Figure 1. Diagram representing spatially the ontological relation of, and the interactions between, God and the world (including humanity).

Insurers used to describe inexplicable, unpredictable, unexpected events as ‘acts of God’, and if these were favourable to their purposes or health, individuals would often describe them as ‘miracles’. This serves to emphasise the confusion and obscurity that surround the whole question of how and whether God acts in the world. We have already seen (p.56) why the intellectual pressure of the scientific account of the world makes it increasingly incredible, even to theists, that God would actually intervene in the causal nexus of the world that God’s own self creates.

To these earlier considerations, based on the increasing success of the sciences in accounting for natural events, must be added the moral dilemma that, if God can and does intervene in events in the world, why is evil allowed to flourish? All of this arises from the notion of ‘acts’ of God in which God is supposed to ensure that certain particular events, or patterns of events, occur when otherwise they would not have done so. But such acts are not the only ways in which God has been thought to interact with the world. We have, for example, already talked of God as giving existence to all-that-is by an act of God’s own will and as the expression of God’s own nature. This is what the classical monotheist affirmation of creatio ex nihilo, ‘creation out of nothing’, was about. We have also seen cause (pp.65ff.), from the epic of evolution, to regard God as the eternal Creator sustaining in existence processes that are endowed by God with an inherent capability to generate new forms and so with possessing a derived creativity. Classically, monotheists have regarded this as the sustaining activity of God. In the past this was conceived of in somewhat static terms, seeing God rather like the figure of Atlas supporting the terrestrial globe. However, in view of the epic of creation, this now has to be clothed with much more dynamic imagery. God gives existence to each instance of space–time with all forms of matter–energy themselves dynamically and continuously and creatively being metamorphosed into new entities, forms and patterns. These latter have included ourselves – all human beings and their societies and history. From this human perspective, the sustaining creative interaction of God with the world has often been called God’s ‘general providence’. The scientific vision we now possess reinforces and enriches this understanding of God’s creating and sustaining interactions with the world.

This is not the case when we consider the possibility of particular events, or patterns of events, being other than they would naturally have been because God intended them to be different. Such possibilities have often been denoted as the ‘special providence’ in God’s interaction with the world – the outcomes of special divine action. This category can be extended to include miracles, regarded as events not conforming to natural regularities believed to be well established. Indeed the followers of the monotheistic faiths, the ‘children of Abraham’ – Jews, Muslims and Christians – shape their lives and religious practices on the general belief that God does indeed influence people and events. Private devotions and public liturgies in these religious traditions include much else of spiritual significance (for example, thanksgiving, adoration, contemplation, meditation). Yet they certainly involve an inexpungeable element of petitionary prayer which is based on the belief that God can make particular events happen if God so wills. Nevertheless, in contrast, a ‘presumption of naturalism’ – no supernatural causes, no intervening God – prevails in the present cultural milieu in which the monotheistic religions, especially Christianity in the West, operate. That milieu is dominated by the success of the sciences in explaining not only physical events but also human psychological and social ones – the whole epic of evolution from the ‘hot big bang’ to humanity has become intelligible in scientific terms.

This presumption in favour of intelligible, scientific explanations is reinforced by its methodological necessity in our investigations of the world and by the emergentist monist position we established earlier (pp. 48ff.). We argued there that all-that-is, the ‘world’, is made up of whatever physicists conclude are the basic building blocks of matter. Although there is nothing else in the world in one sense, nevertheless there is more to be said than such a statement seems to imply. As we saw, there are hierarchies of complexity constituted of those fundamental entities and these complexes display emergent properties that can have causal efficacy on lower levels. So they represent higher-level realities than those fundamental ones. There is, we recognised, no grounds for any kind of supernaturalism, non-natural causal agents, vital forces (the ghosts of discarded vitalisms), any of the ‘fields’ modern occultisms postulate or even for mind/body or spirit/body duality in human beings.

It is this basically monistic, but many-levelled and so emergentist, world with which God must be seen to be interacting. Such is the success of the sciences that it is very hard to see how God, in principle, could affect patterns of events in the world without actually intervening in the natural, causal chains of events. If so, then how are we to conceive of God’s special divine action, of a form of God’s interaction with the world that influences, steers or even directs events to be other than they would have been had not God particularly willed them to be so? The presumption of naturalism has tightened into the realisation that the causal nexus of the world is increasingly perceived as closed. There would seem to be no way for God to affect events other than by direct intervention in causal chains or providing new environing structural causes. This remains in principle a possibility, since God could bring about events in the world by simply overriding the divinely created relationships and regularities. That is always a theoretical, though incoherent, possibility for the monotheist, but our present understanding of the world increases to the point of unattainability the onus on those who believe in such special providence and/or miracles to obtain convincing historical evidence for them. The more irregular and unlikely the event, the better the evidence must be. Moreover, it is not sufficient for an event to be inexplicable by current science, for science has continuously closed the gaps in our knowledge and understanding of the world. Any ‘God of the gaps’ is vulnerable to being squeezed out by increasing knowledge, as is widely recognised by theologians.

Given this cultural and intellectual impasse in our ability to conceive of how God could interact with the world through special providence and/or miracles, it is not surprising that this has been a key issue in the quickening pace of the dialogue between science and theology in the last two decades. At the spearhead of this attempt to relate our knowledge of the natural world to received theological beliefs, especially in regard to this issue, have been the biennial research symposia instigated since 1987 by the Vatican Observatory with the cooperation of the Center of Theology and the Natural Sciences in Berkeley, California. The scientists, theologians and philosophers (often embodied in the same individuals) have, beginning with Physics, Philosophy and Theology: A Common Quest for Understanding (1998), produced since then a succession of state-of-the-art volumes about scientific perspectives on divine action. These have been focused on different areas of the sciences: quantum cosmology and the laws of nature; chaos and complexity; evolutionary and molecular biology; and neurosciences and the person. These, with more general texts, should be consulted to follow the ebb and flow of the discussions.1 It cannot be pretended that consensus has yet been obtained but the nature of the problems and the strengths and weaknesses of various proposals have been and continue to be thoroughly examined.

Meanwhile popular Christianity continues to affirm the miraculous nature not only of certain events recorded in the Bible, but even some events in everyday life. It does so without recognising the incoherence and insupportability of such beliefs in a cultural milieu more critically informed of the nature of the world than in the previous generation – light years from the presuppositions of the biblical and Koranic texts. This style of belief will no doubt persist in many circles, but meanwhile the educated in Western Europe, at least, vote with their feet in absenting themselves from the churches. At present this is an especially acute issue for Christianity (and possibly Judaism), which has borne the brunt of the Enlightenment critique of its sacred sources and of the effect of the widening perspectives through science of the origin and evolution of nature, especially humanity. Other major religions have yet to experience an equivalent awakening to rational criticism.

I have elsewhere (for example, in the volumes just referred to) expounded in detail my own reflections on God’s interaction with the world from the perspectives of the sciences, and my detailed analysis of the reflections of others. In what follows I will summarise for the general reader where I think the discussions have led and state my own position on these controversial issues. I shall not conceal my conviction that certain routes of exploration, albeit followed by very able investigators, have proved to be culs-de-sac and I shall point out the lines of enquiry that I judge still to be fruitful. Part of the underlying problem in such investigations is the general, and often vague, assumption that science has somehow ensured that events in the world are predictable, and so we must first look at this background issue.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, John Donne (in his Anatomie of the World) lamented the collapse of the medieval synthesis – ‘Tis all in pieces, all cohaerance gone’ – but after that century nothing could stem the rising tide of an individualism in which the self surveyed the world as subject over against object. This way of viewing the world involved a process of abstraction in which the entities, structures and processes of the world were broken down into their constituent units. These parts were conceived as wholes in themselves, whose lawlike relations it was the task of the ‘new philosophy’ to discover. It may be depicted, somewhat oversuccintly, as asking, firstly, ‘What’s there?’, then, ‘What are the relations between what is there?’ and finally, ‘What are the laws describing these relations?’ To implement this aim a methodologically reductionist approach was essential, especially when studying the complexities of matter and of living organisms. The natural world came to be described as a world of entities involved in lawlike relations that determined the course of events in time and so allowed predictability.

The success of these procedures has continued to the present day, in spite of the revolution necessitated by the advent of quantum theory in our understanding of the subatomic world. On the larger scales that are the focus of most of the sciences, from chemistry to population genetics, the unpredictabilities of quantum events at the subatomic level are usually either ironed out in the statistics of the behaviour of large populations of small entities or can be neglected because of the size of the entities involved, or both. Predictability was expected in such macroscopic systems and, by and large, it became possible after due scientific investigation. However, it has turned out that science, being the art of the soluble, has until recently tended to concentrate on those phenomena most amenable to such interpretations.

The world is notoriously in a state of continuous flux. As Heraclitus said in the fifth century BCE, ‘Nobody can step twice into the same river.’ It has, not surprisingly, been one of the major preoccupations of the sciences ever since to understand the changes that occur at all levels of the natural world. Science has asked, ‘What is going on?’ and ‘How did these entities and structures we now observe get here and come to be the way they are?’ The object of curiosity was both causal explanation of past changes in order to understand the present and also prediction of the future course of events, of changes in the entities and structures that concern us.

The notions of explanation of the past and present and predictability of the future are closely interlocked with the concept of causality. Detection of a causal sequence in which, say, A causes B, which causes C, and so on, is frequently taken to be an explanation of the present in terms of the past. It is also predictive of the future, insofar as observation of A gives one grounds for inferring that B and C will follow as time elapses, since the original A–B–C sequence was itself a succession in time. It has been widely recognised that causality in scientific accounts of natural sequences of events can only reliably be attributed when some underlying relationships of an intelligible kind have been discovered between the successive forms of the entities involved. The fundamental concern of the sciences is the explanation of change, and so with predictability and causality. It transpires that different kinds of natural systems display various degrees of predictability and that the corresponding accounts of causality are therefore different.

Science began to gain its great ascendancy in Western culture through the succession of intellectual pioneers in mathematics, mechanics and astronomy which led to the triumph of the Newtonian system with its explanation not only of many of the relationships in many terrestrial systems but, more particularly, of planetary motions in the Solar System. Knowledge of both the governing laws and the values of the variables describing initial conditions apparently allowed complete predictability of these particular variables. This led, not surprisingly, considering the sheer intellectual power and beauty of the Newtonian scheme, to the domination of this criterion of predictability in the perception of what science should, at its best, always aim to provide – even though single-level systems such as those studied in both terrestrial and celestial mechanics are comparatively rare. It also reinforced the notion that science proceeds, indeed should proceed, by breaking down the world in general, and any investigated system in particular, into their constituent entities. So it led to a view of the world as mechanical, deterministic and predictable. The concept of causality in such systems can be broadly subsumed into intelligible and mathematical relations with their implication of the existence of something analogous to an underlying mechanism that generates these relationships. Furthermore certain properties of a total assembly can sometimes be predicted in more complex systems. For example, the gas laws are not vitiated by our lack of knowledge of the direction and velocities of individual molecules.

It is well known that the predictability of events at the atomic and subatomic level has been radically undermined by the realisation that there is a fundamental indeterminacy in the measurement of certain key quantities in quantum mechanical systems. It arises from there being only a probabilistic knowledge of the outcome of the collapse of the wave function which occurs when measurements are made. This introduces an inherent limitation, in some respects though not all, in the predictability of the future states of such systems. A related example of such inherent unpredictability occurs, as we have seen (p.58), for any collection of radioactive atoms. It is never possible to predict at what instant the nucleus of any particular atom will disintegrate – all that can be known is the probability of it breaking up in a given time interval. This exemplifies the current state of quantum theory, which allows only for the dependence on each other of the probable measured values of certain variables and so for a looser form of causal coupling at this micro-level than had been taken for granted in classical physics. But note that causality, as such, is not eliminated.

However, there are also Newtonian systems that are deterministic yet unpredictable at the micro-level of description. This has been a timebomb ticking away since the 1900s under the edifice of the deterministic, and so predictable, paradigm of what constitutes the worldview of science. The French mathematician Henri Poincaré then pointed out that the ability of the (essentially Newtonian) theory of dynamical systems to make predictions depends on knowing not only the rules for describing how the system will change with time, but also the initial conditions of the system. Predictability often proved to be extremely sensitive to the accuracy of our knowledge of the variables characterising those initial conditions. Thus it can be shown that even in assemblies of bodies obeying Newtonian mechanics there is a real limit to the period during which the micro-level description of the system can continue to be specified, that is, there is a limit to predictability at this level. This limit has been called the horizon of ‘eventual unpredictability’. We cannot achieve unlimited predictability, because of our inability ever to determine the initial conditions with sufficient precision, in spite of the deterministic character of Newton’s laws.

For example, in a game of billiards, suppose that, after the first shot, the balls are sent in a continuous series of collisions, that there are a very large number of balls and that collisions occur with a negligible loss of energy. If the average distance between the balls is ten times their radius, then it can be shown that an error of one in the thousandth decimal place in the angle of the first impact means that all predictability is lost after one thousand collisions. Clearly, infinite initial accuracy is needed for total predictability through infinite time. The uncertainty of the directions of movement grows with each impact as the originally minute uncertainty becomes amplified. So, although the system is deterministic in principle – the constituent entities obey Newtonian mechanics – it is never totally predictable in practice.

Moreover, it is not predictable for another reason, for even if the error in our knowledge of the angle of the first impact were zero, unpredictability still enters because no such system can ever be isolated completely from the effects of everything else in the universe – such as gravity and the mechanical and thermal interactions with its immediate surroundings.

Furthermore, attempts to specify more and more finely the initial conditions will eventually, at the quantum level, come up against the barrier of the measurement problem against our knowledge of key variables characterising the initial conditions even in these ‘Newtonian’ systems. So new questions arise. Does this limitation on our knowledge of these variables pertaining to individual units (whether atoms, molecules or billiard balls) in an assembly reduce the period of time within which the trajectory of any individual unit can be traced? Is there an ultimate upper limit to the predictability horizon set by the irreducible quantum fuzziness in the values of those key initial conditions to which the eventual states of these systems are so sensitive? Does eventual unpredictability prevail with respect to the values of those same parameters that characterised the initial conditions and to which quantum uncertainty can apply? Many physicists think so.

One of the paths taken in the exploration from science towards an understanding of divine action has been to consider ‘chaotic’ systems. One of the striking developments in science in recent years has been the increasing recognition that many other non-quantum systems – physical, chemical, biological and neurological – can also become unpredictable in their macroscopically observable behaviour. This is so even when the course of events is governed by equations that are deterministic in their consequences so that the final states are determined. Basically the unpredictability to human observers arises because two states of the systems in question which differ only slightly in their initial conditions eventually generate radically different subsequent states and we are unable to measure the significant differences in those initial conditions. These are generally, and somewhat misleadingly, called ‘chaotic’ systems. One particular equation (the so-called ‘logistic’ equation) has proved to be significant for a number of natural systems, e.g. predator–prey patterns, yearly variation in insect and other populations, and physical systems too. In some other systems there can occur an amplification of a fluctuation of the values of particular variables (e.g. pressure, concentration of a key substance, etc.) so that the state of the system as a whole undergoes a marked transition to a new regime of patterns of these variables. The state of such systems is then critically dependent on the initial conditions that prevail within the key transitory fluctuation which is subsequently amplified. A well-known example is the ‘butterfly effect’ of Edward Lorenz, whereby a butterfly disturbing the air here today could affect what weather occurs on the other side of the world in a month’s time through amplifications cascading through a chain of complex interactions. Another is the transition to turbulent flow in liquids at certain combinations of speed of flow and external conditions. Yet another is the appearance, consequent upon localised fluctuations in reactant concentrations, of spatial and temporal patterns of concentration of the reactants in otherwise homogeneous systems when these involve autocatalytic steps – as is often the case, significantly, in key biochemical processes in living organisms. It is now realised that the time sequence of the values of key parameters of such complex dynamical systems can take many forms: limit cycles, regular oscillations in time and space, and flipping between two alternative allowed states.

In the real world most systems do not conserve energy: they are usually dissipative ones (p.52) through which energy and matter flow, and so are also ‘open’. Such systems can often give rise to the kind of sequence just mentioned. Moreover, recent physics has also led to the recognition that, in such changeovers to temporal and spatial patterns of system behaviour, we have examples of the self-organisation mentioned earlier (pp.52, 69). New patterns of the constituents of the system in space and time become established when a key parameter passes a critical value.

Explicit awareness of all this is relatively recent in science and necessitates a reassessment of the potentialities of the stuff of the world, in which pattern formation had previously been thought to be confined to the large-scale, static, equilibrium state. In these recently examined systems, matter displays its potential to be self-organising and thereby to bring into existence new forms entirely by the operation of forces and the manifestation of properties we already understand. ‘Through amplification of small fluctuations it [nature] can provide natural systems with access to novelty.’2

How do the notions of causality and predictability relate to our new awareness of these phenomena? (We shall discuss this without taking account of quantum uncertainties.) Causality, as usually understood, is clearly evidenced in the systems just discussed. Nevertheless, identification of the causal chain now has to be extended to include unobservable fluctuations at the micro level whose effects in certain systems may extend through the whole system so as to produce effects that extend over a spatial range many orders of magnitude greater.

The equations governing all these systems are deterministic, which means that if the initial conditions were known with infinite precision, prediction would be valid into the infinite future. But it is of the nature of our knowledge of the real numbers used to represent initial conditions that they have an infinite decimal representation and we can know only their representation up to a certain limit. Hence there will always be, for systems whose states are sensitive to the values of the parameters describing their initial conditions, an ‘eventual unpredictability’ by us of their future states beyond a certain point. The ‘butterfly effect’, the amplification of micro-fluctuations, turns out to be but one example of this. In such cases the originating fluctuations would anyway be inaccessible to us experimentally. Note, however, that – after much discussion – it has become clear that although these states are unpredictable by us they are not intrinsically (more technically, ‘ontologically’) indeterminate, in the way that quantities dependent on quantum states and sensitive to measurement indeterminacy are taken to be, in the prevailing orthodox interpretation of physicists. Nevertheless, this whole scientific development does show that there can exist states of particular systems that are extremely close in energy, yet differ in their pattern or organisation and so in information content.

In spite of the excitement generated by this recently won awareness of the character of the systems described above, the basis, in practice, of the unpredictability of their overall states is, after all, no different from that of the eventual unpredictability at the micro level of description of classical Newtonian systems. However, the world appears to us less and less to possess the predictability that had been the presupposition of much theological reflection on God’s interaction with the world since Newton. We now observe it to possess a degree of openness and flexibility within a lawlike framework, so that certain developments are genuinely unpredictable by us on the basis of any conceivable science. We have good reasons for saying, from the relevant science and mathematics, that this unpredictability will, in practice, continue.

The history of the relation between the natural sciences and the Christian religion affords many instances of such gaps in human ability to give causal explanations – that is, instances of unpredictability – being exploited by theists as evidence of the presence and activity of God, deployed to fill the explanatory gap. But now we have to take account of permanent gaps in our ability to predict events in the natural world. Should we propose a ‘God of the (to us) uncloseable gaps’? There would then be no possibility of such a God being squeezed out by advances in scientific knowledge. This raises two questions of theological import:

With respect to the first question,3 an omniscient God may be presumed to know not only all the relevant, deterministic laws that apply to any system, but also the relevant initial values of the determining variables to the degree of precision required to predict its state at any future time, however far ahead, and also the effects of any external influences from anywhere else in the universe, however small. So, for those systems whose future states are sensitive to the initial conditions, there would be no eventual unpredictability for an omniscient God, even though there is such a limiting horizon for finite human beings because of the nature of our knowledge of real numbers and because of ineluctable observational limitations. Divine omniscience must, for example, be conceived to be such that God would know and be able to track the minutiae of those fluctuations in dissipative systems which are unpredictable and unobservable by us and whose amplification leads at the large-scale level to one particular outcome rather than another – but still unpredictable by us. God would just know all that it is logically conceivable to know about the systems (initial conditions, controlling equations, etc.), indeed knows them as they deterministically are, and so knows what they will be – even if the future does not yet exist for God to know with direct immediacy (p.45).

This is an affirmative answer to our first question. Could we then go on to postulate that God might choose to influence events in such systems by changing those initial conditions so as to bring about a different macroscopic consequence conforming to the divine will and purposes? This would be also to answer question two affirmatively. God would then be conceived of as acting ‘within’ the (to us) flexibility of these unpredictable situations in a way that, in practice, we could never detect. Such a mode of divine action would always be consistent with our scientific knowledge of the situation. In the significant case of those dissipative systems whose macro-states arise from the amplification of fluctuations at the micro level, God would have to be conceived of as actually manipulating micro-events in these initiating fluctuations in the natural world in order to produce the results at the large-scale level that God wills.

Such a conception of God’s action in these, to us, unpredictable situations would then be no different in principle from that of God intervening in the order of nature, with all the problems that that evokes for a rationally coherent belief in God as the Creator of that order. The only difference in this proposal from that of earlier ones postulating divine intervention would be that, given our recent recognition of the actual unpredictability, on our part, of many natural systems, God’s intervention would always be hidden from us. Discussion of these systems has, however, served to emphasise how, in the limit,4 ‘chaotic’ systems may become very close in energy (perhaps even within the quantum range) but different in pattern and so in information content. But at present there is no theory available to deal with such ‘quantum chaos’ and there is therefore no basis for pursuing this as a line of investigation which might help us to understand special divine action.

At first sight this introduction of unpredictability, open-endedness and flexibility into our picture of the natural world seemed to help promise a possible location for where God might act in the world in now uncloseable ‘gaps’. However, the above considerations indicate that such divine action would be simply the kind of divine intervention which we were striving to avoid postulating. Note, too, that this analysis continues to assume that God can know all it is logically possible to know about natural events, that God is omniscient and so does know the outcome of deterministic natural situations which are unpredictable to us.

All of this leads us to the conclusion that this newly won awareness of the unpredictability, open-endedness and flexibility inherent in many natural processes and systems does not, of itself, help directly to illuminate the causal joint of where God acts in the world – much as it alters our understanding of what is going on. This route for understanding special divine action based on our scientific perceptions has therefore proved to be a cul-de-sac. But even dead ends have their uses and the exercise has demonstrated how open for us are the outcomes of many scientifically understood processes and that we are wise not to assume our total ability always to be able to predict the outcome of situations where there are many alternative states, structures and sequences of events that are very close in energy but differ in pattern and so in their information content.

Another route in the exploration towards an understanding of divine action in the light of the sciences, which has again been followed in recent discussions among scientists and theologians, and those who are both, is the possibility that the indeterminacy of the outcomes of measurements at the quantum level might provide another possible uncloseable gap in the causal chains of nature. This indeterminacy is regarded as inherent, irremovable and basic by most physicists. They do not believe there are hidden variables to be discovered to render quantum events deterministic. In such an unclosable gap at the quantum level, God, it is proposed, could be affecting the outcomes of particular events consistently with the laws of the relevant science (quantum mechanics in this case) and unbeknown to human observers. Although some proponents of this view have argued for God being active in all quantum events, others postulate divine action only in some – and preferably those whose consequences are amplified to larger-scale levels, for example by ‘chaotic’ processes, and/or in dissipative systems. This last kind of proposal is particularly attractive, seductive even, insofar as it can be propounded as the means whereby God might affect the course of biological evolution and even of human thinking – by divine action at the quantum level of mutations in DNA and on neuronal synapses, respectively. So it is not surprising that this hypothesis has attracted weighty supporters. Those making this kind of proposal all accept, with most physicists, the inherent, ontological indeterminancy of the outcomes of particular quantum events – more precisely, of the outcomes of measurements at the quantum level. They recognise that there can be only a probabilistic advance knowledge of certain key parameters of a quantum mechanical system which would result from measurements made upon it. The state of such a system, according to the most widely accepted view, is represented before the measurement by a superposition of wave functions, which then collapses into a single one after it. Which one it will collapse into, which state the system will then be in, can be known in advance only probabilistically and no other more precise, advance knowledge is possible – in principle, most physicists would add. That is the force of the adverb ‘ontologically’ when it precedes ‘indeterminate’ and is applied to such situations.

Those who argue for direct divine involvement in all such quantum events, in all such wave-function collapses, are – such is the basic underpinning of all natural events at the quantum level – really, it seems to me, implicitly supporting total direct divine determination of all events. This is a form of the theological view called ‘occasionalism’ and entails notorious problems concerning evil and free will, among many others. So the most defensible form of this hypothesis is that which proposes that God influences directly the outcomes of only some quantum events, in particular those whose outcomes can be amplified to bring about specific effects at larger-scale levels.

All involved in this discussion, whether or not in agreement with the proposals just outlined, accept that God upholds and sustains, gives continuous existence to, those processes and events in the natural world for which quantum mechanics is the current best (and indeed highly successful) interpretation. That is not the issue. What is in dispute is whether or not more direct and particular divine action needs to be postulated at this lowest structural level of known nature. However qualified, this cannot but be regarded as an intervention of the kind about which we have the general grounds for scepticism already given. These were, briefly, that any model of God directly, specifically and intermittently determining particular outcomes of processes already established scientifically is inconsistent with one of the key emphases that the recent dialogue between the sciences and theology has been found to deliver. This is that the processes of the natural world have an inherent rationality, consistency and creativity in themselves which gives rise to novelty, diversity and complexity – thereby pointing to the very nature of the God who creates them, all the time sustaining them in their existence of that kind. The assumption of the above hypothesis that God acts to alter the probability, or the actual outcome, of wave-function collapses would still be a hands-on intervention by God in the very processes to which God has given existence. This would still be so even if we could never, in practice or in principle, detect this divine action. It would imply that these processes without such intervention were inadequate to effect God’s creative intentions if they continued to operate in the, usually probabilistic, way God originally made them and continues to sustain them in existence.

These are general criticisms of all such hypotheses of divine intervention, but in the case of the proposed quantum-level intervention, there are further specific problems to be faced. If one does not assume, with most physicists, that there are hidden variables really determining events, then the outcomes of measurements on quantum-mechanical systems really are ontologically indeterminate, within the restrictions of the deterministic equations governing the development of the state of the system in time.5 These equations govern only the probabilities of the outcome of measurements. Since God can know only what it is logically possible to know (‘omniscience’) and that is confined to the probabilities of the outcome of any measurement, God cannot, logically cannot, know definitively the precise outcome of any particular measurement. Furthermore, if God were to alter one such event in a particular way, then, for the overall probabilistic relationships that govern the quantum events to be obeyed, many others – absurdly many – would also have to be changed. Only thus would we, the observers, detect no distortion of the overall statistics, as the hypothesis assumes. So this is certainly no neat, tidy way to solve the problem and one wonders where the chain of necessary alterations would end. Indeed, to determine microscopic events on any terrestrial scale, God would have to determine a fantastically large number of quantum processes over extraordinary long periods in advance. As Nicholas Saunders has put it,

[I]magine God wishes to annihilate the dinosaurs by colliding an asteroid into the face of the Earth. If by coincidence an asteroid happened to be ‘naturally’ going to just skim the Earth’s atmosphere then God could steer it into the Earth for a collision by using quantum adjustments. Such a steering would take approximately three million years to achieve if no violations of physical laws occurred. This implies that God would have had to start steering the asteroid long before the evolution of the dinosaurs. Whilst this is a theologically unsatisfactory model (not least because it ignores the possibility of divine action on any part of creation other than the asteroid) it does go some way to illustrating the scale of the control God must employ. If God does act regularly in quantum mechanics, then there are relatively few quantum processes that would escape his control. If this is the case then it seems very irrational that God would formulate quantum mechanics as a product of his creation of the world to be indeterminate.6

Even more critical issues about the ‘quantum divine action’ proposals arise when one asks how God can actually influence the outcomes of quantum events, more precisely, the outcomes of measurements on quantum-mechanical systems, some of which could then be amplified to the macroscopic level of observable events.

Telling scientific arguments have in fact been assembled by Nicholas Saunders (and others, see note 6) which show that these proposals are also not consistent or coherent in terms of quantum theory itself. (The arguments are summarised in an endnote7 to this chapter for readers acquainted with quantum theory.) His conclusion is:

The thesis that God determines all quantum events is not only scientifically irreconcilable with quantum theory, but also theologically paradoxical. There are also fundamental philosophical difficulties to be overcome if we hold to the thesis that God influences only some events at a quantum level. Moreover the scale of the providence which is required for divine action through quantum mechanics is truly phenomenal – it takes millions of years of action to achieve even the most simple effects. If it is also held that human beings have free will then this situation becomes absurd. By making quantum measurements we are determining the state of divine quantum determinations in a way that must significantly increase the already considerable amount of time God requires to achieve anything. The linking of divine action to quantum mechanics must take place by some kind of measurement interaction and this also places God in a subordinate position to creation and the episodicity of measurements places severe limitations on the possible actions God could achieve. The resulting view of divine action is far from the Biblical and traditional accounts of providence and it thus seems reasonable to conclude that a theology of divine action that is linked to quantum processes is theologically and scientifically untenable.

This verdict seems to me to be correct for the foreseeable future unless some unexpected radical changes occur in the widely accepted understanding of quantum mechanics on which the foregoing has been based.

Let us now investigate what I consider to be a more promising path in our exploration towards understanding the interaction of God with the world, one that the sciences of the last century of the second millennium have opened up.

We have seen (p.51) that causality in complex systems made up of units at various levels of interlocking organisation can best be understood as a two-way process. There is clearly a bottom-up effect of the constituent parts on the properties and behaviour of the whole complex. However, real features of the total system-as-a-whole are frequently an influence upon what happens to the units (which may themselves be complex) at lower levels. The units behave as they do because they are part of these particular systems. What happens to the component units is the joint effect of their own properties, explicable in terms of the lower-level science appropriate to them, and also the properties of the system-as-a-whole which result from its particular organisation. When that higher level can also be understood only in terms not reducible to lower-level ones, then new realities having causal efficacy can be said to have emerged at the higher levels.

We have also seen (pp.54ff.) that the world-as-a-whole may be regarded as a kind of overall System-of-systems, for its very different (e.g. quantum, biological, cosmological) components systems are interconnected and interdependent across space and time, with wide variations in the degree of coupling. There will therefore be an influence on the component unit systems, at all levels, of the states and patterns of this overall world-System and of its succession of states and patterns. Moreover, God, by God’s own very nature as omniscient, is the only being that could have an unsurpassed awareness of such states and patterns of the world-System in all its interconnectedness and interdependence. These would be totally and luminously clear to an omniscient God in all their ramifications and degrees of coupling across space and time. For God is present to and constitutes the circumambient Reality of all-that-is – that is what is meant by my emphasis on the immanence of God and what panentheism is all about.

I want now to explore the possibility that these theological insights informed by new scientific perspectives might provide a resource for exploring how we are to conceive of God interacting with the world. Let me make it clear from the outset that I am not postulating that the world is ‘God’s body’, for, although the world may best be regarded as ‘in’ God (panentheism), God’s Being is distinct from all created beings in a way that we are not distinct from our bodies. Yet, although the world is not organised like a human body, it is nevertheless a system, for all-that-is displays real interconnectedness and interdependence. So we shall continue to speak of the ‘world-System’ without relying, at this stage, upon any analogy with the mind–brain–body relation or with personal agency.

If God interacts with the world-system as a totality, then God, by affecting its overall state, could be envisaged as being able to exercise influence upon events in the myriad sublevels of existence of which it is made without abrogating the laws and regularities that specifically apply to them. Moreover, God would be doing this without intervening within the supposed gaps provided by the in-principle, inherent unpredictabilities noted earlier (p.58). Particular events could occur in the world and be what they are because God intends them to be so, without any contravention of the laws of physics, biology, psychology or whatever is the pertinent science for the level in question – as in the exercise of whole–part influence within the many constituent systems of the world.

This model is based on the recognition that an omniscient God uniquely knows, over all frameworks of reference of time and space, everything that it is possible to know about the state(s) of the world-System, including the interconnectednesss and interdependence of the world’s entities, structures and processes. By analogy with the operation of whole–part influence in real systems, the suggestion is that, because the ontological gap between the world and God is located simply everywhere in space and time, God could affect holistically the state of the world-System. Thence, mediated by the whole–part influences of the world-system on its constituents, God could cause particular patterns of events to occur which would express God’s intentions. These latter would not otherwise have happened had God not so specifically intended.

Any such interaction of God with the world-System would be initially with it as a whole. One would expect this initial interaction to be followed by a kind of ‘trickle-down’ effect as each level affected by the particular divine intention then has an influence on lower levels and so on down the hierarchies of complexity to the level at which God intends to effect a particular purpose. We have already seen (p.103) how in ‘chaotic’ systems, especially dissipative ones, states can differ in pattern and organisation (and so in information content) yet be very close in energy. This provides a flexible route for the transmission of divinely influenced information from the world-System as a whole down to particular systems within that whole. These could well be those of individual human-brains-in-human-bodies-in-society (pp.59ff.) and so this could be the means whereby God is experienced in acts of meditation and worship – as well as recognised as ‘special providence’ in events judged to be responses to such human acts. If such divine responses were so transmitted then they would be indirect and elusive and could well take a long time by human reckoning – which corresponds to actual religious experience. This action of God on the world is to be distinguished from God’s universal creative action in that particular intentions of God for particular patterns of events to occur are effected thereby.

The ontological interface at which God must be deemed to be influencing the world is, on this model, located in that which occurs between God and the totality of the world-System and this, from a panentheistic viewpoint, is within God’s own self. What passes across this interface may perhaps be appropriately conceived of as a ‘flow of information’ without energy transfer (as would necessarily accompany it in such flows within the world-system). But one has to recognise that there will always be a distinction, and so gulf, between the nature of God and that of all created entities, structures and processes (the notorious ‘ontological gap at the causal joint’ of Austin Farrer8). Hence this model can attempt to postulate intelligibly only the ‘location’ and tentative character of the initial effect of God on the world-System seen, as it were, from our side of the boundary. Whether or not this analogical use of the notion of information flow proves helpful in this context, we do need some way of indicating that the effect of God at this level, and so at all levels, is that of pattern shaping in its most general sense. I am encouraged in this kind of exploration by the recognition that the concept of the Logos, the Word, of God is usually taken to refer to God’s self-expression in the world and so to indicate God’s creative patterning of the world (see pp.158ff.).

The model is propounded to be consistent with the monist concept that all concrete particulars in the world-System are composed only of basic physical entities, and with the conviction that the world-System is causally closed. There are no dualistic, no vitalistic, no supernatural levels through which God might be supposed to exercising special divine activity. In this model, the proposed kind of interactions of God with the world-System would not, according to panentheism, be from ‘outside’ but from ‘inside’ it. The world-System is regarded as being ‘in God’. This seems to be a fruitful way of combining God’s ultimate otherness with God’s ability to interface holistically with the world-System.

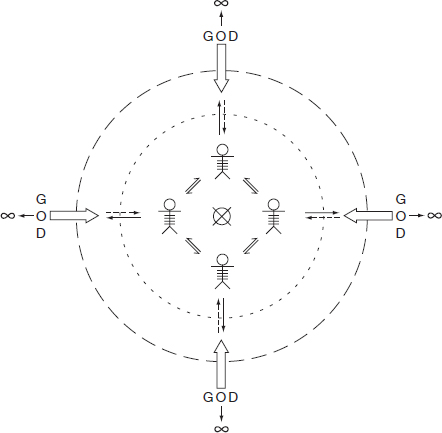

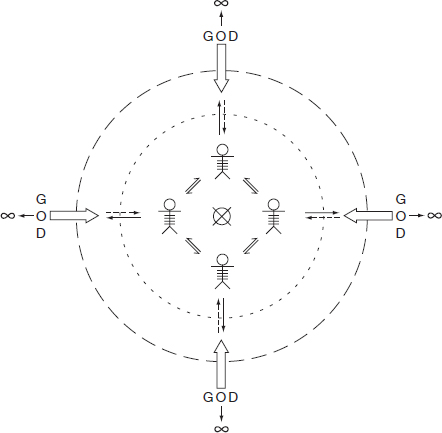

These panentheistic interrelations of God with the world-System, including humanity, I have attempted to represent in figure 1. This is a kind of Venn diagram and represents ontological relationships; the infinity sign represents not infinite space or time but the infinitely ‘more’ of God’s Being in comparison with everything else. The diagram has the limitation of being in two planes so that the ‘God’ label appears dualistically to be (ontologically) outside the world and although this conveys the truth that God is ‘more and other’ than the world, it cannot represent God’s omnipresence in and to the world. A vertical arrow has been placed at the centre of this circle to signal God’s immanent influence and activity within the world. It may also be noted that ‘God’ is denoted by the (imagined) infinite planar surface of the page on which the circle representing the world is printed. For, it is assumed, God is ‘more than’ the world, which is nevertheless ‘in’ God. The page underlies and supports the circle and its contents, just as God sustains everything in existence and is present to all. So the larger dashed circle, representing the ontological location of God’s interaction with all-that-is, really needs a many-dimensional convoluted surface not available on a two-dimensional surface. The figure is but a more mundane representation of Augustine’s vision of ‘the whole creation’ as if it were ‘some sponge, huge, but bounded ... filled with that unmeasurable sea’ of God, ‘environing and penetrating it though every way infinite ... everywhere and on every side’.9

Figure 1. Diagram representing spatially the ontological relation of, and the interactions between, God and the world (including humanity).

GOD |

God, represented by the whole surface of the page, imagined to extend to infinity (∞) in all directions |

|

the world, all-that-is: created and other than God, and including both humanity and systems of non-human entities, structures and processes |

|

the human world: excluding systems of non-human entities, structures and processes |

|

God’s interaction with and influence on the world and its events |

|

a similar arrow to the preceding one but perpendicular to the page: God’s influence and activity within the world |

|

effects of the non-human world on humanity |

|

human agency in the non-human world |

|

personal interactions, both individual and social, between human beings, including cultural and historical influences |

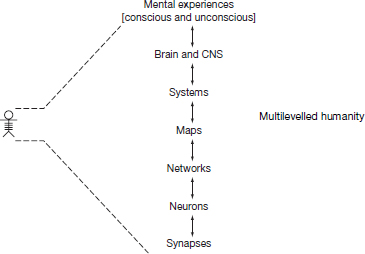

Apart from the top one, these are the levels of organisation of the human nervous system depicted in Patricia S. Churchland and T.J. Sejnowski, ‘Perspectives on Cognitive Neuroscience’, Science, 242, 1988, pp. 741–5.

In conclusion, this model of God’s interaction with the world as including a whole–part influence has proved, in my view, to be a promising path to take in our exploration from science towards an understanding of God’s special providence and has indeed been adopted by other thinkers, though often in combination with other, less warranted bottom-up proposals, such as those involving chaotic systems and/or quantum events.

I hope the model as described so far has a degree of plausibility in depending on an analogy only with complex natural systems in general and on the way whole–part influence operates in them. It is, however, clearly too impersonal to do justice to the personal character of many (but not all) of the profoundest human experiences of God. So there is little doubt that it needs to be rendered more cogent by the recognition that, among natural systems, the instance par excellence of whole–part influence in a complex system is that of personal agency. Indeed I could not avoid, above, speaking of God’s ‘intentions’ and implying that, like human persons, God had purposes to be implemented in the world. For if God is going to affect events and patterns of event in the world, then we cannot avoid attributing the personal predicates of intentions and purposes to God – inadequate and easily misunderstood as they are. So we have to say that though God is ineffable and ultimately unknowable, yet God is ‘at least personal’ and that personal language attributed to God is less misleading than saying nothing!

We can now legitimately turn to the exemplification of whole–part influence in the mind–brain–body relation (pp.59ff.) as a resource for modelling God’s interaction with the world. When we do so the ascendancy of the ‘personal’ as a category for explicating the wholeness of human agency comes to the fore and the traditional, indeed biblical, model of God as in some sense a personal agent in the world is rehabilitated. It is re-established here in a quite different metaphysical, non-dualist framework from that of much traditional theology but now consistently with the understanding of the world which the sciences provide. Accounts of religious experience are, of course, deeply suffused with the language of personal interaction with God and at this point our philosophical and theological explorations towards God begin to make contact with the common experiences of believers in God.

When we were using non-human systems in their whole–part relationships as a model for God’s relation to the world in special providence, we resorted to the idea of a flow of information as a helpful pointer to what might be conceived as crossing the ontological gap between God and the world-as-a-whole. But now as we turn to more personal categories to explicate this relation and interchange, it is natural to interpret the flow of information between God and the world, including humanity, in terms of the communication that occurs between persons – rather in the way that a flow of information in the technical engineering sense transmutes, say in a telephone call, in the human brain into ‘information’ in the ordinary sense of the word, so that communication occurs between persons. Thus, whatever else may be involved in God’s personal interaction with the world, communication must be involved and this raises the question of to whom God might be communicating. There would not have been such intense investigations into scientific perspectives on divine action if it had not been the case that humanity distinctively and, it appears, uniquely has regarded itself as the recipient of communication from God. But in what ways has the reception of communication from God been understood and experienced?