser forced its way through and over the thorny acacias to a tiny campfire beside the dead cow and four heavily armed Masai, standing in the darkness with three hungry lions somewhere nearby.

They hauled and heaved the carcass up into the back, and Duff put the Land Cruiser in gear. As the headlights swung in an arc, they picked up three pairs of eyes in the bush not 20 yards away. The lions had not gone far. As we pulled out onto the track, we met two Masai youngsters swinging along the road, armed like their elders with tiny spears and scaled down swords, driving two donkeys ahead of them, coming to start ferrying the beef back to camp if we had not shown up. Two little boys with two little spears, driving two tiny donkeys through the darkness, with three hungry lions lying up somewhere in the bush nearby. Three hungry and bitterly disappointed lions who, to the best of our knowledge, never did get a meal that night. Standing up in the back with the .458, I suddenly felt a little foolish.

The door of the Lion was still open and beckoning when we pulled into Longido the next day. Beer crates still reached to the ceiling, and the propane refrigerator was still not working. We had a beer anyway.

Three Masai in full regalia sat in the bar with their spears against the wall, drinking Tusker and discussing stock prices. We bought them a beer, and they gravely returned the favor. A few days later, bribing my way back out of the country at Namanga, a scarlet-robed native pawed at me and begged for alms, all the while proclaiming, “I am Masai!” To which I replied, “Like hell you are, bucko.”

Epilogue

About a year later, an envelope arrived in the mail with a Houston postmark. Inside was a newspaper clipping from The Daily Telegraph with the headline, “Peer’s Son Killed By Charging Buffalo,” and the story of how Andrew Fraser, the youngest son of Lord Lovat (of World War Two commando fame) had been charged and killed while on safari near Mount Kilimanjaro.

“Mr. Fraser shot and wounded the buffalo, but it took cover in thick bushes from where it made its charge, tossing him and causing severe injuries,” it read. The clipping was dated March 17, 1994—one year to the day after our encounter on Mount Longido.

In the margin was a note: “ Terry, does this sound familiar? Jerry.”