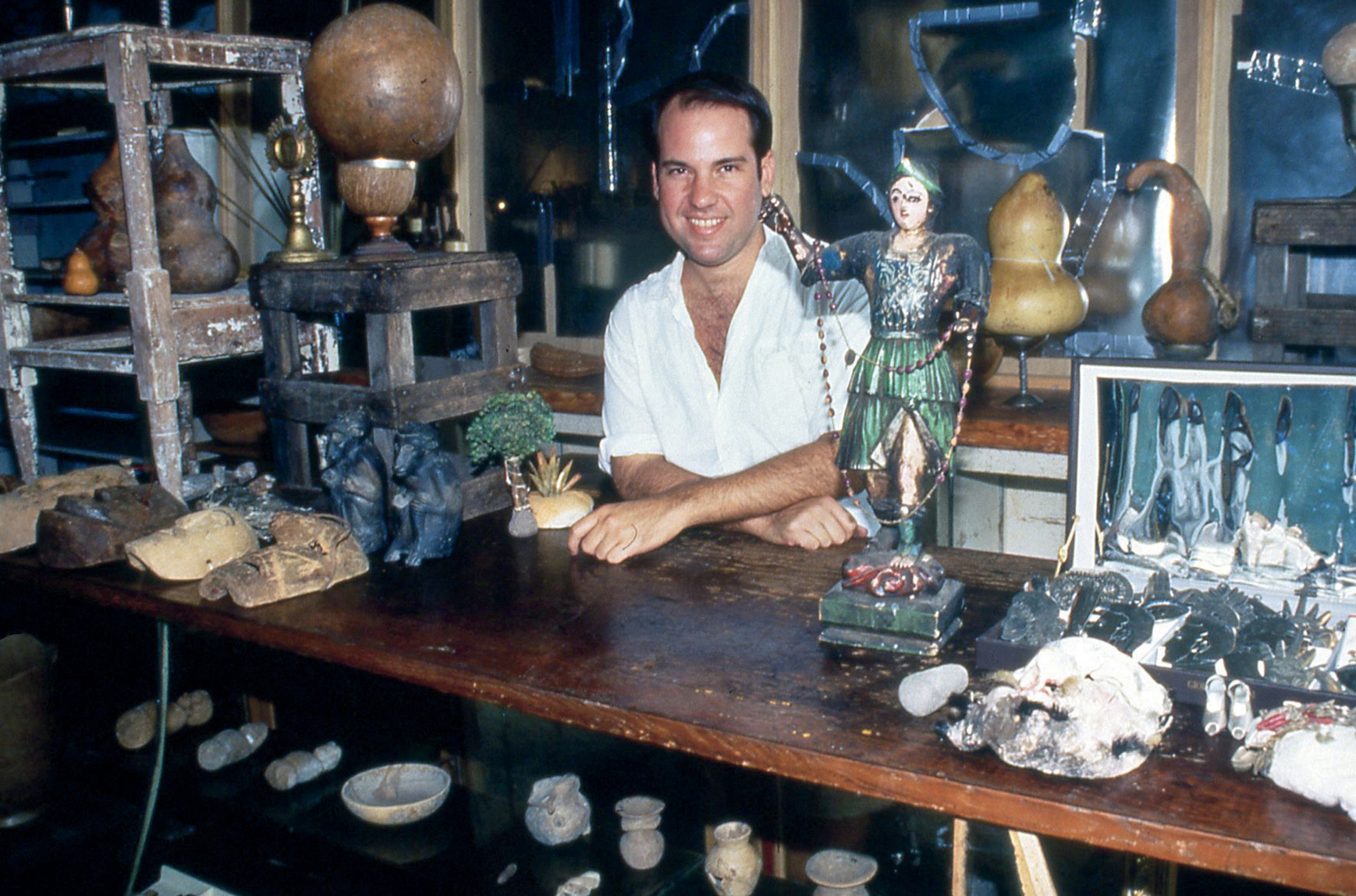

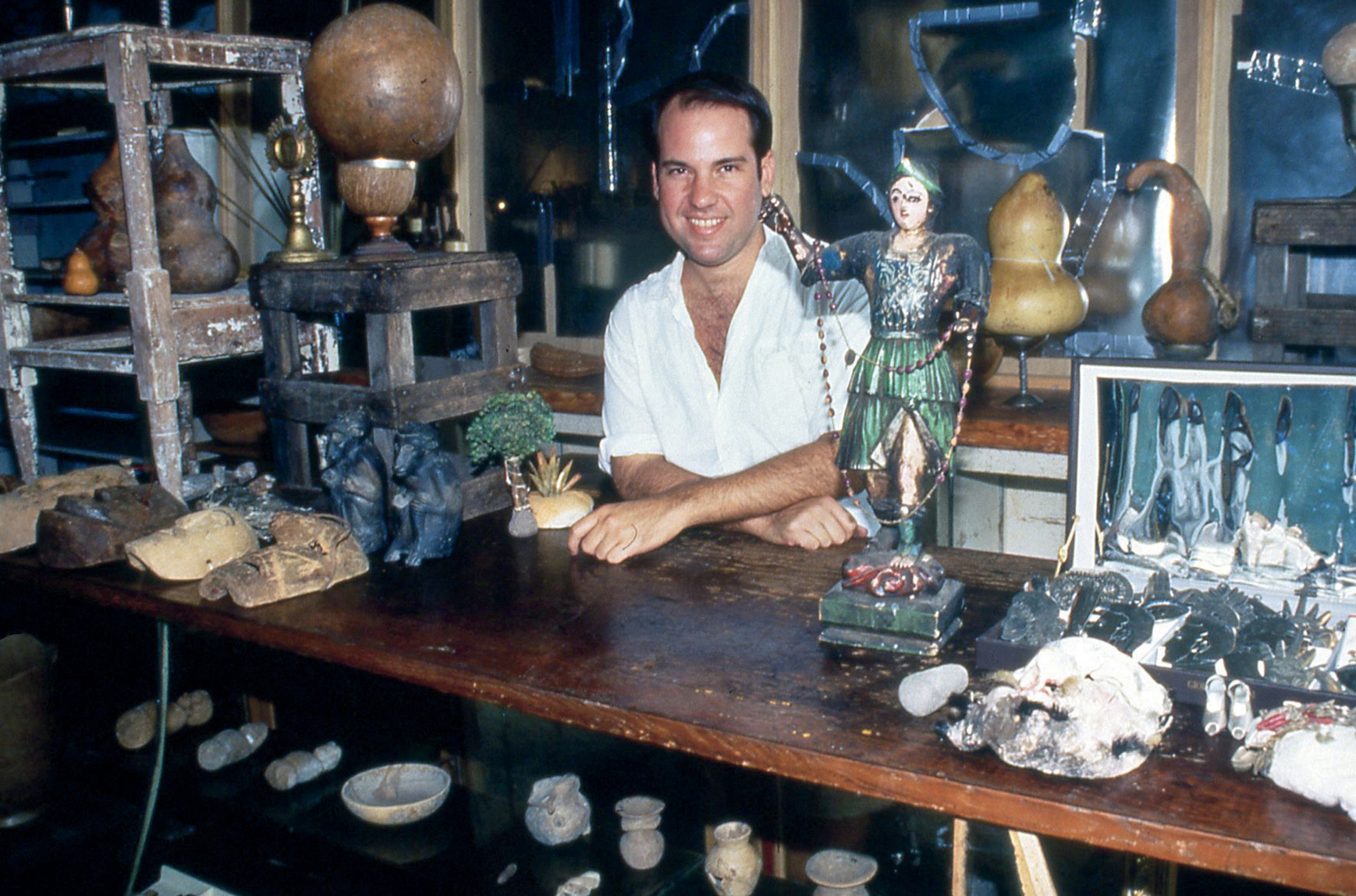

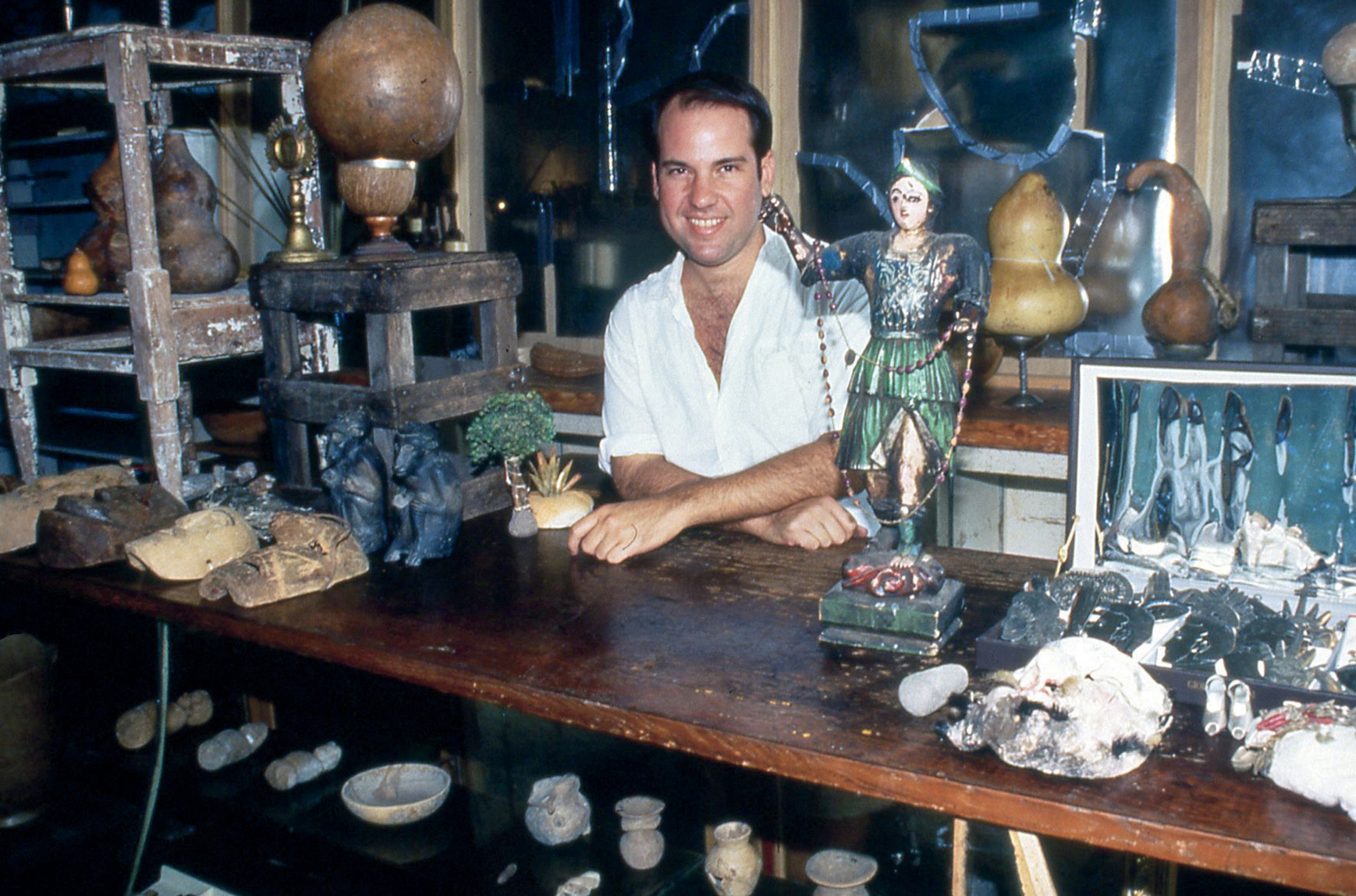

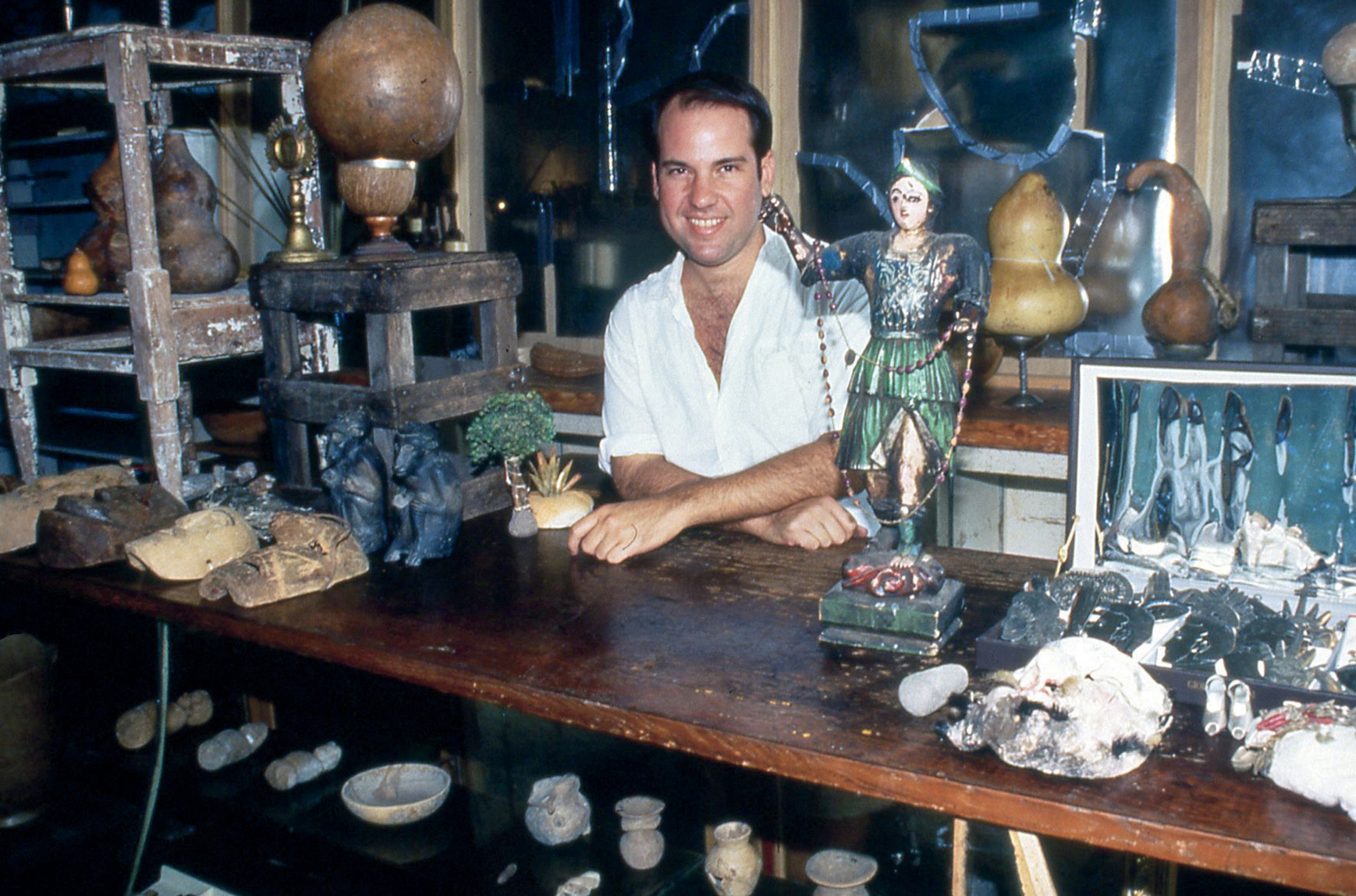

Franco at his glorious botánica

There are so many stories about Franco Mondini-Ruiz. Some he invented himself, and some we were lucky enough to have witnessed, and some became San Antonio legend. Franco is part artist, part eccentric, part genius, part clown, part demon. Sometimes all at the same time. When his collection of sculptures and stories were featured in book form, High Pink: Tex-Mex Fairy Tales, he asked to include a poem I’d written for him years before. But I asked if I could write the introduction, too. I was grateful; Franco, and before him Danny López Lozano, were part of an arts scene in San Antonio that made me feel, finally, at home. Their art happenings in the ’90s were revolutionary gatherings, terrifically inclusive, and brought down the apartheid walls of class, color, and sexuality existent in San Antonio for generations. By the time I finished this introduction, on September 11, 2004, the party was definitely over.

Amor, dinero, y salud, y el tiempo para gozarlos.

(Love, money, and health, and the time to enjoy them.)

—Mexican dicho painted on the side of Infinito Botánica’s building, South Flores Street, San Antonio, Texas

I first met Franco Mondini-Ruiz in the kitchen of his Geneseo Street house. He was living the life of a successful lawyer then. I had my hands in sudsy water and was furiously washing dishes the moment he poked his head through the kitchen doorway and introduced himself. His houseguest had invited us over for an impromptu party, and I remember our panic trying to get the house clean again before Franco walked in from an out-of-town trip.

There was no need to worry, I’d later find out. Franco’s house was always full of strangers. He never locked the doors. Often beautiful boys fell asleep there, and more often beautiful boys ripped him off. He lived like an Italian movie: part Fellini, part Pasolini. This was part of el mundo Mondini, a chapter of my life that was to run its course during the decade of the ’90s.

Falling into Franco’s life was like falling down Alice in Wonderland’s rabbit hole. The house on Geneseo was famous for parties where wealthy little old ladies in gold lamé might appear, as well as six-foot-tall transvestites and a parade of live chickens.

But Franco’s most remarkable feat would be the alchemy of Infinito Botánica, a crumbling Mexican magic shop filled with folk medicine as well as high art. It was the only place in the city where a working-class person might hobnob with a millionaire. Rich Houston ladies shopped alongside tatooed vatos, big Botero-esque babes from the south-side dyke bars, Mexican nationals dressed in impeccable designer wear, and Mexican illegals sweaty from hard labor, the neighborhood Catholic priest. Everyone was welcome. In a sense, it was like one of Franco’s parties, high low, or high rascuache.*

The predecessor of this high-camp living was a man who had inspired us all and introduced us to each other. Danny López Lozano of Tienda Guadalupe Folk Art. It was Danny who provoked a generation of Chicano artists to relook at the bueno, bonito, y rascuache of San Antonio and transform it into glamour. The gatherings at his shop on South Alamo Street, as well as at his parties at his home, became our salon. If anyone was our mother, it was Danny, and we belonged devotedly to the House of Guadalupe.

Franco at his glorious botánica

When Danny died of throat cancer in 1992, it was up to others to carry the torch. Franco stepped in with Infinito Botánica, on South Flores Street. Other artists followed, living upstairs or next door, so that when an arts event occurred, it involved several open studios and the space between. Anything could happen and often did. Performances on the sidewalk spilling onto the street. Backyard cookouts featuring feasts more magnificent than Moctezuma’s. A spontaneous eruption of Pancho Villa moustaches painted on the women and Frida eyebrows on the men.

Some of us aren’t speaking to each other anymore, but for a time not only were we speaking, we were singing arias. Whatever inspired one of us was sure to inspire us all. An outbreak of Buddha art. Day of the Dead altars. Maria Callas look-alike nights. Paquita la del Barrio. Oh, honey, do I have to tell you?

Franco taught us to play. At the Liberty Bar, the name wasn’t just a name, it was a way of life. We might compete for the same boys: “You can have him after me.” A fight might break out over mole—from a jar versus from scratch. But we did see the world through the same rose-tinted glasses called Mexican nostalgia.

Franco taught me to see beauty in pink cupcakes, plastic champagne cups filled with colored water, Mexican pan dulce adorned with pre-Columbian artifacts. I still have the Marie Antoinette living room set I bought at Infinito, full of woodworms and horsehair stuffing, chairs so uncomfortable they’re not for sitting.

That was then. Before 9/11. Before we started getting harassed for looking like the Arab Jews we are. We were escape artists in our escapades, looking for a shortcut to Berlin or Buenos Aires, trying to make high glam from whatever we had on hand. Those times. As a drunk woman so aptly put it at the final Infinito party, “It’s the end of an error.”

* “High rascuache” comes from the brilliant imagination of the art critic Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, who coined the phrase to name objects that are at once funky and glamorous, like a plaster Virgen de Guadalupe statue covered in Swarovski crystals.