Iwo Jima, February–March 1945

The photograph that greeted American newspaper readers on the Sunday morning of February 25, 1945, would become one of the most famous images of World War Two. It shows a cluster of six U.S. Marines, their uniforms stained and dusty from three days continual combat, raising a fluttering Stars and Stripes on a long iron pole. The shot catches them in such a classic pose – pole at 45°, their bodies straining with the heavy weight and biting wind, one man crouching at the base, others reaching up as the pole is raised beyond their grasp – the image seemed to echo heroic marble figures in a Roman statue. But photographer Joe Rosenthal, who took the picture, did not even look in his viewfinder when he captured this particular moment of history. It was a lucky fluke.

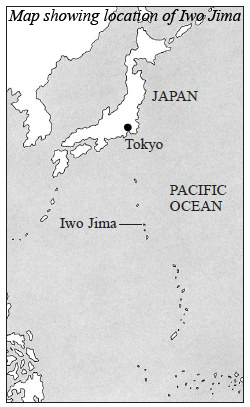

A reader who scrutinized the shot would get the impression that the men were atop some barren hill, for a pale horizon could be dimly seen below them. The hill was Mount Suribachi on the Japanese island of Iwo Jima, 1,045km (650 miles) south of Tokyo. It was the first piece of Japanese territory to be invaded in 4,000 years.

The story that accompanied the photo told how the men in the shot had struggled up Iwo Jima’s Mount Suribachi in the teeth of fierce fire from fanatical Japanese defenders, who rolled grenades down the mountain to explode among them with devastating effect. Then, overcoming ferocious opposition, the Marines raised their flag in a hail of deadly sniper fire. But it was all a work of fiction. To start with, the Stars and Stripes had been raised earlier that day, and the flag in the famous shot was a replacement. It was bigger than the original, which had been quickly removed as a regimental souvenir. The men who planted the flag had walked up the hill unopposed. Why journalists felt the need to manufacture such a story is a mystery, for the actual events at Iwo Jima were far more heroic and harrowing than any overblown propaganda report.

Pacific islands conjure comforting images of white sand, blue sea and sunshine. Not Iwo Jima. It is a bleak volcanic slab of black ash and scrubby vegetation, shaped like an overloaded ice cream cone, and frequently lashed with driving rain. The name means “sulphur island”. That evil-smelling chemical similar to rotten eggs, emanates from the dormant volcano that makes up the glowering hillside at its southern tip. The island is so small, 20 square km (8 square miles), that it only takes five or six minutes to drive across it.

During the war, many Pacific islands inhabited by Japanese soldiers were simply cut off from supplies by the allies, and left to starve or surrender. But Iwo Jima was a notable exception. Its importance lay in two Japanese air force bases inland from its stone and ash beaches. From here fighter planes scythed into the huge, silver U.S. B-29 bombers that passed daily back and forth to pound the factories and cities of mainland Japan. Iwo Jima, in American hands, would provide these bombers with a base closer to Japan, especially one for emergency landings on their return journey.

The battle at Iwo Jima was one of the fiercest, and certainly the most famous, of the war in the Pacific. On one side were the soldiers of Imperial Japan. Since the 1930s, they had been fighting to build a Japanese empire in the Pacific – conquering territories that were once part of the empires of fading European powers. These soldiers fought with suicidal bravery and infamous cruelty. They had only contempt for enemy soldiers who surrendered when defeat seemed inevitable. Even when facing certain capture, most would kill themselves rather than fall into enemy hands.

On the other side was the United States. Like their Japanese counterparts, American soldiers fought with unquestionable bravery, but it was not part of their culture to sacrifice themselves needlessly if defeat was inevitable. America had been at war with Japan since 1941, when the Japanese naval air service had launched a ferocious surprise attack on the American fleet at its Hawaiian base in Pearl Harbor. The architect of this attack, Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, was never convinced of its wisdom. “I fear we have only succeeded in awakening a sleeping tiger,” he said in response to congratulations following its success. Yamamoto was right. The United States was the richest, most powerful nation on Earth. Once war broke out, President Roosevelt devoted the entire resources of his country to winning it. The invasion fleet sent to attack Iwo Jima was an extraordinary 110km (70 miles) long. Aboard its 800 warships were over 300,000 men, a third of whom were intended to fight on the island itself.

The Japanese knew the strength of their enemy all too well. Many senior soldiers and diplomats had visited or lived in America before the war. The commander of Iwo Jima, Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, was one of them. His strategy in defending his tiny island was grimly effective. His orders to his 21,000 soldiers were brutally frank. They were outnumbered and outgunned, with no hope of rescue. The island was sure to fall – eventually. But they had a sacred duty to defend this Japanese territory to the death. Every man was instructed to kill at least ten Americans before he died. Kuribayashi, and his masters in Japan, knew that American troops were heading inexorably toward the mainland, intent on conquering their country. They hoped that American losses on Iwo Jima would be so appalling that the American public would force President Roosevelt to come to a compromise peace with Japan, so preventing an invasion, and the resulting national humiliation.

So, in the months before the invasion, Iwo Jima was turned into a formidable fortress. Pillboxes and concrete gun emplacements littered the island. Every cave held a unit of soldiers, and linking them all up was an intricate network of tunnels. There were even underground hospitals large enough to treat 400 wounded men. Japanese soldiers were not on Iwo Jima; they were in it. “No other given area in the history of modern war has been so skillfully fortified by nature and by man,” stated one post-war report.

The soldiers sent to seize this tiny island were from the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 21st divisions of the U.S. Marines, under the overall command of Lt. General Holland M. “Howling Mad” Smith. The Marines Corps prided themselves on their skill at seaborne assaults, and their fierce fighting spirit and intense loyalty. But the majority of those sent to Iwo Jima had never been in combat before. Most, in fact, were boys of 18 or 19. They were fated to be thrown into the most savage of battles at an age when many other young men would be grappling with their final year in high school, first year at college, first job, first love… most had not even left home. Some were even younger – boys of 16 and 17 who had lied about their age when they were recruited. It was little wonder that when such boys died at the point of a Japanese bayonet, or blown in half by shell or mortar, their veneer of manly toughness seared away, their last words were often a frantic, desperate cry to their mothers.

The attack began on the morning of February 19. A pink winter sunrise and pale blue sky greeted the thousands of Marines aboard the invasion fleet. They had spent a sleepless night in preparation for the assault, and their day began at 3:00am, when they were all heartily fed with steak and eggs for breakfast. Then, around 7:00am, they filed off their vast, troop carrying boats, down metal steps to fill the holds of the smaller landing craft that would take them to the island. Here, one boy who had never been in combat, recalled some sardonic advice he received from an older soldier. “You don’t know what’s going to happen. You’re going to learn more in the first five minutes there than you did in the whole year of training you’ve been through.”

The naval shelling of the island stopped at 8:57am. Five minutes later, clumsy amphibious tanks emerged from landing craft onto the soft beaches which ran for 3km (two miles) down the south side of the island. They trundled directly underneath the baleful gaze of Mount Suribachi. Such was the operational efficiency of the U.S. navy, the invasion was only an extraordinary 120 seconds behind the carefully planned schedule that had begun when the fleet left Hawaii.

The fear that clutched the hearts of troops approaching an enemy shoreline was intense. Each man knew that when the heavy steel door at the front of his landing craft was lowered into the frothing sea at the edge of the beach, he could be exposed to lacerating machine gun fire. That is, if he hadn’t already been blown to pieces by a shell before his boat even reached the shore.

Yet when the doors of the first wave of landing craft went down at Iwo Jima, the Marines were greeted only by the corrosive smell of sulphur. Although shells from their ships and planes were whistling over their heads and on to the island, the Japanese themselves were eerily silent. At first many soldiers assumed the relentless 74-day bombardment of the island by U.S. bombers, navy battleships and carrier aircraft, had wiped out the island’s defenders. But Kuribayashi had ordered his men to hold their fire while the beach filled up with American troops, tanks and supplies. When the Japanese bombardment began an hour after the U.S. invasion, it was catastrophic.

Amid the chaos of disembarking tanks, and bulldozers whose caterpillar tracks churned up the soft sand, hordes of wet, bewildered men milled around the beach. Then these men became aware of another more terrible distraction. All at once a lethal rain of shells, bullets and mortar fire fell upon them. One officer recalled that Mount Suribachi suddenly lit up like a Christmas tree – only, instead of lights and tinsel, the flashes he could see were gun and shellfire. The whole mountainside had been turned into a fortress, seven stories of fire platforms and gun emplacements, all hollowed out of its interior.

There was nowhere to hide. Marines hugged the soft sand as bullets flew over them so low they ripped the clothes and supplies in their backpacks to shreds. The carnage was hideous. Men were torn apart by shells, their bodies spread over the beach, causing even hardened veterans to vomit in horror. Others, caught directly by high explosive shells, were simply vaporized, and left no trace of human remains.

One Marine novice, having no real idea how this compared with other battles, yelled over to his commander. “Hey, Sergeant… is this a bad battle?” The sergeant shouted back, “It’s a ******* slaughter.” A minute later the sergeant was blown to pieces by a mortar. Press photographer Joe Rosenthal was on the beach that day. “…not getting hit was like running through rain and not getting wet,” he remembered. Another Marine, Lloyd Keeland, recalled: “I think your life expectancy was about 20 seconds…”

In that first hour of shelling the success of the invasion hung in the balance. But although it took a terrible toll, there were too many Marines already there, and too many still coming ashore, to wipe them off the island.

There were several things about the fighting on Iwo Jima that made it especially horrific. Such was the intensity of the Japanese bombardment that it didn’t matter whether a soldier crouched in a foxhole or charged through open land. He would be killed either way. Another was that the enemy was completely invisible. Often, American soldiers only saw their Japanese adversaries when they were dead. For the rest of the time, Marines were fired upon by an unseen foe who could all too clearly see them.

Once off the beach, Marines headed into thin scrub and grasses, and terrain peppered with blockhouses, pillboxes, caves and rocks – almost all of which held or sheltered Japanese soldiers. Every one had to be attacked, and every one caused some casualties, before a hail of machine gun bullets, or a grenade or flame-thrower put an end to its defenders. But, more often than not, it didn’t. The tunnel system that linked the Japanese strongpoints meant that a “neutralized” blockhouse could quickly become a lethal one again, with Japanese soldiers who had crawled through the tunnels, shooting at the backs of unsuspecting Marines.

Yet, despite the slaughter, the Marines were winning. The dreadful opening bombardment had not driven them off the beach, and by noon 9,000 men had come ashore. Even by mid-morning, one company from the 28th Marine Regiment had managed to cross the 650m (700 yards) that separated the furthest southern landing beach from the island’s western shore. Their casualties were daunting – of the 250 men in the company, only 37 were still standing.

As night fell, the fighting subsided. 30,000 men had managed to come ashore. But as exhausted Marines lay huddled in shallow holes and trenches, they were assailed by Japanese soldiers, who sneaked out one by one to claim an unwary life before melting away into the darkness.

The next dawn brought fierce winds and high seas – making further landings difficult. As other Marine forces began cautiously to infiltrate the northern interior of the island, the great plan for the day was to attack Suribachi itself. The task was given to Colonel Harry “the Horse” Liversedge, and the 3,000 Marines of his 28th Regiment. All that day, they edged up to the base of the mountain.

The weather on the third morning on the island brought no respite. It was a grim day to die. As the 28th Marine Regiment prepared for its assault on Suribachi, a Marine artillery barrage from behind their lines opened up for an hour. Then U.S. carrier planes swooped in to plaster the mountain with rockets. But the designated hour of the attack, 8:00am, came and went without the order being given to advance. Colonel Liversedge had been promised tanks to protect his men as they ran through open ground toward the tangle of vegetation that covered the base of Suribachi. Without tanks, his losses would be far worse than he was already expecting. But the tanks had not arrived. (They were short of fuel and shells, he found out later.) So, Liversedge decided, the attack would have to go on anyway.

When the order was passed around the regiment that they were to charge forward without tanks, raw dread swept through the men. One soldier, Lieutenant Keith Wells, was reminded of the atmosphere in his father’s slaughterhouse, when cattle realize they are about to be killed. Showing uncommon courage, Wells led by example. Despite a fear so deep he could feel it as a physical weight bearing down on him, he broke cover and began to run toward the mountain slope. He expected to be cut down in seconds. But, as he ran on, he could see hundreds of other Marines following on behind him, given courage by his bravery. Suribachi erupted into a dazzling flash of fire, and shells and bullets scythed down the charging Marines. But the men had been trained to advance at all costs, and gradually they reached the base of the mountain. Among those wounded was Lieutenant Wells, his legs peppered with shrapnel. His wounds were sufficiently bad to merit pain-killing morphine from a medic who treated him, but Wells still refused to leave his men. He directed them to destroy the blockhouses and machine-gun nests that lay at the foot of Suribachi, until loss of blood made him delirious. Gradually, men with flame-throwers were able to get close enough to do their hideous work. When the tanks eventually appeared to back up the assault, the Japanese front line on the mountain began to crumble at last.

Throughout the day, the companies and platoons of the regiment inched further up the mountain – by nightfall some had even penetrated behind Japanese lines. They lay low amid the parachute flares, and searchlights from offshore ships that combed the mountain with penetrating brilliance, fearing that every moving shadow was an approaching Japanese soldier.

On the fourth day, the Marines continued to creep forward, sometimes hearing their enemy in tunnels and command posts beneath them, but more often than not only locating a Japanese strong point when a hail of fire was unleashed on them. By now the Marines had strong tank and artillery support, and the Japanese inside Suribachi were blown and burned to oblivion. In the fading light, Japanese soldiers, increasingly aware that they were now cut off from any possible retreat, staged a breakout. One hundred and fifty suddenly broke cover, in a desperate dash down the mountain, only to be slaughtered by Marines who were getting their first sight of the soldiers who had visited such torment on them. Only 25 made it back to the Japanese lines.

At the dawn of day five, Liversedge sensed a major morale-raising coup was in his grasp. Although he suspected that many Japanese soldiers probably remained inside Suribachi, their strength as a fighting force was gone, and it might now be possible to capture the mountain outright. If he was wrong, it could prove to be a very costly gamble.

The day’s fighting began with another air attack: carrier planes smothered the top of the mountain in napalm. After that, Suribachi seemed oddly quiet. Had all the remaining Japanese fled? There was only one way to find out. A four-man patrol was sent up the mountain’s 168m (550ft) summit, each man fearing his life was measured in seconds, and that death was a footstep away. But the enemy never did open fire, and the commanding officer at the base of the mountain, Colonel Chandler Johnson, decided to risk a 40-man platoon. Lieutenant Schrier, the officer given the task of leading these men, was summoned before Colonel Johnson. He gave him a small American flag. “If you get to the top,” said Johnson tactlessly, “put it up.”

As Schrier’s platoon snaked higher up the mountain, they caught the eye of every man on the beach and island close enough to see them. Then word got around. Even those offshore, in the vast armada that surrounded the island, trained their binoculars and telescopes on the thin line of men. At any second, both the platoon and their thousands of spectators expected the remaining Japanese on Suribachi to open up and cut them to ribbons.

The platoon advanced gingerly, and with great caution. At every cave they came to, they tossed in a grenade, in case it contained enemy troops. But, after forty tense minutes, they stood breathless at the top, not quite believing they were still alive. At 10:20am they raised the Stars and Stripes on the summit, using a piece of drainage pipe as a flagpole. When the flag went up, a huge cheer rose from the throats of the thousands of Marines who had been watching below. Offshore, warships sounded their horns, and men onboard hollered in triumph. “Our spirits were very low at that point,” recalled one soldier, Hershel “Woody” Williams, “because we had lost so many men and made so little gain. The whole spirit changed.” Although the fighting was far from over, seeing the American flag flying over Iwo Jima’s highest point convinced every Marine that they were there to stay.

Around the flag, Marines stood uneasily, posing for army photographer Louis Lowery. With the flag fluttering in a strong breeze, and their silhouettes standing out on the top of the mountain, they would soon be the target for every enemy sniper and artilleryman within range. One of the soldiers present recalled, “It was like sitting in the middle of a bull’s-eye.”

Sure enough, the cacophony touched off by the raising of the flag had alerted the Japanese. The ragged soldiers left on the mountain began to emerge from hiding places. They tossed grenades or loosed off a few rounds toward the Marines, who dived for cover and began to fight back. But, amazingly, no one was hurt, and soon the mountain settled down again to a sullen silence.

There were indeed still several hundred Japanese troops left on Suribachi, but they had lost the will to carry on. Strange as it seemed to the American Marines, most chose to kill themselves rather than fight to the death or surrender.

Watching the flag-raising from the beach below was “Howling Mad” Smith, and none other than the U.S. Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, a man so important that he would later have a large aircraft carrier named after him. (The USS Forrestal saw service in both Vietnam and the first Gulf War.) Forrestal instantly understood the significance of that moment for the reputation of the Marines. He turned to Smith and said: “The raising of that flag on Suribachi means a Marine Corps for the next 500 years.”

Forrestal decided he had to have the flag as a souvenir, but when his request reached Chandler Johnson, the colonel spat, “To hell with that!” He was determined to keep it for the Marines. With an undignified race on to be first to grab the flag, Johnson craftily decided that a much bigger replacement flag was called for. One was quickly located from a large landing craft just off the beach. Significantly, this flag had itself been rescued from one of the ships sunk at Pearl Harbor.

So it was that Captain Dave Severance, and six men from Easy Company’s second platoon walked into history. Like Lieutenant Schrier’s men before them, they worked their way up the hill with great caution, reaching the summit around noon. A large iron pipe was found to serve as a flagpole, and stones were piled up to hold the heavy pole in place. Near the summit was Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal. On an impulse, he went over to record the scene. He was still preparing his equipment when the flag was raised by six Marines. Rosenthal instinctively pointed his camera and clicked the shutter without even checking the shot in his viewfinder. Thus, in one four-hundreth of a second, the most famous American photograph of the war was taken. At the time, no one could possibly have grasped the significance of this particular moment. No one cheered. After all, it was just a replacement flag. The men of Easy Company returned to the fighting, their task complete. Of the six who raised the flag, three would subsequently die in the continuing battle to capture the island.

Rosenthal sent his roll of film off on a flight to Guam, a thousand miles to the south. Here it was developed and printed up, passed through army censors, and finally reached the desk of John Bodkin, the local Associated Press picture editor. It was his job to decide which shots were worth transmitting back to the bureau in America. Bodkin knew immediately he had a shot in a million. “Here’s one for all time!” he told his staff. Sure enough, within two days of the shot being taken, it was on the front page of almost every American paper. Its arrival on picture desks was timely. At that moment, Iwo Jima was currently the most written about hot spot of the entire war, and public interest was massive. Rosenthal’s shot became an icon, and prints were sold in their millions, to be framed and placed on workplace or living room walls, next to shots of sons and fathers in uniform. The image even appeared on 137 million postage stamps. After the war, a huge statue based on the photograph became the U.S. Marine Corps memorial in Washington.

Perhaps the same worldwide fame would have greeted Louis Lowery’s shot of the first, actual, raising of the flag, had it reached newspaper picture desks first. But it didn’t. Army shots always took a much slower route back home than those of commercial news organizations.

Kuribayashi and his high commanders had been correct in assuming the American public would be shocked by Marine casualties. They were. Within two days there had been more casualties than in the entire five-month campaign at Guadalcanal, in the South Pacific, earlier in the war. It was unquestionably the American military’s costliest operation so far. But the picture of the flag being raised less than a week into the campaign seemed to offer a major vindication. It said, quite incontrovertibly, that whatever their losses, the Marines at least were winning.

But that was only part of the story. Suribachi may have been the most strategically useful spot on the island, but its conquest was mainly symbolic. Another month of slow, agonizing, fighting dragged on before the Japanese were wiped out. Of the 21,000 men under Kuribayashi’s command, only 216 were taken prisoner. The last two of these surrendered in 1949, when they found a scrap of newspaper reporting on the American occupation of Japan. They had kept themselves hidden in the maze of defensive tunnels inside the mountain for almost four years, pilfering food from U.S. army supplies to keep from starving.

The American casualties were also horrific. Few of the Marines who landed on the first day escaped unscathed. Altogether nearly 6,000 were killed, and over 17,000 were wounded. Kuribayashi’s men had sold their lives with at least one or two American casualties. Survival seemed a matter of pure luck. Lloyd Keeland, caught up in the initial bombardment on the first day of the landing, fought for 36 days, although he was injured several times. He survived a night-time sword attack, waking up to hear a Japanese soldier attacking the man next to him. On another occasion, he stood talking to a soldier who was shot in mid-conversation. After the battle, on a troop ship home, Keeland was haunted by nightmares of combat, one time waking to find he was strangling the man in the next bunk.

But the battle had served its purpose. Japanese fighter planes no longer harassed the American bombers that passed over the island. In the final months of the war some 2,400 damaged B-29s, which would otherwise have crashed in the sea, were able to land at Iwo Jima. The 27,000 U.S. airmen on board these huge bombers were saved from a near certain death.