It’s now known that stress bears a relationship to not only our emotional state, but also to our physical health as well. Research established this connection by focusing on the measurement of endocrine responses in bodies under stress. One model for what happens to the body when stressed is the general adaptation syndrome.

The hallmark of this theory is its three-stage model of stress that includes the alarm stage, the stress resistance stage, and the exhaustion stage. In the alarm stage, the “flight or fight” response, which was discussed in the Chapter 1, again puts in an appearance. Just as it does when you get angry, this automatic arousal mechanism prepares your body for whatever may come next. As we know, this response is highly adaptive and crucial for our survival. Thanks to your body’s sympathetic nervous system, when what is perceived as a threatening stressor occurs, your body automatically prepares to face it.

The stress resistance stage occurs after the immediate threat disappears. Your body relaxes slightly, but it still continues to stay mobilized for action as stress hormones, like adrenalin and cortisol, continue to be released into your body. Vigilance remains increased, and your body is still scanning in a “just in case” fashion.

Finally, if the stress level stays high, your body enters the exhaustion stage. After long or repeated exposure to stress, your body’s adaptive energy capacity becomes exhausted. It just gets zapped. It is at this point that you can experience lowered immunity or a tendency toward accidents, bad judgment, and anger blowups.

Here’s a practical example of how the general adaptation syndrome works. Say you just avoided a near collision (the alarm stage). You had to swerve like crazy and do some fancy brakework, but it looks like the guy who nearly creamed you is well out of the way. You may notice that your heart is pounding in your ears. Also, you are aware that your right leg and right foot are still shaking. You sigh, your eyes keep finding the rearview mirror, and you glance left and right.

You are now at the resistance stage of stress. If you were to remain in this state, you could enter the exhaustion stage and you might end up with a terrible headache, leg cramps, and who knows what else. It’s possible that you’d feel so goofed up and so cranky that you’d do something really stupid.

Right Brain/Left Brain—It’s Not a Tossup

It is thought by some researchers that early man probably didn’t differentiate between himself and the “other” very well. He had no conscious awareness of “I” versus “it.” Everything was part of nature; everything was part of everything else. Man was just one aspect of a world and a sky that were full of magic and mystery. However, nowadays we do differentiate between “me” and “you” and “it.” We are also aware that the brain’s two hemispheres are responsible for different functions and that in order to function properly as whole beings, we need to use both.

Some research suggests that around 3,000 years ago, or maybe back even a bit further in time, man became selfaware. He became aware of himself as an entity apart from other things. He began to develop consciousness. This self-awareness helped him begin to see that his “essence” was not the same as his nose or foot. The French philosopher Rene Descartes described this distinction when he made his famous statement, “I think, therefore I am.”

Much of the time we operate in what’s known as a right-brain mode. The right brain provides us with a holistic, integrated, relaxed look at the world. Unlike the right brain, the left brain is more concerned with focusing on the here and now: It works in a more linear way, more like a computer. When you learn a task, your left brain is quite active and aware. For example, if you ever took tennis lessons, you may remember what it was like.

You had to be aware of where all your body parts were at once. Not only did you have to keep your eye on the ball, you had to be concerned with how far away you were from it and whether you were perpendicular to it. You had to think about where your feet were and if your backhand had follow-through. Then, hopefully, as you learned more, you allowed your right brain to get in there, too, and you relaxed—and your game improved.

Learning to drive presents another example. When you were first learning this skill, you were aware of everything. You kept your eye on the old guy with the white hair and the floppy green hat getting ready to cross the street. You noticed he had a cane. In a nanosecond you speculated on whether or not he would trip in front of your car when you passed through the intersection. You checked the speed you were traveling. You were aware that “Hey Jude” was playing on the radio. You gauged the yellow light at the corner, analyzing things, to see if you could make it. You saw the cop sitting at the corner to the left. You figured you’d better not chance making it through the yellow and got ready to stop for the red.

When you first learned to drive, these threads of information were things you were consciously aware of seeing or hearing on an individual basis. You were using your left brain. As your skills developed, you made the shift to a more relaxed driving style and the individual pieces wove themselves together, becoming part of an integrated “fabric” of the driving task. Driving now, operating primarily with your right brain, you still are conscious of everything and all the facts are still available if they’re needed, but you are aware on a different level. This frees you to an extent to ruminate on what you’re going to have for dinner or on whether or not to see a movie on Friday night. When threat arises, however, you revert to the other type of processing, utilizing more of your left-brain capacities, focusing on relevant and crucial facts for dealing with critical situations. It becomes a “me against them” situation. It’s the survival instinct. It’s appropriate and necessary, but it’s tiring. In fact, if you stay that way, you wind up pooped.

The Relation of Stress Resistance to Anger

The stress resistance stage also works on an interpersonal level. Suppose you are having problems at home. Here you are, in front of your house after a bad day at work or school. As you ready yourself to open your front door— because of what’s been going on—your left-brain scanner activates. You’re ready for trouble. Perhaps you’re even rehearsing different defensive strategies in response to any of several different conflict scenarios that you anticipate could unfold.

Because you’re late, you figure your husband is going to grill you about where you’ve been. You expect he’ll probably complain that dinner isn’t ready, too, or that you didn’t get all the clothes folded and put away. So, before he gets on you, you decide you’ll remind him up front that he keeps forgetting to fix the broken sprinkler and never remembers to take out the trash.

You enter the house and find him in the kitchen preparing dinner. Aroused and ready to interpret nuances of even the most innocuous events in a negative or threatening way, you may actually be responsible for what’s known as a “self-fulfilling prophecy.” You’ve front-loaded yourself. Armed for bear, you don’t read the situation correctly, and you overreact. Oh great, you think, your husband never cooks. You just know he’s mad. Figuring that the best defense is a good offense, you start to tell him all his faults. He feels like he’s being attacked. All he was trying to do was surprise you with a couple of steaks. His feelings are hurt, but instead of saying so, he blows up, throws the frying pan, and stomps off to the garage.

Basically, you mishandled the situation due to your frame of mind and incorrect interpretations. Or you wind up blowing it because of the way you adapted your behavior to meet what you perceived to be a negatively loaded situation. So, you not only added to your stress level, but also may have actually caused the situation you wanted to avoid, a confrontation. And you may not even be aware of your part in it!

Your Body and Mind Under Siege

Unfortunately, the more these types of stressors occur, the more likely you are to put yourself at risk not only for anger, but also for illness and accidents. Your body reacts to stress both physiologically and psychologically. Maybe you’ve experienced this phenomenon when, for instance, after a prolonged period of stress, things finally seem to lighten up and then you come down with a cold. A stressed-out body is likely to suffer lowered immunity to disease and be more prone to anger.

In your body’s attempts to prepare for stressful situations, it reverts to the same coping mechanisms our ancestors called into action for a quick dash across the plains. You experience automatic physiologic responses that are great for short-term threats, but leave you trashed over the long haul.

How Long-Term Physiologic Stress Affects Your Body

Muscle tension is fabulous when quick reaction times are important, but over time, strain can lead to cramps and muscle-induced tension headaches. Breathing increases that serve to supply more oxygen for rapid bursts of energy and quick thinking can lead to problems with hyperventilation and, ultimately, blackouts. Under stress, digestion is interrupted or stops altogether. Your bowel can be affected, too. Need I say how? The problem is, if you’re under a great deal of unremitting stress, you’re continually invoking your body’s stress response, which can lead to digestive problems like ulcers, indigestion, spastic colon, and colitis.

Hearts work overtime under stress. The relationship between chronic anger and heart attack is now virtually accepted. Noted physicians like Andrew Weil and Dean Ornish teach stress-management techniques to their patients to help them avoid further problems. Hypertension is also a real problem for many people in the United States. Stress increases red corpuscles, which can result in clots in the bloodstream. Management of high blood pressure can include medication, attention to diet, life-style changes, and reducing stress.

Psychological Effects of Stress

When you’re stressed, you may begin to notice certain psychological symptoms such as these:

• Minor problems throw you off or seem insurmountable; you may notice that even little things really bother you, or that little things seem overwhelming.

• Tasks that once were easy may become onerous and you might have trouble concentrating.

• Being around people may feel threatening because you may feel distrustful of others. Former friends may not be coming around much and seem evasive.

• You may believe there’s no one you can talk to or that you’re trapped in your predicament with no way out.

• You may find that you’re always thinking about your problems, ruminating on them to the exclusion of other things. This preoccupation can ultimately lead to accidents and bad decisions. If you’re not taking care of business in the here and now, you become accident prone.

• Formerly fun activities, like sex and eating, may no longer bring you any pleasure or become distasteful. This inability to feel pleasure is called anhedonia, and it’s not good.

• You may be having a hard time getting along with other people or feel fatigued and exhausted. You may be getting into fights.

• At work or school or in social interactions, you may have noticed that your productivity is down. Others might have commented on it.

• You may notice that you’re not sleeping as well as you once did or that you’re sleeping all the time.

• Maybe you caught yourself eating too much or too little or drinking or smoking when you never did before.

If any of these symptoms sound familiar, don’t be surprised; you’re reacting to stress. We all do, in different ways and to different degrees. When stress manifests as anger or when physical or psychological symptoms become chronic and zap your quality of life or become threatening, it’s time to take another look at what’s going on and seek some outside help. Your stress may have pushed you to the edge of an anxiety disorder or clinical depression.

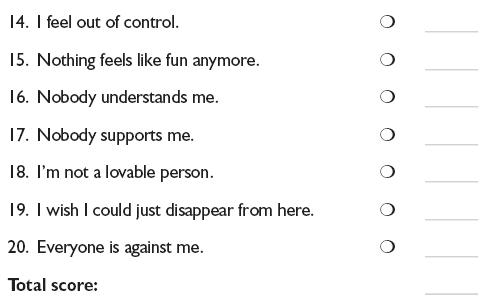

Generally speaking, becoming aware of your problematic situations, being willing to look at yourself nondefensively, and being open to change can work little miracles. To see how you’re coping with stress in your life, try the following exercise. It’s a list of negative thoughts that pop into everybody’s head, and in this exercise you rate how frequently they pop into yours. Your score will tell you how well you cope with stress.

EXERCISE

How I Cope with Stress

Check any thought you had over the last week, then indicate how frequently it occurred, assigning a value of 1 through 5 for each one. Remember, everyone has negative self-thoughts sometimes!

Not at All = 0

Almost Never = 1

Moderately Often = 2

Often = 3

Constantly = 4

If you scored 30 or under, you’re handling stress pretty well. If you scored above 30, take a look at the areas that are causing you the most discomfort. It’s those negative thoughts you’ll want to focus on first.

Time Is of the Essence

Over the years there’s been a debate about how two different personality types, dubbed “A” and “B,” fared when it came to anger and stress. Originally identified by two cardiologists, the people with these personalities were supposed to have quite different ways of dealing with anger, stress, and life in general.

Type A Personality

Type A people are described as overly competitive, impatient, and easily frustrated. They are said to be hard on themselves and overly critical of others. In conversation, A’s tend to talk quickly and hurry conversations. If they think you’re speaking too slowly, they may finish sentences for you. A’s supposedly also move quickly, try to do more than one thing at a time, and love to be involved in multiple jobs with multiple deadlines. A’s are always conscious of the time—in fact, they’re overly conscious of it. A’s never are late, and, indeed, they are likely to be early. They are always trying to better themselves. Not surprisingly they are, for the most part, the world’s overachievers.

Originally it was believed that A’s made up the majority of the world’s heart-attack patients. Later research on the subject suggests it’s not so much the Type A style itself that leads to a heart attack, but that Type A people who are chronically angry are at risk.

Type B Personality

Type B personalities, on the other hand, are, well, let’s just say they’re the opposite of the A’s. They’re described as laid back and much more stress tolerant. B’s don’t worry if they’re late—so what, it’s no big deal. If the baby has a little poopy in his diapers, the B will get around to changing him, eventually. As you might well guess (especially if you see in yourself some A tendencies), B’s could make the A’s crazy.

Managing Anger: Type A vs. Type B

The A/B personality hypothesis is worth considering when it comes to anger and self-management. Remember that anger managers use problem situations as opportunities for constructive change. People can certainly be a mixture of both Type A and Type B in different situations, but those with more high-strung personality styles are more easily aroused. So, if you find that you have more A than B in you, it behooves you to examine your behavior to determine if you are placing yourself at risk for self-angering situations. If this is the case, you can take control and provide yourself with escape hatches to avoid these situations.

If you find that you are an A, take some time to discover what areas are problems for you, and think about ways you can get what you need without becoming annoyed or angry and without turning off those around you. For instance, if you’re an A, take that into consideration in transactions with other people. Do you arrive at places early and then feel totally frustrated and angry that no one else is there yet and you’re wasting your time? Since it’s probably impossible for you to make yourself be late or even on time, bring a book with you, take a project to work on, file your nails, or organize your Palm Pilot. You have to play the cards you’re dealt, after all.

If you’re an A, some of the situations like the examples that follow might cause you problems. Feeling as though it’s the principle of the thing, you may try to tough it out. Or you may feel almost compelled to do things the way you always do them, when with a little creative problem solving, you could either avoid what bugs you or at least defuse the impact upon you. To help you think about how you can avoid or defuse the impact of circumstances that normally aggravate you, read the following problems and consider the obvious solutions recommended for keeping you on an even keel:

• Problem 1: It’s Saturday afternoon and you’re at the mall. You know there is never anyplace to park and you know wasting your time driving around in circles makes you angry. Obvious solutions:

a. Try going early (or late) on a Monday.

b. Shop online.

c. Use the phone.

• Problem 2: You’re headed out to get the newspaper and that annoying neighbor who talks on and on and complains about everything is down at the curb. Obvious solutions:

a. Wait to get the paper.

b. Have your spouse go for you.

c. Train the dog to do it.

• Problem 3: You’re forced to sit in unending traffic on the highway. It’s brutal; it drives you crazy. Obvious solutions:

a. Take another route, even if it takes a bit longer.

b. Try going at a different time.

c. Try using books on tape to keep your mind off the waiting.

• Problem 4: You’ve decided to go back to school, you put off writing your final paper until the night before it’s due, and now your child has started throwing up. Obvious solutions:

a. Arrange for backup help in advance.

b. Learn new ways to prioritize.

c. Complete assignments as soon as they are assigned.

Time Management Techniques to the Rescue

Whether you’re a Type A or Type B, a few time management ideas will help you feel less stressed out and less angry and pressured. An easy way to visualize a time management model is by picturing a series of drawers. In the top drawer go things that need immediate attention. The second drawer contains things that will need to be dealt with very soon. The third drawer holds items that will have to be dealt with eventually. The bottom drawer is for things you’ll probably never get around to. You may already be familiar with the time management chest of drawers model. It’s a classic.

Time Management Model

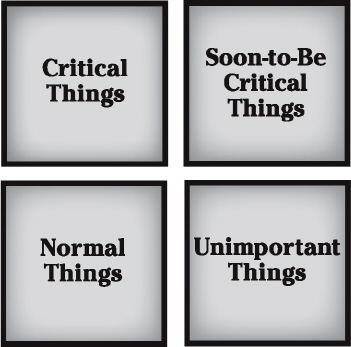

The Four Boxes of Time

Somewhat like the time management chest is another useful time management tool. I call the model the Four Boxes of Time. It looks like this.

Four Boxes of Time

By using this model, you can divide your waking hours more appropriately, which will enable you to prioritize things in order of their importance.

Box One: Critical Things

In this box are things that are crucial to your life— things that could lead to disaster if put off, such as necessary surgery, funerals, important money matters, and so on. Many people operate out of this box helter-skelter, which leads to constantly putting out fires. They never seem to have a chance to take things as they come. For them life is an angering, continually looming disaster. If you believe you are operating primarily out of the first compartment, you should probably take a step back and reevaluate your priorities. To maximize your time management, do your best to keep the first box as clear as possible, but remember, life does happen and you’ll wind up with stuff in there whether you want it or not.

Box Two: Soon-to-Be Critical Things

In the second box are things that are important, but not yet critical. These might be things like next month’s house payment bill or remembering that the kids need their shots or that you need to renew your driver’s license next month. Be careful! If not managed, items in box two can become critical!

Box Three: Normal Things

The third box contains things that should get done eventually or they’ll probably wind up in the second box. This box could hold magazine subscriptions you might like to renew, appointments you’ll want to make eventually, things that aren’t imminently important. You’re ultimate goal is to keep yourself operating in boxes two and three. In these areas you are able to take care of things as they come along, not allowing unfinished business to become catastrophic.

Box Four: Unimportant Things

In the final box are things that really can be put off, such as organizing coupons, cleaning out the garage, learning how to burn CDs, writing to Aunt Ethel, and stuff like that. Attend to issues in box four when you have time or are really, really bored.

Finding Balance

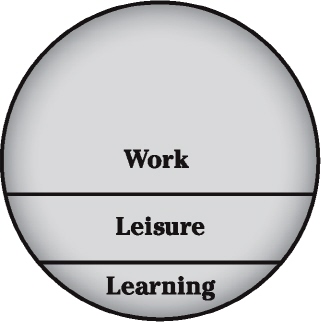

In order to live in a healthy way and keep ourselves from becoming stressed out and overwhelmed, we need to provide ourselves with the time to nurture three aspects of life. To achieve balance, we need to make time for work, for leisure, and for learning. The time spent in each of these areas ebbs and flows over the course of our lifetime.

As little kids, we overlap the three aspects quite a bit, and they are rather blurred. Leisure, or play, is the main component, but within the area of play, a bunch of learning takes place and so does a lot of work. As children grow a little older, the areas become more clearly defined. Learning takes the shape of schooling and work may take the form of chores.

Balance Wheel, Childhood

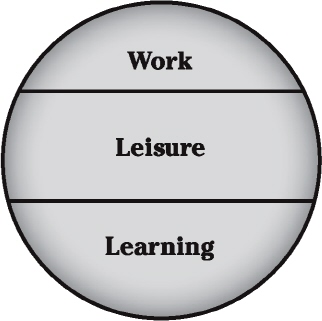

The focus changes somewhat as we become adults and the work area of life gains true ascendance. For many people at this stage of life, the learning area becomes secondary or nonexistent, and the leisure area may be sacrificed to enhance the more critical work area. Work, it’s true, is a very necessary part of adulthood. But many people sacrifice balance in its service, and to do so can produce stress. All work and no play makes Jack a dull—and possibly angry—boy.

Balance Wheel, Adulthood

As middle age approaches, many people, if they are fortunate and if they work at it, experience a renaissance in the leisure and learning areas of their lives. As their commitment to traditional forms of work diminishes, they have the time to rebalance their priorities.

Balance Wheel, Middle Age

If you have been feeling stressed out, overwhelmed, or angry, you may want to see how well you’re balancing your time. Your priorities may need a bit of a tune-up.