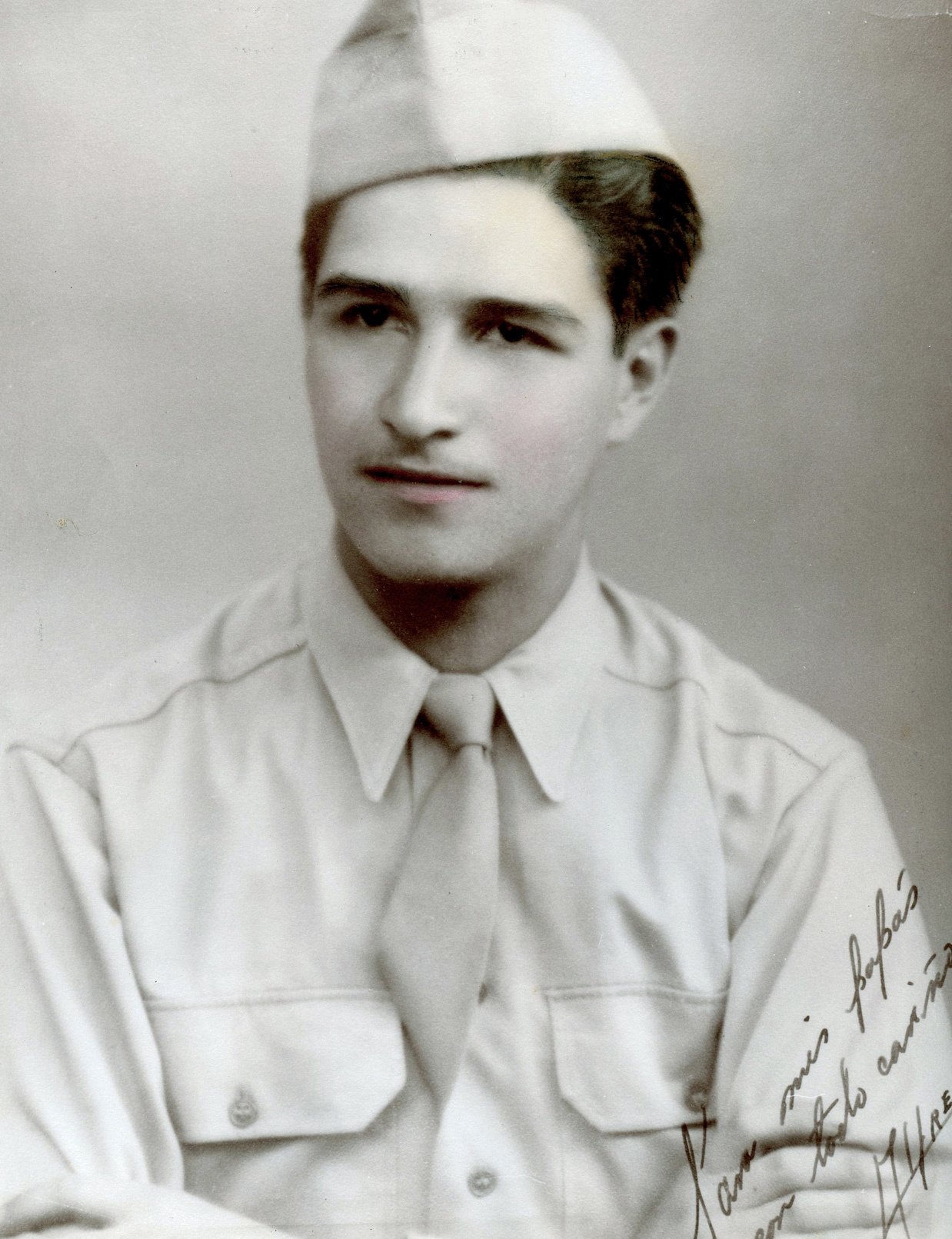

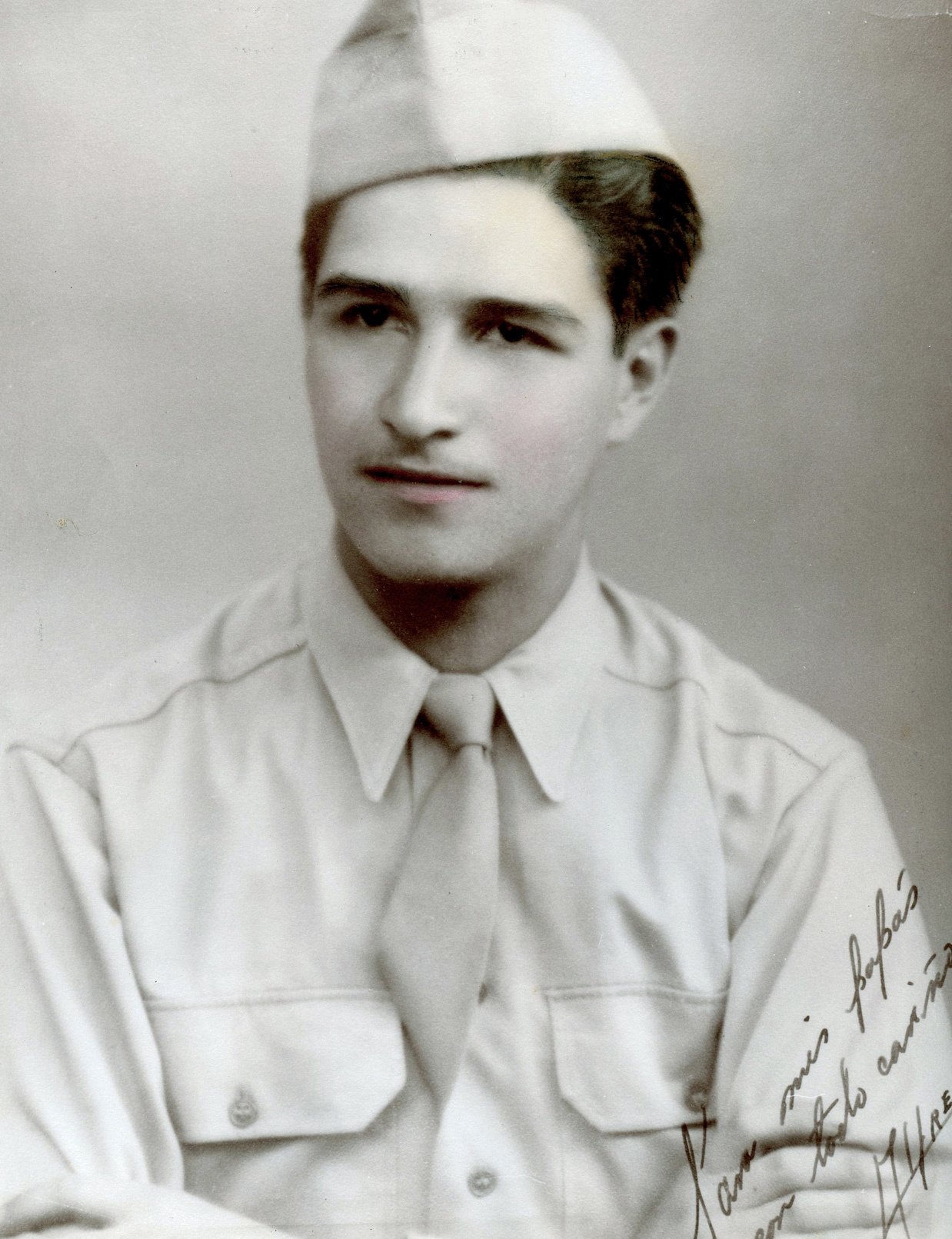

My personal altar for my father

My personal altar for my father

This story came of its own accord, uncommissioned, though I was to first publish it in the Los Angeles Times, on October 26, 1997, and the San Antonio Express-News, on November 2, 1997. At the same time I created an altar for my father in my home since it was the first Day of the Dead after his death. Later I would write an ofrenda and install an altar for my mother when her time came. Both story and altar served the same purpose: nourishment, clarity, and transformation at a time when my spirit was dying.

Mi’ja, it’s me, call me when you wake up.” It was a message left on my phone machine from my friend José De Lara. But when I heard that word “mi’ja,” a pain squeezed my heart. My father was the only one who ever called me this. Because my father’s death is so recent, the word overwhelmed me and filled me with grief.

“Mi’ja” (MEE-ha) from “mi hija” (me EE-ha). The words translate as “my daughter.” “Daughter,” “my daughter,” “daughter of mine,” they’re all stiff and clumsy, and have nothing of the intimacy and warmth of the word “mi’ja.” “Daughter of my heart,” maybe. Perhaps a more accurate translation of “mi’ja” is “I love you.”

With my father’s death the thread that links me to my other self, to my other language, was severed. Spanish binds me to my ancestors, but especially to my father, a Mexican national by birth who became a U.S. citizen by serving in World War II. My mother, who is Mexican American, learned her Spanish through this man, as I did. Forever after, every word spoken in that language is linked indelibly to him. Can a personal language exist for each human being? Perhaps all languages are like that. Perhaps none are.

My father’s Spanish, particular to a time and place, is gone, and the men of that time are gone or going—Don Quixote with a hammer or pick. When I speak Spanish, it’s as if I’m hearing my father again. It’s as if he lives in the language, and I become him. I say out-of-date phrases that were part of his world. Te echo un telefonazo. Quiúbole. Cómprate tus chuchulucos. ¿Ya llenaste el costalito? Que duermas con los angelitos panzones.

There is stored in my father’s Spanish, the way a spider might be sealed in amber, a time and place frozen just out of reach, but that I can hold up to my eye to make the world more golden. Intrinsic in Mexican Spanish is a way of looking at all things in the cosmos, little or large, as if they are sacred and alive. The original indigenous languages may have disappeared, but not the indigenous worldview. This native sensibility transposes itself into the English I write.

As a writer, I continue to analyze and reflect on the power words have over me. As always I’m fascinated with how those of us who live in multiple cultures and the regions in between are held under the spell of words spoken in the language of our childhood. After a loved one dies, your senses become oversensitized. Maybe that’s why I sometimes smell my father’s cologne in a room when no one else does. And why words once taken for granted suddenly take on new meanings.

When I wish to address a child, a lover, or one of my many small pets, I use Spanish, a language filled with affection and familiarity. I can liken it only to the fried-tortilla smell of my mother’s house or the way my brothers’ hair smells like Alberto VO5 when I hug them. It just about makes me want to break down and cry.

The language of our antepasados, those who came before us, connects us to our center, to who we are, and directs us to our life-work. Some of us have been lost, cut off from this essential wisdom and power. Sometimes our parents or grandparents were so harmed by a society that treated them ill for speaking their native language, they thought they could save us from that hate by teaching us to speak only English. Those of us, then, live like captives, lost from our culture, ungrounded, forever wandering like ghosts with a thorn in the heart.

When my father was sick, I watched him dissolve before my eyes. Each day the cancer that was eating him changed his face, as if he were crumbling from within and turning into a sugar skull, the kind placed on altars for Day of the Dead. Because I’m a light sleeper, my job was to be the night watch. Father always woke several times in the night choking on his own bile. I would rush to hold a kidney-shaped bowl under his lips, wait for him to finish throwing up, the body exhausted beyond belief. When he was through, I rinsed a towel with cold water and washed his face. “Ya estoy cansado de vivir,” my father would gasp. “Sí, yo sé,” I know. But the body takes its time dying. I have reasoned since then that the purpose of illness is to let go. For the living to let the dying go, and for the dying to let go of this life and travel to where they must.

Father at the hospital, October 1996

Whenever anyone discusses death they talk about the inevitable loss, but no one ever mentions the inevitable gain. How when you lose a loved one, you suddenly have a spirit ally, an energy on the other side that is with you always, that is with you just by calling their name. I know my father watches over me in a much more thorough way than he ever could when he was alive. When he was living, I had to telephone long distance to check up on how he was doing, and if he wasn’t watching one of his endless telenovelas, he’d talk to me. Now I simply summon him in my thoughts. Papá. Instantly I feel his presence surround and calm me.

I know this sounds like a lot of hokey new-age stuff, but really it’s old age, so ancient and wonderful and filled with such wisdom that we have had to relearn it because our miseducation has taught us to name it “superstition.” I have had to rediscover the spirituality of my ancestors, because my own mother was a cynic. And so it came back to me a generation later, learned but not forgotten in some memory in my cells, in my DNA, in the palm of my hand that is made up of the same blood of my ancestors, in the transcripts I read from the great Mazatec visionary María Sabina García of Oaxaca.

Sometimes a word can be translated into more than a meaning; in it is a way of looking at the world, and, yes, even a way of accepting what others might not perceive as beautiful. “Urraca,” for example, instead of “grackle.” Two ways of looking at a black bird. One sings, the other cackles. Or “tocayo/a,” your name twin, and, therefore, your friend. Or the beautiful “estrenar,” which means to wear something for the first time. There is no word in English for the thrill and pride of wearing something new.

Spanish gives me a way of looking at myself and the world in a new way. For those of us living between worlds, our job in the universe is to help others see with more than their eyes during this period of chaotic transition. Our work as bicultural citizens is to help others to become visionary, to help us all to examine our dilemmas in multiple ways and arrive at creative solutions—otherwise we all will perish.

When you see a skeleton, what does it mean to you? Anatomy? Satan worship? Heavy-metal music? Halloween? Or maybe it means—Death, you are a part of me, I recognize you, I include you in my life, I even thumb my nose at you. Today on Day of the Dead, I honor and remember my antepasados, those who have died and gone on before me.

I think of those two brave women in Amarillo* who lost their jobs for speaking Spanish, and I wonder at the fear in their employer. Did she think they were talking about her? Didn’t she understand that speaking another language is another way of seeing, a way of being at home with one another, of saying to your listener, “I know you, I honor you. You are my sister, my brother, my mother, my father, my family.” If she had learned Spanish—or any other language—she would have been admitting, “I love and respect you, and I love to address you in the language of those you love.”

This Day of the Dead I make an offering, una ofrenda, to honor my father’s life and to honor all immigrants everywhere who come to a new country filled with great hope and fear, dragging their beloved homeland with them in their language. My father appears to me now in the things that are most alive, that speak to me or attempt to speak to me through their beauty, tenderness, and love. A bowl of oranges on my kitchen table. The sharp scent of a can filled with xempoaxóchitl, marigold flowers, for Day of the Dead. The opening notes of the Agustín Lara bolero “Farolito.” A night sky filled with moist stars. “Mi’ja,” they call out to me, and my heart floods with joy.

Holding a photograph of my father in a San Antonio Day of the Dead procession

* In 1997 in Amarillo, Texas, a small insurance agency hired two women clerks who were bilingual in English and Spanish to deal with their Spanish-speaking clients. Their employer became paranoid when they spoke Spanish to each other and asked them to sign an English-only pledge, which they refused to do. They were fired. The two women felt insulted, while their boss felt they were “whispering to each other behind our backs.”