1914

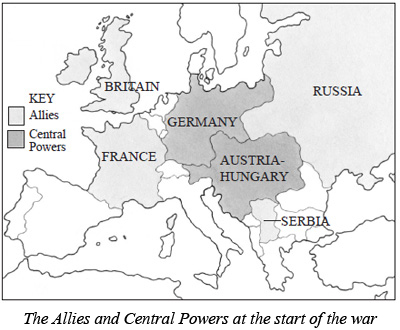

In the first four days of August 1914, the world’s most powerful nations declared war on each other. They lined up in two opposing camps. On one side was Germany and Austria-Hungary, who were known as the Central Powers. On the other was Britain and France, together with their empires, and Russia. They were known as the Allies. In the course of the war, other nations would be drawn into the conflict, too. The Ottoman empire and Bulgaria joined the Central Powers. Italy, Romania, Japan and China joined the Allies. So did the United States, despite the initial reluctance of a great many of its people. It was to be the first real world war – in that it involved countries from every inhabited continent – although most of the fighting took place on what became known as the Western and Eastern fronts, on either side of Germany.

As news of the outbreak of war spread, crowds began to gather in the hot summer sunshine, congregating in the great squares and parks of Europe’s principal cities. Far from being fearful or anxious, they were elated – like football fans anticipating a closely-fought game. Each side expected a war of great marches and heroic battles, quickly decided. The German emperor, the kaiser, told his troops they would be home before the leaves fell from the trees. The British were not so optimistic, although it was frequently claimed that the war would be over by Christmas. Only a few far-sighted politicians realized what was coming, including the British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey.

Watching the dusk from his window on August 4, the day Britain declared war on Germany, Sir Edward sighed: “The lamps are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.” His melancholy remark had a deep resonance, for the world would never be the same. Grey and his fellow citizens were living in a strong and prosperous country, with a vast empire. The war would provide a rude awakening to the grimier reality of the 20th century, completely undermining Britain’s position as the world’s most powerful nation.

Almost all the other participants in the war suffered a similar reversal of fortune, or worse. In France, half of all men aged between 20 and 35 were killed or badly wounded; its eminent position in the world would never recover. The Austro-Hungarian empire collapsed, with repercussions that can still be seen in the squabbling Balkan nations of today. The Germans ended the war on the brink of a communist revolution, and lost their own monarchy. The war swept away the Russian monarchy too, then brought the communist Bolsheviks to power. With them came 70 years of brutal, totalitarian oppression. Like many countries in Eastern Europe, the Russians have never really recovered from the First World War, and its awful consequences. Only the United States did well out of it. By 1919, it had become the richest, most powerful nation on Earth, and was set to dominate the 20th century.

Quite apart from its consequences, there is something uniquely haunting about the First World War. The Second World War was far worse in terms of its cost in human life: it claimed over four times as many victims. It was also fought with much greater brutality, and came with such horrors as the Holocaust and the mass destruction of cities by aerial bombardment. But it did end with the overthrow of two undoubtedly evil regimes – Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan – and a peace which lasted for the rest of the century. The First World War, for all its terrible cost, produced no positive results at all.

The city crowds that gathered that August had no idea what the next four years had in store. The dreadful waste of life – what British statesman Lloyd George would describe as “the ghastly butchery of vain and insane offensives” – was something hitherto unknown in modern warfare. But, worst of all, when the final shell had been fired, the final gas canister unleashed and the final submarine recalled to port, there was nothing to show for it except an awful air of unfinished business and a tally of 21 million dead. Novelist H.G. Wells called it “the war that will end war”, and the phrase had caught on. It was such a gut-wrenchingly horrible conflict, everyone hoped humanity would not be foolish enough to do it again. The Versailles peace treaty officially ended the war in 1919. One of the leading participants, French commander Marshal Foch, dismissed the proceedings as “a 20-year cease-fire”. He was exactly right. By the early 1920s, people had already begun to refer to “the war that will end war” as the First World War.

The causes of the war were many. A system of rival alliances between the different European powers had built up in the previous decades, as individual countries tried to bolster their security and ambitions with powerful allies. But, although alliances provided some security, they also came with obligations. The events that led to war were set in motion in June 1914, when a Serbian student named Gavrilo Princip assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand. In retaliation, Austria-Hungary swiftly declared war on Serbia. But Serbia was an ally of Russia’s. So Russia joined the war against Austria-Hungary, and all the other rival nations, tied to their respective alliances, were dragged into the conflict – whether they wanted to be or not.

But why should a quarrel between Russia and Austria-Hungary over a little-known country in Eastern Europe automatically involve France, Germany and Britain? It was because each was obliged to support the other in the event of war. And there were other long-standing resentments, too. Britain, then the world’s greatest empire, maintained her power by means of the world’s greatest fleet. So when Germany began to build a fleet to rival the Royal Navy, relations between the two countries deteriorated sharply. The British and French both had vast colonial empires. Germany, similarly prosperous and powerful, had very few colonies and wanted more. They all joined in the fighting to maintain or improve their position in the world.

The reason the conflict was so horrific is easier to explain. The war occurred at a moment in the evolution of military technology when weapons to defend a position were much more effective than the weapons available to attack it. The previous 50 years had seen the development of trench fortifications, barbed wire, machine guns, and rapid-fire rifles. All of this made it simple and straightforward for an army defending its territory. But an army attacking well-defended territory had to rely on its infantrymen, armed with only rifles and bayonets – and they were to be slaughtered in their millions.

Yet all the generals involved in the war had been trained to fight by attacking, so that is what they did. They had also been trained to think of cavalry as one of their greatest offensive weapons. The cavalry – still armed with lances, as they had been for the previous 2,000 years – took part in a few battles, particularly at the start of the war. But these elite troops were quickly massacred. The tactics of Alexander the Great, Ghengiz Khan and Napoleon, all of whom had used cavalry to great effect, were no match for the industrial-scale killing power of the 20th-century machine gun.

There were other ugly additions to the new technology of warfare: poisonous gas, fighter and bomber aircraft, zeppelins, tanks, submarines and, especially, artillery (field guns, howitzers etc.). Armies had long used cannons but, by the time of the First World War, these weapons had reached a new pinnacle of sophistication. They were much more accurate and fired more rapidly than they had done. The shells they fired contained high explosives, shrapnel (metal balls) or gas. Over 70% of all casualties in the First World War were caused by artillery. As artillery could be used both to attack and defend, it gave neither side an advantage. It simply gouged up the battlefield landscape, making fighting even more difficult and dangerous for the hapless participants.

The war began with a massive German attack on France, known as the Schlieffen Plan after its originator, General Alfred Graf von Schlieffen. The plan called for the German army to wheel through neutral Belgium and seize Paris. The idea was to knock France out of the war as soon as possible. Apart from neutralizing one of Germany’s most powerful rivals, this would have two other advantages. First, it would deprive Britain of a base on the continent from which to attack Germany. Second, with their enemies to the west conquered or severely disadvantaged, Germany could then concentrate on defeating the much larger Russian army to the east.

The fighting in late summer and early autumn of 1914 was among the fiercest of the war. Both sides suffered huge losses. At the Battle of the Marne, the German advance was halted less than 24km (15 miles) from Paris. By November, the armies had become bogged down in opposing rows of trenches, which stretched from the English Channel down to the Swiss border. Give or take the odd few miles here and there, the front line would remain much the same for the next four years.

On Germany’s eastern border, its armies won crushing victories against vast hordes of invading Russian troops, at Tannenberg in late August, and the Masurian lakes in early September. They had prevented the “Russian steamroller” from overrunning their country. From here on, the German army would gradually advance eastwards.

In 1915, there was an attempt by British and ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) troops to attack the Central Powers from the south, via Gallipoli in Turkey. The strategy was a disaster. Between April and December 1915, around 200,000 men were killed trying to gain a foothold in this narrow, hilly peninsular.

By 1916, the war that was supposed to have ended by Christmas 1914 looked as if it would last forever. Determined, in his own words, “to bleed the French army white”, the German chief-of-staff, General Erich von Falkenhayn, launched an attack on the fortresses of Verdun in February. His strategy was a success in some ways. The French army lost 350,000 men, and never really recovered. But Falkenhayn’s own troops suffered 330,000 casualties too, and the French held on to their fortresses. Von Falkenhayn was relieved of his command.

Meanwhile, on May 31, 1916, the German High Seas Fleet challenged the British Royal Navy in the North Sea, at the Battle of Jutland. In an all-out confrontation, 14 British ships, and 11 German ships were lost. If the British navy had been destroyed, then Germany would undoubtedly have won the war. Island Britain would have been starved into submission, as cargo ships would have been unable to sail into British waters without being sunk. The British may have lost more ships at Jutland, but the German navy never ventured out to sea again, and the British naval blockade of Germany remained intact. A pattern was emerging, of titanic struggles, vast casualties, and almost indifferent results. Worse was to come.

On July 1, 1916, another great battle began. The British launched an all-out attack on the Somme, in northern France. The British commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Haig, was convinced that a massive assault would break the German front line. This would enable him to send in his cavalry, and allow his troops to make a considerable advance into enemy territory. The attack, known as “the Big Push”, failed in the first few minutes and 20,000 men were slaughtered in a single morning. Yet the Battle of the Somme dragged on for a further five miserable months.

By 1917, a numb despair had settled on the fighting nations. With appalling stubbornness, Field Marshal Haig launched another attack on the German lines – this time at Passchendaele, in Belgium. Bad weather turned the battlefield into an impenetrable mudbath. Between July 31 and November 10, when the assault was finally called off, both sides had lost a quarter of a million men.

Two other events in 1917 had massive consequences for the outcome of the war. The Russian people had suffered terribly and, in March, a revolution forced Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate. In November, the radical Bolsheviks seized power and imposed a communist dictatorship on their country. One of the first things they did was to make peace with Germany. The Bolsheviks assumed, incorrectly, that similar revolutions would soon sweep through Europe, especially Germany. So, believing that Germany would soon be a fellow communist regime who would treat Russia more fairly, they agreed to a very disadvantageous peace treaty at Brest-Litovsk in March 1918. Germany took vast tracts of land from the Russian empire – including Poland, the Ukraine, the Baltic states and Finland. For Germany, this was a great victory. Not only had they added a vast chunk of territory to their eastern border, they could now concentrate all their forces on defeating the British and French.

But, despite their successes, events were conspiring against Germany. After the Battle of Jutland had failed to win them dominance of the seas, Germany had drifted into a policy of “unrestricted” submarine warfare. This meant that German U-boats would attack any ship heading for Britain – even those belonging to neutral nations. It was a tremendously effective strategy, but it backfired disastrously. The submarine attacks caused outrage overseas, especially in the USA, and became one of the main reasons America turned against Germany. President Woodrow Wilson brought his country in on the side of the Allies on April 6, 1917, but it wasn’t until the summer of 1918 that American troops began to arrive on the Western Front in great numbers.

The timing could not have been worse for the German army. The Ludendorff Offensive, named after German commander Erich Ludendorff, began on March 21, 1918. Forty-six divisions broke through weary British and French troops on the Somme, and swept on to Paris. For a while, it looked as if Germany would win the war on the Western Front as well as the Eastern Front. So alarmed were the British that Field Marshal Haig issued an order to his troops on April 12, commanding them to stand and fight until they were killed: “With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause each one of us must fight to the end,” it said.

But the Ludendorff Offensive turned out to be the last desperate fling of a dying army. Faced with stubborn British resistance, and fresh and eager American troops, the German advance ground to a halt. The German army had no more to give. At home, the German population, starved after four years of blockade by the Royal Navy, was on the verge of a revolution. In August 1918, the Allies made a massive breakthrough against the German front lines in northern France, and began an inexorable push towards the German border. Facing mutiny among his armed forces, revolution at home, and an inevitable invasion of home territory, the kaiser abdicated and the German government called for an armistice – a cease-fire. The time was set to be 11:00am on November 11, 1918. Fighting continued right up to the final seconds.

In his memoirs, General Ludendorff recalled the situation with anguish: “[By] 9 November, Germany, lacking any firm guidance, bereft of all will, robbed of her princes, collapsed like a pack of cards. All that we had lived for, all that we had bled four long years to maintain, was gone.”

Although there were wild celebrations in Allied cities, many of the soldiers on the Western Front took the news with a weary shrug. “We read in the papers of the tremendous celebrations in London and Paris, but could not bring ourselves to raise even a cheer,” wrote one New Zealand artillery man. “The only feeling we had was one of great relief.”

The guns fell silent. Grasses, weeds and vines gradually crept over the desolate battlefields, covering the withered trees and ravaged fields, and turning the blackened earth to a pleasanter green. Crude, makeshift burial grounds were replaced by towering monuments and magnificent cemeteries. Many of those killed found a final resting place among long rows of marble crosses, each with a name, rank and date of death engraved upon it. Others, whose torn remains were incomplete and unrecognizable, were buried under crosses marked “known unto God”.

It would be another 10 or 15 years before the charred trucks, shell carriages and tanks were taken away for scrap, and the shell holes filled in. By the time war broke out again in 1939, much of the land was being farmed again; but the faint smell of gas still lingered in corners and copses, rusting rifles and helmets still littered the scarred ground, and shell cases, shrapnel fragments and bones could still be tilled from the battlefields of northern France and Belgium – as they can to this day.