July 1, 1916

Moving images were first captured on film in the early 1890s. By the time the First World War broke out in 1914, movie cameras were an accustomed sight at any momentous event. Although the war is best remembered through photographs, much of it was also captured on black and white movie film. There are dramatic shots of artillery bombardments and full-scale infantry attacks, and chilling footage of the aftermath of close-quarter trench fighting. But one of the most haunting scenes of the war to be caught on film was not very spectacular at all. It shows a platoon of British soldiers resting before they “go over the top” on the morning of Saturday July 1, 1916 – the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

The time is about 7:25am, five minutes before the start of the attack. Filmed in a sunken road on the edge of the British front line, the men stare uneasily into the camera, faces tense with anxiety. They had been assured by their commanders that the forthcoming battle would be a walkover, but few, it seemed, believed this. Some share a final cigarette, one or two crack grim jokes, their mouths smiling or laughing, but their eyes full of fear. They all look immaculate – freshly shaven and well turned-out. For many, it would be their first time in battle. For most, it would be the last five or ten minutes of their lives. In the final moments before battle, they fix their bayonets to the ends of their rifles, and then they are gone. Within a few minutes, most were killed – caught out in the open by murderously effective machine-gun fire from the German trenches.

For a great number of the men embroiled in the Somme offensive, their journey to oblivion began in the first days following the outbreak of war. The soldiers who took part in this great battle were mainly volunteers who had joined up at the beginning. They had been dubbed “Kitchener’s Army”, after the British war secretary, Lord Kitchener, who had appeared on recruitment posters asking for volunteers.

A million men flocked to join – many enticed by the promise that they could serve alongside their friends in what became known as “Pals battalions”. The idea was a good one in theory. Battalions within a regiment would be made up of men from the same town, or village, or workplace. They trained and worked together; and when the time came, they would fight together too.

The smoky, industrial town of Accrington, Lancashire, was one such community. It provided a “Pals” battalion for the East Lancashire Regiment. When war broke out, the town had hit hard times. A strike at the local textile machinery factory had ended in stalemate. A local cotton mill had also laid off 500 men and women. Undoubtedly, many men rushed to join up for the benefit of a soldier’s pay as much as for any patriotic motive. The pay was, after all, twice what workers got in the mill or factory. Those not tempted by financial advantage faced more subtle pressures. One recruitment poster declared: “Will you fight for your King and Country, or will you skulk in the safety your fathers won and your brothers are struggling to maintain?” Another poster carried a more personal message, with a young man being shamed by his girlfriend’s father: “Look here… if you’re old enough to walk out with my daughter, you are old enough to fight for her and your Country.”

Whatever these other reasons for joining, many men also did so out of plain, honest patriotism – an unquestioning feeling of duty and love of country. Accrington was a poor town, and a good number of those who flocked to enlist were malnourished and small in stature. Many failed their medical examination and were rejected as recruits, much to their disappointment and even humiliation. But such was the outcry in the region, these standards were dropped. Instead of requiring recruits who were at least 18, over 5ft 6in (168cm) tall and with a chest measurement of 35in (89cm), the rules were relaxed to 5ft 3in tall and 34in in the chest. Age was never a problem, as it was easy enough for 16 year olds to pass themselves off as older; and this was rarely checked. Local worthies, who had huffed and puffed that the army top brass in London had “dared to think Lancashire patriotism could be measured in inches”, were mollified.

When it was time to go, the new recruits lined up in the market square and marched down to the grimy granite railway station, watched by the whole town. They milled onto overcrowded platforms and waited for the steam train that would whisk them away from their familiar world. Seeing photographs of these men smiling bravely for the camera, their lower legs wrapped in puttees (tightly woven khaki cotton bands, which was part of the uniform at the time), it is plain that they had no idea what they were letting themselves in for.

As 1915 drew to a close, the British and French high commands became convinced that the way to end the war would be one “big push” – a massive attack, on a broad front, that would be enough to break the German lines and form a gap for the cavalry to rush through. Such a tactic, if successful, would reinstate a “war of movement”, instead of the dreadful stalemate of the trenches. The spot chosen for the big push was the Somme, a chalky part of northern France near the Belgian border, named after the river that runs through it. The Somme had no particular strategic value. It was picked merely because this was the area of the Western Front where the British and French lines met – the most convenient spot for a combined attack.

But, as the new year began, the Germans had their own plans. Intending to “bleed the French army white”, wearing them down by constant attack, the German chief-of-staff, General von Falkenhayn, launched a dreadful battle of attrition on the French fortress of Verdun. Beginning in February 1916, Falkenhayn succeeded all too well, though at dreadful cost to his own army. The French army never really recovered from Verdun, and was certainly in no position to offer more than token support to the British when their own big push began in the summer.

In these circumstances, British commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Haig, and the Fourth Army commander, General Rawlinson, who commanded British troops in that section of the Front, began the final plan for the Battle of the Somme. They had a formidable army at their disposal. In August 1914, a British force of four infantry divisions and one cavalry division had been sent to defend Belgium. Now, nearly two years later, Haig had overall command of four armies, made up of 58 divisions. Most of these men were “Kitchener’s Army” recruits who had joined in 1914. Now they were trained and ready to fight, they were keen to show what they could do.

Right from the start, there was something painfully unimaginative about the tactics Haig and Rawlinson proposed, although Haig was convinced God had helped him with his battle plans. The date for opening the attack was July 1, at 7:30 in the morning, after a five-day bombardment by 1,350 artillery guns. It was all too obvious to the enemy. The five-day bombardment indicated a forthcoming attack in that sector as clearly as a skywriting biplane.

Those who had rushed to join up, in the first flush of enthusiasm for the war, were about to find out the true nature of 20th-century warfare. On the evening before the attack, the soldiers destined to take part in the first day of the battle were taken to front-line trenches. With extraordinary thoughtlessness, some squads of men were marched past open mass graves, freshly dug in anticipation of the heavy casualties to come. Then, as close to the enemy as most of them had ever been, they tried to settle into their uncomfortable final positions, and to ready themselves for the next morning. Sleep, with the artillery bombardment reaching a cacophonous peak, was quite impossible.

On the day before the beginning of the offensive, the commanding officers had briefed their men on the task ahead. They had been told that the trenches they were to attack would be virtually undefended – the five-day bombardment would have seen to that, and would also have cut the barbed wire in front of the German trenches to pieces. So confident were the generals that their men would have no problems taking the German front line that troops were sent into battle with 30kg (66lbs) or more of equipment – equivalent in weight to two heavy suitcases. This was because they were expected to occupy the German front lines and repel any counterattacks.

The Somme was not a good place to launch an attack. The major reason for its chosen location – the joining point of the British and French front lines – had been reduced to a minor consideration after Verdun. Now, only five French divisions were going to take part in the battle, along with 14 British ones. But, all along the front, the Germans occupied higher ground, forcing the British to advance uphill. The chalk ground had also made it easier for the Germans to dig 12m (40ft) underground, constructing heavily fortified positions that were mostly immune to the massive bombardment.

The five days of shelling was not as impressive as it sounded, either. The one and a half million shells fired had been produced in haste, and quality control had slipped considerably. Many were duds which never exploded. And, rather than making the attack easier, the bombardment churned up the ground in front of the German trenches, making it much more difficult to pass through.

The British artillery bombardment ended at 7:30 that morning. Then, several huge explosions rocked the German trenches. Explosives had been placed in mines dug at intervals under German positions along the 28km (18 miles) of the front designated for the attack. Following this mountainous explosion of earth, a strange silence settled over the battlefield. After the constant roar of the last five days, it seemed quite unnatural. The German soldiers knew immediately that something was about to happen. They quickly emerged from their deep bunkers and set up their machine guns.

All along the battlefront, whistles blew: the signal to attack. Troops climbed up wooden ladders placed along the outer edge of the front-line trenches. They arranged themselves into the neat lines they had learned to form in training, and waded into No Man’s Land in successive waves. Some battalions had tin discs pinned to their backs, to glint in the sun. The idea was to show the artillery where they were, so they wouldn’t get hit by shells falling short. It was a bright summer morning, already so hot the men could feel the heat of the sun on the backs of their necks.

It was Rawlinson’s plan of action that called for the soldiers to advance in straight lines to a precise timetable. Other tactics had been discussed. Haig had suggested sending advance parties to check that the wire had been destroyed. But Rawlinson rejected such ideas. He thought his inexperienced troops were incapable of following anything but the simplest plan. There was to be no flexibility or initiative, just momentum. He intended a vast, sprawling tide of men to sweep the Germans from their positions.

The first wave advanced. As they approached the German lines, those leading the attack saw to their horror that the barbed wire had not been destroyed at all. The British artillery shells had just blown the barbed wire into the air, and it had settled back again where it had previously been. There were gaps in the wire, but these had been deliberately left by the Germans to herd attacking enemy troops into “killing zones”, where German machine-gun fire was concentrated at its heaviest.

According to Allied thinking, any Germans who survived the bombardment were supposed to have become disoriented and overwhelmed by the sheer size of the force sent against them. But, instead, they just got on with the grisly business of butchering their attackers. They set up their machine guns – alarmingly effective weapons that could fire 600 bullets a minute – and mowed down the approaching British troops like swathes of corn before the scythe.

In one famous incident, a captain in the Eighth Battalion, East Surrey Regiment, gave the signal to attack by climbing onto the rim of his trench and kicking a football in the direction of the enemy lines. No doubt he was trying to allay the fears of his men with a show of devil-may-care bravado. But he was killed almost instantly, somewhat undermining the effect he was trying to create.

One of the soldiers sent in to attack that day was Henry Williamson, who survived the battle and went on to become a writer – Tarka the Otter being among his most famous works. He also wrote about his experiences in the war, and described the horror of taking part in the attack with haunting vividness: “I see men arising and walking forward and I go forward with them, in a glassy delirium,” he recorded. All around him, his fellow soldiers fell to the ground – some almost gently, others rolling and screaming with fear. Williamson pressed on through ground he described as resembling “a huge ruined honeycomb”. He watched, miraculously unscathed, as his comrades were shot to pieces. Three other waves came up behind him to meet the same pitiful fate. Londoner Arthur Wagstaff, who also went over the top at 7:30 that Saturday morning, recalled the opening minutes more simply: “We looked along the line and we realized there were very few of us left.”

In accordance with the plan, the attack went on all morning, with four waves of men going out to the same grim fate. The British army was probably the most rigid and inflexible fighting force of the war. Junior officers in the heat of battle were expected to obey their orders to the letter, even if they found themselves in almost impossible circumstances. Communications between the officers at the Front and the generals at the rear of the battle were poor too, dependent as they were on telephone lines, which would often be broken by shellfire, and runners, who carried messages from the Front to the rear, and were often killed. Soldiers and their officers had been briefed to go forward at any cost, and this they did, despite the obvious futility of doing so. Field Marshal Haig and General Rawlinson might as well have been marching their men straight over a cliff.

By early afternoon, news of the slaughter trickled back to army headquarters, and further attacks that day were called off. The casualty figures were the worst for any single day in the history of the British army, and the worst for any day, in any army, of the entire war.

Back at the casualty clearing stations to the rear of the front, men who had returned from No Man’s Land milled around in confusion, searching for a familiar face. Then came the ritual of the roll call, which established who had returned from the attack and who had not.

“So many of our friends were missing, and obviously had been killed or wounded,” remembered Tommy Gay, of the Royal Scots Fusiliers, interviewed for a TV documentary shortly before he died in 1999. “All those bullets,” he recalled. “All those bullets, and not one with my name on… I was the luckiest man in the world.”

Of the 120,000 men who took part in the first morning’s fighting, half were casualties. There were 20,000 killed, and another 40,000 wounded. That night, a slow trickle of men who had been injured in No Man’s Land, and who had spent the day hiding in shell craters under the hot sun, managed to return to their trenches under cover of darkness.

The way the attack was reported in the British press sheds an interesting light on the way news was managed during the war. One newspaper painted a picture of the opening day of the battle as a great victory, and described the disaster as “a good day for England.” Another wrote of “a slow, continuous and methodical push, sparing in lives”. No doubt such reports offered reassurance to anxious families at home, but they made the soldiers who had taken part in such attacks deeply angry.

Some battalions had come through with few casualties, but others had suffered terribly. The Second Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, for example, had started the day with 24 officers, and 650 men. At roll call that evening, only a single officer and 50 men remained. The Accrington Pals, who were among the first to attack the German line that morning, lost 584 men out of 720 – killed, wounded or simply vanished – in the first half hour of the battle. Despite the total lack of reliable news from the front, their families at home in Lancashire began to suspect something terrible had happened to their men. The regular flow of letters from France suddenly stopped. A week after the battle started, a train full of wounded soldiers from the Somme briefly stopped at Accrington station on the way to an army hospital further north. One man on the train called out to a group of women on the platform, “Where are we?” When they told him, he said, “Accrington… The Accrington Pals! They’ve been wiped out!” News spread quickly, and an awful atmosphere, like dull, heavy air before a thunderstorm, hung over the town. Then, letters from wounded men assuring their families that they were still alive began to arrive. The letters came in such numbers, it was obvious that something really big had happened. Those who received no such letter were left in a dreadful limbo – should they hope for the best or fear the worst?

Aware that its readers were desperate for information, the local paper The Accrington Observer knew the story could wait no longer. But it concealed the real news in heroic hyperbole, typical of the style of the day. “What is certain is the Pals Battalion has won for itself a glorious page in the record of dauntless courage and imperishable valour,” said the Observer, before it went on to admit, “the dead and wounded are more numerous than we would fain [willingly] have hoped.”

Then, agonizingly slowly, over the next six weeks, official War Office letters began to arrive at homes throughout the town, confirming the deaths of those killed on the first day of the Somme. For the whole summer, the Observer was filled with row upon row of photos of those who had died. The town was devastated, as the fatal flaw in the idea of the Pals battalions made itself apparent. When men in battle were slaughtered on such a scale, entire towns would be thrown into mourning.

There was to be something even worse about the Somme than 60,000 casualties in a single morning. Despite the losses, Haig and Rawlinson remained convinced their failure lay in not sending in enough men – they thought the big push had not been big enough. So, for the next five months, the volunteers of “Kitchener’s Army” were poured into a hideous grinding machine to be destroyed in their thousands, caught in barbed wire and lashed by machine-gun bullets.

There were a few successes amid the carnage. A night attack on July 14 caught the Germans by surprise, and 8km (5 miles) of front-line German trenches were overrun. Next morning, this breakthrough was followed up by a cavalry charge – the standard tactic used in 19th-century warfare when the enemy’s front line had been pierced. The cavalry men did not look quite as dashing as they once did; their red jackets had been replaced by dreary khaki. Bugles still blew and lances glittered in the hot, summer sun. Like all cavalry charges, it was a magnificent sight. But it ended in a hail of machine-gun bullets, flailing hooves and twitching bodies.

Australian troops made their debut on the Western Front, and fought with great courage. Three weeks into the battle, they captured the village of Pozières. But they paid a terrible price for their victory. So many were killed, one soldier described it as “the heaviest, bloodiest, rottenest stunt that ever Australians were caught up in.”

On September 15, 1916, tanks were employed for the first time in history. The British pinned great hopes on these new weapons; “machine gun destroyers” they called them. Indeed, for a German machine gunner in his trench, there was nothing quite so terrifying as facing a huge tank, metal tracks clanking and grinding as it lumbered forward to crush his defensive barbed wire, with bullets bouncing off its heavy steel flank. The tank would eventually prove to be one of the most effective weapons of the century – but not at the Battle of the Somme. Most broke down before they could even reach the front line.

After 140 days, when the battle finally ground to a halt in November 1916, over a million men had been killed or wounded. In all, there were 420,000 British casualties, 200,000 French and 450,000 German. The defenders, mainly men of the German Second Army, suffered so many casualties because their own general, Fritz von Below, had decreed that any ground gained by the British or French had to be recaptured at all cost. “I forbid the voluntary evacuation of trenches,” he said. “The will to stand firm must be impressed on every man in the Army… The enemy should have to carve his way over heaps of corpses.”

Having been mown down in their thousands attacking front-line German trenches, the Allied soldiers exacted a grim revenge, as the enemy exposed themselves to similar carnage in an effort to win back lost ground. “You’ve given it to us, now we’re going to give it to you… Our machine gunners had a whale of a time,” recalled one British soldier.

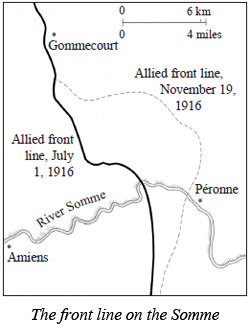

Any positive military advantage from this whirlwind of destruction was almost unnoticeable. In some areas along the 28km (18-mile) Front, the front line had been redrawn by 8km (5 miles) here or there. But, like so many other battles of the First World War, death on such an industrial scale had not served any useful purpose. Soldiers in the British army would never show such misplaced enthusiasm for battle again. From then on, ordinary soldiers would refer to the campaign on the Somme with a bitter and heartfelt loathing.

To this day, the horror, naiveté and carnage of the early hours of that Saturday morning still shocks anyone who studies the war. For those who took part and survived, it would be the defining moment of their lives. One survivor, Sergeant J.E. Yates of the West Yorkshire Regiment, recalled the effects the first day of battle had on him:

“Almost imperceptibly, the first day merged into the second, when we held grimly to a battered trench and watched each other grow old under the day-long storm of shelling. For hours, sweating, praying, swearing we worked on the heaps of chalk and mangled bodies. Men did astonishing things at which one did not wonder till after… At dawn next morning we were back in a green wood. I found myself leaning on a rifle and staring stupidly at the filthy exhausted men who slept round me. It did not occur to me to lie down until someone pushed me into a bed of ferns. There were flowers among the ferns, and my last thought was a dull wonder that there could still be flowers in the world.”