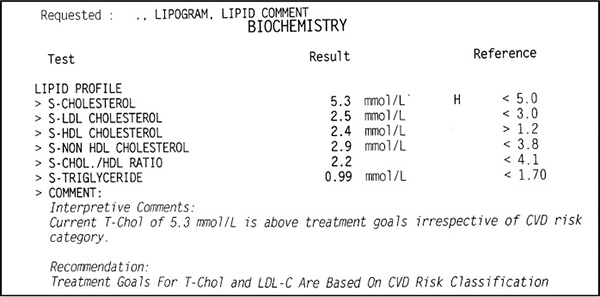

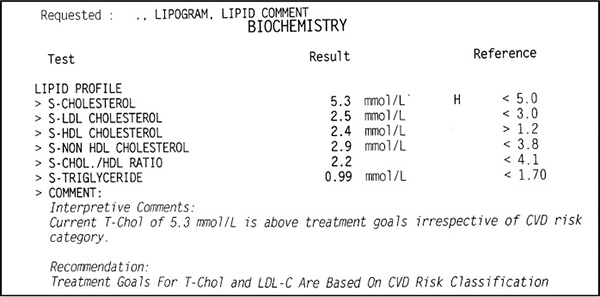

Figure 1. Example of a standard lipogram test result

One of the questions we are most frequently asked is,‘Can I do this diet if I have XYZ ailment?’ We will discuss the most common of these conditions below, but it is important to remember that, firstly, this is not a one-size-fits-all programme – the diet should be adapted to the individual. Secondly, there is nothing detrimental about eating a diet rich in fresh whole foods.

In this section we discuss common illnesses that may, in fact, be corrected or assisted by eating an LCHF diet. There is a global epidemic of ill health and it is largely a result of poor diet. We really are what we eat! Conditions like type 2 diabetes and obesity have a massive impact on the economy. People are sicker and unable to work long hours, so they are less productive. And they drain government health-care funds.

Every day we see people suffering from a multitude of illnesses – including poor cholesterol, sleep apnoea, irritable bowel syndrome, fatigue, swollen legs and yeast infections. They struggle with blood sugar levels, food cravings and constant hunger.

The good news is that these health issues are largely, if not completely, reversible. Many are self-inflicted, which means it is up to the individual to undo them. So often we’re told by health-care practitioners that such-and-such disease is chronic and that we need to be on medication that reduces the symptoms but does nothing to address the underlying cause. And medication often comes with nasty side effects that further hamper quality of life.

Between us we have experienced the effects of obesity, prediabetes and inflammatory joint pain. We have experienced the yo-yoing blood sugar levels, the hunger and the fatigue. We understand the inconvenience of having to check blood sugar and having to eat half a dozen times a day to keep it stable. We understand the dependence on medication to dull pain in order to get through the day. We also understand the fear that comes with having a potentially chronic illness and the consequences of a devastating disease. But we have also experienced how liberating it can be to take back one’s health with dietary changes. We are not offering a miracle cure, but we would like to show you how eating correctly can improve many conditions and possibly even reverse them. We aim to give you a message of hope.

MEDICAL DISCLAIMER

All information is intended for your general knowledge only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment of specific medical conditions.

Your health-care provider should be consulted promptly for any specific health issues.

The information in this section is a summary only and intended to provide broad consumer understanding and knowledge of the discussed health issues.

The information should not be considered complete and should not be used in place of a consultation with your doctor or other health-care provider.

We neither recommend the self-management of health problems nor do we recommend you disregard the advice of your physician.

Do not delay seeking professional medical advice because of something you have read here.

We recommend you select a physician who is knowledgeable and supportive of the LCHF way of eating.

If you suffer from any of the following conditions, it is always best to consult your health-care practitioner before embarking on any new diet.

You may be familiar with the term ‘metabolic syndrome’, or ‘syndrome x’ as it is otherwise known. Metabolic syndrome is not really a disease. It is a group of risk factors that includes high blood pressure, high blood sugar (insulin resistance), unhealthy cholesterol levels and abdominal fat. Having even one of these health problems is not good, but when combined they double your risk of cardiovascular disease and increase your risk of developing diabetes fivefold. The complications that may result from this syndrome include heart attack, stroke, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, kidney disease and diabetes. The good news is that metabolic syndrome can be controlled, largely through changes to lifestyle and primarily diet.

One of the most common questions we get asked is, ‘Is the LCHF diet safe for someone with diabetes?’

The simple answer is a resounding yes; not only is it safe, it is potentially lifesaving.

Let’s examine diabetes a little more closely and discuss how an LCHF diet may help improve and possibly even reverse it. We cannot overemphasise the role of diet in controlling diabetes. The current dietary guidelines given to many diabetics not only exacerbate their disease, but place them on a road to chronic ill health. One information brochure distributed by a registered dietitian stated that ‘patients can have sweets prescribed by registered dietitians in a safe, practical way that fits into your insulin regime’. This is terrible advice.

What exactly is diabetes? Many diabetics have a poor understanding of their disease. They are simply told that their sugar levels are too high and are medicated accordingly. They seem to have little or no understanding that the foods they eat influence the progression or cessation of their disease. First off, we need to differentiate between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. In general, type 1 and type 2 are opposites. Type 1 is characterised by a severe shortage of insulin, while type 2 is characterised by a severe excess of insulin. To understand diabetes, we therefore first need to have a look at insulin and its role in the body.

Insulin is a hormone that is important for metabolism and the utilisation of energy from ingested nutrients, especially carbohydrates. It is made in significant quantities in the beta cells found in the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas.

The body breaks down or converts most carbohydrates into sugar glucose, which is then absorbed into the bloodstream. Insulin plays a number of roles in the body’s metabolism, including increasing the fat-cell uptake of fatty acids from the blood. Primarily, insulin causes cells in the liver, muscles and fat tissue to take up glucose from the bloodstream and convert it to glycogen. Glycogen can then be stored in the liver and muscles and used at a later time for energy.

Insulin is secreted primarily in response to raised concentrations of glucose in the blood, thereby regulating blood glucose levels in the body. Other stimuli, like the sight and taste of food, nerve stimulation and increased blood concentrations of other fuel molecules, including amino acids and fatty acids, also promote insulin secretion.

Without insulin, or with cells resistant to the effects of insulin, the body cannot take glucose from the blood, causing a rise in blood glucose levels in the blood and leading to the condition known as diabetes mellitus.

High levels of blood glucose can contribute to damage of the tiny blood vessels in your kidneys, heart, eyes and nervous system. That’s why diabetes, especially if uncontrolled, can cause cardiovascular disease, kidney damage and failure, blindness, and damage to nerves in the hands and feet.

Type 1 diabetes, sometimes known as juvenile diabetes or insulin-dependent diabetes, is a lifelong (chronic) condition in which the pancreas produces insufficient or no insulin. Although type 1 usually appears during childhood or adolescence, it can also begin in adults. When diagnosed later in life, it is referred to as latent autoimmune diabetes of adults (LADA).

With type 1 diabetes, the body’s immune system attacks part of its own pancreas. The immune system mistakenly sees the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas as foreign, and destroys them. This ‘attack’ is what is known as an autoimmune disease.

The exact cause of type 1 is unknown. Genetics may play a role, and exposure to certain environmental factors, such as viruses, may trigger the disease.

Type 1 diabetes has no cure, but it can be managed. People with type 1 depend on external insulin (most commonly injected through the skin) for their survival. Without insulin, type 1 diabetes is fatal. With proper treatment and correct diet, people with type 1 can expect to live long and healthy lives.

In the past (and even today), a high-carb, low-fat diet was the standard dietary recommendation for type 1 diabetics. Because a lot of type 1 sufferers eventually develop heart disease, it became common practice to recommend the low-fat ‘heart-healthy’ diet. It was (and in some circles still is) believed that a diet rich in fat would clog the arteries and cause heart attacks. In order to prevent this, diabetics were advised to remove all fat from their diet and eat a diet of predominantly carbohydrates. A high-carb diet meant that more insulin had to be injected to control blood glucose, but that wasn’t considered a bad thing.

Now we know that saturated fat is not the problem child it was once believed to be. In a review published in early 2015, researchers found no evidence from randomised controlled trials to support the low-fat diet introduced with the dietary fat guidelines in the late 1970s.1 On 8 May 2015, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics in America, commenting officially on the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, recommended dropping saturated fat from the guidelines due to the lack of evidence connecting it with cardiovascular disease.

So, cutting out saturated fats and replacing them with carbohydrates was a mistake, but you may still wonder why carbohydrates are a problem. Previously, it was assumed that high doses of insulin are not harmful to the body. We now know that this is not true and that high levels of insulin over a long period will lead to insulin resistance.

Studies to determine causes of mortality in type 1 diabetics have found that people with type 1 have a four times higher risk of dying earlier than non-diabetics and that, contrary to popular belief, glucotoxicity (toxic levels of glucose in the blood) is not the primary cause. The Eurodiab study2 showed that although glucotoxicity did have a small effect on mortality, this effect was much lower than the risk associated with waist-to-hip ratio, which is used to measure visceral fat. For those unfamiliar with the term, visceral fat is body fat that is stored within the abdominal cavity around a number of important internal organs such as the liver, pancreas and intestines. This is interesting because increased visceral fat is usually found in people with metabolic syndrome where insulin is in excess. This is typical of type 2 diabetes, not type 1. So why is this happening in people who have too little insulin? Type 1 diabetics who eat a high-carbohydrate diet require large amounts of injected insulin. These repeated high doses of insulin result in insulin resistance and visceral fat storage.

Studies3 of diabetics who have successfully managed their disease for 50 years or more have shown that some have survived despite their blood sugar levels being not well controlled. In some cases life expectancy increased when blood glucose levels were kept low, but in other cases not. How did they beat the odds?

One study states that ‘one of the major factors linked with long-term survival is the absence of features of the metabolic syndrome and more specifically the presence of insulin sensitivity’.4 In other words, long-term survival depended on the type 1 diabetic not developing insulin resistance, and the best way to achieve that is to keep insulin demand low.

Eating a high-carb diet increases insulin demand and leads to the development of insulin resistance. When type 1 diabetics develop insulin resistance, they are actually developing type 2 diabetes. They now have double diabetes. Following a high-carb diet if you’re type 1 is, therefore, a recipe for disaster.

In a 2012 study, a low-carb diet was tested on a group of type 1 diabetics. Subjects had to limit their carbohydrate intake to no more than 75 grams per day. Blood sugar was assessed with a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) test, which gives a measure of average blood glucose over a period of two to three months. At the start of the study, the average HbA1c of the subjects was 7.6 per cent (the ideal for non-diabetics is around 5 per cent). They were re-tested after three months and again after four years. Subjects who did not comply with the carb restriction saw no change in their blood glucose average. Those who did saw a significant drop to an average of 6 per cent.5 Insulin requirements decreased in the diet-compliant individuals and their dosage was adjusted downwards accordingly. This is a clear example of vastly improved blood glucose control and reduced need for medication on a low-carbohydrate diet.

In another study,6 61 adults with type 1 diabetes treated with CSII (insulin pump) were randomly assigned either to learning carbohydrate counting (intervention) or estimating pre-meal insulin dose in the usual empirical way (control). The study concluded that carbohydrate counting is safe and improves quality of life, reduces body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference, and reduces HbA1c.

Type 1 diabetics need to be aware of both glucotoxicity and insulin toxicity. It therefore makes sense to follow a diet comprising foods with a lower insulin requirement rather than to liberally eat carbohydrates that require industrial doses of insulin to manage the glucose tsunami delivered from the gut.

Type 1 diabetics will always require exogenous insulin, but it would be prudent to follow an LCHF diet to minimise insulin toxicity. Furthermore, injectable insulin does not act as quickly as the body’s natural insulin, and there will always be a margin of error when calculating insulin requirements to counteract the quantity of carbohydrates consumed.

For type 1 diabetics who would like detailed information on following a low-carb diet, we recommend Dr Richard Bernstein’s YouTube channel7 where he presents a series of video talks for diabetics. Bernstein was diagnosed with type 1 at the age of 12. For two decades he followed doctors’ orders and experienced deteriorating health. He then began tracking his blood glucose levels in response to different foods and soon realised that carbohydrates were sending his levels on a roller-coaster ride. At 45, Bernstein enrolled to study medicine and, in 1983, opened his own practice in which he advocates a low-carb diet for both his type 1 and type 2 patients. He has also published a book, Dr Bernstein’s Diabetes Solution.8

IMPORTANT TO NOTE

For insulin-dependent diabetics it is imperative to discuss any dietary changes with your medical practitioner and get assistance with calculating or changing your required doses of insulin.

By far the most common form of diabetes is type 2 diabetes, which accounts for 95 per cent of diabetes cases in adults. It was previously known as non-insulin-dependent or adult-onset diabetes, but with the epidemic of obesity among children, more teenagers are now developing type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes is always serious. If it is left untreated or is not well managed, the high levels of blood glucose will slowly damage both the fine nerves and the blood vessels, resulting in a variety of complications. Even a mildly raised glucose level that doesn’t cause any symptoms can have long-term damaging effects. Complications develop gradually, and can eventually be disabling or even life-threatening. Some of the potential complications of diabetes include:

Diabetes associations tell us that with careful management, these complications can be delayed and even prevented, but seldom is a diabetic told that his or her disease may be reversed.

While many diabetics are told that their disease is chronic and progressive, type 2 diabetes is a dietary disease that is preventable and largely reversible. Although there is an inherited predisposition to developing type 2, which means if one or more of your parents have it, you have a higher chance of developing it, the disease is preventable by following the correct diet.

Let’s be honest, we eat fast food, processed food and refined carbohydrates all packed with sugar, artificial preservatives, flavourants and chemicals and yet we expect to stay well. This disease is caused by the foods we eat – nothing else. And in most cases it can be reversed by changing those foods and modifying our lifestyle.

Although medication is often prescribed, type 2 diabetes cannot be effectively treated with drugs. Standard treatment is to begin with a drug like metformin to increase cell sensitivity to insulin. As the patient becomes increasingly insulin resistant, given that there has been no change in diet, medication is increased to include a group of drugs known as sulfonylureas, which squeeze the last of the insulin from the already exhausted beta cells in the pancreas. With still no appropriate change in diet, the diabetes worsens, there is a consistent increase in blood glucose levels, and insulin is prescribed. The diabetes has not in any way been improved by the drugs. In fact, it has worsened. If diet does not change, all we will see is further deterioration in health and a concomitant increase in insulin dosage.

A study of 67 981 diabetic patients from 2000 to 20069 revealed a substantial increase in the prescription rate of anti-diabetic medications. But medication is treating the symptoms, not the cause. And the underlying cause of type 2 diabetes is the body’s resistance to high levels of insulin created by a diet high in refined carbohydrates, sugar and fructose. High blood sugar is therefore a symptom of diabetes, not the cause.

Dr Jason Fung, a Canadian nephrologist and a speaker at the first LCHF Conference, in Cape Town in 2015, has a great video talk on YouTube titled ‘The Two Big Lies of Type 2 Diabetes’ in which he explains how we develop type 2 diabetes, why current dietary treatments and drugs are ineffective in treating the disease, and how to reverse it. He also presents a number of patient case studies. We recommend that all type 2 diabetics watch Dr Fung’s enlightening talks.10

In order to understand how to reverse type 2 diabetes, we need to look at how it develops in the first place. Contrary to what many believe, type 2 diabetes is a disease of too much insulin. We’ve already looked at insulin, so now let’s look at insulin resistance.

Insulin resistance occurs when our cells are exposed to too much insulin for too long. The human body was not made to be loaded with glucose. At any one time, the body can only metabolise about 4 grams of glucose (one teaspoon), yet our Western diets are packed with glucose. Aside from the added sugars found in processed foods and soft drinks, many of the ‘normal’ foods we eat convert to glucose in the body. Potatoes, bread, rice and pasta – these all convert to glucose. One cup of cooked spaghetti contains the equivalent of 10 teaspoons of sugar! Let’s look at a ‘healthy’ option – a slice of low-GI seeded brown bread contains the equivalent of eight teaspoons of sugar! These carbohydrate-rich foods all require large amounts of insulin to metabolise them. Just imagine how much insulin the pancreas is producing a day when we eat a carbohydrate-rich diet.

If our body can only use a teaspoon of glucose at any one time, what is happening to the rest of the glucose we are pouring into it? The glucose has to be removed from the bloodstream, because too much glucose in the blood is damaging; so, under the influence of insulin, the excess glucose is stored as fat.

The more carbohydrates we eat, especially refined carbohydrates, the higher the glucose in our system, the more insulin we need and the harder our pancreas has to work to produce all the insulin we require. On top of tiring out the pancreas, the cells in our body become tired of responding to the high levels of insulin being secreted.

Certain cells in the body, especially those in the liver, muscles and fat tissue, contain what we call insulin receptors. Imagine a door lock and key. The receptors are the lock and insulin is the key. These receptors respond to insulin (the key), opening the cell membrane to allow glucose into the cell. With an endless onslaught of insulin hammering away at the lock, the key no longer fits well and the door does not fully open. We therefore have less glucose entering the cell and the cell in turn signals that it is starved of glucose. As a result, the body produces more insulin (the keys) until the cell is eventually able to get enough glucose.

As we develop resistance, our body increases insulin levels to get the same end result – glucose into the cells. However, this results in ever-increasing levels of insulin. When the cells no longer respond to insulin, blood sugar remains elevated because the cells cannot remove it from the blood. The result? Diabetes.

So, too much insulin causes insulin resistance. The more insulin we produce, the more resistant we become and the more insulin we have to produce. Why on earth, then, do we treat type 2 diabetics with the hormone they already have in abundance and to which they are resistant?

One study to determine whether excellent blood glucose control could be achieved using intensive insulin therapy in the management of type 2 diabetes without the development of unacceptable side effects concluded that large doses of exogenous insulin were required to overcome insulin resistance. This resulted in hyperinsulinaemia (excess levels of insulin in the blood) and significant weight gain.11 In other words, giving the type 2 diabetics insulin actually made their diabetes worse, not better. Why, if high insulin levels are the cause of type 2 diabetes, does conventional treatment aim to lower blood sugar instead of aiming to lower insulin levels?

At the 2015 LCHF Conference in Cape Town, Dr Fung explained that focusing on removing glucose from the bloodstream is a little like cleaning out your kitchen by throwing the rubbish into your lounge. This is what happens when we inject insulin to lower blood sugar. Glucose is removed from the bloodstream and forced back into the body’s tissues. The more our blood sugar rises, the more insulin we require to dump the glucose into the tissues. Under the influence of insulin, excess glucose (rubbish) is converted to fat and stored in the liver. When the liver capacity is exceeded, fat is stored in adipose tissue in the abdomen, hips, breasts and buttocks, among other places. Once these regions are full, fatty acids begin to spill over into organs like the heart and kidneys.

Browsing diabetic websites can be depressing. Diabetes Australia, for example, tells us that ‘over time most people with type 2 diabetes will also need tablets and many will also need insulin. It is important to note that this is just the natural progression of the condition, and taking tablets or insulin as soon as they are required can result in fewer complications in the long-term.’12 But is this true? Diabetics are also usually told that they do not have to follow a special diet. But if carbohydrates raise insulin levels, surely these should be restricted? Furthermore, diabetics are advised to eat regular, low-fat meals, and are encouraged to snack between meals. We know that every time we eat, we secrete insulin. How, then, is eating five times a day helpful to a type 2 diabetic? Surely diabetics should not be advised to eat meals that convert to glucose multiple times a day? Some websites even advise that they can eat sugar as long as they take enough insulin to lower their blood sugar levels. That’s absolutely ludicrous. Even the American Diabetes Association13 website offers some suspect advice. Besides advocating the consumption of starchy foods like whole-grain breads, cereals, pasta and rice, and starchy vegetables like potatoes, yams, peas and corn, the site also states that when ‘combined with exercise, sweets and desserts can be eaten by people with diabetes’.

In 1917, Diabetic Cookery, a recipe book by Rebecca Oppenheimer, listed foods ‘strictly forbidden’.14 These included sugars, all farinaceous foods (pasta, noodles, rice, polenta, gnocchi) and starches, pies, puddings, flour, bread, biscuits and sago. Yet many of today’s recommended diabetic diets contain some of these past forbidden foods. It’s no wonder diabetics are getting sicker.

There are various classes of diabetic drugs that are prescribed depending on the progression and severity of the disease. All are aimed at reducing blood glucose levels. Treatment protocols differ slightly from country to country and not all classes of drugs are used in all countries. At some stage a doctor may decide to combine two or three types of tablets to maintain blood glucose levels. Metformin with a sulfonylurea is a common combination.

In their eagerness to medicate, many doctors completely overlook the importance of limiting the intake of sugar and foods that turn to sugar. Most fail to recognise that high levels of insulin are at least as much of a danger to health as high levels of sugar.

Large studies have shown that reducing blood glucose levels makes no difference to the risk of death. In one study, in which 10 000 subjects were randomised into two groups, namely ‘tightly controlled blood glucose’ and ‘not tightly controlled blood glucose’, the trial was stopped after three years because the subjects in the tightly controlled group were doing worse, showing an increase in risk of death.15 Intensive interventions did not reduce the rates of cardiovascular outcomes as hypothesised. Further studies have shown similar results.16

It is widely accepted that type 2 diabetes is a lifelong, irreversible illness. However, just because something is widely accepted does not mean that it is correct.

According to Dr Fung, ‘Patients often come to our clinic with two “facts” established in their minds. The first is that type 2 diabetes is a chronic and progressive disease. They are often told that they will have the disease for the rest of their lives and they should get used to it. Actually, it is not true at all. Type 2 diabetes is an entirely curable disease. However, taking medications will not cure the disease. Only dietary management has a hope of reversing diabetes.’17

Within days of bariatric surgery (weight-loss surgery) in the majority of people with type 2 diabetes we see a restoration of normal glucose metabolism. According to Dr Roy Taylor, professor of medicine and metabolism at the University of Newcastle, ‘Type 2 diabetes is a potentially reversible metabolic state precipitated by the single cause of chronic excess intraorgan fat.’18 The organs that accumulate fat are the pancreas and liver. Taylor explains that severe calorie restriction is similar in effect to bariatric surgery, and that within a week of surgery or severe calorie restriction, liver fat is significantly reduced. Liver sensitivity returns and blood glucose levels return to normal. Furthermore, within eight weeks of intervention, pancreatic fat content reduces. With this reduction is an associated increased rate of insulin production from the pancreatic beta cells. These are the cells thought to be permanently damaged, remember? Taylor also points out that the greater the fat accumulation in the liver, the less sensitive it becomes to insulin. Whether the subject is obese or not, as circulating levels of insulin increase, so too does fat production in the liver. Type 2 diabetics have an above average liver fat content. Taylor’s findings suggest that in order to restore insulin sensitivity, we need to offload the fat in our livers.

Some have argued that the reversal of diabetes seen in bariatric surgery is due to a complex series of metabolic functions in the gastrointestinal tract caused by the surgery itself. However, studies have demonstrated that normal glucose levels and normal beta cell function can be restored by a very low-calorie diet alone.19 There is now no doubt that type 2 diabetes reversal is possible, that it depends on a sudden and profound decrease in food intake, and does not relate to any direct surgical effect.

Dr Taylor recommends a diet designed to mimic the sudden reduction of calorie intake that occurs after gastric bypass surgery. This basically equates to a restriction of 600 calories per day for a period of eight weeks. A diet like this is not sustainable long term. Furthermore, unless we reduce the insulin load by choosing the right foods, when we come off the severe calorie-restricted diet, chances are high that we will pick up weight and fall back into an unhealthy cycle of eating, insulin spikes and weight gain.

As type 2 diabetes is a disease of too much insulin, treatment should involve reducing insulin. It would, therefore, make sense to restrict or remove from our diet foods with the highest insulin demand, namely carbohydrates.

Numerous studies have shown that refined carbohydrate consumption is associated with health problems, specifically metabolic syndrome. In excess of 20 studies have shown that low-carb diets are more effective than low-fat diets in achieving weight loss, as well as greater improvement in other health markers, including cholesterol, blood pressure and blood sugar.20

Lowering our intake of obvious sugars is clearly beneficial in controlling blood glucose; however, not all carbs are equal. On the one hand, carbohydrates found in whole-food form, like vegetables and whole fruit, are unprocessed and contain natural fibre. On the other hand, refined carbohydrates are stripped of goodness and are usually little more than empty calories providing no nutritional benefit. Furthermore, they are metabolised by the body to produce large amounts of glucose. These include sugar, pastries, bread, pasta, white rice and sugar-sweetened beverages.

Different forms of carbohydrates have different effects on our blood glucose levels and therefore require varying amounts of insulin to metabolise them. The Insulin Index21 is a measure used to quantify the typical insulin response to various foods. This index is based on blood insulin levels, which is really useful because we can see how much insulin our bodies produce in response to specific foods. In order to reverse type 2 diabetes, we need to eat foods with a low insulin index.

An effective low-carb diet will maintain a healthy blood glucose level most of the time. When you avoid eating large quantities of carbohydrates, particularly refined carbs, your blood sugar will improve. With lower blood sugar, your insulin levels will drop too. Reversing diabetes will take some effort and a very low-carb diet may be necessary. It is recommended that diabetics follow a personalised programme with the guidance of a supportive health-care practitioner. For people who are obese or have metabolic syndrome and/or type 2 diabetes, low-carb diets can have life-saving benefits.

A common concern among type 2 diabetics is that they will suffer a ‘sugar low’ if they do not eat six times a day. As we have already seen, eating often is a terrible idea for diabetics, as it drives insulin demand upwards.

If you are diabetic and Banting and you feel that your blood glucose level is dropping, it is important to check it with your glucometer. It is unlikely if you are type 2 and not on medication to increase insulin that your blood sugar will drop below normal, but it is not impossible. If your blood sugar level has dropped, your body should respond naturally and raise it. Unfortunately diabetics have been taught to grab a fizzy drink or a chocolate bar as soon as they feel their blood sugar dip. This is one of the most detrimental pieces of advice that has ever been given to diabetics, especially type 2s.

In adopting an LCHF diet, we are trying to decrease insulin and blood glucose levels. Eliminating carbohydrates that require an insulin response will stabilise blood sugar, and the roller-coaster effect of rising and dropping blood glucose levels should resolve itself.

Often type 2 diabetics will feel as if they are having a sugar low when, in fact, their blood sugar is still well above normal. Why? Ever heard of a ‘false hypo’?

Unless a type 2 diabetic is taking sulfonylureas or injecting insulin, he or she is unlikely to experience genuine hypoglycaemia (glucose deficiency). A false hypo is a feeling of a drop in blood sugar levels. While it may be uncomfortable, it is a well-understood phenomenon and not a crisis. A false hypo can happen when your blood glucose levels are more than 1.5 mmol/l (millimoles per litre) over true normal levels for any period of time (the normal range is between 3.3 and 7.8 mmol/l). Decreasing carbohydrate intake will result in your blood glucose levels dropping closer to the normal range. This drop in blood glucose below values that your body has become accustomed to may result in a feeling of a ‘sugar low’. The body is pretty smart, though, and when it feels a drop in blood glucose to more than about 2 mmol/l below your usual fasting glucose, it secretes what we call counter-regulatory hormones to push your blood sugar back up. That’s right, the body can do this without you grabbing for the nearest chocolate bar or fizzy drink. The alpha cells of the pancreas release glucagon, a hormone that acts on liver cells to increase glucose levels. This response may leave you feeling as if you’ve just narrowly escaped the jaws of death: sweating and heart pounding.

If, for example, your fasting blood glucose is 9 mmol/l and you cut back on carbs, resulting in a blood glucose of 7 mmol/l, your body may well sound the alarm as your blood sugar, for the first time in years, approaches the normal level. It is not easy to sit back and do nothing when you are feeling shaky and faint, but scoffing some high-carb food to ‘fix the problem’ is only going to set you back on your road to achieving a normal blood sugar level.

Once again, if you feel shaky and weak, check your blood sugar level. Unless it’s below the normal range, there’s no need to eat. If, however, you feel that you cannot resist the urge, grab a few nuts or an egg, not an unhealthy sugar-loaded chocolate bar.

Cholesterol is a contentious, much-feared issue. That cholesterol causes heart disease is a lie, and there is a mass of evidence and literature to disprove this myth. Dr Stephen Sinatra, a cardiologist and co-author of The Great Cholesterol Myth,22 says: ‘I don’t believe cholesterol is the villain it’s made out to be when it comes to heart disease. In fact, it’s not much of a risk factor at all.’23

Over the past decade, a tremendous amount has been learnt about the causes of heart disease, but the medical establishment is resistant to change. The notion that high cholesterol is a primary risk factor for heart disease and that a diet high in saturated fat will cause cholesterol problems and heart disease is simply not true.

What is cholesterol, exactly? Cholesterol is a waxy, fat-like substance found in the blood as well as in every cell in the body. Cholesterol plays a vital role – there cannot be life without it! It contributes to the structure of cell walls; without cholesterol, the cells would become flabby and fluid, and we’d look like giant slugs. In many cells, up to half of the cell membrane is made from cholesterol. It also makes up digestive bile acids in the intestines, allows the body to produce vitamin D and enables the body to make certain hormones such as oestrogen, progesterone, testosterone and cortisol. Cholesterol is also vital for neurological function, facilitating cell communication and memory in the brain.

There is no good and bad cholesterol; all cholesterol plays a role. We need to look at the condition of our cholesterol to determine whether there is a problem. The saturated fat and cholesterol we eat has little effect on the cholesterol that is found in our bodies. The liver produces 75 per cent of our cholesterol, while dietary cholesterol makes up only 25 per cent. The body cannot absorb most of the cholesterol found in food. In addition, the body tightly regulates the amount of cholesterol in the blood. If we consume more cholesterol, our body makes less, and when cholesterol in our diet decreases, our body makes more. In fact, studies have shown that eating cholesterol has very little effect on blood cholesterol levels in the majority of people.

Cholesterol is oil based and therefore cannot mix with blood, which is water based, so the cholesterol has to be carried around in vehicles that we call lipoproteins. Think of these lipoproteins as cars, and cholesterol and fat as the passengers.

LDL or low-density lipoprotein, sometimes called ‘bad cholesterol’, transports the cholesterol manufactured by the liver around the body to perform vital functions. HDL or high-density lipoprotein, also known as ‘good cholesterol’, is the friendly scavenger that recycles the LDL by transporting it back to the liver, where it can be reprocessed. HDL could also be called the ‘maintenance crew’, helping to keep the inner walls of the blood vessels clean and healthy. LDL and HDL work together – we need BOTH of them. In reality, cholesterol is far more complex than this. There are subtypes of both HDL and LDL, which makes the idea of calculating a total cholesterol number unreasonable.

Added into the mix are triglycerides, which come from the food we eat and are also transported by lipoproteins. Excess calories in the body are converted to triglycerides and stored as fat. Unlike cholesterol, which is a waxy substance, triglycerides are fat.

You may have heard about lipoprotein(a) or Lp(a). Lp(a) is a lipoprotein subclass, which, because of its small, dense properties, is identified as a risk factor for atherosclerotic diseases such as coronary heart disease and stroke. Lp(a) is often hereditary and is thought to have something to do with coagulation. It can help with wound healing, but at high levels can promote excessive inflammation. This is the particle to look out for in cholesterol testing – it is not part of the standard lipid panel routinely requested by your doctor.

We have established that cholesterol is made by the body and performs vital functions, so where did the hysteria surrounding cholesterol originate?

In 1977, the US government introduced new dietary guidelines that had no scientific basis. Senator George McGovern, who was head of the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, was at the time a great advocate of the Pritikin diet, a low-fat diet based on vegetables, grains and fruits. Helping him to draw up the new guidelines was a chap by the name of Nick Mottern, a vegetarian who had no training in nutritional science.24 In order to justify their new proposed guidelines, McGovern and Mottern turned to Ancel Keys and his Seven Countries Study. Have a look back at Part One for more detail on Keys and his Lipid Hypothesis, which said that eating saturated fat caused a rise in cholesterol in the blood, clogged the arteries and caused heart attacks. There is no evidence that the consumption of saturated fat causes an increase in blood cholesterol levels or cardiovascular disease. It was Keys’s theory that was used by the US government and the expanding vegetable-oil industry to demonise saturated fat and cholesterol and stir up fear of both. Big Pharma jumped on the bandwagon and used the fear of cholesterol to make a fortune from statin drugs. To this day statins are grossly overprescribed.

Cholesterol is not the demon it has been made out to be. But what do we need to know about cholesterol health and what causes it to become a problem?

Some people do have a hereditary problem when it comes to cholesterol. Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) is a genetic disorder characterised by high cholesterol levels, specifically very high levels of LDL, in the blood and can cause early cardiovascular disease. It is estimated that FH affects approximately 1 in 500 people worldwide. However, there are some cultures in which FH is more prevalent, such as the South African Afrikaner population, the Lebanese and the Finns. While a lot of people have elevated cholesterol for any number of reasons, only a fraction have a hereditary problem. This is important to know because many doctors liberally prescribe cholesterol-lowering drugs to people who have no need for them based on the hypothesis that cholesterol is hereditary.

FH is a genetic disorder caused by a defect on chromosome 19. This defect makes the body unable to remove LDL cholesterol from the blood, resulting in high levels of LDL in the blood. Note that people with FH primarily have large, buoyant LDL particles, but they remain at a much higher risk for cardiovascular disease because the concentration of particles is so high. A standard lipogram alone cannot diagnose FH. Only advanced lipid testing or genetic tests can determine whether or not you have the defect associated with this disease.

While a lifestyle change for people with FH is essential, it would be irresponsible to discount sound medical advice and sufferers may need to take medication. For everyone else who does not have FH, an unhealthy lipid profile can be corrected with diet and exercise. Let’s first have a look at what makes cholesterol unhealthy.

Elevated cholesterol may be a symptom of an underlying problem in your body and the cause of this problem is usually inflammation. When we have inflammation in our body, cholesterol is sent to fix it. If the problem is not resolved, the body makes more cholesterol to fight the inflammation. This is why we see a high incidence of unhealthy cholesterol (high LDL) readings in people with metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is caused by persistently high levels of insulin. High levels of insulin cause inflammation in the body, resulting in greater production of LDL particles.25

Another factor that raises LDL levels is the conversion of excess glucose to fat (triglycerides). When we have more fat than we can burn, we see high levels of triglycerides in the blood. LDL particles carry triglycerides as well as fat-soluble vitamins. Remember, LDL is important for cell function and needs to be delivered around the body. The more triglycerides we have taking up space on the lipoprotein, the less room there is for the essential LDL, and the more LDL the liver has to make to ensure the cells get enough of the essential cholesterol that they need. So we see that high triglycerides often go hand in hand with high LDL. There lies the problem. Too many cars on the road can cause accidents, and when particle numbers of LDL are high, there is a greater chance of knocking into an artery wall. This is why it is important to measure particle numbers and not just total cholesterol – but we’ll get to this.

Poor thyroid function is another potential cause for elevated LDL particle numbers. Thyroid hormone plays a complex role in the regulation of lipid production, absorption and metabolism, and also influences the functioning of LDL receptors on cells. With a decrease in thyroid function, the number of receptor cells decreases, leading to reduced uptake of LDL cholesterol by the cells and higher levels of LDL in the blood.

A further cause of elevated LDL is infection. There is some evidence to suggest that lipids increase in an attempt to fight off infection. It is thought that LDL has antimicrobial properties and is directly involved in inactivating pathogens. Other studies suggest that viral and bacterial infections alter the way in which cells metabolise cholesterol.

Now that we have discussed some real causes of unhealthy cholesterol, let’s have a quick look at why a standard lipid test does not tell us much.

The quick finger-prick cholesterol test that you get in your local pharmacy or doctor’s rooms will give a reading of total cholesterol only and is generally useless. As we have seen, there are different lipids that make up cholesterol. Your total cholesterol could be made up of high triglycerides and low HDL (not good) and still be lower than someone with low triglycerides and high HDL (good). So a total cholesterol number does not tell us if there is a problem.

LDL is not measured directly in a standard lipogram. Instead, it is measured using what is known as the Friedewald equation. This equation calculates the concentration of LDL based on the presence of total cholesterol, HDL and triglycerides:

LDL = total cholesterol – HDL – (triglycerides/5)

This equation is widely employed by laboratories and, although fairly accurate, there are certain factors that can cause the LDL value to be incorrect, such as very high triglyceride levels and eating before the blood test.

The trouble with a standard lipogram too is that it does not measure the actual number of lipoproteins in the blood (remember the cars). The measurement is a reading of the total amount of cholesterol that is contained in the HDL and LDL particles. So instead of counting cars, this cholesterol test only counts the passengers in the cars. This does not make sense when it’s the number of cars that increases the risk of accidents.

Another point to keep in mind when looking at cholesterol results is that the results need to be interpreted in the context of overall health. Individual cholesterol numbers by themselves (i.e. total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglycerides) do not predict heart risk. Other factors that need to be taken into account include age, BMI, whether you smoke, and whether you have existing health problems like diabetes and high blood pressure.

Not everyone needs more extensive lipid profiling, but it is important to understand that if you do get results that may be of concern, ask for further testing.

Figure 1. Example of a standard lipogram test result

Figure 1 is an example of a standard lipogram test result for a healthy, normal-weight male with no risk factors. Note that in the interpretive comments we are told that ‘Current T-Chol [total cholesterol] of 5.3 mmol/L is above treatment goals irrespective of CVD [cardiovascular disease] risk category.’ In other words, his cholesterol is too high. This is crazy! If you take a look at the numbers in the result column against the numbers in the reference column you will see that ALL the numbers except the total cholesterol are well within the normal range. It just does not make sense when all these other values look great to tell a person their cholesterol is high. Do you see why a finger-prick cholesterol test is not recommended?

The key to correcting unhealthy cholesterol is to find the cause. As we have seen, a significant factor in unhealthy cholesterol is metabolic syndrome, which is caused primarily by unhealthy eating. Too many refined carbs, too much inflammatory seed oil, and too much sugar and fructose. With insulin resistance being one of the most common causes of raised LDL, it would make sense to follow a diet that decreases insulin levels and to make other healthy lifestyle modifications such as giving up smoking, doing some exercise and getting enough good-quality sleep.

We have given you a fairly simple explanation of cholesterol here to help you understand the basics and hopefully see that cholesterol is not the enemy. To learn more, Bowden and Sinatra’s The Great Cholesterol Myth is a good place to start, and for the science-minded, Dr Peter Attia has a fantastic series of articles titled ‘The straight dope on cholesterol’.26

There is so much hysteria surrounding high cholesterol that you may not be aware that low cholesterol can be really bad for you. Studies have found that, as you age, your chances of an early death increase if your total cholesterol falls. The data from one study showed that after the age of 50, for every 0.026 mmol/l (which is small) drop in total cholesterol per year, the chance of heart death increased by 14 per cent. Can you imagine, then, the increase in risk of reducing cholesterol from 6 mmol/l down to the proposed ‘healthy’ 5 mmol/l?27

And that’s just the start. Another study found that low total cholesterol was associated with characteristics known to predict worse outcomes in heart failure.28 In other words, people who already suffer from heart failure have less chance of survival with lower cholesterol levels.

Low cholesterol has also been linked to increased cancer risk. Cholesterol is a vital building block in cell membranes; it is essential for their integrity and stability. It is possible that normal cell membrane function is impaired with a significant decrease in cholesterol, resulting in loss of resistance to cancerous change.

In a study of 3 282 men and women over the age of 65 by scientists at the Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine at the University of Padua in Italy, ‘very low’ cholesterol was defined as below 4.63 mmol/l. The study clearly showed an increase in cancers in people with very low cholesterol.29 In a similar study involving 7 735 men aged 40–59, serum cholesterol levels below 4.8 mmol/l were associated with the highest risk of death from all causes.30

Further studies have shown that patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma have significantly lower cholesterol values than people without the disease. It has also been noted that cancer patients with normal cholesterol values have a higher survival rate.31

In a study published in 1990, it was shown that colon cancer was preceded over a 10-year period by a fall in cholesterol levels.32 There are many more studies linking low cholesterol to different cancers, including lung cancer, liver cancer, multiple myeloma, adrenal cancer, various blood cancers and gastrointestinal cancers.33

Low cholesterol has also been associated with compromised immune function,34 depression,35 increased suicide risk,36 Alzheimer’s disease37 and Parkinson’s disease.38

The take-home message here is that cholesterol plays an essential role in our overall health. ‘High’ cholesterol and ‘unhealthy’ cholesterol are not necessarily the same thing. It is important that our cholesterol is in a healthy condition, and that does not mean simply lowering total cholesterol to as low as it can go!

High blood pressure or hypertension is a common but serious health issue that can lead to heart attack, stroke and even kidney failure. Interestingly, while up to one in three adults in the Western world suffer from hypertension, it is a condition that only affects 3 per cent or less of hunter-gatherer populations that follow a traditional diet and lifestyle.39 This suggests that hypertension is largely caused by poor lifestyle choices and can be improved by making simple lifestyle changes.

Blood pressure is the pressure in your blood vessels. Simply explained, when your heart beats, it pumps blood around your body to give it the energy and oxygen it needs. As the blood moves, it pushes against the sides of the blood vessels. The strength of this ‘pushing’ is your blood pressure. If your blood pressure is too high, it puts additional strain on your arteries and organs.

Low blood pressure in a healthy person who is not on any blood pressure medication is no cause for concern. It can make you feel dizzy and nauseous, especially when you stand up quickly from a lying or seated position, and may be caused by dehydration or salt deficiency. High blood pressure, however, is a serious health risk. The higher your blood pressure, the higher your risk.

Blood pressure is measured using two numbers. The top (higher) number is the peak or systolic pressure – this is when the heart contracts and pumps blood. The second (lower) number is the minimum or diastolic pressure – when the heart relaxes.

An ideal blood pressure is 120/80. This is generally what we find in young, lean, healthy individuals. In the West, however, elevated blood pressure is common in middle-aged or older people, especially those who carry extra weight.

There are two types of hypertension. Primary hypertension has no identifiable cause, although things like smoking, too much salt in the diet and obesity may play a role. Secondary hypertension is the result of an underlying and diagnosable condition, for example kidney disease or defects in blood vessels.

There are also different stages of hypertension. Prehypertension is diagnosed when blood pressure is between 120/80 and 140/90. Stage 1 hypertension is when blood pressure is over 140/90 but below 160/100. And stage 2 hypertension is when blood pressure is over 160/100. Your blood pressure reading must be elevated on at least three separate occasions before you are considered to have an elevated blood pressure. A temporary, slightly elevated blood pressure when under stress, for example, is not considered dangerous. Blood pressure varies somewhat from day to day, so it is recommended to diagnose someone with hypertension only if they have repeatedly high readings. If the average of either the systolic or diastolic readings is higher than the norm, it will be considered an elevated blood pressure.

It is important to understand that hypertension cannot be diagnosed from one reading only. Many people experience subconscious stress just from having their blood pressure taken in a medical environment. This is known as ‘white-coat hypertension’ (because doctors wear white coats). These people usually find that if they take their blood pressure at home, it is normal.

Primary hypertension forms part of metabolic syndrome, the disease of the Western world. As we have already discussed, metabolic syndrome is made up of a cluster of symptoms and is typically caused by a diet high in sugar and refined carbohydrates. The resultant raised insulin levels seem to lead to an accumulation of fluid and salt in the body, which raises blood pressure. In fact, one of the most significant contributors to high blood pressure is insulin resistance and high blood glucose levels. Hypertension should therefore be a primary target for dietary intervention. Chronically high blood sugar and insulin levels, as well as high triglycerides, are significantly more pronounced in individuals with hypertension than in those with normal blood pressure. The major contributor to all three of these conditions is an excess intake of carbohydrates, particularly refined grains and sugars.40

Eating a low-carb diet has repeatedly been shown to decrease insulin levels as well as blood pressure. This means that you can greatly improve your health by reducing your intake of refined carbohydrates.41

Many doctors prescribe drug treatment even at the prehypertension stage, but studies show that there is no evidence to support pharmaceutical treatment in these people.42 Although treatment for hypertension with medication is reasonable, in many cases hypertension can be corrected with diet and healthier lifestyle choices.

The traditional enemy of hypertension is salt. Most people with high blood pressure are told not to eat salt at all. Yet research has shown that eating less salt has a minimal effect on lowering blood pressure. There is simply a lack of evidence that less salt in our diet will decrease our risk of heart disease or death.43

Salt is a necessary mineral in the diet. A recent meta-analysis published in the American Journal of Hypertension found that a sodium intake of between 2.6 and 5 milligrams per day was associated with the most favourable health outcomes. The study concluded that ‘[f]or science to advance, from time-to-time, medical textbooks and dogmas need a Copernican revolution. Perhaps the time has come for the advocates of the worldwide action on salt to reconsider their salt-centric point of view of the healthcare cosmos.’44

If you are wary of salt, bear in mind that when we eat a diet of fast food and ready-made meals, it is impossible to know how much additional salt we are consuming. The hormonal effects of a LCHF diet make it easier for the body to dispose of excess salt through urine, which can explain the lowering of blood pressure that we usually see on an LCHF diet.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the hepatic (liver) manifestation of metabolic syndrome and the most frequent cause of chronic liver disease.45 At its most severe, NAFLD can progress to liver failure. It is estimated that the prevalence of NAFLD in adults in developed countries is between 20 and 30 per cent. More worrying is that the prevalence among children is on the increase.46

NAFLD is caused by drinking fructose-loaded soft drinks and eating excessive quantities of refined carbohydrates. In our discussion on type 2 diabetes, we saw that a diet rich in refined carbohydrates causes fat to be made and deposited in the liver. Think foie gras. The way to achieve a fatty human liver does not differ much from creating a fatty goose liver. Simply load in the carbs. This will cause insulin resistance and the synthesis of fat in the liver known as de novo lipogenesis. Insulin resistance and NAFLD go hand in hand, and people with NAFLD are usually profoundly insulin resistant – if not diabetic.

Many jump to the conclusion that fat causes fatty liver disease, but this is not true. Often, researchers look at what people say they eat without taking into account other lifestyle factors. So, although someone may admit to eating saturated fats, they neglect to take into account that they also eat sugar-loaded junk foods, drink fizzy drinks, smoke and lead a sedentary lifestyle. Studies have shown that saturated fat in the absence of a high-carbohydrate diet does not cause fatty liver disease.47 One study48 found clear evidence that a high-carb diet caused a 27 per cent increase in liver fat in only a three-week period.

Why is it so important to take care of our liver? Well, the liver is crucial for life. Aside from the skin, the liver is the largest organ in the body and is involved in the vital functions of cleansing, synthesis and storage. Substances such as nutrients, medications and toxins are processed, altered and detoxified in the liver, and then passed back into the blood or released into the bowel to be eliminated. In fat metabolism, the liver breaks down fats and produces energy. Liver cells also produce bile, which is important for the breakdown and absorption of fats in the intestine. It is the liver that is responsible for carbohydrate metabolism and the regulation of blood sugar as well as storage of some vitamins and minerals. It also plays an important role in the metabolism of protein and the conversion of ammonia – a by-product of this process – into the less-toxic urea, which is ultimately passed out of the body through the kidneys.

NAFLD is usually asymptomatic; in other words, you won’t feel any ill effects until the disease is quite far advanced. Most often diagnosis is made when you have your blood screened and include a liver-function test. If you are diagnosed with NAFLD, the best solution is an LCHF diet.

Studies have shown that liver fat can be significantly reduced in a very short space of time on a low-carb diet.49 In one study, in a six-day period the reduction in the amount of liver fat was about the same as it was after seven months on a calorie-restricted diet. The study concluded that overeating carbohydrates is harmful because it increases liver volume.

As we have said, NAFLD is the result of a high-carb, high-fructose diet causing raised insulin levels and the storage of fat in the liver. It should be clear that a low-carb diet is the best way to address this health issue.50

I think most of us are familiar with heartburn and that old familiar post-takeout feeling that leaves us searching the bathroom cabinet for an Eno. Until quite recently heartburn was not taken very seriously, but studies have now revealed that it can lead to serious complications, including ulceration, scarring and ultimately cancer of the oesophagus. Recent studies also show a link with irritable bowel syndrome and other gastrointestinal problems.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common digestive disorder in the United States. Studies show that 10–20 per cent of individuals experience symptoms at least once a week, and that the prevalence of GERD is increasing steadily. Drugs for acid reflux and GERD are cash cows for pharmaceutical companies. In 2014, Nexium (esomeprazole), a proton pump inhibitor that decreases the amount of acid produced in the stomach, was one of the highest-selling drugs with sales in excess of $3.5 billion.

There is a measure of risk involved with taking these drugs, one of which the pharmaceutical industry is well aware. Acid-stopping drugs promote bacterial overgrowth in the intestine, reduce absorption of essential nutrients and increase the likelihood of developing digestive disorders. When antacids were first introduced, it was recommended that they not be taken for more than six weeks. Yet today it is not uncommon to encounter people who have been on these drugs for decades.

Curing a disease means eliminating its cause. When a disease is cured, the symptoms don’t return once the treatment is removed. Acid-blocking drugs and antacids simply mask the symptoms; they do nothing to address the underlying cause. In suppressing the symptoms and not addressing the cause, these drugs lay the groundwork for long-term health complications.

What causes heartburn? We are led to believe that the problem lies in too much stomach acid. In their book Why Stomach Acid is Good for You, Dr Jonathan Wright and Lane Lenard tell us that heartburn has little to do with eating and drinking acidic foods or lying down too soon after meals. It has been well established in scientific literature that stomach acid levels generally decline with age, but the symptoms of GERD increase with age. Simply put, the risk of heartburn increases as amounts of stomach acid decrease.51

According to Wright, approximately 90 per cent of Americans produce too little stomach acid. He arrived at this conclusion after measuring the stomach pH of thousands of patients in his clinic. (While conventional medical doctors sometimes measure oesophageal pH levels in particularly difficult cases of acid reflux, they never measure stomach pH levels.)

With not enough acid in the stomach, food cannot be properly broken down, with the result that food stays in the stomach for much longer than it should.52 Proteins putrefy and carbohydrates start to ferment, causing gas, bloating and discomfort. At the same time, the low level of stomach acid promotes an environment that is friendlier to the growth of micro-organisms, which are fed by the fermentation. The build-up of gases forces the gas to reflux back up the oesophagus, causing burning. You do not need to have excess acid in your stomach to experience this burning. Any amount of acid in the oesophagus is going to cause burning, as the oesophagus is not lined in the same way the stomach is.

How does the acid get into the oesophagus? The stomach has two valves, the lower oesophageal sphincter at the top of the stomach, and the pyloric sphincter at the bottom of the stomach. While the pyloric sphincter is a one-way valve, the oesophageal sphincter is designed to open both ways. When excessive pressure builds up in the stomach, the oesophageal sphincter opens, releasing the pressure into the oesophagus. This commonly leads to the symptoms of heartburn and acid reflux.

Eventually the oesophageal sphincter may weaken, leading to chronic problems. Many over-the-counter medications and commonly prescribed drugs also weaken this sphincter.

What causes a decrease in stomach acid? We have already seen that stomach acid tends to decrease as we age, but lifestyle is another significant contributor. Adrenal fatigue, alcohol consumption, bacterial infection, chronic stress and certain medications are also common causes.53

Physiologically, when we are stressed or anxious, our body enters ‘fight or flight’ mode. This causes most of our blood flow to be directed towards our heart, lungs and muscles so that we can escape the threatening situation. In times of stress, digestion is not the body’s first priority. In a modern lifestyle characterised by stress, we seldom sit down to a meal and often eat on the run, stuffing in mouthfuls of food between phone calls and meetings. We forget to chew. The physical and chemical breakdown of food starts in the mouth and, when properly done, makes the stomach’s job easier. Our fast-paced, stressed-out, pill-popping lifestyle is thus a sure recipe for heartburn and indigestion.

There are a number of strategies for preventing and curing heartburn and none of them involve a trip to the nearest pharmacy.

Sarah Ballantyne, the Paleo Mom, has a number of great articles on her blog about restoring gut health.54 Among the approaches she advocates is reducing the carb content of the diet, as too many sugars can cause inflammation and encourage the growth of unwanted yeast and bacteria in the gut.55 She also suggests adding coconut fat and grass-fed butter to the diet, as these short- and medium-chain saturated fats help reduce bacterial overgrowth, and drinking lemon juice or diluted apple cider vinegar 10 minutes before a meal. While natural remedies aren’t backed up by a whole lot of research, many people swear by apple cider vinegar as a cure for heartburn.

Eat fermented foods like sauerkraut or drinks like kefir and kombucha, which help increase stomach acid. Fermented foods are a great source of probiotics for replenishing the gut microbiota (gut flora). If these do not appeal to you, try a good probiotic supplement.

Bone broth has wonderful anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects on the gut. A good homemade bone broth is also rich in proline and glycine, which help regulate digestion, reduce inflammation and heal the body. See page 238 for a recipe.

Be sure to get plenty of good-quality sleep. Eight hours of sleep not only gives the body time to heal, it is essential for regulating many hormones, including the stress hormone cortisol.

Stress management is also important. Exercise, meditate, pray, get a hobby, have some fun.

And remember to chew your food well!

For a long time, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) was believed to be primarily psychological. It is one of the most widespread ailments in the Western world, accounting for 60 per cent of gastroenterologists’ workload. Recent findings suggest that IBS is linked to detectable alterations in the gut microbiota.

The essential feature of IBS is abdominal pain that is improved by a bowel movement and associated with a change in bowel habits, in other words the frequency with which you go to the toilet and whether you experience constipation or diarrhoea at the time you experience the pain.

Pain from IBS may be felt anywhere in the abdomen and may also change over time. Different people describe the pain differently. Some complain of cramping, others of sharp or stabbing pain. For some the pain may be constant and debilitating. Many sufferers experience bloating, heartburn, nausea or feelings of urgency (needing to find a restroom fast). Symptoms may sometimes seem contradictory, such as alternating feelings of constipation and diarrhoea.

The criteria for diagnosing IBS are only reliable when there is no abnormal intestinal anatomy or abnormality in the biochemistry that would explain the symptoms.

Certain ‘red flags’ include anaemia or other abnormal blood test results; onset of symptoms after the age of 50 or a change in symptoms; blood in the stool; fever; unintentional weight loss; symptoms following the recent use of antibiotics; and/or a family history of gastrointestinal disease like coeliac disease or colon cancer. Never ignore ongoing abdominal discomfort or symptoms.

What exactly are gut microbiota? Micro-organisms in the human gastrointestinal tract form an intricate living fabric affecting body weight, energy and nutrition. Our gut microbiota contain tens of trillions of micro-organisms, including at least 1 000 different species of known bacteria. Although each of us has unique microbiota, they always fulfil the same physiological functions and have a direct impact on our health.

The composition of our microbiota evolves throughout our life and is the result of different environmental influences. A loss of balance in the microbiota, called dysbiosis, has been linked to a number of health problems, such as functional bowel disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, allergies, obesity and even diabetes.

There is a lot of evidence showing that IBS is associated with an imbalance in the composition of the gut microbiota. In other words, the balance between beneficial and potentially harmful bacteria, which characterises healthy gut microbiota, is disturbed in IBS patients.

There are many factors in our modern world that can upset the balance of the gut microbiota. It very often occurs right at birth. Babies receive their first exposure to healthy bacteria from the mother as they pass though the birth canal and then when they drink breast milk. Breastfed babies have a different mix of gut bacteria from formula-fed infants.

Dr Hannah Holscher and her colleagues at the University of Illinois examined the immune system development and gut bacteria colonisation of formula-fed babies. One group in the study was given prebiotic- and probiotic-enriched formula, while the other was given standard infant formula only. The study found that the group given probiotic-enriched formula had significantly increased development of disease-resisting intestinal bacteria, showing that what a baby is fed in infancy impacts the colonisation of his or her gut by gut bacteria.56

Although in many cases antibiotics are lifesaving, they are often overprescribed and a major source of disruption for our gut bacteria. Antibiotics do not distinguish between killing good and bad bacteria, and it has been shown that the mix of gut bacteria can remain disrupted from pre-treatment with antibiotics for up to four years following treatment.57

Another factor that can upset the gut microbiota is stress. We all know by now that stress is really bad for us. Studies have shown that in mice subjected to stress there was a significant change in composition of their gut bacteria.58 Gut bacteria affect immune function, which could explain why we are more likely to get sick when we are stressed.

Excessive alcohol consumption has also been shown to reduce the number of healthy bacteria in the digestive tract. Processed foods, sugars, processed seed oils, preservatives and additives also play a significant role in inflammation and gut health, and diets high in processed foods have been linked to less diverse gut bacteria.

It should be apparent by now that IBS may have any number of causes and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. However, with a clear association between IBS and dysbiosis, it makes sense to do whatever is necessary to encourage a healthy gut microbiome. No amount of medication will cure IBS. It may reduce the symptoms, but the only way to resolve IBS is to get to the root cause.

Nutrition is a key factor in relieving IBS. The kind of food we eat influences our gut ecology and can change the entire population of our gut. Cutting out processed foods and foods high in sugar is a good start. Studies have shown that in individuals who suffer from IBS the potential negative impact of foods like bread, cereals and pastries made of whole wheat, and beans, soybeans, corn and peas, is higher than in people who do not have IBS. Some individuals may have to take dietary changes a little further and cut out gas-forming foods like Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, broccoli, cabbage, celery, onions, leeks and garlic in addition to processed foods. A lot of these fall into the category of foods called FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols). Although most IBS sufferers are FODMAP intolerant, eating FODMAPs does not cause IBS – it simply worsens the symptoms. Many clinical trials show that eliminating FODMAPs is an effective dietary intervention.59

FODMAPs are essentially carbohydrates (sugars) that are fermented by bacteria instead of broken down by digestive enzymes. In most people they are a healthy source of food for gut bacteria, but in IBS sufferers they can become too fermentable, resulting in gas, bloating, pain and poor digestion.

The FODMAPs in the diet are: fructose (fruits, honey, high-fructose corn syrup, etc.); lactose (dairy); fructans (wheat, garlic, onion, inulin, etc.); galactans (legumes such as beans, lentils, soybeans, etc.); and polyols (sweeteners containing isomalt, mannitol, sorbitol, xylitol, and stone fruits such as avocados, apricots, cherries, nectarines, peaches, plums, etc.).60

Apart from adopting a healthy diet and eating habits, it is important to address other lifestyle issues too, like getting adequate sleep and finding ways to relieve stress. A good probiotic also goes a long way towards helping heal the gut, as does a good bone broth.

For more information on gut health, take a look at blogs like The Paleo Mom. Chris Kresser also has a handy downloadable eBook available on his website.61

For decades leaky gut syndrome was passed off as quackery, but new research shows that it is not only real but may be one of the causes of autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease.62

The term ‘leaky gut’ is used to describe hyper-permeable intestines. The lining of the digestive tract is like a net with extremely fine holes, which allow only certain substances to pass through. With leaky gut the intestinal lining becomes more porous than it should be, developing larger-than-normal holes. This means that undigested food molecules, yeast and other forms of waste that would not normally be allowed though, now flow freely into the bloodstream.

When ‘foreign bodies’ flow directly into the bloodstream, the body’s first reaction is to fight them. The first line of defence is the liver, which tries to remove these ‘toxins’. But trying to keep up with the constant flow of waste becomes a tough job for the liver, which is now trying to screen out all the damaging particles that the intestinal lining was supposed to have taken care of. Eventually the foreign bodies start to accumulate in the body and begin to be absorbed into the tissues, causing the tissues to inflame. This causes the immune system to go into battle mode, producing antibodies designed to fight the foreign invaders. The body essentially fights itself, and this can lead to an array of autoimmune diseases.

Over time, even chemicals normally found in foods will begin to trigger an immune response. As partially digested proteins make their way into the bloodstream, they will cause an allergic reaction. Chances are good that if you start experiencing sensitivity to a variety of foods, you have leaky gut. The allergic response will not necessarily present as a rash all over the body. Symptoms vary from person to person depending on the level of damage and the tissues being affected, but may include bloating, thyroid conditions, joint pain, headaches, digestive problems, acne and rosacea. Nutritional deficiencies may occur from a lack of vitamins and minerals, as the food in the intestines is not broken down properly, and you may experience other signs of gut inflammation like chronic constipation or diarrhoea. Left unrepaired, leaky gut can lead to serious health issues like arthritis, IBS, psoriasis, depression and chronic fatigue.

The causes of leaky gut are widely debated, but several factors have been found to contribute to the condition. As we have seen, consuming large quantities of processed food, additives, chemicals and sugar has an undesirable effect on the gut microbiota. Changes in gut bacteria can make the gut barrier more permeable.

Gliadin, a protein found in wheat gluten, is responsible for the intestinal damage we see in coeliac disease. Studies are now showing that gliadin may be a problem even for those of us who do not have coeliac disease, because gliadin activates zonulin, a protein that increases intestinal permeability. In most autoimmune diseases, we see abnormally high levels of zonulin.63 Exposure to zonulin has even been shown to induce type 1 diabetes in rats. The rats developed a leaky gut and produced antibodies to the islet cells in the pancreas.64 Wheat and other gluten-containing foods can, therefore, contribute directly to a leaky gut.

Another common food component that can damage the intestinal lining is the protein found in unsprouted grains, sugar, genetically modified organisms and conventional dairy. Unsprouted grains contain large amounts of phytates (which block nutrients) and lectins. Lectins in plants are a defence against micro-organisms, pests and insects. They are resistant to human digestion and enter the blood unchanged. Because we don’t digest lectins, we often produce antibodies to them. Lectins’ stickiness allows them to bind with the lining of the small intestine, resulting in intestinal damage.

Another factor contributing to leaky gut is chronic stress. Chronic stress usually results in a suppressed immune system, which in turn compromises the whole body. An increase in overall gut inflammation will lead to increased permeability of the gut lining.

Infection or inflammation can also lead to leaky gut. Certain bacteria – such as Helicobacter pylori, the bacteria that cause stomach ulcers and HIV – have been shown to disrupt the intestinal barrier. Any inflammation of the gut can cause a problem.

There are many medications, both prescription and over-the-counter, that irritate the gut lining. These include non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, proton pump inhibitors used to suppress stomach acid secretion and antibiotics due to their adverse effect on the gut microbiome.

Bacterial or yeast imbalances – including small intestine bacterial overgrowth, a condition in which there is inappropriate growth of bacteria in the small intestine – can lead to leaky gut. The majority of gut bacteria should be in the large intestine (colon), but factors like poor diet, illness and stress might cause bacteria to migrate to the small intestine. Yeast (usually Candida albicans) is found in normal gut flora, but can mutate into a multicelled fungus that grows branching roots called hyphae. The hyphae spread between the cells of the bowel wall, forcing them apart. Acidic, harmful micro-organisms and macromolecules are then able to leak through these openings into the circulatory system.