19.

I didn’t sleep that night. Though I was exhausted beyond belief, the best I could manage was a flickering semi-consciousness. Every time I thought I was drifting off I was pricked awake again, either by something actually pricking me, or plain old fear. Innocent’s stillness suggested he didn’t have the same problem, but I’m pretty sure Caleb, like me, just lay there through the night, willing it to end. Dawn couldn’t come too soon.

As it was, Innocent got up when it was still dark, just. I don’t know how he judged it so well, but by the time we’d bustled ourselves ready the first bluish hint of morning was filtering down to us. I was famished and parched and my feet were sore in my boots when we set off downhill in search of the river. Innocent explained as we walked that countless streams and rivers criss-cross the jungle, thousands of strands of water weaving into tributaries that eventually knit into the mighty Congo itself. We would pick one up nearby, drink, and follow it north; apparently this stream cut quite close to our base camp in the end. He was trying to take our minds off the pain of getting going again, I know. I did the same by imagining the statistics – rainfall measurements, humidity levels, that sort of thing – Amelia would no doubt have contributed if she’d been with us. I hoped she and the others had made it back to camp OK and slept better than us.

We reached the river soon enough. It was more of a stream really, not more than ten feet wide. The ground either side of it was boggy, stabbed full of reeds, and the water itself was brown as tea, but I was so thirsty I didn’t care. Scrabbling for my empty water bottle, I started to wade in. Innocent stopped me.

‘We need to purify it first.’

The thought of waiting while we built a fire – out of what, damp sticks? – and boiled water – in what? we hadn’t brought a pan – to purify it nearly made me snap, but he smilingly held up a hand, rooted in his pack, and produced a little plastic tube.

‘Clever tablets,’ he said.

Clever, but slow: once added to our refilled water bottles the tablets took thirty agonising minutes to work, and that half an hour waiting for the water to be safe to drink was an eternity. Being as parched as that made me realise I’d never actually experienced proper thirst before. Even when I’d thought I was thirsty after sport, say, I wasn’t really: my entire life, when I’ve wanted water to drink, I’ve been able to turn on a tap within minutes. I’d only gone, what, twelve hours without a drink now, but I’d been sweating in the humidity and the thirst I battled as I sat waiting for that tablet to work tasted like ash and headaches, sawdust and scabs. Innocent himself seemed perfectly content to wait, but I could tell Caleb was hurting too. Though he didn’t say so, I saw him looking at his watch and he caught me looking at mine. Perversely, when the thirty minutes were up, I held back from taking the top off my bottle. So did Caleb. Innocent took a sip from his own flask but we both waited. I didn’t fully understand why to begin with, though it was perfectly obvious. Neither of us wanted to crack first. As soon as I spelled that stupidity out to myself I said, ‘Ridiculous,’ unscrewed the lid, and drank half the bottle in one go. I’m pretty sure I caught Caleb smiling before he followed suit.

Purification tablets make water taste of chlorine, like a swimming pool, and there was grit in my bottle, and the water was lukewarm, but just as Innocent’s boiled sweet had been the best I’d ever eaten, that was the most welcome drink of my life. Everything – even my sore feet – felt better after it. The water evidently rebooted Caleb too. ‘Come on then, we should make tracks,’ he said, bouncing on the balls of his feet. This show of readiness was unnecessary as Innocent and I were already primed to go. But Caleb obviously wanted to assert that he was in charge, so not content with having chivvied us pointlessly, he set off into the jungle, swinging his machete this way and that, a self-appointed expedition leader.

The only trouble was that he’d started out in the wrong direction again. It’s hard to navigate in the jungle, I know, but we were supposed to follow the stream north, meaning the morning sun would be coming from our right, and Caleb had set off with the sun to our left. After he’d taken a few steps I glanced at Innocent, first to make sure I hadn’t gone mad, and second because I didn’t want to be the one to correct him. I’m pretty sure Innocent shot me a smile.

‘Mr Caleb!’ he sang.

Caleb, who was thirty metres upstream and already just about out of sight, shouted, ‘What are you waiting for?’

Innocent took a deep breath to tell him, but before he could there was a rush of leaves and a yelp-scream and what we could see of Caleb through the foliage suddenly changed shape. Both of us sprinted towards him. On arrival, it seemed as if he’d collapsed mid-cartwheel. One of his green boots was wrenched awkwardly above his head, still firmly attached to his foot, beneath which the rest of him was writhing on the ground. He’d stepped in a snare. I was surprised to find myself genuinely worried he’d been hurt. But his ‘Get me down!’ was angry rather than agonised.

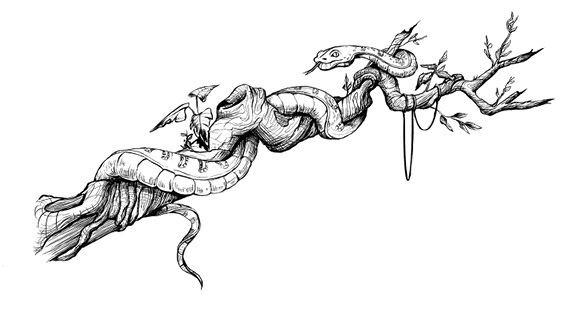

Caleb’s machete was on the ground in front of me. The snare was made out of a loop of paracord rigged to a log, itself cantilevered over a bent tree. I couldn’t quite work out the mechanics of the thing, but if how to set Caleb free? was the question, sever the rope had to be the answer. I fired off a quick photo for the record while Caleb was looking towards Innocent, then picked up the big knife and swung it at the knot: the log thumped to the ground, the treetop snapped upright and Caleb’s leg joined the swearing rest of him on the floor.

‘You OK?’ Innocent sounded concerned: did he think Caleb was about to blame him?

‘Of course I’m OK.’ Caleb brushed himself down. ‘I just …’ He trailed off. For a half-beat I thought he might be about to laugh: since he wasn’t injured, surely he could see the funny side? But his face hardened and aside from muttering a brusque, ‘Thanks,’ as I handed him back his knife it was pretty clear ‘funny’ wasn’t on his radar.

‘Dangerous, horrible,’ said Innocent, holding up the snare. ‘Many animals die this way. They do not have a friend to cut them down.’

‘I’d have freed myself eventually,’ Caleb muttered.

He might well have done so – the machete was probably within his reach – yet his lack of gratitude was irritating. I tried not to respond. But once he’d picked the leaves out of his hair and was ready to go again, I couldn’t help pointing back downstream and saying, ‘Right then, shall we head in the actual direction of the others this time?’ with a fake lightness in my voice. I wish with all my heart that I’d held my tongue; if I’d stopped myself from goading him, we might have avoided the awfulness of what happened later.