19

The Worrier-in-Chief

We begin to unravel, but damned if I can work out which of us is in worse condition. I have no sense of what psychosis is brewing in The Husband’s head, but if it has any resemblance to what is going on in mine, it might very well need to be flushed through with a strong course of shock therapy.

My head currently exists in three different but parallel universes, careening from extended-version memories of my past homes, to thinking about this current one, to pretending that I am part of a reality TV version of a renovation project. If these three strands should overlap, they risk causing the sort of end-of-days disaster that figures in Star Wars when the beams from the lightsabres inadvertently cross. I most definitely do not feel like a Jedi knight, and the only Force that surrounds me is the one draining our bank account.

These strands must be harnessed before they collide and do me in, but they cannot be completely eliminated: all of them are competing for time right now, and I must respect their process. Memories and imagination have needs, too, and require an opportunity for healthy venting.

To manage them, I assign to each a specific time of the day or the undertaking of a specific task where they can go off leash. For instance, when I clear rubble or engage in an activity that requires cleaning, I give my mind over to revisiting past renovations and homes. When we are in the car driving back to our rental home at the end of the day I focus on this new home, on what has been accomplished during the day, what needs my attention for work to proceed tomorrow, and what needs to be ordered for the work ahead of that. It is all on copious notes stuffed into various labelled-by-room file slots of a red-leather portfolio I carry around. It sounds very organized, but in fact my most crucial notes are contained in a single notebook, while the file slots hold the easy stuff: paint and fabric swatches, along with rough pencil sketches of what each room is to look like when it is finished. If it ever gets finished.

The third strand, of pretending I am participating in a reality TV renovation, is saved for brief moments of downtime when I am at the house, wandering from room to room and talking to myself or explaining my grand plans to an imaginary camera. I must admit, my on-camera commentary is impressive. Once you set aside the wild, dust-streaked hair and the wardrobe that looks like it was fished from the bottom of a dumpster, my delivery has a calm, decisive assurance. I can smoothly articulate the methodical progress of what has been done and what needs to be done, and I can wax lyrical about the products and the design aesthetic I have chosen, but as soon as the metaphorical camera is turned off, chaotic reality rushes back in, and I am as articulate as Porky Pig: “Abedi, abedi, abedi, that’s all folks!”

It is getting to me, this renovation. I feel swamped by its magnitude, and the way it incrementally diminishes the control I have of it. Or was that a fantasy?

Francis has the role of project manager, but my confidence in him is waning. He has made a couple of sloppy and costly blunders. The Velux skylights planned for the far end of the kitchen—the ones that were supposed to give the room the wow factor—have arrived, but they do not fit. Francis erred on his measurements. Norm from This Old House would not be impressed. Getting them to fit will mean taking the roof apart and reconstructing it at a cost of £15,000. No, thanks. Just plasterboard and paint the ceiling, I say. And since it was his mistake, I tell him he will have to swallow the cost of the Veluxes. (A few weeks later, he will try to sneak in an extra £4,000 on an invoice he sends me. When I catch this, he will be over-apologetic and blame his calculator.)

He has not made a move on the bathroom or indicated a schedule or time frame. With jocular confidence he says our house will be ready in plenty of time for our move-in date, which is five weeks away. I have already given notice to the landlord back at our Little Britain rental.

“All that’s left is to plaster the kitchen, which will be done tomorrow, and then Pedro, the tiler, arrives Thursday to do the floor. After that it’s a matter of installing the kitchen cabinets, which are being delivered today, and painting. You still want white, right?”

Yes, I say. White walls. White is the default choice of the undecided, but after the darkness in our Brixham house I want this home to be bright, and you do not get brighter than white.

“And the bathroom?” I ask.

“It’ll get done,” he says. “Paul [the plumber] is super busy right now and his wife’s expecting, so we just have to wait till he’s available. But after Pedro does the kitchen floor, I’ll get him to do the bathroom tiles.”

I move outside to take a call from Mark, the electrician. He has rewired the upstairs and roughed in the main floor. He is waiting for Francis to get the plasterer in to do his work so that the electrics can be finished. I can tell he is getting impatient.

The next day Mark drops by in the hope that a renovation fairy has flown in and magically done the plastering.

We still have not heard from the gas company about moving the gas panel, or from the energy utility about moving the electrical panel. Mark “knows a guy” who can move the electrical panel for half the cost of what the utility supplier will charge us. But The Husband, who reads the fine print on everything, who requires written and signed guarantees on company letterhead, and whose personal code does not stretch to anything that is done under the table, goes pale.

“We would save £400, not to mention time,” I reason.

“And if we get caught, we could face a fine,” he snaps.

“The last guy who used my mate was the chief of police,” Mark pipes in.

That does not convince The Husband, and I am inclined to agree with him. We are the type of people who would get caught and bear the consequences.

“I will keep calling the utility and see if we can get a date,” I say.

I make a note to call them as soon as I . . . what? My mind suddenly goes blank. I know there is someone else to call or to get after, or something to order. I look around. The place is strewn with bathroom fixtures, and kitchen appliances, packages of tiles stacked against every available wall along with lengths of pipe and wires, and tool bags. And dust. There is so much dust. It looks like Kabul after a bomb blast.

I consult my long, scribbled to-do list. The floor refinishers. And the kitchen worktops. Those are things I need to organize.

I check on The Husband. He has returned to his makeshift tea station, kettle on the boil, two coffees ready to go.

“Let me help,” I say. “I will take this to Mark . . .”

“No, not that one, this one. Milk, no sugar. That other one is for Francis.”

The Husband has assigned specific mugs to specific people. For instance, the blue mug is Francis’s, always Francis’s. The mug with the orange handle is Mark’s. Anyone who is on the premises for longer than a day is assigned a mug by The Husband. This saves him from washing the mugs during the day, because, as you may recall, we still do not have running water. He has memorized everyone’s coffee and tea preferences. In fact, he knows the trades first by their order—“one milk, no sugar” or “double sugar, one milk”—and second by their names.

I take the mug and, glancing up at his face, I notice how drawn he looks. He has not been sleeping well. In our rental home, he tosses angrily in bed, and then gets up in the middle of the night, wrenching his dressing gown from the hook on the back of the bedroom door and padding downstairs to flick on the kettle. The renovation has worried him beyond rationality. His dreams are likely populated with images of himself crawling on his belly through a storm of plaster dust, scrambling over rubble, falling down a shaft and emerging from it, catatonic with fear, only to be met with thugs who declare him bankrupt and destitute, and who turn him over to a maniacally laughing builder who threatens to put his balls in a claw-like vice.

Despite Francis being the picture of sunny optimism and assertions of “This is going better than expected” or “No problems at all. It’s really straightforward,” none of this is balm to The Husband’s anxiety. And yet, he hides it well. When he talks with the trades or with people on the street, he is the picture of cheerfulness and easygoingness, a veritable Mr. Pleasant, but out of sight and with me he is the love child of Mr. Grumpy and Ms. Worry, and godson of Mr. Grumble.

Lately, he has fixated on house insurance and door locks, and has appointed himself security officer. He asks—as if I am supposed to know—whether the newly installed French doors in the second reception room have a locking mechanism that conforms to the rigorous code the insurers demand.

“There are certainly enough locks on them,” I offer unhelpfully.

In England, windows have keyed locks on them. I have never seen this in any other country except Italy. England is almost as obsessive about door locks as it is about interior doors. Commandments eight and ten have evaded English culture. People exist about six feet from their neighbour, yet they trust no one.

My husband does not care about Italy or my views on English social behaviour.

“What if the house is broken into while renovations are taking place? Or a tradesman is injured, or if we are away for two weeks and something goes wrong?” he asks.

I throw up my hands: “What if the roof falls in, or a piece of flying rubble hits a neighbour two doors down? Why must you be so pessimistic?”

This infuriates him, my devil-may-care approach. It used to be what he found attractive about me; now he regards me like a walking four-alarm fire. His eyes say he wishes he could run as far as possible from this mess, and I daresay from me, too. Then he says, “I had my whole life planned out. My mortgage was paid off on my flat in London. I was ready to retire and travel. And suddenly you come along and put me on this, this grand tour into hell.”

“Fine,” I say. “We’ll fix up the house and sell it, store our stuff and travel.”

“No,” he says. “You want a house. You’re the one who says you need a place to put down roots. The problem is, you never do. You root and uproot.”

I turn away with my best “you do not understand me” face, but deep down I know he is right. How can I explain that houses and renovations and moving are an addiction to me; that I desperately want to settle, but as hard as I try I just cannot? That despite the adrenalin rush from upping sticks, it also causes me great stress?

A week later it all finally gets to me. One night after supper, as we slump in front of the TV craving diversion from the bickering and from the thousand and one details that get served up daily, I swiftly double over with severe stomach pains. I hyperventilate. Nothing I do will regulate my breathing. Each attempt, each gasp for air, worsens my condition. The Husband dials 999.

The paramedics are swift in arriving. They look to be the same age as my kids, possibly younger, but they are efficient, cheerful, and professional. The Husband tells them, “She’s renovating a house.” She, not we.

Electrodes are stuck onto my upper body while I am asked questions, none of which have anything to do with appliance placements, the location of the boiler, or my preferred colour of Corian worktops. They take my blood pressure and run tests. They ask me the date and year. For a brief second, I consider giving a false answer. If I get sectioned, I will not have to face the rest of the renovation. It would be left to The Husband to complete. Hmm. Wouldn’t that just do him in. At the same time, maybe being committed is the only cure for my restless obsession with homes. Still, I cannot lie. I answer honestly, and pass. My marbles are intact. Or so everyone assumes.

There is nothing amiss with my heart, the youngsters tell me.

“Take it easy,” they say.

I smile, nod, and think: Yeah, I’ll get right on that one.

Why is this renovation so much more difficult than the others? Why the hyperstress? The answer, a little-known truism, is that renovations are best undertaken solo. I had considered sending The Husband off on a hiking expedition while I dealt with the house reno: he could enjoy his journey—I could enjoy mine. But he said we could not afford to do both. I think he felt guilty about leaving me behind to do it alone.

Augmenting the stress is the fact that I cannot seem to do anything. There was a time when I thought nothing of changing a toilet seat, or unscrewing curtain rods, or cutting a hole in a wall. Now, not only do I lack the strength, I have become petrified of incompetence. I am afraid of failing.

THINGS DO LIGHTEN UP. A few days later, while cleaning out the area under the stairs, I find a small silver ring that looks faintly masonic. I also find a small plastic baggie inside which is a multi-folded piece of tinfoil. I call over The Husband. I fold back each layer of foil, and it becomes obvious what it likely contains. Cocaine. However, it is such a small amount that it has turned yellow and dried up. Does cocaine have a best-before date? Does fossilized cocaine have more potency?

We show it to Mark, who is installing a smoke alarm upstairs.

“Rip up all the floorboards!” he jokes.

We show it to Francis.

“Don’t snort it all in one place,” I say.

He peers at the minuscule remnants and says with a laugh, “If you ask me one day to put marble flooring throughout the house, I’ll know you’ve found the motherlode.”

It beats what he found in the roof void above the kitchen: women’s underwear and a nightie. Creepy.

On the way back to our rental home The Husband says, “If you actually found a pile of coke, how would you propose to convert it into money?”

“I would take it to the police.”

“So you think the police would pay you for it?”

Okay, I had not thought of that.

“Well, then we would sell it. You know, privately.”

“And then you would be arrested and sent to jail.”

What a killjoy.

I had come across a story in a newspaper about a fellow who found a suitcase full of old cash in a house he had just purchased. He was acquainted with the home’s previous owners, an elderly brother and sister, and alerted them to the stash. The notes were old and out of circulation, so he accompanied them to the bank to ensure that the money was converted properly and deposited into its owners’ account. I thought that was awfully sweet.

You live in hope when you tear apart an old home. Has someone stashed cash under the floor? Is there a false wall hiding something? Has a family heirloom slipped between the floorboards? Is there a stone in the garden marking a safe full of gold?

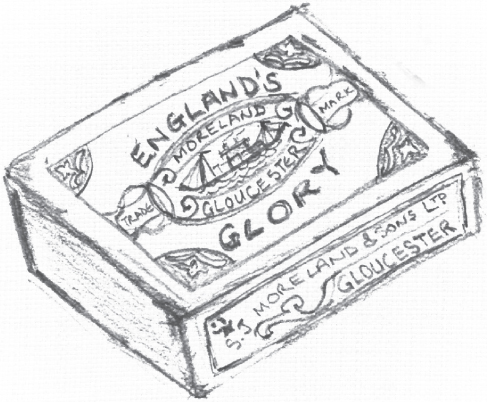

No such windfall for us. In addition to the ring and the dried-up cocaine, I find an old nail, and a charming globe-shaped glass bottle that has since been filled with scented oil and placed in the bathroom. Oh, and there was an England’s Glory match box with this joke on the back:

Wife: “How do you manage to stay out so late at night?”

Husband: “Easy. I got into the habit when I was courting you.”

These are the spoils from our renovation.