Men in Irons—

WHAT, Briscoe? Don’t tell me you haven’t shaved! And your clothes, Briscoe. So rumpled and dirty! And your face! Why, all week we’ve been feeding you up like a prize beef on bread and water and you haven’t even the good grace to get fat about it.”

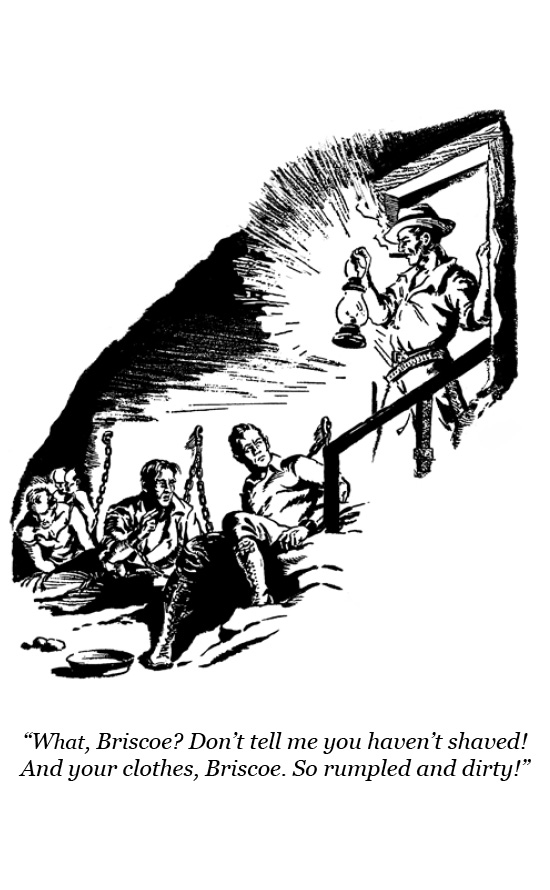

Schwenk stood in the roughly hewn doorway of the cavern. His eyes were withdrawn into the fat folds of his face and his thin mouth was curved in a crooked, gloating grin.

Schwenk went on, “You’ll have to pardon my discourtesy, Briscoe. I’ve been so very busy I really haven’t had time to entertain you properly. But we’ll remedy that very shortly. Very, very shortly, Briscoe. And how are the rest of your fine mutineers? Why, don’t tell me they look seedy, too! Gentlemen, gentlemen, have you no pride of appearance whatever? Take your cue from Briscoe. See how neat and tidy he’s kept himself!”

“Go away,” muttered Briscoe. “Go away and drown yourself or something. Go take some cyanide.”

Schwenk laughed and came forward in the dim, greenish light. He sat down on a coral stone, facing Briscoe, studying him, grinning.

Briscoe, after a week of hell, looked much the worse for wear. Sleeping on sharp stone, eating nothing but dry bread and drinking nothing but scummy water had caused his cheeks to sink in until his face was little more than the caricature of a skull. But if Briscoe looked bad, Mike, Banjo and Tim looked even worse. The natives did not appear as bad off. Indeed, they had hardly changed at all, due to the full ration brought them every day. It amused Schwenk to feed them well.

“I came down for a good purpose, Briscoe,” said Schwenk. “You should be very flattered that I come to tell you the news first. I’ve told no one else, you know.”

“Keep your news and go away. This place stinks enough now.”

“You have a pretty way of expressing yourself, Briscoe. You make me hesitate about confiding in you. But then, I’ve always been very considerate of you, Briscoe, and I really wouldn’t like to leave you ignorant of this affair.”

“What affair?”

“Ah, you’re interested now, eh? I wanted to tell you about Martin, Briscoe.”

“What about Martin?”

Schwenk drew a long breath and sighed. “Poor chap. His creditors have sent word that they will be held off no longer. He must pay or go to jail, Briscoe. But of course I couldn’t help him, even if he is an old friend.”

“Sabotage didn’t pay him well enough, that it?” said Briscoe, propping himself up against the stone and swinging his irons into a less weighty position.

“Sabotage?” spat Schwenk in a surprised voice. “How did you … What gave you such silly ideas, Briscoe?”

“You mean what gave you and Captain Martz such silly ideas. Good God, Schwenk, do you think you can run the whole world?”

“Briscoe, you give me pause. You make me wonder about things. I’ve recently had all your baggage searched, old fellow. On a grip we found the initials L.F. On a binocular case we found the initials L.B.F. On a picture, Briscoe, we found L.F. I’ve been wondering what your real name might be. Not Fremont, perhaps?”

“It’s hard to tell, isn’t it?” said Briscoe.

“Not so hard. I also found a little magazine in your trunk, Briscoe. The Army and Navy Register. It said something about First Lieutenant L.B. Fremont being granted a year’s leave of absence without pay.”

“Is that so?” said Briscoe. “Why do you suppose an Army man would want a year’s leave? Very strange, isn’t it?”

“Not so strange. Both you and I know that a man named Fremont is buried up on that high ridge behind the slave houses. Died from fever, poor fellow.”

“Well, you at least buried him.”

“Of course. But I don’t think I’ll have to bury you, Briscoe. No, I don’t think so. Sometime when you haven’t anything better to do, hitch yourself down to the float at high tide and watch the sharks coming in through the reef. There’s a big one down there. About thirty feet long, he is. A man could walk upright through his mouth, but of course I don’t expect you to be walking about that time.”

“Schwenk, you bore me.”

“That’s unfortunate, Briscoe. Why don’t you get up and leave, eh? But none of this. Did I tell you about Martin?”

“Go ahead. I’ll wait until you’ve finished.”

“Thank you,” said Schwenk. “The poor man is badly in debt—”

“You said that once. But fifty thousand dollars will get him out of debt, won’t it?”

“Briscoe, you amaze me. That’s the exact amount. However, I really couldn’t give away fifty thousand dollars, you know.”

“Of course not. So you are going to take the girl off his hands. Go on, Schwenk.”

“Damn you!” yelled Schwenk, suddenly. “How did you find that out?”

“I know you and your ways, that’s all. Calm yourself, Schwenk, and pray continue. I won’t interrupt.”

Schwenk was silent for a long time. Finally he went on. “I knew what you were going to do. You knew what I was going to do. You’ve lost. Diana thinks a great deal of her father. She’s willing to save him by marrying me. I came down here to tell you just this: Tomorrow night, if you listen hard, you might hear Rengarte reading the ceremony. Good afternoon, Briscoe.”

Schwenk got up to go. He looked over the eight prisoners and chuckled. He turned and started through the doorway.

“Schwenk,” cried Briscoe. “You can’t do that to her.”

“If her own father doesn’t object, why should you? Goodbye, Briscoe. I’ll be too busy to see you again.”

The door slammed. A lock rattled.

Mike Goddard muttered, “Rengarte ain’t no priest. Anybody can see he ain’t. She won’t be fooled by that.”

“If he shaved,” said Briscoe, “he’d fool anybody. Banjo! Can’t you do something about these locks?”

“What have I been doing for a week?” complained Banjo. “Knitting?”

“If you could lift that stone there, Mike,” said Briscoe, “you could bang it down on this chain—”

“We tried that and the stone’s too soft,” said Mike.

“Tim,” pleaded Briscoe, “can’t you work a bolt out of the wall?”

“That ain’t coral,” said Tim. “That’s concrete. You might know that Swiney would think of all them things before we would. There ain’t any way out of here at all, Briscoe. You been scurrying around like a squirrel in a cage looking for a way out and you can’t expect a new one to jump up and crack you one. Besides, how would we get out of the cavern down there?”

“I’d swim for it!”

“You’d swim,” said Mike, “about two feet, straight into the mouth of a shark. Now quiet down. Going nutty isn’t going to get you anywhere.”

“But I can’t sit here and let Schwenk go ahead with that farce. Maybe I could tell that girl that Rengarte—”

“You couldn’t tell her anything,” said Banjo. “She wouldn’t believe you if you said white was white.”

“That’s right,” agreed Mike. “And besides, I’m not worried about any dame. I just want to get out, that’s all.”

“Banjo,” said Briscoe, “what did you do with those keys when they caught you outside of the gun shed?”

“Threw ’em into the brush. Think I wanted them to find them on me?”

“And they’re still there?”

“Unless Schwenk took a magnet to find them,” said Banjo.

“Look here,” said Briscoe. “You’ve got to help me. If all of us hauled in on these bolts of mine, maybe I could pull them—”

“Jesus,” said Mike, “you’re going crazy! We tried that the first night, don’t you remember? Forget about that dame. You can’t help her. We’ve got a whole week, maybe more, and Schwenk might let us go after—”

“Mike,” said Tim Sullivan. “I’ve known you for five years at least and if I’ve said it once, I’ve said it five hundred times. Just bein’ optimistic won’t get you out of a hole. You’ve got to do something besides wish. You know just as well as I do that old Schwenk wouldn’t let us live if he was to get ten thousand dollars cash apiece for us. I told you something like this would happen. We was doing all right. And you had to go and get this crazy idea and Briscoe had to get romantic and try to steal a skirt right out from under Swiney’s nose and here we are. That’s what comes of bein’ hopeful, I tell you.”

“Aw, we had a good chance,” defended Mike.

“We did not!” disputed Tim.

“Then why’d you come in on it?” said Mike.

“Because … well … Anyhow, you won’t bite these chains in two with your bare teeth.”

Banjo sighed, “If I only had a file.” He squared himself against the wall and brightened up. “They put me in jail once down in Rio. ’Dobe walls three feet thick, a window too small to squeeze through, a lock on the door that took a key as big as your arm. They sure had me that time. They was going to put me in front of a firing squad after the judge decided I really had killed the guy. It wasn’t a very fair trial because they never let me talk at all. They just let a cop up and say that he’d seen the corpse with the knife in it, and they had a dance hall dame say that, yes, she seen me do it, and there I was.

“But I fooled them. They were going to use me for a target at dawn sharp, and while it was still dark they sent a priest in to me so I could confess. The priest was a funny little guy with a voice way down in his boots. He says, ‘Son, to me you can confess your sins.’ He give me a brass crucifix to hold and I knelt down and made up a lot of stuff and pretty soon, when I’d finished, he grumbles, ‘My son, is there any last request I can fulfill?’

“Right then I saw light. I says, ‘Yes, Father, there is one last request. Allow me to have a half-hour in which to pray and then let me die with this holy cross clutched agin my sinful breast.’

“So he says, ‘My son, that is okay with me,’ and he leaves me the cross and I knelt down until he got out of sight.

“It was still pretty dark and I began to pray in a loud voice so the guard outside couldn’t hear what else I was doing. You know how flimsy they make their jail crucifixes in Rio. Well, it wasn’t any trick at all to bend out one of the feet and one of the hands and stick that there cross right into the lock. I turned it and I was free just like that.

“I batted the guard over the head with it, took his rifle and lammed for the beach. I got aboard an outbound freighter just one gulp and a gasp ahead of the police.

“I never did think much of religion until then, but I know it’s mighty useful now.”

“But you ain’t got any cross,” growled Tim. “So why bring it up just to make us feel bad.”

They were quiet after that. They could hear the waves mourning down in the cavern. Overhead, at times, they could hear footsteps.

Briscoe tried to sleep, but he had too much to think about. For hours he lay staring at the dark roof as though trying to project his thoughts through it.

As nearly as Briscoe could figure, it must have been early morning when the door creaked again.

First he saw a candle and then, behind and above it, a face.

Diana!

The upcast golden light made a halo about her head. Her eyes were too bright and frightened.

She stopped, held the candlestick higher.

“Briscoe,” she whispered.

With a harsh rattle and clank of chains, the eight sat up. Their hollowed eyes and sunken cheeks and unshaven faces made a terrifying picture against the rough wall.

Diana stepped back hurriedly, almost dropping the candle.

“It’s all right,” said Briscoe soothingly. “These irons have held for a week. They’ll hold another five minutes.”

“I saw Josef come down by that door last night,” whispered Diana. “He said that you were dead. He said your longboat had been found overturned on the banks of the Zaga River. There are five searching parties of natives out looking for you.”

Briscoe’s heart began to beat faster. Eagerly he sat forward, straining at the iron which held him. “If you tell them where we are, they’ll attack and free us!”

“I … I can’t do that. They would murder Schwenk.”

“Good!” spat Mike. “Don’t hold off on my account.”

“But I couldn’t let them do that,” said Diana. “Josef has been very kind … and … and after all, you mutinied and tried to murder all of us.”

“Then you believe that,” said Briscoe, harshly. “You believe Schwenk, the filthiest cutthroat in the Celebes. And I suppose tonight you’ll marry him.”

Diana stood straighter. “I came here to find if there was anything I could do to lessen your misery. I have worried about it since the night I saw the longboat put into the cavern below and then come out empty. But I did not come here to listen to you curse a man who has been of the greatest aid to both my father and me.”

“You believe he’ll really marry you?” snapped Briscoe.

“What do you mean?”

“You didn’t know that Schwenk already has a wife in Australia?”

“How could you know that? You are trying to turn me against him so I will procure your release.”

“Tonight,” said Briscoe, “you will be ‘married’ by a former veterinarian in the French Army. A man named Rengarte.”

“You cannot malign a priest!” said Diana.

“You came here this morning to help me,” said Briscoe. “If you believed everything which has been said about me, you would not have given the matter another thought.”

“I was … I think your punishment is just. A Dutch jail may teach you that loyalty is a better course.”

“Not a Dutch jail,” said Briscoe. “That’s another lie. Schwenk is going to feed us to the sharks, no matter what he tells you about it. If you go through with this marriage, if you turn aside everything I say to you—”

“You cannot play upon my sympathies, Mr. Briscoe. I have seen too much about you and your companions in Josef’s papers. Wanted men. Renegades. Thieves and murderers. Oh, I’ve seen the posted reward papers. Mike Goddard, Tim Sullivan, the notorious Banjo Edwards.”

“But you’ve seen nothing about me,” said Briscoe.

“You are mistaken. Josef has just received your complete record from Nordyke, captain of the Rangoon. I was mistaken about you. You do not merit aid, Mr. Briscoe. I hope … I hope the Dutch courts give you life!”

She tossed her head angrily, turned to the door and opened it. “To think that I came here to help a liar as well as a criminal. To think you would dare suggest that I aid you in starting a wholesale mutiny among the workmen. I am sorry that I troubled you, Mr. Briscoe.”

Mike groaned when she had gone. “You said the wrong thing, Lee. You ain’t got any tact at all. ’Course she thinks Schwenk’s a damned saint. He wouldn’t show her anything crude until he had her, would he? ’Course she thinks you’re a liar. Good God, Briscoe, you ain’t no diplomat at all. Why didn’t you moan and whimper and say you was sorry you’d been bad and that Schwenk was a good, kind man and you only wanted a chance …?”

Clink!

Clank!

Rattle!

“There,” said Banjo, with a sigh of relief.

They whirled and stared at him and saw that the impossible had happened. Banjo’s irons were in a heap about him and Banjo was free!

“How the devil …?” began Briscoe.

Banjo moved stiffly across the chamber and knelt at Briscoe’s side, tugging at the bracelets.

“What happened?” demanded Briscoe. “Have you been holding out on us?”

“Me?” said Banjo, grieved. “Women are saints. I never thought they was much use, but now I’m a changed man. I’ll go through life hand in hand with women and religion, s’help me. You made her mad. She tossed her head, zip, like that and …”

Grinning, Banjo held up a hairpin.

“They shed ’em like a dog sheds hair,” grinned Banjo, slipping the unlocked irons from Briscoe’s wrists.