It probably doesn’t come as a big surprise that individuals and families who are suffering from problems with anger may share many of the same dynamics with other families in which violence occurs. Anger can manifest itself as abuse against one’s partner or one’s children. It may take the form of verbal or mental abuse or neglect or may segue into the realm of physical or sexual violence. In the United States, the incidents of violence that occur against a spouse, boyfriend, former boyfriend, girlfriend, or former girlfriend are estimated to range from a little under one million to three million each year. Violence is certainly not uncommon, but just because there are anger problems, doesn’t mean that violence will always follow. However, both violent and nonviolent families may have a few dynamics in common.

So it can be helpful in understanding and overcoming your anger for you to explore how the two situations are connected and why this may be the case. Anger, rage, and ultimately violence are all part of a continuum of behavior. This behavior can range anywhere from the threatening glower or the angry word, to actual physical assault or assault with a deadly weapon. It’s all a matter of degree. The question is, how do these behaviors relate to one another and how did these behaviors come about to begin with?

Down Through the Ages—A Quick Trip Through Time

Violence has been around for as long as humankind has been in existence. Perhaps you remember our cave guy and all the ideas he came up with for protecting his cave family and keeping them in line? Power and control have been important dynamics for most societies from the get go and, no doubt, the use of threatening behaviors, coercion, and violence helped things along. They helped get the message across about who had the power and provided a nice setup for punitive action if someone didn’t happen to agree. All these behaviors had to do, once again, with social learning theory.

Even in the earliest times and even in the female-controlled matrilineal societies, violence was used at least in ritual form. In many of the early Indo-European agricultural societies, a male would be chosen as the representative of a god, a corn-god perhaps. Or perhaps he would represent some other potent deity. He would be wined and dined, entertained big time by the queen, and pampered by the tribe, and at the end of his appointed term as “the god,” he would be ritually sacrificed. He would be slaughtered as a means of demonstrating obeisance to the earth goddess in order to bring about the earth’s fertility.

Later, as the guys took over and more patriarchal societies began to develop, women took on the more subordinate role. They were considered to be a man’s property and were, therefore, easily disposed of. In many societies they accompanied their husbands to the afterworld, kicking and screaming maybe, but, hey, it was the way things were done. Whether it was on a burning boat or some other type of pyre really didn’t matter much—they were still goners. The strong dominated the weak, and aggression, power, and control were, after all, the tenets upon which the world operated.

Obviously, the idea of people as property has been with us down through the years and has revealed itself under many different guises. The application of the principle can be applied not only to the “battle of the sexes,” but also to other groups as well. Entire civilizations sought to dominate less favored ones. Proponents of different religions sought to overcome whoever was considered to be “heathen” of the day. These themes occur over and over throughout history and are, quite obviously, still occurring today. People have always wanted to dominate others for reasons that are religious, political, territorial, and cultural, or by some other motives or unidentified needs. The fact remains that, within the family, someone’s need to dominate, to control, or to overpower can lead to big problems.

A Good Rule of Thumb and Other Big Ideas

Have you ever heard the expression “That’s a good rule of thumb”? It’s an expression that comes down to us from English common law. This law conferred upon a husband a legal right to keep his wife in line. He was encouraged—even admonished—to use a rod on her in order to correct any “wrong” behavior. The only stipulation was that he could use a rod no thicker than his thumb for this purpose. Pity the woman whose hubby had really big hands. Men with small thumbs were probably much sought after as husband material in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries!

Time moved on and what went on behind closed doors remained the personal business of the family. Power and control continued to be the mainstay of most Western societies. The Spanish Inquisition and the Salem witch trials inflicted pain and suffering on anybody who didn’t fit in with the status quo. Various countries who engaged in empire-building schemes, and a plethora of territorial and religious wars, saw to it that the doctrine of “might makes right” continued to flourish. Darwin showed up in the nineteenth century and told us all about that cool concept “the survival of the fittest.” The ball just kept on rolling.

The Twenty-First Century Update

Although without doubt wars were, and of course still are, in vogue, in the beginning of the twentieth century questions began to arise as to the legitimacy of using power tactics within the family. It was considered to be the norm in most families for Dad to be the boss. Dad was top dog, and then came Mom. Marriage ceremonies, many Christian ones anyway, had set it up, after all, so the woman agreed to love, honor and obey her husband. The kids were at the bottom of the heap with even less say than Mom. It was pretty much an accepted fact that Dad was king of the castle. Most families were not democracies. But certain other segments of the population had begun to wonder about whether this plan was the best way of running the system.

Suffragettes were on the move, and The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals started taking a look at animal welfare. Society was beginning to think about providing children with some rights and protections of their own with the development of child labor laws. Things were beginning to change very gradually. Finally, in the 1960s child abuse laws were passed—and American society finally caught up with the SPCA.

Pop culture continued to expose us to a confusing set of ideas in the 1950s. It’s still doing so today in the twenty-first century. Mixed-up messages about acceptable behavior were dished up in movies and in music then and now. On the one hand was (and still is) the romantic ideal. On the other hand was (and still is) a blithe acceptance of the message that violence in the family is acceptable.

Movies and TV can provide us with several examples of these types of confusing messages. Remember those old John Wayne movies where his character was as likely to give Maureen O’Sullivan a swat on the bottom as he was to give her a wet smooch on the mouth? Or how about the oldies in which the male character, after receiving a big slap across the face, takes the leading lady in his arms and smothers her with kisses. Now that last example may not sound like much. So what? You say. Hey, it was the Duke after all. He was just horsing around; all the extras in the movie thought it funny. O’Sullivan was being a brat: She deserved the spanking. Or, so what if a woman slaps a man. He’s a guy, a big guy, and she’s like a little fly—it’s not going to hurt him.

Well maybe you know the difference, but where does it stop? Where do you draw the line between innocent fun and provocative behavior? Is physical abuse ever really justified? Doesn’t it follow that if it’s okay for me to use violence or to yell and scream, it must also be okay for you to do the same thing? If you follow that line of thinking, then how do you decide when enough is enough? What in the world was the message that we received from these juxtapositions of behavior supposed to be? And now, shows like Alias and The Sopranos send us the message that—what?— the family that slays together stays together? I guess so. Even some of the video games our young people buy demonstrate an appalling acceptance of violence and domination through power control.

I’ve asked people who have physically abused their children how they would feel if somebody twenty feet tall and 1,200 pounds took a switch to their back (or bottom, or side). I’ve yet to get an answer. Certainly it’s all a matter of degree. Using violence, except in the case of self-defense, is simply not acceptable: It leads to only more violence.

One of the largest national violence surveys ever conducted found that in almost half of all violent episodes, women struck the first blow. Albeit, often a wimpy one by a man’s standards, it was apparently in many cases enough of a provocation for the abusive situation to escalate. Men are bigger than women—most of the time. They are also responsible for seven times the serious damage to their partner. Women are catching up though. They are beginning to use weapons to retaliate.

The shelter movement of the 1970s began to draw attention to the problem of family violence, and the closed door began to open a crack. Researchers started to take a look at what was going on inside families. They came up with several ideas about how violence developed, along with its baby brother, illegitimate power and control. Several theories have been put forth, and I’ll talk about seven of the most prominent ones here.

Social Leaning Theory

You remember, monkey see, monkey do? Many families who operate with dysfunctional rules are closed down families with rigid self-sustaining boundary rules. Perhaps that’s what made The Addams Family such a silly show. They operated with outrageous rules, but they also operated in an open relationship with society—they were right out there—but in the show anyway, nobody seemed to think the family was that wacky! Everybody took the family’s weirdness in stride.

In the real world, on the other hand, dysfunctional families, then and now, keep their secrets to themselves. They don’t receive any reality checks from the outside that they can compare with their own behavior and problem-solving strategies. Dysfunctional families don’t want these checks or strategies. They may be operating with lousy systems, but they are systems the family understands, with rules they know, and it’s their rules. And until rather recently, if an outsider did happen to stumble upon something not quite right that was going on in somebody else’s family, that outsider seemed almost embarrassed to have intruded and to have found out about it. Frequently, when the outside party colluded with the dysfunctional family, that person decided to mind his or her own business and rarely went further with any type of intervention. It still happens. Have you ever seen a parent beating on a child in a store? How did you feel about reporting it? People are afraid to get involved.

Again, the very powerful dynamics that can make family loyalty so strong can also keep an impermeable lid on family problems. As with other types of behavior, violence and power and control tactics are readily learned in one’s birth family. Children who see anger tactics used in their families of origin will grow up using anger tactics or become the mate of someone who uses them. Why? Because for them it’s a familiar way of settling disputes. As well, children who see violence or are treated violently are much more likely to become victims or perpetrators of violence when they become adults.

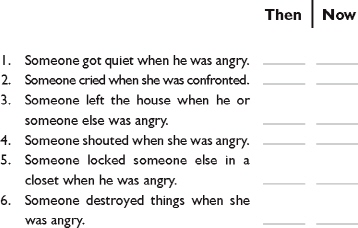

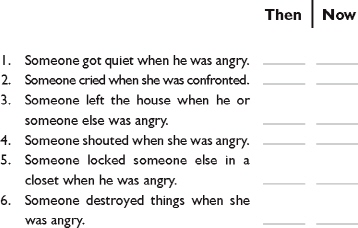

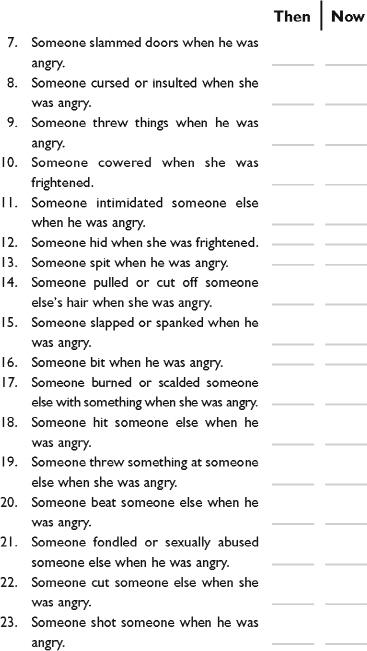

Take a minute to think about how you, as a child, learned to behave from your family. For example, how were disputes settled in your household then? How are they handled in your current relationship? Then do the following exercise. It consists of a list of behaviors that you may have witnessed as a child or things that might have happened to you.

EXERCISE

Behaviors, Then and Now

Place a check mark next to each item that applies to your experiences growing up and a check mark next to each item that applies to how you handle things now. You might end up placing two check marks next to a single item, meaning that your own behavior or the behavior of those around you hasn’t changed since you were a kid.

Becoming aware that exposure to any of these anger strategies as a child may predispose you to their use in your current relationship may help you avoid the situation.

Cognitive Theory

You remember, shoulds! The cognitive theory regarding the development of violent traits in families goes back to the belief that children are molded by a number of things, but perhaps most important by parental messages and expectations. This theory holds that dysfunctional messages or deficits in early education regarding self-efficacy can have consequences later in life as the adult tries to respond to different situations without the appropriate tools.

Look over the following list that contains phrases describing certain characteristics associated with people who are angry or who may experience violence in their relationships. Items on this list can pertain to both males and females. See if any apply to you, because if they do, this book is for you.

An angry person or a person experiencing violence in his or her relationship may:

Have been abused as a child

Have a father who abused the mother

Have parents who were inflexible and controlling

Be jealous and possessive

Be highly controlling in relationships

Have a black-or-white view of life

Have a dual—Dr. Jekyll, Mr. Hyde—personality

Be afraid his or her spouse will leave

Use sex as aggression

Have a low opinion of women

Use denial as a coping mechanism

Use blame as a coping mechanism

Be competitive and use one-upmanship to win

Have difficulty with intimacy

Define or confirm his or her own identity through his or her spouse or partner

Possess a low level of self-responsibility

Be fearful of people

Have a difficult time identifying and differentiating feelings

Have a low tolerance for stress

Place unrealistic demands on him- or herself, spouse, and children

Be highly controlling in relationships

Possess a rigid coping style, not spontaneous

Have poor self-esteem

Have parents (one or both) who are alcoholic or have problems with drugs.

Objects Relations Theory

This is another conceptualization of how violence develops in a relationship. Simply put, it’s based on the premise that two at-risk people find each other. Stated another way, the objects relations theory proposes that two people primed with some of the predisposing issues and the same level of differentiation come together and the violence develops as a result of their synergy with each other.

Learned Helplessness

Learned helplessness is close to self-fulfilling prophecy in some ways. It states that if you tell someone that he is a certain thing, over time that person will become what you tell him he is. For instance, say your child comes home from school with a grade of D on an English test, and you tell him that you’re not surprised, because you never were any good at English either. Suppose you say further you bet he’ll never do any better. After delivering a few more disparaging messages like that, do you imagine he’s going to try harder? I don’t think so. Or say you continually tell your husband he’s worthless, that he’s a jerk and he’ll never change. Chances are you’ll get what you ask for. Learned helplessness relates to anger and violence in much the same way. It suggests that after so much derogatory verbal abuse, the victim develops into the very characterization of the person who is despised. This gives the abusive person the supposed justification to brutalize the downtrodden partner even further. And, this type of character assassination and cruelty is in many ways more hurtful than any physical punishment that a batterer can mete out.

One woman I worked with in a battered women’s shelter made this point beautifully. “Sara,” a woman of around thirty years old, was brought into the shelter by the police after being treated for a broken arm at a local hospital. For the first few days of her stay at the shelter, Sara cried quite a bit and stayed in her room much of the time. In time, Sara began to sit in on the groups and go to counseling sessions. Gradually her sadness and isolation lessened a bit and she was ready to talk about what had happened to her. Here’s her story.

She and her partner “Paul” were together for three years. In the beginning of the relationship she was flattered by all his attention. And, as is the case in many of these types of relationships, he had a great need to know of her every move. She assumed this was because he cared about her so much. She had never had so much attention in her life. Paul told her how pretty she was and complimented her on her lovely singing voice and on her skillful artwork.

Their first year together was bliss and they isolated themselves from the world. After about a year though, things started to change. During this time Sara sold some of her artwork and was beginning to make a life for herself outside of the relationship. Paul began to wonder where she was all the time and accused her of having another man on the side. He told her that her artwork was no good anymore; he said, in fact, that it stunk. He told her she was getting fat and losing her looks. He demanded that she call him hourly when she was out, and he pouted and then shouted and accused her of not loving him anymore.

One day he took away her car keys. They’d combined their bank accounts in the beginning of their relationship and now he took her name off the account. As time went by, he refused to allow her to buy clothes and cosmetics and toiletries and then told her she was filthy and smelled bad. He started calling her hurtful names. She tried to please him in the beginning, starving herself and bathing twice a day, but eventually she gave up. She felt as if she had nowhere to go, no money, and no access to a car. She stopped doing her art and sat at home becoming more and more depressed and disheveled. By the time Paul started to beat her, Sara believed what he told her about herself was true. A neighbor called the police on the night he broke her arm and knocked out her left front tooth. The police arrested Paul and took Sara to the hospital.

When Sara was finished telling her story, she said simply, “The broken bone will heal, but I don’t think my heart ever will.” As if on cue, like a tear, part of her front tooth dropped from her mouth. She nonchalantly picked it up from her lap, removed a tube of crazy glue from her pocket, placed a dab to the broken tooth and repositioned it in her mouth. The group remained quiet for some time. There was little anyone could say, but many of them understood perfectly.

The Disinhibition Theory

This is another theory that attempts to explain problematical relationships, and it has some plusses and minuses. In this theory, drugs and/or alcohol are blamed for anger and violence problems. Clearly there is a relationship to anger and violence in families where the use of drugs or alcohol is a problem. It has not been proven, however, that the use of either one causes anger or violence. They can exacerbate anger or violence problems due to the fact that substance abuse causes a loss of control and the loss of a person’s ability to use good judgment and behave in a way that would be more appropriate in a specific situation. Drug users can have legal and family problems; they can be grooving, spaced, or just plain messed up, but there are still people who are addicts who have no problems with violence at all.

Pathology

Pathology can be to blame. Unfortunately people with personality problems are not very good candidates for change when it comes to anger or violence. Fortunately, though, this segment of the population is actually a rather small one. It is not readily treatable with traditional methods, because their anger and violence take a different shape. These people are more likely to be involved with legal entities because their out-of-control behavior leaks out of the confines or their control in much more serious ways. They may require hospitalization or incarceration.

Lack of Assertion

This is the theory considered by many to be the preeminent one for understanding the roots of anger and also violence. Based within the cognitive theory framework, the lack of assertion theory hypothesizes that anger and consequently violence may be based upon a person’s belief system about what is going on. It suggests that anger may stem from a person’s incorrect understanding of a situation. Due to this distorted thinking pattern and due to a lack of appropriate tools to get his or her needs satisfied, the nonassertive person resorts to more primitive strategies for needs fulfillment. Subsequently, in the process, the person sabotages the chances of getting his or her needs met in a safer, more satisfying fashion.

My doctoral dissertation tested this hypothesis and agreed with other research in this regard. Subjects in my study who were better able to behave assertively and to communicate assertively were less likely to be involved in violent relationships than those who were not. Overcoming Anger will help you learn how to behave and communicate more assertively. But first, let’s take a look at some other dynamics that you should know about that can operate in angry or violent families.

Problems Come and Go in a Cyclic Fashion

Many couples who have no violence in their relationship report a cycle similar to the type sometimes present in violent relationships. But for these couples, an angry outburst of one sort or another takes the place of a violent one. What frequently happens when this behavioral pattern is operating is this: Things are going along quite smoothly when, for some reason, something goes out of whack.

Here’s how this cyclical behavioral pattern operated in one family who came for treatment. These clients wanted to discover what they could have done differently. “Katie” and “Tony” were usually happy with their relationship and had been together for years. Sometimes, though, for reasons they didn’t understand, they would have big nasty arguments.

Normally, marriage was fun for them and they enjoyed being together. Their kids were going to school, and everybody was healthy. Katie, the mom, was working part-time, volunteering, and driving carpool. Tony was doing his bit in his job as a salesman.

One day Katie decided her job really wasn’t paying that much and certainly it wasn’t very fulfilling so she decided to quit. She thought she’d do some research and see if she couldn’t find something that not only paid more, but also offered her some advancement. She was also hoping to find a job that had a little more meaning for her or maybe even something she could do from home.

Leaving her job was a unilateral decision. Katie didn’t bother to talk about it with Tony, which was unusual. This couple had a good relationship and were usually on the same sheet of music when it came to making decisions. Usually they discussed decisions like this. But heck, Katie thought this is no big deal. This job was paying her virtually zero. It was not enough to change their style of living or the quality of their lives. So, she went ahead and made the decision on her own.

Upon hearing about her decision, Tony was stunned. Tony had his own agenda. Things hadn’t been going so well at work, because Tony was a salesman who relied pretty heavily on his commissions, and business had been slow for the last couple of months. He hadn’t mentioned this to Katie. He was trying to be a good guy and not worry her. Never mind that he hadn’t communicated with her, here he was, trying to do the right thing and she hadn’t consulted him first. He felt hurt, but instead of sharing what he was feeling, he “harrumphed” and walked out of the room. Katie felt unsupported.

The next week Tony distanced himself. Since she wasn’t working, Katie had more time for the household, so she cleaned like a maniac and cooked big dinners. But Tony pouted and worked late. He missed the dinners and didn’t notice how great the house looked. In fact he criticized her housekeeping. Katie thought he was being thoughtless and selfish. He continued to come home late.

By the end of the week Katie found a job opportunity she thought would be exciting. She called Tony at work to tell him about it. He was tied up in meetings all day and didn’t return her call. Katie was hurt and angry, so she called a babysitter and went out for a dinner with friends. Meanwhile, Tony had had a good day and decided to surprise Katie by taking her out for dinner. When he pulled up to the house, he saw the babysitter’s car in the driveway. He asked the sitter where Katie had gone, and she told him Katie was having dinner with her girlfriends. Making the assumption that Katie had planned yet another thing behind his back, Tony stewed until Katie returned. As soon as the babysitter left, he blew up. No big surprise there!

The couple came in to the office to discuss what had happened. During the session Katie and Tony were asked to go back and, as couple, try to determine what their unexpressed feelings had actually been each step of the way. When explored in retrospect, the progression of blunders they both had made were easy to identify. Unexpressed feelings of confusion, hurt, sadness, and annoyance all took on different aspects in each of their personal attempts to armor themselves against their more vulnerable feelings.

In a “tit for tat” fashion Katie and Tony had upped the ante. Each had backed the other into having to play for higher stakes. In their particular situation, the couple agreed they could have diffused what became a more and more tense situation that eventually terminated in a blowup. They marveled at how one innocuous event led to another and how each event had taken on a life of its own. This was a strong couple, remember. If Tony had shared his feeling of worry with Katie, or if Katie had checked in with Tony at the beginning, a rotten week might have been avoided.

Finally the couple explored whether any of their behaviors pushed buttons at deeper levels as their week of miscommunication and frustration unraveled itself. Katie remembered that when she was little, her father used to behave in much the same way Tony had over the preceding week. Her father’s usual tactic was to distance himself from the family and stay away from home for extended periods of time. Tony remembered that his mother would shut down and give his dad the silent treatment.

Old messages and poor communication had pushed this otherwise happy couple to behave in a way that they never intended to. One thing escalated into another until a point of crisis and catharsis occurred. Because the relationship was a good one, the crisis point was relatively low. Because the family was open, the incident acted as a catalyst for them to seek help in straightening out what was going on. Unfortunately, in more troubled families, it frequently takes more upheaval and more pain before the couple gets some help.

Over the course of the next couple of sessions, Katie and Tony worked on finding strategies to nip problems in the bud and avoid hurtful and angry blowups. This book will provide you with several of the strategies they learned.

People May Wear a Few Different Hats

Many relationships involve a dynamic where each partner assumes one role for a time and then flips into another and then another. You can envision the different roles as a triangle. On the left side of the triangle you find the role of persecutor. On the right side you find the role of victim. On the bottom part of this triangle you find the role of the rescuer. This pattern of behavior can be found in angry families and in violent ones. Depending on the situation and depending on how well people are getting their needs met, they assume one role or another. The roles flip-flop like this:

1. The persecutor uses angry or threatening behavior to get what he wants.

2. Although there may be a lot of satisfaction over “winning,” there may also be some residual guilt, so the persecutor turns into the rescuer. (Perhaps that’s why after an argument, many people report great love making. Or maybe that’s the reason the victim is typically rewarded with flowers or some other form of indulgence after the outburst.)

3. Then, the former victim, feeling vindicated, and for the present time more powerful, may assume the role of persecutor in order to get even. You can see how this pattern of behavior could self-perpetuate in a dysfunctional relationship.

Here’s how this type of role reversal operated in “Teri” and “Jack’s” relationship.

Jack had come for counseling in order to help him get through his divorce from Teri. He was going through the grieving process and trying to determine how things had wound up as they had.

Teri and Jack had met while on a ski trip three years before. Jack and a couple of his buddies decided to take a lesson, and Teri was their instructor. She was athletic and pretty and Jack was immediately infatuated. They went out several times that week and then Jack went back home. They corresponded and Teri came to visit. Everything was very romantic. Teri went back and forth from California to Colorado, and their fairy-tale courtship continued to intensify. Sometimes, though, Jack would call and she wouldn’t call back for days or weeks at time. Other times Teri would call in tears and accuse him of not loving her. He really didn’t know what to make of her unusual behavior, but he was in love and didn’t worry about it too much.

After a few months, with very little time together under their belts, they decided to get married. Teri quit her job and moved to California. A couple of months into the marriage, odd things started happening. Since Jack was a police officer, his duty schedule changed with some frequency. One time he came home to find the apartment torn apart. He explored the apartment’s four rooms and discovered Teri sitting on a disheveled bed with a bunch of torn-up photographs scattered around her. Jack was at first concerned, thinking some intruder had caused the confusion. No, explained Teri, that wasn’t what happened. She was mad because she found some pictures of Jack and another girl, so she wrecked the apartment. Jack was, understandably, very annoyed and yelled at Teri that she was acting crazy. He used a few other expletives to drive his thoughts home.

Teri broke down. She threw herself on the bed and cried her heart out. She told Jack she didn’t know what had gotten into her and that she was very, very sorry. She appeared to be so contrite that Jack felt like a louse, making her cry so much. He kissed her and he cuddled her and he gently put her to bed and then cleaned up the mess in the rest of the apartment.

On another occasion, Jack pulled night duty for several evenings in a row. Teri didn’t like being left alone so she decided to try to get Jack home. She called the officer on duty and told him that she just found out that Jack was having an affair and that she needed him to come home in order to discuss the situation. The officer asked Jack what was going on. Jack told his superior officer he was clueless and didn’t know what Teri was talking about. Nonetheless, Jack was told to go home.

Embarrassed and mortified, he once again blew up at Teri. On this occasion, Teri didn’t back down; she came right back at him using “the best defense is a good offense” strategy. Then Teri abruptly stopped screaming, approached Jack, and gave him a hug and a kiss. She told him everything 82 was okay and that she wasn’t mad at him for yelling at her. They had a great time in bed and Jack felt mollified, if a bit confused.

The marriage finally came to an end when Jack returned home from work one afternoon to find Teri and another man in bed together. Jack had once again been cast as the victim. At this point in the situation, Teri was entrenched in her role as the persecutor. Jack went ballistic when he saw them together and ordered the guy to get out of the house. He continued to argue with Teri, cursing at her and at the same time telling her how much she had hurt him. In other words, Jack assumed the role of the persecutor.

When Jack took on his new role, Teri flipped out of her role as she fell to the floor crying. Just like clockwork and true to form, she assumed the role of the victim. Jack was now feeling he was in the power position and subsequently he felt like he could be magnanimous. He decided he could afford to be gracious and rescue poor Teri, so he went over to her and embraced her, at which point she bit him on the pectoral muscle, hard. That was the final straw. Jack woke up and walked out.

Now he sat in my office trying to understand the dynamics that had sucked him into an unhealthy relationship in which he continually felt bad about himself. He had fallen victim to powerful gamesmanship. But, fortunately for Jack, he left the game before it was too late.

Take Me to Your Leader

Another pattern that may develop in families subjected to the tyranny of violence or anger and the threat of violence is one that resembles the phenomenon known as the Stockholm syndrome. The Stockholm syndrome is the name given to a constellation of behaviors that frequently develop among people who are held hostage. It can develop as the result of the use of tactics not unlike those used on prisoners of war. The Stockholm syndrome also provides us with an explanation of why abused children will defend their abusive parent and beg to stay with them even when they are at risk of further abuse or injury.

These behaviors develop due to techniques used by the captor or, in family relationships, by the person with the power and control. The bottom line is, people tend to want to join with the people who have the power. You could say that these techniques are the extreme form of Machiavellian disinterest and are extremely powerful tools for gaining compliance. It will be helpful for you to become aware of the techniques used by controlling individuals and discover if any of them are operating in your relationships.

Degradation

This type of treatment can take the form of low-level verbal assaults and put-downs that are damaging to a person’s self-esteem. At the upper end of the spectrum, degradation may involve actually confining someone to a locked room and forcing that person to remain filthy or nude. This type of treatment reduces the victim to very basic concerns like being allowed to go to the bathroom or take a bath or get a blanket.

Enforcement of Trivial Demands

In this situation, the person in control sees to it that demeaning and meaningless demands are met. This type of demand might be something as unnecessary as asking somebody to rearrange the dishwasher in a certain way or refold all the towels differently. Due to the random nature of these demands, the underdog becomes confused, wary, and vigilant, wondering what will come next. Every move the underdog makes becomes potentially dangerous for him. This tactic develops the habit of compliance.

Granting Occasional Indulgences

This type of intermittent positive reinforcement provides motivation for continued compliance. This on-again-off-again reinforcement agenda is the most powerful, because it allows for the captive to remain hopeful of a positive outcome as long as he or she cooperates.

Inducing Debility and Exhaustion

Treatment like this might manifest itself as continually waking one’s partner from sleep or interrupting the partner when he or she is in the middle of some task. It’s crazy making and it weakens a person’s mental and physical ability to resist.

Demonstrations of Omnipotence

These maneuvers serve quite simply to suggest the futility of resistance. The person with the power finds a means that shows the weaker one that she’ll never win.

You can bet in the movie The Godfather, when Johnny Fontaine awoke to find his horse’s head at the foot of his bed, he got the message loud and clear that Don Corleone was pretty darned omnipotent and he’d better pay attention to him.

Threatening Behavior

At its most basic, threatening behavior cultivates an atmosphere of anxiety and despair. There’s an old story that may explain what this type of behavior might look like. It goes something like this:

In the old West there once lived a rancher who decided it was high time to find himself a wife. Since there was no likely candidate in the surrounding area, the rancher, a no-nonsense kind of fella, decided a mail-order bride would do just fine. The rancher was not one to waste time so he went down to the Western Union office in town where he sent a telegram to a mail-order outfit he’d heard about in Kansas City. The telegram enumerated his needs and the necessary qualifications for his bride-to-be.

In due course, a likely lady was found. A contract was drawn up and all the arrangements were made all proper. A fortnight later, when the rancher’s lady arrived at the train station, the rancher greeted her pleasantly. Being a no-nonsense kind of fella and not one to waste time, the rancher then escorted this lady over to the town’s courthouse, where a justice of the peace hitched the two of them. It was a fine little ceremony.

One of the town ladies, Mrs. Maudy, saw the two of them exit the courthouse and sashayed over to see what was up. She sidled up to the new bride and inquired just as nice as you please, who might this lady be and what might she be doing in town. The rancher turned toward Mrs. Maudy and in a not-so-nice fashion told her, “Mrs. Maudy, that is none of your business!” His new bride was somewhat shocked, but she said nothing.

They started back toward the buckboard that was to convey them to the ranch. The rancher confided to his wife, “That durned Mrs. Maudy, she’s a terrible gossip. I don’t need the whole town knowin’ my business.” He shook his head in disgust and smiled at his bride. “I never could abide it.” The rancher helped his bride and her luggage on to the cart and told the chestnut mare “gaddap.” The horse was slow to respond so the rancher cracked his whip in the air over the animal’s head and yelled at the nag, “Gaddap you lazy thing!” The horse complied. “Laziness,” the rancher said and shook his head in disgust. He smiled at his wife. “I never could abide it.”

About a half mile from town the newlyweds came upon a gang of boys shooting marbles in the road. The rancher told the kids to get out of the way and cracked his whip in the air. One of the kids told the rancher to go around them as there was plenty of room. The rancher took out his Colt and shot it in the air. “Get out of my way you durned rascals!” They got out of the way. His new bride was somewhat shocked, but she said nothing. The rancher replaced his gun in its holster. “Smart-aleck kids,” he said. He shook his head in disgust and smiled at his bride. “I never could abide ’em.”

The rancher and his wife went on. The ranch house was finally in sight. As they approached, an old donkey ambled onto the road, blocking the way. “Get out of my way,” the rancher called. He got no response from the spavined thing. Next he took out his whip and cracked it over the beast’s head—still nothing. Finally, the rancher took out his Colt and shot it in the air. The donkey swished his tail. The rancher pointed his gun and shot the unfortunate donkey dead. His new bride was somewhat shocked, but she said nothing. Once again the rancher holstered his weapon. “Stubbornness,” he said. He shook his head in disgust and smiled at his wife. “I never could abide it.”

He helped her down from the cart and headed toward the tidy ranch house. As they got close, the bride noticed a headstone off to the right. She approached it and her husband followed her. “That’s the grave of my first wife, Martha,” the rancher said. “Oh that woman had a mind of her own, she did.” He shook his head in disgust and smiled at his wife. “I never could abide it.” He walked toward the ranch house stoop. His new bride turned and took a look back at the road. She followed her husband into her new home.

Monopolizing One’s Perception

This technique eliminates any type of stimuli that may compete with the personal agenda of the person in power. It fixes the weaker person’s attention on his or her immediate predicament and it fosters introspection into the situation. The person becomes more and more distanced from the world and its reality checks and instead becomes fixated on the present. This technique frustrates all actions that are not consistent with the power person’s rules for compliance. The person whose perception is monopolized becomes more and more concerned with the details of following the rules to the letter, to the exclusion of caring for him- or herself or caring about the situation.

Isolation

In this situation victims are deprived of all social support systems that might supply them with an ability to resist the whims of the one in control. The people trapped develop an intense concern for themselves and their relationship with their controllers. In hostage situations, isolation helps in making captives dependent upon their captors for news of the outside world and all of their basic needs. Isolation can be translated into a relationship when one partner forbids the other to associate with friends or with family, and the stronger partner controls all incoming information.

Five Power Trips

There’s nothing wrong with having power or with using power if it’s done legitimately. There are a few types of power you may want to review in order to decide if you are using power or abusing it. Each type has its uses, some good, some not so good.

1. Legitimate power. This is the kind of power that is derived from position and includes power coming from elected or selected positions. An example of legitimate power would include things like presidential power, the power a minister has to marry someone, or a captain’s power to command his sailors and run his ship.

2. Referent power. This type of power refers to that which is derived from one’s personal characteristics. Examples of this kind of power could include traits like affability, amiability, likeability, and personal charisma.

3. Expert power. In this category, power comes from somebody’s greater expertise or knowledge in a specific area. Examples of this type of power include that of a teacher in the classroom or a doctor doing surgery. You wouldn’t want the woman from the dry cleaner’s working on your appendix.

4. Reward power. This power is derived from the ability to give benefits to another person, ranging from monetary to psychological benefits. Used benignly there is no problem with it. Examples of appropriate use of this type of power include congratulating someone on a job well done or giving a good worker a raise. Problems arise when reward is used in a way that keeps someone in line as a means of controlling that person.

5. Coercive power. This type of power is derived from the ability to punish. Examples of this type of power include the power a judge uses to sentence a felon or the power a priest uses to excommunicate someone. Although reward power is a potentially tricky one, coercive power is really the one with the most problems on a personal level. Coercive power is the power used to control another in a relationship This punitive means of control is the one you need to watch out for and determine if it’s operating your relationship.

Are You in Control or Out of Control?

If you’re concerned because you identified with the kinds of controlling techniques you’ve read about in this chapter, you may want to look for any areas of your life where you feel you are either trying to control or being controlled. Areas of control to watch out for are:

• Financial. Do you try to control your partner’s finances? Is your partner trying to control yours? Obviously, when there’s been an agreement about money matters, there’s no need for concern. If your husband is a spendthrift and the two of you decided he operates better when he’s on an allowance, that’s fine. There would be a concern, though, if a husband or wife took total control for no good reason or where money was doled out, or not doled out, as a reward or a punishment for specific behavior. Has you spouse ever tried to keep you from getting a job when you wanted some of your own personal income? Have you ever tried that with your partner? Other ways this power might be demonstrated are when one partner forces another to beg for money or takes away a checkbook or credit card.

• Emotional. Do you try to control your spouse by granting, or not granting, sexual or emotional favors? Do you play mind games with your spouse or worry about your spouse’s mood? When you’re mad, do you ever try to make your spouse feel guilty? Do you humiliate your partner? Do you resort to using put-downs when you’re angry? Does your partner make you feel guilty or humiliate you? Do you or your mate use the silent treatment to get what you want? Do you ever try to make your partner feel as if he or she is crazy?

• Use the children. Do you or your partner use the children in order to relay messages to each other? Do either you or your spouse or ex-spouse use the kids to make each other feel guilty? Do either one of you threaten to take the children away when you’re angry? If you’re separated, do either of you use visitation issues to harass each other?

• Minimization and denial. Do you or your partner make light of serious issues or behave in a conde-scending way toward each other? Do you shift responsibility, and blame your partner for mistakes you made? Do you tell your partner that it is his or her fault that you had a fight? When angry, does your partner try this maneuver on you?

• Coercion or threatening behavior. Have you ever made a threat, or carried one out, against your mate? Has your spouse ever threatened to leave you or commit suicide in order to get his or her way about some issue? Has your mate ever tried to get you to do something illegal or report you for something? Have you ever done something like this to your mate?

• Intimidation. Do you or your spouse try to make one or the other afraid with your looks, gestures, or the things that you do? Does your spouse smash or destroy your property? Do you ever break your mate’s belongings? Has a family pet ever been abused?

If you find that you recognize any of these dynamics, you’re not alone. They happen to a greater or lesser degree in many, many families. There are, however, much better ways of getting your needs met and having a happy, successful relationship. The following chapters provide you some new ideas and strategies for improving the way you feel about your relationships.