The Classic Fall-on-Your-Arse Double

As I write this, it’s dead, dreary winter in Vermont—a foot of squeaking, crusted snow on the ground, with the barn thermometer registering well below zero at sunup and rarely topping 20 degrees on even the sunniest days. Gloom prevails. The bird season is quits until next fall and my major outdoor activity is lugging in cartloads of frost-crusted logs to feed the insatiable woodstove. As always during these bleak times of year, my memories turn to warmer climes and skies full of fast-moving gamebirds. Some of the best shooting I ever enjoyed occurred in Kenya, back in the 1960s and ‘70s, the last years of East Africa’s golden era as a hunting venue. Here’s a taste of it:

The big Bedford lorries had arrived the day before, so by the time we wheeled into the campsite along the Ewaso Nyiro River the tents were up—taut, green, smelling of hot canvas and spicy East African dust. It was a sandy country, red and tan, and the river rolled silently but strong, dark almost as blood, under a fringe of scrawny-trunked doum palms and tall, time-worn boulders. Sand rivers cut the main watercourse at right angles, and the country rolled away to the north and west in a shimmer of pale tan haze. The fire was pale and the kettle whistled a merry welcome.

This was the last camp of the month-long shooting safari through Kenya’s arid Northern Frontier Province, a hunt that had begun three weeks earlier at Naibor Keju, in the Samburu country near Maralal, then had swung northward through the lands of the Rendile and Turkana tribes to Lake Rudolf and back down across the Chalbi and Kaisut deserts past Marsabit Mountain to the Ewaso Nyiro.

“I call it EDB,” Bill Winter said as we climbed down out of the green Toyota safari wagon. “Elephant Dung Beach. The first time I camped here the lads had to shovel the piles aside before we could pitch our tents, it was that thick. Ndovus everywhere.”

Not anymore. On the way in from Archer’s Post, Bill had pointed out the picked skeleton of an elephant killed by poachers—and not long before, judging by the lingering smell. We’d stopped to look it over—vertebrae big as chopping blocks, ribs fit for a whaleboat, the broad skull still crawling with ants, and two splintered, gaping holes where the ivory had been hacked out.

“Shifta,” Bill had said, and when we got into camp the safari crew confirmed his diagnosis. Shifta were even then the plague of northeastern Kenya, raiders from neighboring Somalia who felt, perhaps with some justification, that the whole upper right hand quadrant of Kenya belonged to them. When the colonial powers divided Africa among themselves, they all too often drew arbitrary boundaries regardless of tribal traditions. The Somalis—a handsome, fiercely Islamic people related to the Berbers of northwest Africa and the ancient Egyptians (theirs was the Pharaonic “Land of Punt”)—were nomads for the most part, and boundaries meant as little to them as they do to migrating wildebeest. But these migrants armed with Russian AKs and plastic explosives had blood in their eyes. They poached ivory and rhino horn, shot up manyattas (villages) and police posts, mined the roads and blew up trucks or buses with no compunction. Sergeant Nganya, a lean old Meru in starch-stiff Empire Builders and a faded beret, led us over to a lugga near the riverbank. In the bottom were the charred, cracked leg bones of a giraffe, scraps of rotting hide, the remains of a cook fire and an empty 7.62mm shell case stamped “Cartridge M1943”—the preferred diet of the Soviet AK-47 assault rifle. Nganya, who had been with Winter since their days together in the Kenya game department, handed the shell over without a word.

“I’m sure they’ll leave us alone,” Bill said as we drank our chai under the cool fly of the mess tent. “They know we’re armed, and the lads will keep a sharp lookout around the camp. Just to ensure sweet dreams for one and all, though, I’ll post guards at night. Not to worry.”

We would finish out the safari with some serious bird shooting. It was a welcome relief, a slow, leisurely cooling-out from the high tension and dark tragedy of big game, and for me doubly so because bird hunting has always been my first love among the shooting sports. But this was a different kind of bird hunting: I’d grown up on ruffed grouse, woodcock, sharptails and pheasants in the upper Middle West, and that kind of gunning had meant cold mornings, iron skies, crisp wild apples, the crunch of bright leaves under muddy boots. It had been all tamaracks and muskegs, old pine slashings, glacial moraines and ink-black ponds. In the one-horse logging towns we’d whiled away the evenings on draft beer, bratwurst and snooker. The great unspoken fear in that land of Green Bay Packer worship hadn’t been shifta but something far more fearsome, in those days at least: the Chicago Bears.

The contrast between American and African bird shooting became quickly clear. We were up before dawn, but even this coolest part of the day was T-shirt weather. Hyenas giggled downriver and a great fish eagle winnowed the air overhead as we sipped strong Kenya coffee at first light. There were lion tracks outside the tents, fresh ones—great bold pug marks that circled the camp twice, evidently made during the night. But our guards, the wry Turkana named Otiego and the big, slab-faced Samburu we called Red Blanket, reported no signs of shifta during their watches. Yet they hadn’t seen the lion either. . . .

Not far from the river was a hot spring, a maji moto in Swahili, and we walked in quietly through a low ground fog, armed only with 20-gauge shotguns. Soon the sand grouse would be flying. Lambat lead the way, peering intently into the mist. He raised a hand: Halt. We heard a huffing sound in the fog, then dimly made out two dark bulky shapes. “Kifaro,” Lambat hissed. “Mama na mtoto.”

Either the fog thinned or adrenaline sharpened my vision, for suddenly they came into focus: a big female rhino and her calf. The mother whuffed again, aware that something was wrong but unable with her weak eyes and the absence of wind to zero in on the threat. She shook a head homed like a Mexican saddle and shuffled off into the haze followed by her hornless offspring, which looked at this distance like an outsized hog. I’d often jumped deer while bird hunting in the US, and once a moose had gotten up and moved out of an alder swale I was pushing for woodcock near Greenville, Maine. But rhinos are somehow different. If only for the heightened pucker factor.

The sun bulged over the horizon, a giant blood-orange, and instantly the fog was gone, sucked up by the dry heat of the day. But then it seemed to return, in the whistling, whizzing form of a million sand grouse, chunky birds as quick and elusive as their distant relatives, the white-winged doves and mourning doves I’d shot back home.

These were chestnut-bellied sand grouse, Pterocles exustus, the most common of some six species that inhabit the dry thorn scrublands of Africa. They fly to water each morning, hitting the available waterholes for about an hour soon after dawn, fluttering over the surface to land, drink and soak up water in their throat feathers for their nestlings to drink during the dry season.

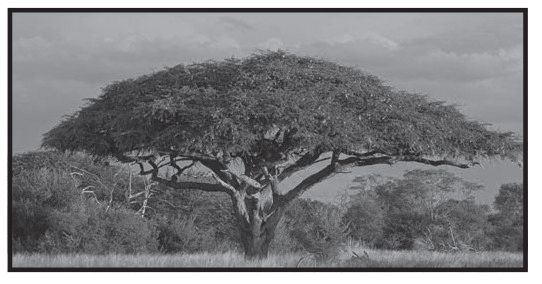

I promptly began to miss them, overwhelmed and wild-eyed at their sky-blackening abundance. Then I settled down as the awe receded and began knocking down singles and doubles at a smart clip. It was fast, neck-wrenching shooting, with the birds angling in from every direction. I stood under the cover of an umbrella acacia, surrounded by shell husks, the barrel of my shotgun soon hot enough to raise blisters, shooting until my shoulder grew numb. Bill stood nearby, calling the shots and laughing at my misses.

“Quick, behind you, bwana!”

I spun around to see a pair of sand grouse slashing in overhead, mounted the gun with my feet still crossed, folded the lead bird and then leaned farther back to take the trailer directly above me. Pow! The recoil, in my unbalanced, leg-crossed stance, dropped me on my tailbone. But the bird fell too.

“Splendid,” Bill said with a smirk. “Just the way they teach it at the Holland & Holland Shooting School. The Classic Twisting, Turning, High-Overhead, Passing, Fall-on-Your-Arse Double. Never seen it done better, I do declare!”

Then it was over. The sand grouse vanished as quickly as they had appeared. The trackers began to pick up the dead birds and locate any “runners.” There were few wounded birds. I’d been shooting No. 6s, the high-brass loads we’d used earlier in the safari for vulturine and helmeted guinea fowl. The heavy shot had killed cleanly when I’d connected. We could have used No. 7½ shot, perhaps even 8s on these lightly feathered, thin-skinned birds and increased the bag a bit, but there really had been no need to. By using heavier shot, we’d ensured swifter kills, and there never had been a dearth of birds.

Or so I was thinking. Just then one of the birds—a cripple, far out near the whitescaled salt of the hot spring’s rim—scuttled away, trailing a shattered wing. Lambat stooped like a shortstop fielding a line drive, grabbed a stone and slung it sidearm. It knocked the bird dead at 20 yards. He picked up the grouse and brought it to me, walking long and limber, dead casual, a look of near-pity on his face as he placed it in my hand. Ah, the sorry, weak Mzungu with his costly firestick, blasting holes in the firmament with those expensive shells, when there were rocks right there for the picking. “His lordship,” indeed.

Reprinted with permission of Louise H. Jones.