The next morning I learned that another pilot was scheduled to fly with Colonel Passarello. I was going along to observe. I was told that was the way it had been scheduled, but I couldn’t help feeling my displacement was because of my poor performance the preceding day. I strapped myself onto the bench seat at the rear of the cockpit, resigned to watching others fly the airplane.

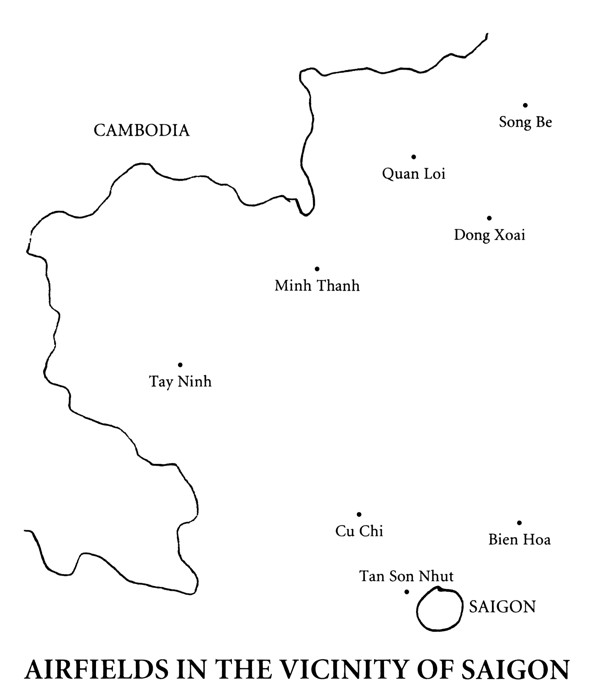

We flew first to Tan Son Nhut, where we learned we were to carry troops and equipment between Quan Loi and Minh Thanh, two small fields west of Saigon, near the Cambodian border. Minh Thanh was literally a wide spot in the road. Located in the middle of a rubber plantation, the field had been made by widening a small dirt road that ran straight through a forest of rubber trees. The dirt surface had been treated with oil to reduce the dust and to keep the surface from washing away in the rain. The field was long enough. The problem was the approaches to the field: tall rubber trees lined not only the sides of the dirt strip, but also the approach edges at both ends. In landing, Passarello had to carry just enough power to hold us above the trees, then when the tree line passed, cut the power, and just before slamming into the ground, add power to check the descent, then retard power to land. This he did with practiced skill, bringing us in to a smooth landing.

Quan Loi was a fifteen-minute flight north. One end of the runway was cut through a stand of trees, but the other end of the runway ended in the back yard of a rubber plantation. The plantation, which was owned by a French family, was used as a headquarters for Army operations in the area. It was a picture-book setup, with a large, elegant-looking main house and several other buildings nearby, white and glistening in the sun.

Army Huey helicopters moved in and out of the central area at the end of the runway, refueling with their engines running, their blades stirring up clouds of fine, red dust. The skin of the ground troops was painted a dull red, the color of the dirt in the area. One Huey refueled while other helicopters hovered in the fringe area, waiting their turn to come in and refuel. Each Huey crew chief ran over to the central area, picked up a refueling hose, and brought it over to the helicopter. The refueling hoses were connected by a pump system to a series of large, heavy rubber bladders filled with JP-4. The fuel bladders were brought in by C-123 and C-130 aircraft. I asked the ground crewman if all this activity was usual. He shook his head. “Nope. Big operation going on a few miles to the west, near the Cambodian border.” I could believe it, for as fast as one helicopter refueled, it rapidly departed low and to the west, and another took its place.

I sat on the rear seat again as we took off for the short ride to Bien Hoa, carrying a few troops back to their home area. Unlike Tan Son Nhut, which was Saigon’s main airport and served civilian as well as military aircraft, Bien Hoa was exclusively a military base, home for many American and South Vietnamese Air Force flying units. To the south, a wide river snaked its way across the horizon—the Saigon River, the natural line that separated Tan Son Nhut air traffic from that of Bien Hoa. The land around was completely flat. We landed to the west, the bright red ball of the late afternoon sun obscuring our vision. After a quick offload, we headed back to Nha Trang, landing just as the sun set behind the hills to the southwest. When we walked into the Nha Trang ALCE, I noticed one of the men behind the desk pulling out a series of paper cups and pouring something into them from a large bottle.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“That’s your combat ration—a shot of whisky. A tradition that goes back to World War II. After every combat mission, you get a shot of whisky. Here you are.” And he handed me a small paper cup filled with strong-smelling brown liquid.

Quan Loi, March 1967. French plantation buildings in foreground.

I took a small sip. When I swallowed, it felt like it was stripping the skin off my throat.

“Agh!” I said. “It’s terrible!”

“You think so now,” someone said, “but after a few weeks on the shuttle you’ll change your mind.” It didn’t seem likely.

The following day I was once again the only pilot flying with Colonel Passarello. When I walked through the crew entrance door, I saw that the cargo compartment was filled with what looked like large, inflated balloon tires lying on their sides tied down on the aluminum cargo pallets. I placed my hand on the closest sample. It gave when I pushed on it.

Brownie saw me examining the cargo. “Seen those before? They’re fuel bladders full of fuel. Remember those Army helicopters refueling at Quan Loi? Well, that’s what these are.”

“For Quan Loi?” I asked.

“Nope. Ban Me Thuot.”

Ban Me Thuot was a decent-sized, east-west landing strip in the middle of a large, flat plain about 75 miles west of Nha Trang. The town of Ban Me Thuot, located five miles to the southwest, sat on the main north-south road between Pleiku and Saigon.

At Ban Me Thuot a fork lift carefully removed the bladder-laden pallets. The thought of twenty of these bladders full of fuel in the cargo compartment made me nervous. I had visions of fuel leaking out into the floor of the cargo compartment. All it would take was one spark, a short in an electrical system, or ground fire hitting us in the right spot, and we would have an explosion.

Our next hop was a flight straight south to Phan Thiet, another new field. The terrain between Ban Me Thuot and Phan Thiet was rugged and mountainous. Phan Thiet was located on a slight rise overlooking the South China Sea, halfway between Cam Ranh and Vung Tau. This was another new, challenging field for me, and Passarello flew the aircraft from the left seat. The field was located on the edge of the land-sea border, another short brown line running more or less parallel to the shoreline—the same kind of runway as at An Khe Golf Course, aluminum matting, and about the same length. Unlike the Golf Course, however, this runway didn’t disappear as you descended. In fact, it was slightly bowed in the middle, like a shallow dish.

The far end of the field, the end nearest the sea, widened into a parking area where many aircraft were parked randomly. Unlike the field at Quon Loi, where the parking area at the end was large, this parking area was small. Passarello observed that landing from the sea to the southwest, you often flew over parked aircraft before touching down. You had to be careful not to let too much runway pass beneath you before touching down. But most of the time, because of the onshore breezes caused by the close proximity of the sea, we landed as we were now, to the northeast, towards the parking area.

From Phan Thiet we picked up a load for Tuy Hoa, where we landed on the aluminum matting runway. The field was dry and dusty, as the construction equipment was working at an intense pace to complete the concrete runway. I made the landing there with reasonable success. Tuy Hoa any day over the Golf Course. From Tuy Hoa we flew south down the coast line to Cam Ranh, then the short hop to Nha Trang.

* * *

The next day Colonel Passarello was involved in a check ride, and I flew with another pilot, Major Aubrey Milstead. Our mission took us to two more fields I hadn’t seen, Phan Rang and Dalat. Major Milstead flew most of the legs in the left seat, while I played copilot. I was happy to sit and watch.

Our first leg took us from Nha Trang to Phan Rang, home of an F-100 unit and a B-57 unit as well. Phan Rang had a long concrete runway that was necessary for jet aircraft operations. Directed to make a right-hand pattern and land to the north, we flew a normal approach. A lovely, wide river wound its way past just south of the field. On either side of the river, there was rich forest growth, and beyond, to the west, a ridge of hills. As we taxied in, the tower operator asked if we were all right.

“What do you mean, all right?” we asked.

“There was some ground fire coming up at you on final. You guys took it out a little too far. Always turn inside the river when you land to the north. We don’t own the real estate south of the river.”

At Phan Rang we loaded elements of the South Vietnamese Army to carry to Phan Thiet. I had envisioned ranks of troops marching in single file into the aircraft and sitting down smartly on our seats. My mistake. What happened instead was an operation called “combat loading.” We put empty aluminum pallets down on the cargo bay floor and extended webbed straps across the compartment from one side to the other. It seemed a rather casual manner in which to accommodate infantry troops, especially compared to the way we handled American Army troops. But I soon saw why.

When the South Vietnamese Army moved, it took everything it needed, including baggage, wives, children, and the more portable livestock, chickens, pigs, and an occasional cow. The loadmasters were not pleased about the livestock. We couldn’t blame them. Animals did not take too well to flying, especially in a confined, noisy environment like that provided inside a C-130. Moving elements of the South Vietnamese Army presented a much different logistical problem than moving elements of the American Army.

After landing at Phan Thiet, we flew a short fifteen-minute flight to Dalat, another new field. The flight to Dalat was over some scenic hills and mountains. As we neared Dalat, the hills began to smooth out slightly. A small city spread out along the edges of a large lake. There were smaller lakes, then houses, large, luxurious houses, extravagant for Vietnam. It looked like a resort area.

“There has been almost no fighting here,” Milstead said. “Dalat is a summer resort area for the wealthier citizens of Saigon. The climate is relatively cool and pleasant. It rains regularly, which combined with the cooler climate, results in an area that produces a phenomenal amount of produce. This area is South Vietnam’s vegetable garden. We come in here frequently, and our load is almost always fruits and vegetables.”

The runway tilted uphill slightly to the west; as we landed I looked to my right into a large, apparently abandoned house that sat abeam the east end of the runway. Milstead landed the aircraft easily and taxied into the ramp area. We parked close behind another C-130 on the small ramp. In addition to the two C-130s, there was an Army Beech Baron, an Air America Turbo Porter, a South Vietnamese C-47, and a couple of O-1 aircraft fitted snugly around us. The base operations building, if that’s what it could be called, was a house with a small porch on the west side overlooking the ramp. Fork lifts loaded us with pallets of bananas, pineapples, lettuce, and tomatoes while we sat on the shaded porch and drank Cokes out of a Coke machine.

This was an amazing war. Gorgeous countryside. The threat of mortars. A lovely resort area. Ground fire on short final. Coke machines. Bananas and pineapples.

We flew our load of fruit and vegetables to Tan Son Nhut and turned around and came back for more. On our second run to Tan Son Nhut, we saw a formation of two A-1Es speeding in towards Bien Hoa. “Probably with the South Vietnamese Air Force,” Milstead said.

Then, as we approached the level jungle area that stretched northeast of Saigon, we saw three F-100s diving towards some indistinct area in the jungle, a spotter plane banking to the side. As each F-100 pulled out, dark objects fell towards the ground. Then a burst of fire and dark smoke. By the time we arrived, the excitement had ended; the F-100s had left, and so had the spotter plane, apparently. We circled over the site briefly, but all we could see was a thin wisp of smoke curling out of the trees near a bend in a small river. No activity on the ground, no aircraft in the area. By the time we turned on course for Saigon, even the smoke was gone. It was difficult to believe anything had happened.

The next day Passarello’s shuttle schedule was complete. We flew out just before six o’clock the following morning, taking off into the misty dawn of the South China Sea. Back in my quarters, I stood in the shower for an hour, luxuriating in the hot water and the quiet.