WOMAN OF ACTION

I feel ready for this

AT IRINA ALEKSANDER’S, JULY 23, 1943

I didn’t run to Jaeger with my pain, like a child to its mother. I wanted to take the shock, survive it, mature, learn to suffer without dying. And I have triumphed. I am strong again. I haven’t died. I took my body to the beach, to the sun, recuperated. I had bad moments, but I haven’t died. My senses are alive, and I am no longer ill. I have eaten heartily. Monday I will make love with Chinchilito. Tuesday I will go to Southampton. I will have more lovers, many of them. I will play, be alive, dance, sing, swim—not die—not be caught in tragedy, paralyzed or enslaved. I will defeat tragedy.

The image which has supported, inspired me, upheld me, put me to shame, is strangely that of the Soviet Captain Valentina Orlikova, with whom Irina had a friendship. Her photograph gave me the same shock I felt when I first saw it on a magazine cover and heard about her life. A shock of admiration, of love, of identification. She was born February 22.

Life lashes out. I must turn my face, receive the blow, and continue. Every day Valentina faces death, separation from her husband and child, the great tragedy of war, greater catastrophes, universal tragedies. Il y a une self-indulgence dans la souffrance.

JULY 26, 1943

I felt I couldn’t write about the days spent with Irina under her roof, but now I am back in New York with the captive image of her Rubens coloring, her flaming hair and delicate roses, her soft curves, her deep voice, her irrepressible laughter, her nervous tension which is causing her illness.

For the first time in my life, I felt natural and relaxed while staying with people. I didn’t strain. I had confidence. I was passive (I arrived still ill).

Irina said when I left: “There are no visitors coming until August 15. There will be a hole after you leave.” Amitié passioné—always going as far as a friendship can go without sensuality. I take her bare arm. It is soft, and the skin is so fine, so fine. I left too soon.

I have been captain of the invisible ship, the invisible captain of Hugo’s life, of Henry’s, Gonzalo’s, or Thurema, Frances, so many of them, yes. But am I doomed to invisibility and mystery!

Valentina has a real ship, a real uniform, a real medal, a real direct love from all.

And I? I am weary of the ghostliness of the soul and wish to appear on the surface!

As I write, I am bruised and exhausted from a long orgy with Chinchilito. The independent Chinchilito is now more personal in his lovemaking. Not only does he take me with greater passion, but holds me afterwards with tenderness, a personal tenderness. We talked together delightfully, whimsically. And then, when I thought he had enough, he took me for the second time, something Gonzalo has never done. The sort of feast I like, which satisfies me, quiets me. He feels my detachment from Gonzalo and grows nearer.

In this new physical world I feel strange at times. Certitude. Like the sunlight, I see the new hand of Chinchilito upon my hips, a blond, fair artist hand. As he talks I look at his mouth, his lovely and dazzling teeth. There is friendship, gestures like those of love at moments, paroxysms of desire mounting.

The only element missing is the emotion, the deep inner burning consuming the feelings, but there is the freedom from pain. His wife doesn’t exist for me. I powder myself at her dressing table, I see the Arden face tonic, the Arden face powder, dark hairpins.

Of course, I am deceiving myself. To possess the physical world, I am surrendering my emotional depths, the feelings that were a reality of another kind. I lived by them. I also died for them, the feelings indissolubly bound to torment.

How many, many layers the being has, how many folds and fissures the flesh has. A body like mine is shaken in the act of possession, and because of its capacity to vibrate, the feelings too get shaken somewhat (as if the dice alone could not be shaken without affecting the box). Yes, as he kneels, he shakes my whole body with his power; he is a powerful instrumentalist. But the deep emotions are dormant. How easily Albert reached down to them.

Of course I am aware of the simulacra.

Because I have often experienced orgasms of the soul, my lonely body, when deprived of its emotions, is not deeply possessed yet. It is only pretending. Yet life does come from these simulacra—yes—in the playing and pretending there is a growth too.

JULY 27, 1943, SOUTHAMPTON

Caresse got me an apartment in the plumber’s house across the street from the Old Post House, which she manages. I have plenty of rooms, two bedrooms, a sitting room, a big kitchen and bathroom for the incredible sum of $50, but the atmosphere of the place is ugly, chichi and snobbish. I don’t like it. I try to think of the beach only, health and recuperation.

I am getting hardened to the blows. My body is more resilient. I feel nothing when Gonzalo telephones me that he is coming tomorrow. I feel drained. All I want is the physical warmth of sensuality. That is why I sought out Caresse, whose sensual life is full and excessive and happy. She has an “official” lover, whom we call the husband, because he is protective, elderly, and whom she doesn’t desire. She has a young son lover, amants de passage, amants d’une nuit, etc.

When I think of Albert, it is with an acute agony, but it passes like a heart attack.

What can I make of this moment, the present? A day at the beach, at the exclusive beach club where at least everything is pleasant to the eyes and people have an assurance, an ease I have not seen among the poor and bohemians.

Sleep. Rest.

The solitude I hate, yet I can’t bring myself to invite Frances or Thurema.

I want lovers.

So.

MONDAY, AUGUST 9, 1943

Thurema and Jimmy came for two days and cheered me. Hugo comes on weekends. August passes, and my love for Gonzalo turns to tenderness…

Sadness.

I had the courage to surmount death, to continue to live, but I find nothing to live for. I cannot live without passion.

SEPTEMBER 3, 1943

I tried to pass through the ordeal of the loss of Albert alone, tried to survive it, tried to take it with strength, health, but in the end I have lost the battle. I have fallen again into my anxieties, my obsessions. I have no desire to live. I think of my work and feel blocked by the stupidity of the response it gets, by its inadequacy, by the fact that I am writing for people who don’t understand me. There has been complete silence surrounding Winter of Artifice, never any public mention of it. A few individual responses, that is all. How can I print another book? Where will I find the courage?

My body is starved.

My only possession, as always, is Hugo’s love, Hugo’s devotion, Hugo’s passion and desire, Hugo’s worship, Hugo’s protection, Hugo’s total abandon to me, Hugo surrounding me. That is all I have, and ever have had. The rest was illusion and delusion.

Dream: A ship is sailing towards Europe at top speed. I can see it through the enormous lens of a movie camera. But suddenly I am aware that I am in another ship on which is perched the movie camera, sailing towards Europe even faster than the other ship. I see that I am inappropriately dressed in a white lace dress. Then I feel very insecure because the highly elevated ship (to hold the camera) makes it top heavy, and as it is racing against the other ship I feel its height makes it dangerous, apt to overturn. Now we are facing the narrow canal I always see in my dreams. I say to Joaquín, “There it is, I recognize it.” It is always apparent that the passageway is too narrow for the large ship. Now we enter it. It is bordered with trees and lined all along with prison bars. Behind these bars are all the prisoners of the war. I see them as we see them in pictures, crowded, idle, ghostly…

I told Hugo I am tired of being a ghost, that I want a real ship, a real medal, action. I always succeed spiritually but fail in action. I failed to become a dancer, a psychoanalyst, and now a writer. Yes, I know my value, but my value always condemns me to the coulisses, the mystical, the invisible, the mysterious. I am tired of being a mystery. I want to take form, to appear, and one only gains visibility by action. As it is, I only appear in people’s dreams, haunt their souls, and they refuse me power in reality, refuse to pay me, refuse to review or recognize me as a writer, condemn me to obscurity. No, I want power and daylight. I am coming out in the open now. I am no longer going to be the transfer of blood that I have been for others. I am going to BE, be myself directly, openly. Every act of mine has been subterranean, mystical, incomprehensible, reprehensible, and suffocated. Just as I cast off my romanticism and magic, I cast off my old form of action. Like Russia, I am going to transmute from hysteria to health, from emotion to action, from weakness to strength on earth.

But how? How? How?

Men fear woman’s new development. Imagine kissing a woman corporal, a sniper, a captain, a welder. Imagine how they will dominate! It will be impossible to regard them as women or to dominate them! Men’s fear. Gonzalo’s, even Hugo’s fear! Their power is threatened, and their masculinity is endangered.

I know how to answer this.

Women are much more dangerous to men as thwarted wills, perverted power-seekers who dominate man indirectly because they cannot use their own power directly. Their will is frustrated because they are always forced to fulfill themselves through another, in the husband, the child, and if she is husbandless and childless, then she is a failure, an incubus, a sick, incomplete cripple.

SEPTEMBER 4, 1943

I dreamed that I was going to die in one week. Then someone was reading a story, a serial about a character with whom I identified myself. I asked this person: what happens to the woman this week? It’s a story of her death, and I am sure this is an indication of my own. I was not sad, I was only worried about the diaries. I wanted to burn them.

I cannot fight my way out of death. It has descended on me, engulfed me. Everything seems like death to me: New York, the press, printing the stories, life with Gonzalo. I dread the people I am going to see again, none of them give me life. I give it to them. Irina, Thurema, Frances. The Premices will remind me of Albert, and I will see Pussy at their home. Pain and emptiness—naturally my health is bad.

SEPTEMBER 9, 1943, NEW YORK

After returning to New York, the activity calmed my anxiety.

Ideologically, what has crystallized is the relationship between romanticism and neurosis. I have seen their connection. The result of romanticism is death. I have repudiated it, but I had not seen that it was synonymous with neurosis. Frances pointed the way to Denis de Rougemont’s Passion and Society, which analyzes the myth of Tristan and Iseult. This theme has appeared in all my relations except with Hugo, though my attitude towards Hugo was romantic and a rejection of happiness for the sake of intensity and passion.

The whole theme of my Southampton lamentations was, “I cannot live without passion!”

Passion and suffering, obstruction, frustration, and death—I see the relationship better now because of the myth images and de Rougemont’s cruel exposure of it.

This is no petty experience I have lived through. It is directly related to war, the cause of war. The relationship was exposed in the heroic defense of Stalingrad: the passion, heroism, death, but the gift of the self—selflessness—reaches the infinite.

I have waited to make this gift. I wanted to give up the personal war of touching the infinite and to die for Russia, to share in the intensification which its drama brings. That is clear.

Now, I don’t know what I’m going to do with the great erotic tumult in me. I cannot disown the erotic seeking a personal outlet.

“Write!” says Frances. “What marvelous writing you will do.”

I saw Jaeger, and for the first time derived no comfort from the analysis. There is an impasse.

I have no desire to write or to print my stories. I move automatically but soullessly. I see Eduardo. I plan for the printing. I fix the apartment. I attend to my clothes.

SEPTEMBER 10, 1943

Talked to Eduardo about my big, objective work to come, the one I wanted to start at fifty. I said to him I may take myself out of it completely and have everyone in it but myself!

He was enthusiastic. I said I would break all the taboos, expose all the myths, and end by being not the poet, but the supremely lucid revolutionary analyst preparing new myths of Valentina, the woman captain. Eduardo was excited.

But I ended by saying: “But first of all I want a lover. I won’t work until I get a lover. I will not sacrifice my body nor the life of my body.”

Five-thirty in the evening. I have returned from Dr. Lopez. There is a cyst on the ovary which is infecting me. No lovemaking for two weeks. Treatments, perhaps an operation. I took the news well. I am calmer since I saw Jaeger. No anxiety.

I do not intend to sacrifice my erotic life at all. I will overcome this.

SEPTEMBER 13, 1943

My weekend with Irina

my mother—Wassermann’s Ganna

Ganna

hysteria, will, tyranny—

Certainty that I am the myth maker

I have to turn everything into a myth, symbol, legend

Plus grand de nature

therefore I shall never deal with actuality as it is

nor do journalistic writing like Irina’s—

Satisfied with my lot. Irina maliciously situates me with the dreamers.

That’s a way of

embalming me

disposing of me.

But I don’t know that I shall always remain in the rarefied spheres of the dream.

the dream of pyschoanalysis

the dream of Henry

the dream of Gonzalo

the dream of communism

“Come down from your stratosphere,” says Irina, at the same time feeling a great uneasiness at my adventures, fearing and respecting me, not daring to reject my work merely as perverse, pornographic, or experimental.

I have a vague hunch, a feeling something is going to come of my honest struggles, sincerity, courage, and of my sacrifices.

SEPTEMBER 14, 1943

I cannot begin a work casually. I have a concept of something big. I cannot begin, select, eliminate. I feel whatever I do will have to be all-encompassing.

What happens if I leave myself out? Then everyone will be restored to his natural value, not mythical, not romantic, not enlarged, not symbolic.

With me absent and only the other characters present, it shall be in a human world, purely of feeling. Possibly if I eliminated myself as representing the legend, the vision, the far-reaching and the cosmic, I might get into direct contact with the natural aspect of human beings. It is only in relation to me that they become “poeticized” or translated into a dream. It will be a diminished world. A natural world, not an intensified one. With me absent, passion and intensity will be removed, as will the mirror reflecting people’s potential selves. It might be a way into the human. If I am there it will be mystical and mythical.

It might be good to begin writing about characters as unrelated to me.

For example, I see a bigger Ganna to be portrayed, the impossible woman, my mother, the extension of her. In a state of destructive revolution, the black anima.

If I disappeared as a character and became merely the vision, if I disappeared as an ego and used myself as the chemical which brought certain elements to light, I might accomplish the objective work of human dimensions which could relate me to the present.

SEPTEMBER 16, 1943

Jaeger was pleased with the development in the creation, but not with my illnesses, which she attributes to the suffering at sexual privation (the pain in my ovary), nor at my dreams which still show traces of masochism. In life I am blocked, but not in anguish. When I returned to New York, I had to face the torment of Albert’s presence: here on this couch he took me, on this porch we talked holding each other, before this table we first felt the frenzy and fever, here we parted, here we kissed with a joy so intense it was painful, and then hearing about him from Josephine and Adele, “He is still in Mexico, trying to get a job.”

Yes, it is the moment of maturity when “one has to rectify the errors by the imagination.” It is the moment of philosophy, but for me it is like trying to tame a tigress: the capacity for madness, frenzy and fever are still there, surging powerfully at a piece of music, a scene in the movies, unused, misplaced. Out of place with Gonzalo, certainly.

My Major Work occupies my mind. I didn’t want to give myself to it, to be possessed by it. But life and love are fatally denied me—I wanted to do it later. Now is the time for pleasure and sensuality, but I cannot reach them. I admit to an external obstruction (as I know the inner obstruction was removed): the fatality of Albert in danger of being drafted and forced to leave, the war keeping me in America, the desert.

SEPTEMBER 17, 1943

Forward again, accepting Gonzalo as he is, taking care of him, repainting the furniture and windows, restoring my clothes, recapturing my elegance, having a suit made out of Hugo’s dress suit, very smart. I am planning to print the stories with Gonzalo, to go to fiestas, dances, Harlem, to see Carl Offord, Richard Wright, the Premices. I am ruminating my Major Work because the mind is best occupied with this artistic construction than with the past. Refreshing, re-lacquering, remodeling the old.

So here I am, wearing a sienna-colored corduroy suit given to me by Thurema, Mexican sandals. My hair has been newly curled. Lopez says I’m much better. The economic pressure is lifting. Hugo is making a little extra money. The anxiety and strain are gone.

Voilà. Courage!

SEPTEMBER 21, 1943

Last night, when I did not expect it (for I have given up Gonzalo as a lover), he took me completely and with vigor. But I could not respond. Too much anxiety and repression and control have made me cold. What a tragic see-saw!

After seeing Martha:

Don Quixote

Idealization of myself

Henry

Gonzalo

Now I see my Shadow Self in the women I have liked:

June

Thurema

Irina

Here is the dark part of Anaïs.

I have never faced darkness except in those I love, and then only for combat. The enemy is within.

Let us find the dark Anaïs now.

Jaeger points out the inevitable suffering caused by idealization, dreaming, mirages, illusions. There is no happiness possible while I am dreaming.

The firefish falls into the dark unconscious where it must seek to live. The orgueil peacock falls too. Jaeger said: “I thought the other day when you came with the fuchsia bird in your hair how good a symbol it was of you. How it represented you. The colored plumage…”

Jaeger can only see my love for Henry and Gonzalo as not loves, but mirages, drugs and poisons. That was why life with Henry in New York destroyed my dream. That was why I sustained this dream by isolating him.

This return to true vision modified by experience draws me closer to Hugo, who alone withstands reality, whose character has become what I truly love.

Jaeger has been concerned with my elusiveness. Everything I have placed outside of myself, in others, but it all issues from me. My “shadow” self, my dark self, is in the women (except Frances) and in Henry and Gonzalo. Jaeger says I must find the shadow in myself, not its projection in others. It is like a detective story. I am so fearful of my capacity for transformation and illusion that I begged Jaeger not to let me escape again. I have had courage to suffer masochistically, but not to face the reason for this suffering. I have never accepted the shadow, but I have fought it in myself. I fought sickness, dark experiences, yet submitted to them at the hands of others.

Tonight I feel like Don Quixote, struggling for sanity. Symbolically, I fell in love with a coat, a coat that represents the great change in me. It is not the coat of the firefish or peacock... It is a very beautiful material, masculine tailoring, fitted, with a velvet collar and cuffs. It is expensive, aristocratic, simple, very pure, for action, and far from mirages of Byzance or the dream! I shall wear it a long time. It is enduring, of good quality. I chose it boldly, in an expensive shop, but I hesitated because of the high price. Hugo then insisted I should make him feel like a man of power who is able to get such a coat for his wife, and when I saw it was a symbol for him too, I yielded. It is a coat for a new life, and it will go with the very smart suit made out of Hugo’s fine English tuxedo. So I am fully blown Harper’s Bazaar elegance and out of the masochism of clothes.

I cannot write a book now. I am just barely awakening from a dream, and I am not wholly awake yet. When I am awake, I write the Birth story. I always feared awakening and what I should find.

I beg Jaeger to hold on, that I don’t know how to seize the dark Anaïs once and for all. She eludes detection. She is clever and artful at deceit and enchantments. Already I begin to feel that I have had enough analysis and that I can abandon it now and live and write, but I say this when I am on the threshold of the ultimate discovery of the dark Anaïs.

Idealization is the rejection of darkness.

SEPTEMBER 22, 1943

Last night when Hugo, according to ritual, sat next to the bathtub while I took my bath, dried me off with the towel, and then asked me to “put something nice on,” I wore the black lace nightgown. Then, because I had been concentrating my roving, far-fetched, capricious fantasies on Hugo, on my love for him, I was not only able to control the straining of my imagination towards the romantic lover, but by saying to myself: here I have happiness, a love that is happy and complete, and I transported myself into the present in order to enjoy it. I found myself relaxed, not full of resistance, and natural, as if Hugo were simply one of the lovers, and I would have responded if he were not so swift. But progress has been made, consciously and voluntarily, towards reshaping a perverse desire, an imagination and a body wanting always what it cannot have, rejecting happiness, always seeking the impossible.

It was while showing Hugo my coat last night that I realized it was Captain Valentina’s coat—it is the uniform, the rectitude, the sobriety, the disciplined!

SEPTEMBER 24, 1943

Ever since I started to track down my shadow it eludes me.

I note the characteristics of the women I was attracted to:

June: hysteria, unrestrained, unconscious aggression, sensation, sensuality, possessiveness, jealousy, fear, energy.

Thurema: violence, hysteria, unconscious behavior, emotionalism, extremes, action, energy in reality.

Irina: violence, hysteria, unconscious behavior, action, energy, actuality, reality.

But that applies equally to Henry and Gonzalo: Gonzalo was exactly like June and Henry like Thurema.

I know all this, but it does not reveal my shadow. All I have felt is relief and pleasure at their reality, their sensational and violent adventures, but I have not liked their behavior, could always see its destructiveness and fought it, never yielded to it.

It was the unconscious, loose and uncontrolled, that attracted me, the action, the drama and reality of their acts.

I felt enclosed and bound to my idealistic behavior, not free to act as they did, but compelled to be noble and selfless.

I like their naturalness. As Rank used to say, “Women like the bad man because he is natural, closer to nature.”

Closer to nature.

I began so far from nature, so ideally, that I wanted it, but found it to be mostly black.

My nature has been idealized and denatured. My fight with nature was also an expression of love, a desire to instill my spirituality in it—for I influenced them all, and I fought them—I did not yield to them.

The first time nature appeared to me as beneficial and innocent, it was in Albert. It was nature, naturalism, that I liked in Henry, his enjoyment. It was the savage in him I liked, in Gonzalo too. They are all violent like nature, unpredictable, capricious, stormy, wayward, emotional. But they are also sick, all of them, except Albert. That is as far as I can go.

Evening

This morning I went to Martha, and instead of talking I showed her what I had written since our last talk. I watched her face, with its wonderful expressions of compassion, indulgence, humor, forgiveness, understanding.

She said, “Your expression of all this is marvelous, crystal clear.” Her face was full of admiration. I felt it and was elated. Her praise, more than anyone else’s, has such significance for me! “You will have much to contribute to the development of woman. I feel that it was a privilege for me to analyze you, read you, that you gave me rich material, that this was a collaboration towards woman’s problems. Because you live so deeply and suffered so much, these experiences will mean a great deal to other women.” More than her words, her tone moved me. I felt like a starved person receiving manna. The tears came to my eyes. This obscure labor, so overlooked by the world, so little recognition or understanding of what I am doing, the silence around my writing. “Because,” said Martha, “you write straight from the unconscious.”

Her response was invaluable to me as artist, as woman. I was suddenly glad of all the suffering which opened such deep worlds to me. I was glad it was Martha who saved me when the suffering crucified me. I am glad it was she who gave me back my strength, because her vision reaches very far and is the kind I believe in.

The miracle now is one of synthesis. Martha made me fuse, integrate, synthesize. There is no doubt that all this flowering and renewal came from her. Without her this summer, I was dead. Now I am full of strength.

She smiled about the coat. Yes, it is for simple, direct action. It wasn’t hatred, jealousy, or temper I was concerned with in the primitives, but the energy, dynamism, the passion being used for life, for actuality, for the present. Passions make us act in the present. That was what I wanted. Mysticism gives us a larger vision, but the human dynamism must be there. Passion pushes the sails and creates the currents of drama and life and action. I feel ready for this.

I told Martha that because I had meditated on my shadow, only now do I see, because it was linked with my illness, the underground activity, my indirect buried creation: the diary.

Now I must come out of it at last!

I didn’t see the direct relationship between the pursuit of the shadow and the immediate answering dream: the diary! The diary is my shadow. I knew even as a child I was putting into it the rages, hatreds, outbursts, venom and complaints I didn’t want to use on other people! Enclose the devil in its box, but there it is, immense and dark!

SEPTEMBER 25, 1943

I wish I could write the END of the diary and turn to the outside story.

The theme I am interested in is the development of woman. I would like to take June, Thurema, Irina, Lucia Cristofanetti, Frances, their childhoods, their backgrounds, their indirect actions, their underground lives, their lack of fulfillment. What has kept me focused on myself was first that I was good for all the experiences, as laboratory experiments, that I was a supple general subject! Secondly; I was all these women in myself, and therefore my story was the most complete one. I was a symbol, the figure that can contain many figures. But instead of creating a character, I can easily tell the same story in many women, divide myself:

Irina: the masculine me writing novels, chic femme du monde.

Thurema: the maternal me spending herself on all, the courageous me.

Frances: the dreaming me, the analytic me.

June: the sensational, the unconscious, dramatic me.

Lucia: the oriental harem, timid, childish me—what Henry used to call the Japanese wife of Lafcadio Hearn’s descriptions.

Jaeger: the healing, most highly protective, intuitive, guiding me.

And there you are…if I write about these women, it will be more human, more accessible. Now, can I efface myself, like the cathedral builders of old, to focus my vision on these women?

In these women there was, to begin with, strength, a strength which impelled June out of her orbit, Thurema out of her ordinary life, Frances out of her poor, arid background, Irina out of her home into international sophistication, Lucia out of her enclosed Syrian harem. A strength which made them choose instinctively not the man who would again master and withhold them from the use of this strength, but the weak, childish man upon whom they could use this strength as mother, husband, muse, and at the same time whom they could become what they themselves did not dare to be: June making Henry the writer because she felt creatively inadequate but wanted to be the character of his creation; Thurema living through her children and wanting to live out her musicianship through Joaquín; Lucia first wanting to be a painter and then turning this into making her husband Francesco the painter; Frances feeding Tom’s writing and developing him, rather than facing a man equal to her who would possess her. All these women eluded being possessed, being passive. They played the active role, thus suffering in love because by being the aggressor, they forfeited being courted and loved as other women are. They suffer in their femininity, suffer from the man who cannot fulfill their dream (as I suffered from Gonzalo not becoming the active heroic revolutionary).

The effect of this active role upon sexual life is the accentuation of the passivity of the man, his limitless taking, (June’s giving to Henry was continuous and selfless too). The disastrous effect of the strength—when misused, it results in possessiveness, in great sacrifices, all indirect routes to fulfillment.

These weak men represented not the masculinity of these women, but the weak, newborn consciousness of an active role in life which women obscurely feel but upon which they do not know how to act.

These women could not connect with the totally masculine man as we know him because such a man would endanger this obscure, barely born, active role they felt urged to seek, the role of the new woman. Such a man would insist on passivity which by now has grown irksome and impossible. The weak child-man, on the contrary, was the right one to develop this new strength with, but he left the woman, on the other hand, alone, without a real mate or guide, without the support or the protection of the real man. The real man is capable of playing the father role when necessary, and certainly the husband role, and the child-man has failed even in his role of lover. So woman was left with a child who did not grow up, who did not gain strength from her efforts as the real child does, but became weaker and weaker. What a penalty to pay for this new strength she felt, and what a misuse of it!

Confusion. This strength was meant to be used directly, to have its own fulfillment in activity, not to be used as a lever by weak men—but in women it became confused with the maternal instinct, so woman’s first act of strength was always to protect.

Confusion, too, when her activity became corrupted into rivalry with man who considered this activity of women as a challenge, danger, a competition. They often punished women by either overlooking or denying the existence of their femininity. Rivalry takes away the love.

There is confusion in woman who feels that she is only imitating man and often losing the man in this process, like an exchange which demands the surrender of femininity. Not at all! No femininity lost! Women’s passivity in life is not necessarily feminine or linked with sexual obedience. Man fears her development as an usurper and arrests her expansion, misinterpreting it as rivalry, not seeing that this arrested, enforced passivity negatively corners her perverted strength into nagging, the domination of the husband and children, imposing her will over them because it is an unfulfilled, thwarted will which cannot spend itself creatively, usefully and positively in concrete action. The concentration on the home, which receives the discharge of these “turned milk” breasts, the sourness and discontent accumulated from the slavish tasks, the lack of more expansive living and remuneration (woman does the same labor at home, but she does not earn money or feel free, and instead is dependent on the man and receives no recognition of her work).

Man says: How can I make love to a sniper?

But didn’t women receive love from killers without confusing the issue?

Men fear the activity as a sexual danger. How can one kiss a corporal into submission? But woman is not seeking power but rather the expression of the dynamism of the emotional life. Man’s expression of power as negation of the primitive and the emotions is not satisfying to her. (Note: I wouldn’t do as a character in the book anyway because I have Hugo—no tragic choice of man, a happy ending as it were!)

Now, this analogy between primitive woman seeking to become articulate, seeking to be given a right to act resembles the problem of the negro. Women have gone to the negro for sexual power because of the degeneration of the white man, but there was more than that which impelled her: the negro’s primitivism was the same as hers; the language of the emotions, lost to man (having become the capitalist, the analyst, the man of science), was the same.

Caresse, dedicated to love, turned to Canada for the “best lover of all.” Frances is sexually starved by her dry twig of a husband. Thurema is not satisfied with her husband’s “financial success.”

The problem of primitive races is in great closeness to the revolution of women.

SEPTEMBER 26, 1943

Dream: I get dressed for lovemaking with Charles Duits.

And of course he telephoned today, and we went together to the Premices. Lucas told marvelous stories, Josephine pétille like a spangle, Mother Premice gave me a head scarf. The atmosphere was warm and human, with stories of voodoo, magic, etc. Albert has a job in Mexico but has not written me. He has wisely submitted to reality and not sought the painful ecstasies which could destroy him. What would I do now if he wrote me? Today I would not rush so fast to impossible ecstasies for which one pays with one’s life, yet physically my body is being sacrificed and denied, and in my dreams I am full of erotic fever.

Today I saw Duits pale and mystically blue-eyed as the eternal poet who haunts me. I resisted him during the summer, but now he charms me, and I see how he charms the Haitians who look at him like a figure from a cathedral window…illuminé.

Yes, the light, Josephine, which leads one away from the present into the infinite, killing the body in its journey through space after the divine and impossible absolute. Because passion is a fire, one believes the being will be dissolved and welded to another, and by dissolution the union of elements will happen. But fire cannot make this marriage. It is not fire which makes it. Josephine’s fiery black eyes look at the five-pointed star eyes of Duits, at his pale face and curly hair. She does not see the body without power, the over-developed mind, the orgasms of the soul cheating the body of its orgasms, the marriages of intuition and spirit making marriage on earth impossible. The disembodied Duits, poète maudit, who all summer refused the sun and the sea and liked only the night, the dream… Josephine, beware, beware, Josephine and her sensual, lively curves, provocative, animated, full of electricity and fire and wit.

If Albert called me I would go, for that is life. This game of the imagination, the book, is only a poor substitute. I would live and be willing to die afterwards, cries the romantic! Perhaps fortunately for me Albert is natural and passive, not romantic.

SEPTEMBER 27, 1943

Half-awake, I murmured: It is a question of forgetting Albert. I felt the writing would help me to forget Albert.

At the same time I am conscious of a resistance to the writing as if it meant being possessed by the book and not wanting my passion to go into that, but into life. As if it were a choice. I see clearly the energy withdrawing from the sex into the imagination, and I refuse this substitution.

I also know I must do it because I am the only one who can, as a soldier knows he must fight, a priest knows he must serve. I am conscious of a role which was often behind my choices and acts, that of initiator and clarifier for others.

Consciously there is no such choice to be made. There is no life demand made on me which can contain this passion. This passion devours me, poisons me. It is right that it should go into creation.

It was being at the Premices’ and seeing Pussy which reawakened my suffering at the loss of Albert.

To work, Anaïs. Now the twelve windows are painted, the style is modern and spacious. The colors are ultramarine blue, magenta, turquoise, dark green, and violet. The furniture is repainted in violet. I have thrown away all the old, faded, worn, useless.

Great distinction between the talk of theories, concepts, analysis, and the primitives telling a story. Gonzalo tells me stories, which is one of his greatest charms, and yesterday Premice told us stories (it was by the telling of a story that he won me). I am finding the primitive Anaïs who made a god of her father, who wanted a husband who would tell her stories, who told herself stories, and who is about to tell herself a new one!

Stories, stories, the only enchantment possible, for when we begin to see our suffering as a story, we are saved. It was the balm of the primitives, the way of bringing enchantment to the life of terror.

My “procrastination” consists of having to have everything in order before I begin—the house, clothes, papers—to be free.

I see women, women, women, tragedy in women. I am touched by their plight. I think of their inarticulateness. May each one find herself in all these women and be helped. I have so much to say, but I want to do it with my craft, without intensity, without anxiety, without acceleration and rarefaction.

I am not writing for the elite, but for the confused ones. I would like to have the Encyclopædia Britannica. I need it now. I want facts and concrete images, earth, science, body. Everything made flesh, everything a story, everything animated and dramatized.

THEME

DRAMA

IS

THE MISUSE OF STRENGTH

It is the misuse of the dream—the dream is the image of what one is to be, to become, to do. The dream is to be used as a guide, as a prophecy, as a creative source.

Women are dreaming the dream of strength and mistaking it for man’s dream. Man has been woman’s only image of strength, her only ideal of strength. It is time for her creation.

SEPTEMBER 28, 1943

I put on my tuxedo suit, my black veil, and went to Jacobson. He, expressing fully his knowledge of my evolution, stopped dead and exclaimed in his vague, inarticulate, crude way, “Ah! Une dame!” Maturity. As an experiment I have asked him to give me again the same “strength” cure he gave me a year ago in October, at the beginning of this diary, a strength I misused psychically on the struggle with Henry and Gonzalo and collapsed in spite of it. I felt that now I could take this physical strength and turn it into creative action.

From there I met Caresse a block away from our meeting place. She watched me cross the street without recognizing me, spellbound by my elegance and then exclaimed: “You are…you are a grande dame, Anaïs. What a change. I saw you walking so firmly, carrying your head high…”

But I sail boldly and luminously until I meet Gonzalo, a sick Gonzalo who is defeated by his weaknesses…

Anaïs, there are no miracles. Your passion and your dream deceived you, drugged you, but in the end you chose to dream with impotent men.

Why do I suddenly lose all my joy?

What a potent awakener the diary is. As I get ready to leave it, I pay it a slight tribute. This should be the last volume. At forty, I enter a new maturity, stripped of my mirages, dreams and miracles, of my delusions, my illusions, and my heavy romantic sorrows. What awaits me is the expression of this strength in action. I am about to lay down my magician’s wand, my healer’s paraphernalia, and to confront the act, in writing as well as in living. Without the diary, the tortoise shell, houseboat, and escargot cover. No red velvet panoply over my head, no red carpet under my feet, no Japanese umbrellas growing on the hair, no stage settings, tricks, enchantments…

Hadn’t woman lived for centuries in a state of annihilation before man, dependent and incomplete? The few who had escaped this had suffered equally from deprivation, for man condemned them to sterility, solitude—the state of harem women—a passive infantilism, stunted growth, almost degeneration, for the flesh alone flowered on sweets and pillows.

That woman’s strength should have found no impersonal object, no labor to fasten to, was tragic for man, for it became as dangerous to him as the primitive’s strength.

Such women are not consumed by the man who could master them, the man so powerful that he can do his painting and music alone, but by the uncertain, vacillating child-man who arouses a devouring maternity with his weakness.

The giant mothers.

You cannot quench a woman’s strength with laws, curse it with solitude or abandon. It must be dealt with. It is the woman’s revolution, the flower of revolt and injustice. The men who lost their power as primitives are the prey of this woman. It is a kind of vengeance. There is something in it of the cutting of Samson’s hair. The nature of woman has not suffered the damages that man has in his struggle to suppress nature. She has not been as exposed to the social poisons. She has been relatively sheltered. Her power is unspent, new.

OCTOBER 1943

Because of objectivity, my vision has become like a pure diamond. I see into others’ beings so clearly that they seem transparent. Last night Josephine, Adele and I practiced our dancing. Duits was there, Duits the child teasing Josephine the child, and Duits the poet with the pale face fascinated by Anaïs, begging me to wear the glass slippers so he could look at my beautiful feet so extraordinarily naked. Josephine courted him with all the perfect sensuality of her strong body and her dancing. I did not court him, yet he dreams of me. Once again warmth invades me, an enfolding warmth, a yearning to open his delicacy and youth. I was astonished at how I could read all his feelings and his dreams, all of Josephine’s perplexed, puzzled emotions at this new species of animal who does not accept the contagion of his fire. At the same time I felt a strange taboo, not out of fear of suffering again, but like a religious mystic order of divination: I believed always that I saw more because I loved more, now I feel I see more because I see them all outside of my love. Of course, it is always with some kind of love that one sees, but what I feel now is a love not of Duits, but of all he represents in the long lineage of the poets I have known, in the hierarchy and dynasty of the poets. He the last pale flame of them all.

I see through his body into the bloodlessness. I destroy his legend because I see he is anemic, that he dreams of vampires and sucking blood because of his great need of it. I held his almost transparent hand in mine, light and fragile, and Josephine cried out, “My god, you have no flesh at all!”

A game takes place between reality and the dream. Josephine stretches out her strong black legs, and then prances like a well-bred horse, and Duits watches.

Then we sit in the semi-darkness, telling strange stories to each other. Duits’ imagination is nourished by the fairytales of the past, and he does not yet know that it must feed on life.

Thurema and Jimmy understand the diary because it is human—Winter of Artifice does not move them. If only I could find my human form, naturalness; if only the human Anaïs could speak now the same human language she speaks in the diary.

I still speak the language of the voyant, of analysis. I am learning from Josephine and the Haitians how to tell stories. I used to tell stories as a child, adventure stories. The great adventures of new unconscious revelations can be told with excitement. Jimmy says, “Why read fiction when you can read Anaïs?”

J’approche la fin du journal…la fin, la fin, la fin, la fin…

OCTOBER 3, 1943

Having gathered together the fevers, the conquests, the crusades, having pulled in the sails of my restless wandering ships, having garnered, ramassé, called back from the Tibetan deserts my roaming, fervent, mystical soul, having rescued my spirit from the web of the past, having cured myself of the drugs, poisons and perversions of romanticism, having surrendered the impossible dreams, having mastered the madness of my erotic desires, having called back into the hearth the weeping dreamer, the disconsolate idealist, the exhausted Don Quixote, the lamenting, exalted peak-seeker, the divagating nerves, the dissolved, the lost, the frenzied, the twisted, the tortured, having escaped the chambers of torture, the self-punishments, the holocausts, the pyres, having meditated on the present, focused on the present, I integrated. I gave Hugo today a whole woman who responded quietly but completely to his desire, who vibrated in the first orgasm of happiness…

A pale flame, after the consuming ardor of passion, but a pale flame that resembles the heaven I perceived now and then as possible through the darkness of my ordeals, prisons and infernos. I can truly say passion is an inferno, and this is felicity, and the body and soul rest in their moorings, the painful tensions are relieved, the anguish, the anxiety, the terrors, the repeated agonies… For the first time I am not ripped apart by restlessness; my imagination does not wander alone in the night, wailing and questing. For the first time body and soul are together inside the window, with the door truly closed over them, and I rest. The music I can bear; it is not an invitation, a provocation to a mad search of the world, a pursuit of ghosts, a desire for mirages, an embracing of a void, and this is no mere interlude to an unceasing pain and hunger, but a possession of the present in the person of Hugo who has, for twenty years, been the haven I did not want, the fulfillment I perversely negated, the patient image of love itself, unceasing and indefatigable, and eternal, and not passion, and passion is not the marriage but the illusion of union that never takes place. Hugo’s every word answers my word, his faith my faith, his constancy my dream of constancy, his concept of love my desire! For the first time I can close the window and say everything is here, everything is here where I wish to put it, in the present, on earth…let dreams and ecstasies no longer torment me. I was weakened and tormented by the magnitude of my desires. I could not fit myself to human proportions. The enlargement and magnifications were made at the cost of tearing the body and soul asunder, at the cost of insatiable fevers and the habit of drugs which caused indescribable pain after the first ecstasies.

It is only as I grow mature and whole that I finally recapture my childhood, and it is only when I grow mature sensually that I recapture my sensuality, which in both elements resembles the sensuality and the childlikeness of the Haitians.

Last night as we danced together and told stories together by the light of the red candles, I felt I had recaptured my true nature, like theirs, sensual and innocent, and my childhood’s power of telling, receiving and inventing stories. How strange that it is only when you mature and rid yourself of the false childishness, the false youth, and the false nature, that you recapture the true games of faith and desire…the wholeness.

Childhood: the bananier that moved in the night like a woman waving her arms, the mapou trees of evil walking about at night that terrified the Haitian children, the leaves one rubbed on one’s arm which caused swelling and saved one from school, the medicine a negro took too frequently, a poison which made him white like an albino, the reading in a glass of water, the eating of the glass, the voodoo magician who could place a lighted candle in the water without drowning its light…the childhood, my childhood, finding its stories and legends in my own rich life, eager to tell them and cause surprise, fear and joy in others.

My nature finds its climate among them because they touch each other so warmly, they kiss frequently, caress each other, make gifts to each other. There is warmth of life and sensuality.

Albert’s gift to me, Albert, so young, who gave me his wisdom—do not dream, Anaïs, you are dreaming me—who gave me his youth and his climate, his people to help me find my heaven, who guided me into paradise. Albert, the image in the flesh of Jaeger’s teachings—Jaeger my marvelous Guru, guiding me out of the inferno, Albert helping me to dance into a new earth.

So I have found the mobile mapou tree of the legends at the same time as my detoxification from fatal drugs, at the same time as the possibility of the happiness I sought, the human warmth and simplicity of reality.

I learn Josephine’s dances because they are Albert’s dances. I listen to stories because they are Albert’s stories. He, the dream of joy, giving me the island in which my human warmth has flowered.

So I can dream, dance, write, enjoy Hugo and the present. Tu n’es plus malade, Anaïs. A great shock split you asunder, but now you have welded the fragments together, and from this will issue your strength. And where are the jeux?

I found the only mature jeux possible—humor.

OCTOBER 6, 1943

I wrote my first four humorous pages about Thurema (on her cooking and on her clothes). I laughed while I wrote them, enjoyed writing for the first time.

OCTOBER 18, 1943

For many days I lived without my drug, my secret vice, my diary. And then I found this: that I could not bear the loneliness. That in writing the book about other women, there were still so many things I could not give to them, and above all, not one of these women could contain my obsession with the perfecting of my life, its completion. The last visit to Jaeger on this road of mystical development brought an extraordinary crystallization of all the experiences: I achieved integration; I gave myself to my fundamental love for Hugo—as a mistress; I gave myself to my home—I spent hours cleaning, painting, re-animating, renewing; I gave myself to an objective work. But I realized I did not want to write a book, I did not want to give anything. I wanted to be, merely to be, to enjoy the integration. So. In my new black suit I felt a new solidity. Suddenly the wanderlust ceased, the straining of an ever-departing ship. This part is comparable to opera glasses at first maladjusted, and then focused. I focused on Hugo, who changes and becomes always what I want, on my home, on what I have. Thus my vision, arranged for distance, saw the near. The near has become the marvelous. What I strained to abandon, to transcend, became wonderfully animated by my enjoyment. Fifth Avenue: the hustle, the luxury, the movement. Going to an exhibit where I touch people superficially enough so they cannot disturb me. (I never knew how to distinguish between what must be kept at a distance, the valueless, and what can be felt—I felt everything and suffered from nausea. This can no longer touch me.) Returning in the subway in the first car, and looking at the tunnel swallowing me, which I used to fear, caused me pleasure like a montagne Russe of darkness, red, green and blue lights. Everything reflects the inner change. The quietness.

Gonzalo does not know what has died. It is too subtle for him. We have moments of dreaming together, but they are nourished by a resplendent past, not by the present or by the future. They are reflections of a violent passion which was finally suffocated in his earthiness, in his weakness.

Hugo is free and strong, and wants what I want. With the relinquishing of the tension and the mad desires, came joy, the joy I craved for forty years from behind the prison bars of my tragic soul, always thinking it was not unattainable, that it was denied me. And it lay dormant, latent in me. Not necessarily in the South of France, or in Haiti, or with Albert, but in me, a deeply buried precious stone, like the diamond born of utter coal blackness!

So I tapped the source, and it flowed so easily.

One night at George Davis’s house, when we danced madly and humorously to Haitian records, I imitated Josephine’s trance dance and became entranced and frenzied to the drums…

With Hugo there is gayety.

With Hugo I never feel the loneliness I did with Henry and Gonzalo. There is a sense of nearness which no passion can create. The loneliness is lessened now that I have fewer secrets from Hugo, and he feels my return. It gives him a sense of power. He has been divinely patient because he dreams my dreams with me, forgets himself in his love, and now he is compensated. He won.

Talking to the diary was part of that loneliness, the necessary unburdening of so many secrets. Now I have fewer secrets, fewer burdens. But I still feel this is a wonderful story, and it would be a pity not to tell it.

It isn’t that I have forgotten Albert. Strangely, he is as vivid and alive in my feelings as when he was here. Only I do not suffer, I do not rebel, I do not hunger and crave uselessly. He is there. He is everywhere, bright, beautiful, desirable. I melt at the remembrance. I am filled with love. The love and desire are intact. They did not need to be killed for me to survive.

When pain cannot kill me, I am healthy. I can take the pain and transform it, take the pain the whole world is suffering and, without being closed to others’ suffering, experience pity and not die. I am not stopped and not murdered. The neurotic transforms pain into an attack of paralysis and cannot continue living. He is arrested, fixed upon one experience, as I was fixed upon Helba’s destructiveness. Psychoanalysis and Jaeger have given me something I never knew: happiness. It is like the difference between a body that has known only fever and when suddenly the fever ceases. The entire world has changed. It is health. People in the street look normal. I cease to feel anxiety and certain diabolical distortions. Before, 14th Street represented the New York I hated and rejected. Now it is merely 14th Street. It has nothing to do with me. I am stronger than my hatred, and it cannot possess me. 14th Street is where I walk, on a very beautiful autumn afternoon to buy gouache specter violet to finish painting my bookcase. It is the street where I buy veils with spangles for 39¢, which I use charmingly and seductively as other women use expensive $15 hats. It is a neutral street, it is not monstrous. Surely it symbolizes the ugliness of New York, but this ugliness cannot penetrate me. I am filled with other things. I must remember to cut four slices of the bread Gonzalo likes to eat with coffee at the press. I must write a letter to Eduardo, who is reliving The Good Earth in miniature. I mailed Henry’s paintings. I copied volume 64. I wrote Mother in Havana. I cleaned a lamp for Gonzalo. I stayed home alone one evening without feeling abandoned or lonely.

It is meaningful and important that there should be nothing in the house that is useless, cluttering, meaningless. Épurement, purification, simplification. Discard, throw away, give, rigorously. No déchets, no careless accumulations, no odds and ends, no unworn objects, only the essentials, the living, the basic.

Carnet de route: light baggage.

NOVEMBER 4, 1943

The euphoria of the analysis has worn away. I am no longer anxious, I am content, but I dream intensely (in place of writing in the diary?), and I am tired.

But we did the first page Under a Glass Bell today.

NOVEMBER 11, 1943

New development due to analysis: I fight for my rights instead of being passive and hurt. I have a good relationship with Thorvald. Greater firmness. Action.

Very ill at night with ovarian pains.

NOVEMBER 16, 1943

Important decision. I wanted to do something for the world, for communism, for the negro. Should I join the Party? Gonzalo says no because: 1. I show no aptitude for the science, detail and labor of political work, no professional interest in its routine. That is true. 2. I am not properly educated in the theories of communism, have never studied it thoroughly, and I show no sign of real knowledge. That is also true, but it is true about everything I do—I have never studied or labored or worked on the details of writing. I have marvelous ideas about costume, but I cannot sew anything. I have fine ideas for the house, but I’m slap-dash in their execution. I hate technique, applied science. Without Gonzalo I am not a good printer because I can’t understand measurements. Am I to forever accept this as a defect of temperament? Am I always going to rely on my talent, inspiration, intuition, improvisation and inventiveness? Am I never going to discipline myself? I thought the Party would discipline me, but Gonzalo says no, that is a false effort. But then where can I begin? I want to act. Gonzalo says: “In communism there is no action without theory. Study first of all. Go to the Worker’s School. Then you’ll be able to act.”

So at last I face my lack of action as due to my lack of technical, practical application.

Fine. I have made a good start on the science of writing. Printing made me more careful, tighter, more concrete. Now for politics, the applied arts, crafts, and sciences. I will learn to sew. All this bores me, has always bored me. Let us see.

I never knew anything about psychoanalysis, nothing about painting. Everything in me comes from a kind of genius, but I feel this cannot go on. It’s like a mystic existence without body. I am always conscious of trying to grasp the meaning, the mystic meaning, but not the body, not the body in action.

This is the book of Action.

NOVEMBER 19, 1943

During the night of ovarian pain, before falling asleep, I was in a very bad mental state. First of all I thought the pain came from a tumor, or cancer, and then I saw myself in the hospital and getting pity. I was glad to worry Gonzalo, but I remembered Helba had her ovaries taken out and thought this would happen to me. I remembered the child had a tumor and felt it was caused by the abortion manipulations.

Strangely, the next day Lopez, who is very thorough, explained that I suffered from a painful ovulation which happens between periods, the egg maturing and ready for pregnancy and being ejected and bursting from its shell, sometimes causing pain.

I have made an unnatural effort to stand on my own feet, not to see Jaeger again. I liked the ideal of a clean finish, no threads hanging, like a perfect story.

NOVEMBER 24, 1943

My happiness with Hugo, based on harmony, is increasing. My health is mediocre and a source of continuous small torments, but I feel strong, and I want action, action!

In public I enjoy the audible cult of my appearance, enjoy creating a stir, even though I dress very simply. Incurable Anaïs, who feels reassured by others’ praise!

The whole duality lies between what is dreamed and what is actualized. The dreaming produces anxiety because it is ghostly, evanescent, unstable, fluid, but above all because it is lonely. No dream is shared.

Reality is shared and similar (people’s dreams can be similar, but they cannot create a human relationship), and the similarities of human experience—war, birth, death, suffering—draw people together. As I come closer to reality, I feel greater strength and greater companionship.

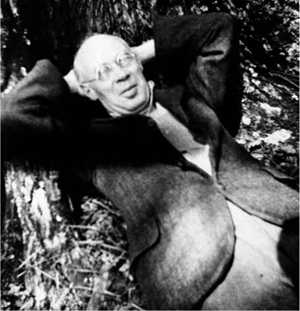

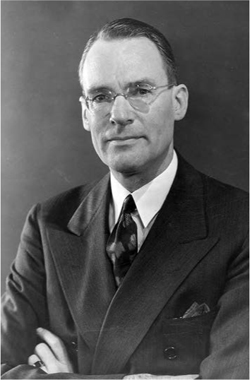

Anaïs Nin, 1940s

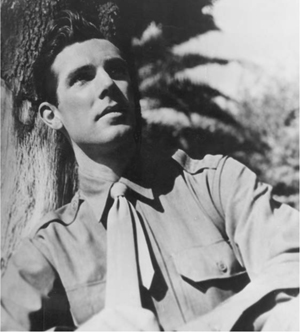

Henry Miller at Hampton Manor

John Dudley at Hampton Manor

Anaïs Nin at Provincetown

Edward Graeffe

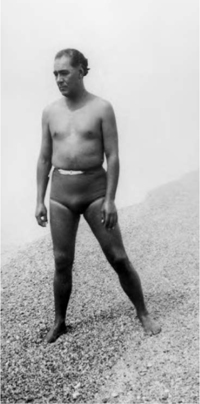

Gonzalo Moré at Provincetown

Anaïs Nin at her press

Albert Mangones

Publicity photo for Under a Glass Bell

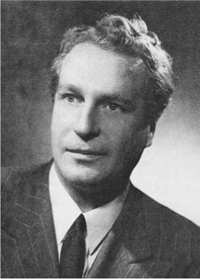

Hugh Guiler (Hugo)

Valentina Orlikova

Anaïs Nin in her “action” coat

Publicity photo for This Hunger

Anaïs Nin with some of her “children”

Gore Vidal

Anaïs Nin and Gore Vidal

Rupert Pole