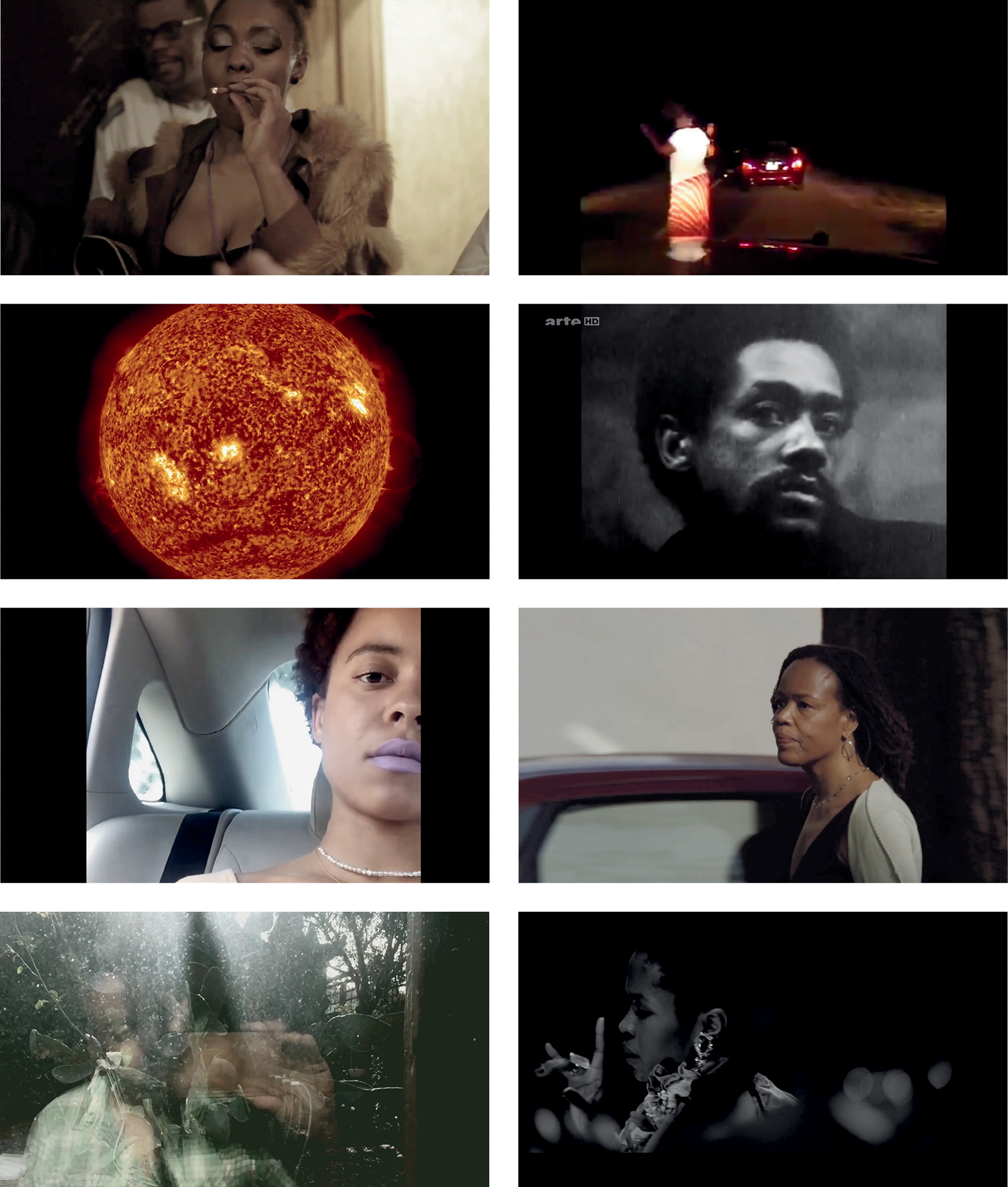

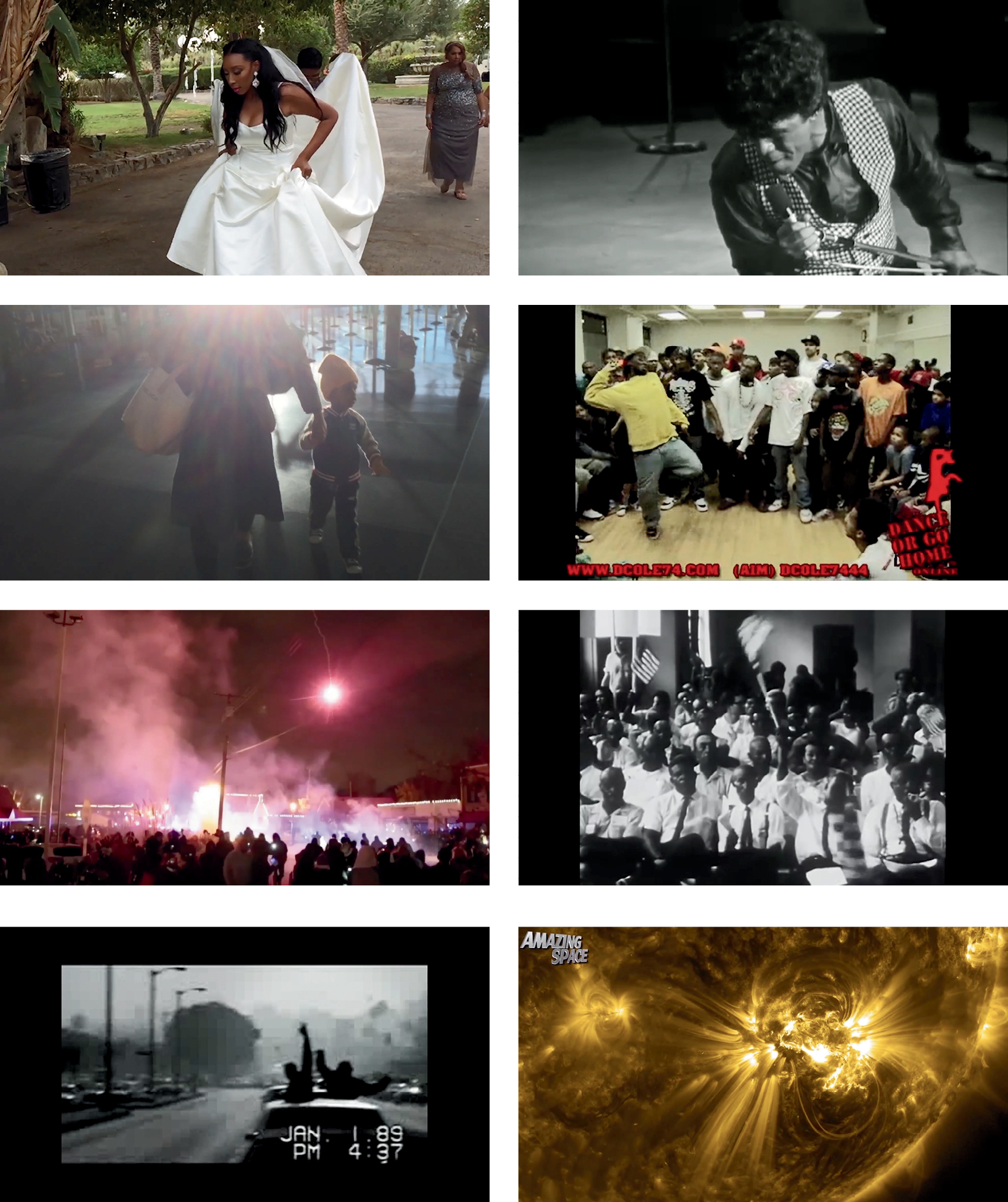

ALL IMAGES:

Arthur Jafa

Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, 2016

Single-channel video (color, sound)

Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York/Rome

LOVE IS THE MESSAGE, THE MESSAGE IS DEATH

ARTHUR JAFA IN CONVERSATION WITH TINA CAMPT

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity. It took place in December 2016.

|

I’m gonna start off with one of the things that’s really been troubling me about it. This is my own hangup for sure. A lot of people have come up to me and said, oh yeah, I’m really moved by [it], you know. I remember when I was putting it together, I actually was crying when I was editing the first pass of it. We put it together very, very quickly. We put this together in basically two or three hours. I remember crying when I was putting it together, and then I put it away for a few days. Then I added a few shots and that’s the last time I remember feeling anything intensely about it. I’ve been really struck by the degree to which I don’t feel anything when I see it. Which is striking to me. The last time I really felt anything strongly [about it] was when I saw it was at the opening because it was the first time I had seen it with a lot of people. I found myself standing next to people and channeling their feelings. On some level, I kicked into this place of kind of disconnectedness from it. So I’ve been really struck by that sort of disjunction between that and how a lot of people have been reacting to that piece. [I] want to talk specifically about some of Tina’s ideas about listening to images and how images affect a viewer and how they can affect a viewer. |

|

|

Tina Campt: |

I first encountered Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death on my computer as a clip that was sent to me by a friend. I have seen it about fifteen, twenty times. I would watch Love Is The Message over and over on my screen and I would find myself positioning myself backward and forward, closer to or farther away from the screen. I was not trying to see the photos, the images, more closely. The relationship [was] that I was trying to get the impact of the images and I needed to get that impact physically by way of the sound that you used to animate the bodies in it. We were talking earlier today about the difference or the relationship between movement and motion. We think of those two things as synonyms but they’re not. Movement means “change in position of an object in relation to a fixed point in space.” Motion, on the other hand, is a “change of location or position of an object with respect to time.” One of the things that Love Is The Message is provoking us to do [is examine] our relationship to images at a certain velocity over time. Where are the bodies moving? How do you see the choreography of bodies in violence through music? To open yourself up to a different sensory experience of this film or to a different sensory experience of these images means not just to watch them move across the screen and try to read what they are telling you but to actually put yourself in physical proximity to them. I think that physical proximity is through the sonic penetration…the way in which the music and the actual sound of it is what is actually connecting us to the images. |

I wanna figure out how to make a Black cinema that has the power, beauty, and alienation of Black music.

ALL IMAGES:

Arthur Jafa

Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, 2016

Single-channel video (color, sound)

Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York/Rome

|

I wanna figure out how to make a Black cinema that has the power, beauty, and alienation of Black music. |

|

|

Campt: |

Tell me, tell us what you mean. |

|

Jafa: |

One of the things I realized very early on, though, was the way in which this whole idea of Black cinema was being defined at the time [I was a film student at Howard] was somewhat narrow in the sense that it was a binary. They would say like, “Okay, what’s Black film? It’s not Hollywood or it’s ‘against Hollywood’ ” so that’s a fairly radical idea when you’re first confronted with it. We were like, “If Hollywood has narratives, does that mean Black film is necessarily like, non-narrative?” If Hollywood films are in color does that mean, you know, Black films have to be in black and white? We increasingly started to think, “Well, what would a real Black cinema be and how might we kind of define it now?” I’m still teasing out and trying to implement—fully implement—this idea of Black visual intonation. I realized at the core why Black music was powerful was the Black voice. You would never confuse Billie Holiday with Fela [Kuti] with Bob Marley with Charlie Parker or with Miles Davis, right? How do we understand these traditions or continuities of manipulating tonalities in a sense? We’re the illegitimate prodigy of the West and we came to the Americas with this deep reservoir of culture of expressivity. There’s a great quote by Nam June Paik, who is generally considered the godfather of video art, that said the culture that’s gonna survive the future is the culture that you can carry around in your head. I saw the Middle Passage, in particular in terms of Black Americans, as a great example of that because the places where Black people are strong tend to be in those spaces where the cultural traditions can be carried on our nervous systems. |

|

Campt: |

In this piece, the motion of bodies is really crucial and it has to do with what we were talking about earlier of the relationship of Black people to spatial navigation, right? There’s bodies in movement in violence, bodies in motion through dance, which is not always choreography—it’s a relationship to rhythm or music. And then bodies in motion through athleticism. You’ve got Muhammad Ali, you’ve got the basketball, you’ve got the fans around the basketball court who are synchronizing with the people on the floor. One of the ways in which you understand Black people is through people’s capacity to navigate space and trajectory. |

|

Jafa: |

Music is a great place to actually think through ideas because you can also share those ideas with people because people, particularly Black folks, we know all of the music. I mean, we know everything that anybody’s ever made. We tend to be able to sing all the songs. Even if we don’t know the words we know the trajectories or the inflections and things like that. When Black people dance, what’s going on, on a phenomenological level, what’s going on? I came up with this idea that, in terms of the two things—Black Americans are acutely sensitive to rhythm. Most people would acknowledge that Black Americans, Black people from most places, right, have an acute sensitivity to rhythms. |

|

There’s something to be said for making just explicit what is often times implicit—which is Black people [are] just killed like we’re not human beings. How do you put something in a space in the way it can cut through the noise, in a sense? There’s ambiguity about [the] appropriateness of having an image of a man being murdered like this. First of all, this footage is all over the place. It’s everywhere. It’s not like we’re digging stuff out of archives that nobody’s seen. It’s literally everywhere. The question to me became, how do you situate this footage in a way so that people actually see it? How do you actually make people see it? Simultaneously—there’s something to be said about [the] ability to be able to see beauty everywhere. It’s something that Black people have developed. We’ve actually learned how to not just imbue moments with joy but to see beauty in places where beauty doesn’t necessarily exist. Now, the thing about this shot [is that] it’s a brutal example [of] what happens to Black people here. It’s also an incredibly beautiful shot. |

|

|

Campt: |

One of the things that I kept thinking about during this film is what you’re asking us about empathy and the way you’re focused on that eye. |

|

Jafa: |

I’m very much preoccupied with how the work that I do, at base, is always trying to expand narrow notions of who we are, who is we, you know, who identifies with what. Who can identify with what. This whole idea of empathy being learned. People of color have better empathy in cinema because they go to cinema all the time where they see figures who don’t look anything like them. And they have to have the capacity to project themselves into that space and empathetically take that experience. You know, we need more cinema because we need more spaces for more types of people to be able to exercise that empathy. It’s one of the reasons I’m not interested in making films with white folks. I’m really interested in making work that always is foregrounding Black people’s humanity, even when they’re bad guys or good guys. |

JAFA, CAMPT