My nose is the one on the left.

My friends are highly competitive. After I’d written an intro for the artist Franco Mondini-Ruiz’s book High Pink: Tex-Mex Fairy Tales, Rolando Briseño asked if I’d write something for his upcoming art book Moctezuma’s Table, which would feature his paintings about food. I’m not a writer who can write on assignment, but I said I’d give it a try. It’s a tricky business; when a friend asks you to write about them, it’s like asking you to create their portrait. I warned Rolando, “It might not be a pretty picture.”

Moctezuma’s Table: Rolando Briseño’s Mexican and Chicano Tablescapes was published by Texas A&M University Press in 2010.

It was the night Astrid Hadad sang at the Guadalupe Theater in San Antonio. She had a spectacular show, complete with bandoliers across her corseted chichis, papier-mâché pyramids and cacti, sequined skirts, a holster, pistols that fired blanks, and jokes that hit their targets on both sides of the border. Well, she was the best thing to ride into San Antonio in a long time. We still talk about that night even now though it was years ago.

Astrid Hadad is a Mexican-Lebanese performance artist from el D.F. (Mexico City). She and I once had our photo taken nariz a nariz, because with her Lebanese profile and my Aztec/Arab one, we could be twins, I’m not lying.

My nose is the one on the left.

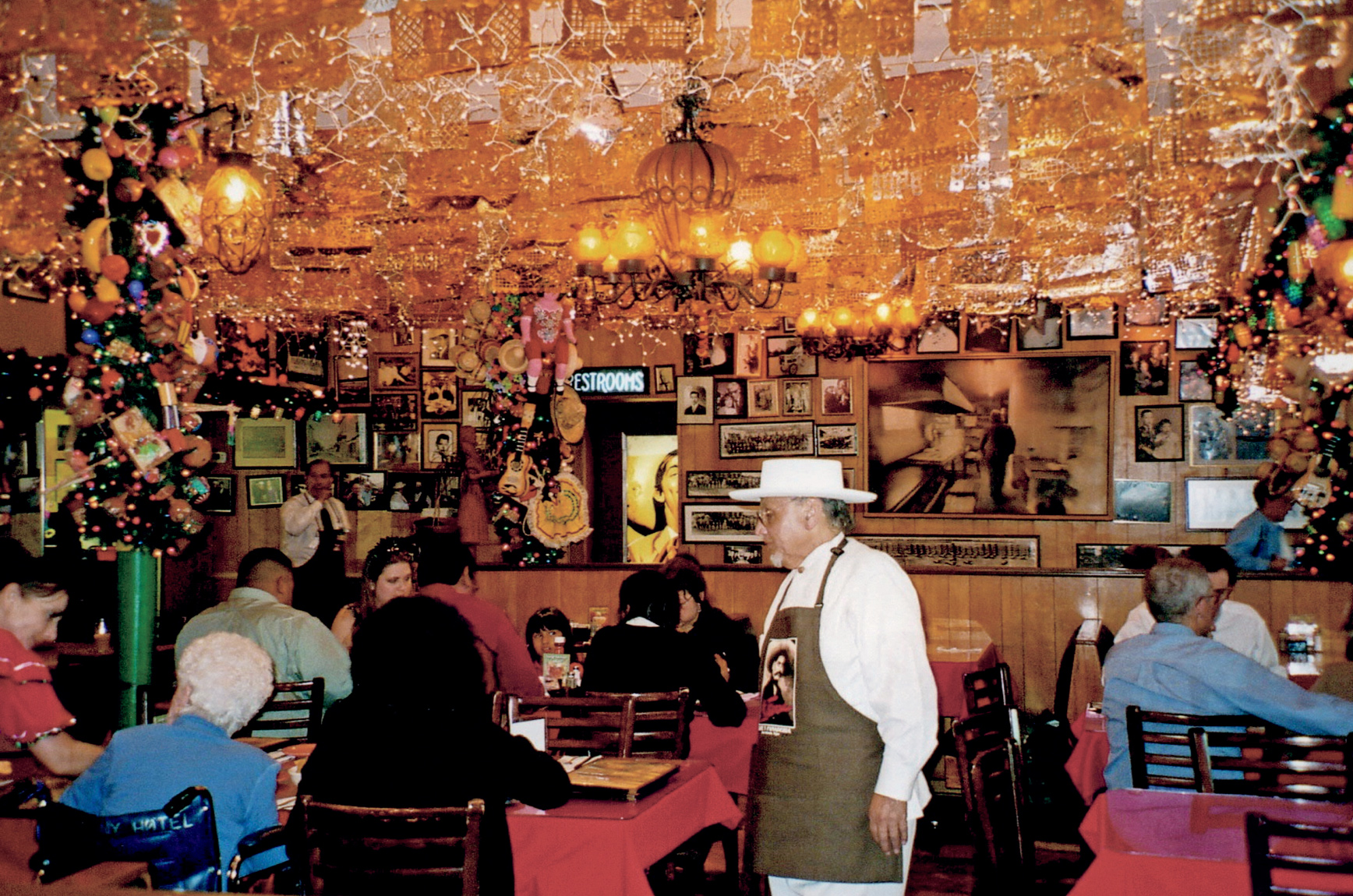

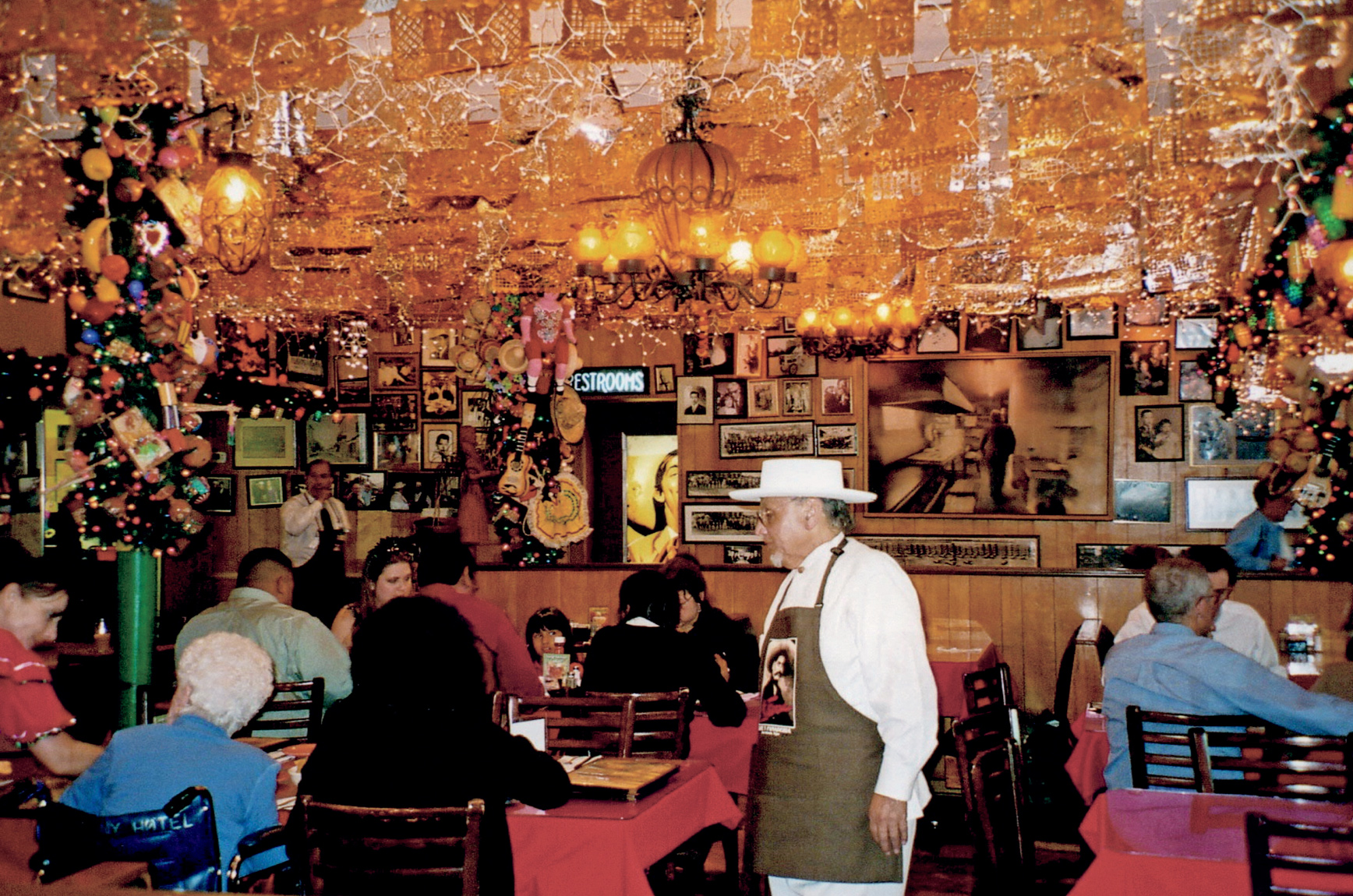

After her show, we invited Astrid to the only twenty-four-hour restaurant we’re not ashamed of, Mi Tierra. With its sugary trays of pan dulce and Mexican candy, enough twinkling lights to illuminate a city, papel picado flags fluttering overhead, strolling músicos, and a room where it’s Christmas all year round, it’s as campy as Astrid.

It was in the shimmering Christmas Room where they seated our party. The table was longer than the Last Supper, with the lucky ones at the center next to Astrid, and the ones who got there early and weren’t thinking seated at the no-man’s-land at the end, like Judas. We were the tontos seated at the end.

Now, you have to know this was when Astrid was really famous. Maybe you haven’t heard of her, but anyone who lives in Mexico or watches Mexican television would know that nose anywhere. She had risen from singing her political feminista numbers in cafés and bars, where I first saw her, to appearing in a popular telenovela. I wish I could tell you the name, but to tell the truth I never knew it. So this happened when she was on television, and Astrid Hadad was on everyone’s tongue, from the mex-intelligentsia to the pobre who offered to wash your windows at the stoplight.

Mi Tierra Restaurant, the Christmas Room

I don’t know why everyone wants to go to dinner with a famosa, because you never get to talk to the guest of honor, and even if you do, she’s tired after a show where she’s been belting them out, and to make matters worse, that night she was coming down with something. “My throat hurts,” Astrid said, reaching into her purse and bringing out her own medicine, a tequila she swore she never traveled without. And again I wish I could tell you the name, but you know how I am. Unless I write it down, forget it.

It was time finally to order dinner. The waiter was having a hell of a time with so many folks seated at such a long table, and with a woman who looked like a cross between Cleopatra and Vampira slugging back tequila from her own botella, well, imagine.

Rolando Briseño to my right, Ito Romo to his right, and my best friend, Josie Garza, on his right

Then it was our turn to be humble and act like groupies, after that show where she knocked us out with songs like “Un Calcetín” and “Mala,” we were ready to genuflect right then and there and kiss her red high heels with the spurs. And to make matters even better, she was whip-smart and well read, a woman of tremendous intelligence, not the vapid vedettes of Mexican television.

So we’re at Mi Tierra restaurant in el Mercado, right? It’s probably just past midnight, the beginning of the evening for me, but in sleepy, pueblerino San Antonio, the middle of the night. We’re here because this is one of the few spots open, and because they serve drinks, and even though the place is flooded with tourists in the day, after midnight the locals pile in for a bowl of menudo for their cruda, or pan dulce and Mexican hot chocolate after a velorio, or to slurp up a big bowl of tortilla soup after a night out, and I mean big, even bigger than your head.

Here we are, then, the writer/artist Ito Romo, the visual artist Rolando Briseño, and me, and I don’t know who else besides Astrid and her musicians, but the table is filled with a whole lot of hangers-on hanging on. I remember Ito decides to order enchiladas de mole, and that’s where the whole pleito begins.

More or less the conversation that night, the way I remember it:

ROLANDO: [in an incredulous tone, as if he were about to bite into cat caquita] You’re going to order enchiladas…de mole! Here? You wouldn’t catch me ordering mole. Forget it, I bet they make it from a jar. You could never get me to eat them in a million years. In my house we grew up with my mother making mole FROM SCRAAATCH. [This last part was with an accompanying Jackie Gleason hand gesture and leer.]

ITO: A poco. [And here he starts to laugh in a typical Ito risa, with his shoulders hunched like a vampire, and a giggle rising out of him like a gurgling fountain overflowing.] What a liar you are, Rolando! Your mother made jar mole from Doña María like everyone else’s mother from here to Torreón.

ROLANDO: My mother made mole FROM SCRAAATCH. Not from a jar. I can’t BELIEVE your family would eat mole from a jar!

ITO: Aw, come on. You’re trying to say your mother dried the chiles, and ground them up, and took days and days to make mole from scratch? You’ve got to be kidding! Who do you think we are to believe such a story?

ROLANDO: My mother would never THINK of making mole from a jar. What are you TALKING about!

ITO: Rolando, how do you have the nerve to say such things. She NEVER made mole from a jar?

ROLANDO: Never.

And like that and like that. So that the way it ended, they were furious with each other before the enchiladas even arrived, and they haven’t talked to each other decently since, even though that was the same night Astrid belted out a song for dessert that had everyone, including the kitchen help, flooding the Christmas Room with applause.

But that was a long time ago. Over a decade, to be precise. I recently invited myself to mole dinner at Rolando’s house. This was because I had fresh mole that padrinos from Mexico City had brought in a cooler in their car, a mole dark and moist like a heart freshly sacrificed in an Aztec ritual. And besides, everyone knows I don’t cook.

It was a splendid dinner, with several courses beautifully presented. Beneath an elegant chandelier, the table shimmered with Rolando’s grandmother’s century-old china and fiftieth wedding anniversary silver.

But when the main course arrived, it was green mole Rolando finally decided to serve, not the red mole that had traveled all the way from Mexico City.

“Wow!” I oohed and aahed. “And how long did it take to prepare the mole?” I asked.

“Oh, it was easy,” he said, brushing the air with his hand. “I made it from a jar.”

PILÓN/BONUS TIDBIT

Though I admit to having reconstructed dialogue, this story is true. There are witnesses to back up my claim. Rolando, however, insists my account is nothing but puro cuento, pure story. But that, dear reader, is another pleito.