From September 1939 until April 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia escaped the war that was ravaging Europe. However, Germany and Italy exerted growing pressure on Yugoslavia, and on March 25, 1941, Prince Paul, the regent, agreed to join the Tripartite Pact signed by Germany, Italy, and Japan. Two days later, a military coup hostile to this pact ended the regency and brought young King Peter to power. Germany’s reaction was immediate and overwhelming: On April 6, 1941, German troops crossed the Yugoslav borders, and eleven days later, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia surrendered unconditionally. The first Yugoslav state was then dismantled, with Germany, Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Albania annexing large portions of it, while leaving a Serbian rump state under German protectorate. The Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska—NDH), covering Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, was proclaimed on April 10, 1941 (see Map IV). This dismantling of the Yugoslav state, by satisfying the irredentist demands of neighboring states and allowing the creation of a Croat nation-state, might suggest a belated triumph of the nation-state principle in the Yugoslav space. Yet such a triumph was largely an illusion. On the one hand, all the states involved were satellites of Germany or Italy, two countries that intended to dominate the “new European order.” These imperial aspirations were blatantly obvious with the NDH, whose territory was divided into two German and Italian occupation zones, and whose leaders were under direct tutelage of the occupying powers. On the other hand, in a Yugoslav space characterized by its diverse populations, any attempt to create homogenized nation-states could only lead to extreme violence and harsh resistance—as also illustrated by the NDH.

At the same time as the NDH was created, the Ustasha movement (formed in 1929) came to power. Returning from exile, the Ustasha leaders took control of the young Croatian state, and Ante Pavelić was appointed poglavnik (head of state). As a sign of allegiance to Nazi Germany, the new Ustasha power adopted racial laws based on the Nuremberg Laws and began the extermination of its Jewish and Roma populations. However, its treatment of the Muslim and Orthodox populations owed less to the demands of the Axis Powers than to its extremist interpretation of the Croat nationalist ideology formulated by Ante Starčević and Josip Frank in the nineteenth century. The Ustashas considered the estimated 900,000 Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina to be Muslim Croats, and reserved an eminent place for them in their nationalist rhetoric. For example, in April 1942, the newspaper Sarajevski novi list (“The New Sarajevo Journal”) wrote:

Map IV The Yugoslav space between 1941 and 1945.

The Muslim Croats also owe Dr Ante Starčević, the Father of the Homeland, infinite thanks, for Dr Starčević is the man who, in Europe, took the defense of the purest Croat blood, that of the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina… He emphasized that the Muslims are the purest Croats, for they have always been Croats, and during the Ottoman regime, they were able, as Muslims, to preserve their Croat consciousness more easily. Starčević viewed Muslims as the flower of Croat identity.1

While the new Ustasha state considered a rapid and widespread nationalization of Bosnian Muslims within a bi-confessional Croat nation, the case was different for Orthodox Serbs, who represented around 1,900,000 people, i.e. one-third of the population of the NDH. For the Ustashas, the Serbs were a foreign body within the Croat nation-state, to be eliminated through their conversion to Catholicism, their expulsion to Serbia, or their extermination, pure and simple. In summer 1941, Ustasha military formations committed several massacres in regions with a Serb majority, whereas widespread conversion campaigns were organized with the complicity of some Catholic priests. But the primary symbol of Ustasha violence remains the Jasenovac concentration camp, which opened in 1941 and where, according to Vladimir Žerjavić’s calculations, 45,000 to 50,000 Serbs, 13,000 Jews, 10,000 Roma, and 12,000 Croat or Muslim opposition members all perished.2 The Ustasha plans for a homogenous Croat nation-state thus led to extreme violence toward the non-Croat populations of the NDH.

The German and Italian occupying authorities disapproved of the Ustasha regime’s anti-Serb violence, since it contributed to the rapid deterioration of the military situation. Indeed, as early as 1941, the Serbs of the NDH responded to the Ustasha massacres by taking up arms and seeking refuge in zones not under the control of Croat authorities. This insurrection was largely spontaneous, but would soon be led by two resistance movements with diverging national and ideological objectives. The Chetnik movement (from četa, armed band), also called the Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland (Jugoslovenska vojska u otadžbini), was headed by Colonel Draža Mihailović and supervised by former Yugoslav Army officers. Politically, this movement aspired to restore the Kingdom of Yugoslavia under Serb domination, and to create a large Serb entity with the expulsion of non-Serb populations. Draža Mihailović himself, in his instructions to two Chetnik commanders, spoke of the “creation of a Great Yugoslavia, and within it, an ethnically pure Great Serbia,” and therefore planned for “purification of the state territory of all national minorities and foreign elements,” including the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Sandžak.3 On the ground, the Chetniks committed several massacres of Muslims during the early years of the war, notably in eastern Bosnia and the Sandžak. In this case as well, the war fueled the radicalization of nationalist ideologies, and the Chetnik plans for a Great Serb nation-state resulted in extreme violence toward non-Serb populations.

The Partisan movement arose alongside the Chetnik movement. Also called the People’s Liberation Army of Yugoslavia (Narodnooslobodilačka vojska Jugoslavije), the Partisan movement was led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) and headed by its Secretary General, Josip Broz—known as Tito. In keeping with the ideas defended by the KPJ since the 1930s, and in opposition to the acute nationalism of the Ustashas and the Chetniks, the Partisans extolled fraternity among all the peoples of the Yugoslav space. They intended to create a new Yugoslav state that would acknowledge the national specificity of each people. Thus, the Partisan movement viewed the plurinational character of the Yugoslav space positively, and intended to leverage this element in the struggle for people’s liberation. Admittedly, early in the war, ordinary Partisan units were generally regional and mononational, but the proletarian brigades—mobile and highly ideological elite units—included combatants of various nationalities.

In the early months of the war, the front lines generally followed the divisions between communities. The regular army and Ustasha formations of the NDH, made up of Catholic Croats, and Muslims, faced off against Chetnik and Partisan groups that were mainly Serb. At that period, Chetniks and Partisans fought side by side, and the two groups were sometimes hard to distinguish from each other. However, by late 1941, their divergent ideological and strategic orientations caused violent clashes in Serbia and eastern Bosnia. The Chetnik movement did not hesitate to appeal to the “anti-Turk” sentiments of the Serb population in order to destabilize the Partisans. Over the course of 1942, considerable political and military restructuring took place within the NDH. On the one hand, faced with the growing insurrection and pressure from the German and Italian authorities, the Ustasha regime pulled back on its anti-Serb policy. Generals Slavko and Eugen Kvaternik, deemed to be responsible for the 1941 massacres, were stripped of their duties, and a Croatian Orthodox Church was founded so that the Orthodox could integrate the Croat nation more easily. On the other hand, in an effort to protect Serb populations, the Chetnik movement made local agreements with Italian occupation forces, thus strengthening its presence in the southern portion of the NDH. Then, increasing its collaboration, it made similar agreements with the German forces and the Ustasha authorities. Weakened by the constant assaults by its adversaries and by the defection of many of its combatants, the Partisan movement was able to rebuild its forces in western Bosnia and to assert itself gradually as the main Yugoslav resistance movement. Its rising influence was symbolized by the first session of the Anti-Fascist Council for People’s Liberation of Yugoslavia (Antifašističko vijeće narodnog oslobođenja Jugoslavije—AVNOJ), held on November 26 and 27, 1942 in Bihać. At that point, the main fault lines had ceased to be ethnic: the Partisan movement gradually expanded to recruit Muslims and Croats, whereas the foreign occupation forces, Ustasha formations, and Chetnik groups cooperated ever more closely in their fight against the Partisans. The national projects defended by the Ustashas and the Chetniks were lost in the twists and turns of a particularly brutal, complex civil war, leaving room for circumstantial alliances that varied over time and space.

When Italy surrendered on September 8, 1943, the Chetnik movement lost its main political and military support. Conversely, the Partisan movement continued to gain strength. On November 29, 1943, during the second session of the AVNOJ in Jajce, the Partisans proclaimed a new Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (Demokratska federativna Jugoslavija—DFJ). The Chetnik movement, meanwhile, made a belated effort to broaden its base beyond just the Serb community, and encouraged the formation of Muslim units, albeit fairly unsuccessfully. These projects were in vain, and they arrived after several years of anti-Muslim violence, as the Chetnik movement was in decline. In August 1944, King Peter II, in exile in London, removed Mihailović from his position as Chief of the General Staff of the Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland, thus isolating him even further.

Over the last two years of the war, the Partisan movement’s supremacy became irreversible, and it seemed to be the only movement capable of ensuring the safety and peaceful coexistence of the Yugoslav peoples. The main concern of its communist leaders was, at that time, to obtain international recognition for the new Yugoslav state, and to crush their adversaries definitively. In November 1944, Tito made an agreement with Ivan Šubašić, head of the royal government-in-exile, to create a provisional government presided by Tito himself. In March 1945, King Peter II accepted the appointment of a Regency Council until the structure of the new Yugoslav state could be determined. In parallel, the People’s Liberation Army of Yugoslavia and the Red Army steadily pushed back the German forces and their local allies toward the northwest of the Yugoslav space. Belgrade was liberated on October 20, 1944, Sarajevo on April 6, 1945 and Zagreb on May 9, 1945. In the following weeks, British troops repelled members of collaborationist units who attempted to find refuge in Austria. Several tens of thousands of these troops were then killed by the Partisans in a series of massacres and forced marches known as the “Bleiburg massacre.” Thus, the war ended in the Yugoslav space just as it had begun, with a wave of extreme violence, whose fault lines were no more ethnic but ideological.

In barely four years, the Second World War had left more than a million dead in the Yugoslav space, i.e. 6 percent of the total Yugoslav population, including 300,000 to 400,000 dead in Bosnia-Herzegovina alone, i.e. 10–13 percent of the total Bosnian population. The particular intensity of the massacres and fighting in Bosnia-Herzegovina explains why, within Yugoslavia, the Bosnian Muslim community was, after the Jewish and Roma communities, the most affected by the war. But in Bosnia-Herzegovina itself, Serb casualties were much higher than Muslim ones, reflecting the gravity of the Ustasha crimes and the Serbs’ early involvement in the Partisan movement.4 In four years, the war in the Yugoslav space was marked both by an onslaught of extreme violence and by a series of shifting alliances, during which ethnic divisions gradually diminished in favor of ideological ones. In the throes of war, the plans for homogeneous nation-states defended by the Ustashas and the Chetniks collapsed under the weight of their own contradictions and violence. A new plurinational Yugoslav state emerged from their ruins, modeled after the Soviet Union and led by a victorious communist party. We must now look at how the Muslim political and religious elites positioned themselves during this war that jeopardized the very existence of their community.

In the weeks that followed the proclamation of the NDH, the Muslim political and religious elites of Bosnia-Herzegovina gave their allegiance to the new Ustasha state. However, we must distinguish between those who rallied the NDH following a long period of pro-Croat activism, and those for whom the NDH merely represented a new central power succeeding the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The former group included the politicians belonging to the Muslim Organization (Muslimanska organizacija—MO) since 1935, some of whom were given important positions in the new regime: thus, Adem-aga Mešić became doglavnik (deputy head of state), alongside Ante Pavelić, and Hakija Hadžić was appointed as Pavelić’s representative in Sarajevo. The same enthusiasm for the young Ustasha state could be found among the pro-Croat intellectuals associated with the magazine Novi behar or with the cultural society Narodna uzdanica.5 The leaders of the former JMO were apparently more reluctant to support the new regime, and Džafer Kulenović did not accept the position of vice prime minister until November 1941. Lastly, the ‘ulama’ replicated their strategy of trading their support for the central power in exchange for minimal security and religious autonomy. Thus, speaking in the great mosque of Sarajevo on May 11, 1941, the Reis-ul-ulema Fehim Spaho declared:

[W]hereas numerous other countries have been the theatre of terrible scenes of warfare, we have reached, with a limited number of victims and after a very brief period, a situation where we can say: We have our state. The Independent State of Croatia has been born and has begun to live. We Muslims have greeted it with all our hearts, bearing in mind that we are entering it as citizens with equal rights and strongly believing that no injustice will be committed against any Muslim.6

Three months later, in the name of the association el-Hidaje, Mehmed Handžić and Kasim Dobrača were part of a Muslim delegation that met with Ante Pavelić to pledge allegiance, all the while insisting on their wish for a revision to the Constitution of the Islamic Religious Community. On a local level, other Muslims rallied the NDH in a similar way, and although few Muslims were present in the upper echelons of the state apparatus, they often held local responsibilities in regions with Muslim populations, thus participating in the Ustasha violence against Serbs and Jews. Moreover, the Muslim elites’ support for the NDH went beyond its borders, as several petitions from Muslim notables in the Sandžak called for their region to be attached to the Ustasha state.

To understand the reasons why the Muslim political and religious elites rallied the NDH on such a wide scale, we must remember that they had been marginalized during the interwar period, then sidelined completely with the Cvetković–Maček Agreement in August 1939. Compared with the partition of the territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina and the subsequent political negation of the Muslim community, the integration of Bosnia-Herzegovina into the NDH and the Muslims’ promotion to the rank of “flower of the Croat nation” may have seemed like an attractive alternative. Although in some ways the Muslim elites’ support of the NDH was an extension of the political strategies developed since the Austro-Hungarian period, it also highlighted how these strategies had become obsolete in a radically new context. The NDH was neither an empire nor a plurinational state, but a racist and dictatorial nation-state determined to use violence to achieve its political ideal. As a result, the political rationales driving the NDH were, at best, foreign to the Muslim elites, and at worst, completely incompatible with their conception of the world. Admittedly, the NDH’s policy of nationalizing the Bosnian Muslims met with no open opposition; intellectuals, politicians, and ‘ulama’ agreed, more or less enthusiastically, to consider themselves Croats of Islamic faith. But this nationalization was all the more superficial as the Ustasha state soon lost its authority over large stretches of its territory. In reality, Bosnian Muslims continued to consider themselves chiefly in religious terms, and even pro-Croat intellectuals expressed a strong sentiment of belonging to a distinct and threatened Muslim community. Thus, in the newspaper Osvit (“Dawn”), published by young intellectuals close to Hakija Hadžić and the association el-Hidaje, the son of Džemaludin Čaušević, Halid, wrote:

[W]e too, as an inseparable part of our heroic [Croat] nation, have the right to live and exist in this corner of Europe. We are not an a-national element and we consider it the highest offence when our nationality is demonstrated in a so-called scientific way. If nationalism lies in the awareness of solidarity and a spiritual and moral unity (by spiritual unity, we do not mean religious unity, as nationality and religion are totally different concepts), in pure and preserved national language and customs, in fanatical love for the homeland, then we Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina are nationalists in the full sense of the word… Now we must both defend our skins and take giant steps forward if we do not want time to get ahead of us. And we cannot permit it, because without us, our state lacks Herceg-Bosna7 and without us, there is no Islam in Europe.8

The Muslim elites, however, were not unanimous in their support to the NDH. On the one hand, these elites were fairly disoriented and afflicted by certain long-term conflicts. The question of revising the Constitution of the Islamic Religious Community, in particular, continued to pit the former JMO’s leaders against the revivalist ‘ulama’ of el-Hidaje. The former sought to maintain their control of the religious institutions, while the latter were determined to restore the ‘ilmiyya’s prerogatives. Careful not to turn the Muslim political elites against them, the Ustasha authorities continued to waffle on this matter, but this caused growing hostility from the revivalist ‘ulama’. On the other hand, the rhetoric of the Muslims as the “flower of the Croat nation” did not stop the Ustasha state from actually favoring Catholic Croats. Throughout the war, the Muslim community’s representatives complained about the privileged status enjoyed by the Catholic Church and the Muslims’ underrepresentation in the state apparatus. However, the first major confrontation between the Ustashas and a portion of the Muslim elites came in 1941 due to the extreme violence of the NDH. Rapidly, the nationalist and racist violence of the Ustashas came into contradiction with the communitarian rationale favored by the Muslim elites. Thus, the Islamic Religious Community defended Muslim Roma, was shocked that Jewish families were still persecuted after converting to Islam, and was indignant when the Ustasha authorities prevented some Serb villages from converting to Islam rather than Catholicism. At the same time, the Ustasha anti-Serb violence triggered a wave of Chetnik reprisals against the Muslim community, thus indirectly threatening its physical security. As a result, Ustasha violence weakened the Bosnian Muslim elites’ ties of allegiance to the NDH. This was the background to the resolutions adopted by Muslim notables in various Bosnian towns between August and December 1941.

The first such resolution was adopted on August 14, 1941 by the association el-Hidaje, which continued its politicization process that had begun in the 1930s. In a dictatorship in which the Muslim political elites were either integrated into the Ustasha state apparatus, or likely to come under pressure from the Ustashas, this religious association claimed to speak for the Muslim community. In its resolution, it first mentioned the Muslim victims of Chetnik massacres, before also condemning “all Muslim individuals who may have purposely caused any disorder or committed any violence of any sort,” and called on the Croat authorities to “restore, as quickly as possible, law and order in all the regions by preventing any spontaneous actions in order to avoid innocent people suffering.” The association el-Hidaje thus implicitly condemned anti-Serb violence and called for the rule of law to be re-established. Yet it also reaffirmed its allegiance to the Ustasha state, noting its commitment to religious freedom, insisting on the equal rights shared by Catholic Croats and Muslims as the basis for “fraternal cooperation by all members of the Croat nation in building our young state,” and even asked for the Sandžak to be attached to the NDH.9

In the following months, as violence spread throughout Bosnia-Herzegovina, Muslim notables adopted other resolutions in Prijedor (September 23), Sarajevo (October 12), Mostar (October 21), Bijeljina (December 2), and Tuzla (December 11). These resolutions all emphasized the dramatic situation faced by Bosnian Muslims, with the Sarajevo resolution even asserting that “in their history, the Muslims of these regions have not known a more difficult time.”10 In more or less vigorous terms, they condemned the massacres against the Serb population, calling for the perpetrators to be brought to justice and the rule of law to be restored. Sometimes, the values of Islam were mentioned to denounce Ustasha violence. For example, the Mostar resolution stated:

[A]ny true Muslim, ennobled by the high precepts of Islam, condemns such crimes, from whichever side they are committed, for he knows that the Islamic religion considers the murder and torture of innocents to be the gravest of sins, alongside the theft of others’ goods and forced conversion. Only a handful of individuals purporting to be Muslims has violated the high precepts of Islam, and punishment from God and from men shall inevitably reach them.11

The contradiction between the NDH’s nationalist, racist rationales and the Muslim notables’ religious perspective is clearly apparent here. However, the signatories were still hesitant concerning Muslim participation in Ustasha crimes, and while certain resolutions admitted that some Muslims had taken part in massacres, others accused Ustasha militiamen of wearing the fez in order to trigger a cycle of Serb retaliation against Muslims or to push the Serbs into the arms of the Catholic Church.

The 1941 Muslim resolutions were a courageous act condemning the Ustasha state’s violence against Serbs, at the same time expressing a feeling of insecurity and powerlessness as war broke out, and a desperate appeal to restore a protective state. This is why these resolutions never led to a complete break with the Ustasha state or the occupying powers. Thus, the fate of the Jews was largely ignored in order to avoid any conflict with the German authorities. Likewise, the massacres and abuses were often attributed to local authorities or rogue militiamen, with the central power then being asked to restore order and security. Lastly, the resolutions sometimes mentioned the tolerance that the Muslims showed in the Ottoman period, but they did not call for autonomy for Bosnia-Herzegovina or include any proto-nationalist message. The signatories of the 1941 resolutions were thus carrying out a strong moral action in a perilous context, but they did not actually break with the strategies of allegiance to the center that had traditionally characterized the Muslim elites. Moreover, they deployed methods that had no doubt proven effective during the Ottoman or Austro-Hungarian periods, but held no sway with a dictatorship during a total war. This explains why, as the war progressed, the signatories did not always avoid the moral compromises and strategic impasses into which some of the Muslim political and religious elites strayed.

The 1941 Muslim resolutions showed that, in a context of war and dictatorship, a portion of the Muslim elites mobilized through informal networks of notables and associations such as el-Hidaje. The Islamic Religious Community as such could not play this political proxy role, because after the death of Fehim Spaho in February 1942, it was led by a naib-ul-reis (i.e. a vice-reis) with no great authority and by a weakened, divided ulema-medžlis. Whereas a portion of the Muslim political and religious elites remained loyal to the Ustasha state until its collapse, the Muslim political and religious leaders that wanted to distance themselves from the NDH were slow to organize. It was not until August 26, 1942, following additional Chetnik massacres in eastern Bosnia, that 300 Muslim notables met in Sarajevo in the offices of the Muslim charity Merhamet (“Mercy”), under the auspices of the naib-ul-reis Salih Bašić. The debates were led by Muhamed Pandža, a member of the ulema-medžlis, vice president of Merhamet and signatory of the 1941 Muslim resolution of Sarajevo. The assembly set the goals of organizing aid for Muslim refugees from eastern Bosnia, finding weapons to defend the Muslim population, and alerting the Muslim world to the fate of the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina. It therefore appointed a People’s Salvation Committee (Odbor narodnog spasa) comprising forty-eight members and chaired by Mehmed Handžić, the president of the association el-Hidaje. This committee included other ‘ulama’ such as Muhamed Pandža and Kasim Dobrača, a member of the board of el-Hidaje, as well as former JMO leaders, such as Uzeir-aga Hadžihasanović, a former close collaborator of Mehmed Spaho, and Mustafa Softić, Hadžihasanović’s son-in-law and the mayor of Sarajevo.

The creation of the People’s Salvation Committee coincided with a renewed demand for the autonomy of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Moreover, certain committee members, notably Mehmed Handžić, had belonged to the short-lived Movement for the Autonomy of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1939. However, British historian Marko Hoare goes too far when he places this Muslim autonomist movement on the same level as the Partisan movement, describing them as “two autochthonous movements that resisted Bosnia’s incorporation in the NDH and that sought its restauration as an autonomous entity in some form.”12 On the one hand, the Muslim autonomists did not break completely with the NDH authorities. On the other, they merely formed an informal coalition of notables, whereas the Partisans constituted a genuine armed resistance movement. At least until 1943, most Bosnian Muslims involved in the war were in the various armed formations of the NDH, ranging from the regular Croatian army to various Ustasha units, such as the infamous Crna legija (“Black Legion”). In late 1941, several militias made up solely of Muslim combatants appeared. These were generally local units, although some of them had several thousand members, such as the Home Guard Volunteer Regiment (Domobranska dobrovoljačka pukovnija—DOMDO) founded by Muhamed Hadžiefendić in the Tuzla region.

Although these Muslim militias enjoyed broad autonomy on the ground, they still had ties with, and were largely armed by, the Ustasha authorities and occupying troops. Thus, these militias were a sign of the Muslim population’s quest for security, which the NDH was unable to provide, but they did not convey political claims. Their ties with the People’s Salvation Committee were either inexistent or limited to a few informal contacts. Lacking their own military force, the Muslim notables in the People’s Salvation Committee had very limited leeway for action. Furthermore, to achieve their goals, they were not counting on Muslim political mobilization, but rather on protection from what they regarded as the new imperial power in Europe: the Third Reich.

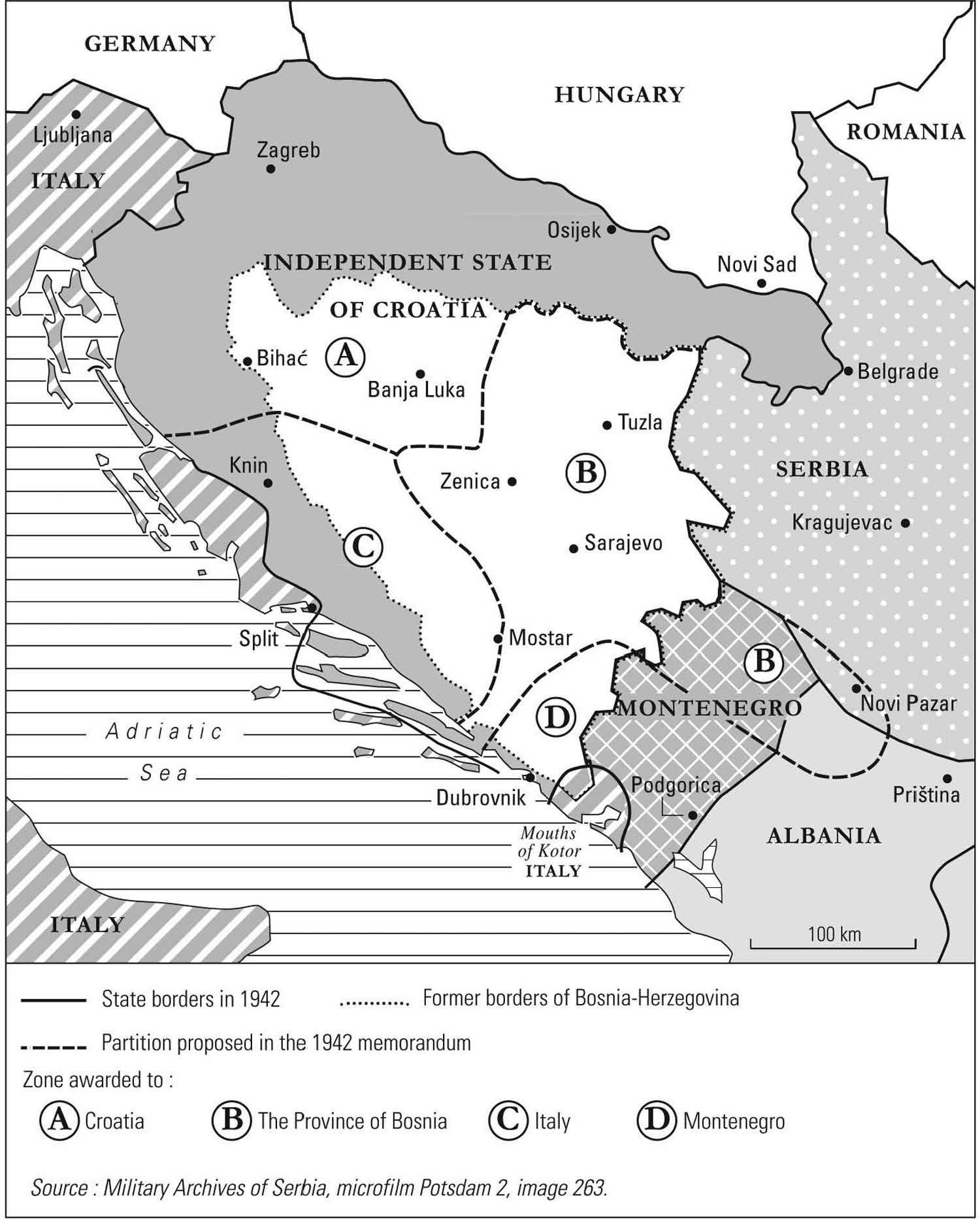

Indeed, while a movement for the autonomy of Bosnia-Herzegovina was discreetly being revived with the People’s Salvation Committee, a demand for imperial protection was being addressed to the Axis Powers. In October 1942, a delegation of the ‘ulama’ and Muslim notables from Mostar visited Rome to seek Italian support for forming Muslim militias and to meet with the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Amin al-Husayni, who was attempting to mobilize the Muslim world in favor of the Axis Powers. Meanwhile, Muhamed Pandža was asking the commander of the German forces in Croatia to provide weapons for Muslim militias. However, the Italian authorities gave priority to their alliances with the Chetnik movement, and the German military authorities suggested that Pandža should contact the Ustasha authorities. In November, a memorandum was written and addressed to Adolf Hitler, signed by a “People’s Committee” (narodni odbor). This document expressed both a demand for autonomy for Bosnia-Herzegovina and an appeal to the Third Reich as an imperial power. Indeed, the authors insisted on their allegiance to Nazi Germany. For example, they wrote that no other people in Europe had shown such great loyalty to the “new European order,” while they denounced the Ustasha state for allowing many Jews to convert to Catholicism, and proposed that Bosnian Muslims could be “the bridge and the tie between the West and the East, with its 300 million Muslims.”13 Claiming that only a few intellectuals had gone astray and declared themselves to be Serbs or Croats, the memorandum declared that Bosnia-Herzegovina had more historical reasons to be autonomous than Serbia or Croatia. Thus, it proposed transforming the region into a “Province of Bosnia” (župa Bosna) under the protection of the Third Reich. In this autonomous province, the Ustasha movement would have been banned and replaced by a Bosnian National Socialist Party, and a “Bosnian guard” (bosanska straža) would have been formed from Hadžiefendić’s militiamen and all the Muslim soldiers and officers of the NDH, apart from those fighting on the Eastern Front. Lastly, this memorandum proposed that Bosnia-Herzegovina should be divided into a territory B, corresponding to the Province of Bosnia, and territories A, C, and D, attached to Croatia, Italy, and Montenegro, respectively (see Map V). So that the Bosniaks would be the absolute majority in the Province of Bosnia, a suggestion was made to carry out population transfers. According to the memorandum’s authors, the Province of Bosnia would have a population of 750,000 Bosniaks, 600,000 Serbs, and 300,000 Croats before any population transfer, versus 925,000 Bosniaks, 500,000 Serbs, and 225,000 Croats after the proposed transfers.

The November 1942 memorandum—which German sources attribute to Uzeir-aga Hadžihasanović, Mustafa Softić, and Suljaga Salihagić—did not necessarily reflect the views of all members of the People’s Salvation Committee. It nevertheless showed how, in a context of bloody confrontation between Serb and Croat nationalisms, the political and religious leaders of the Muslim community were forced to reason in nation-state terms. This memorandum was de facto a “first draft” of a Muslim nation-state project, and it reveals the inevitable contradictions of such a project. On the one hand, the proposed creation of a Province of Bosnia showed the difficult balancing act between preserving Bosnia-Herzegovina and creating a national state for Bosnian Muslims; this difficulty would reappear fifty years later, with the violent breakup of Yugoslavia. Taking account of the balance of power at the time, both in the Yugoslav space and in Europe, the memorandum’s authors renounced the territorial integrity of Bosnia-Herzegovina and reluctantly rallied the idea of more or less homogeneous national entities, formed through exchanges of territory and populations. On the other hand, to escape the NDH’s domination, the authors combined their demand for autonomy for Bosnia-Herzegovina with a search for imperial protection, offering their political and ideological allegiance to the Third Reich. Thus, in this memorandum, a barely sketched national project was immediately reincorporated into an imperial framework. From this point of view, the demand for autonomy in the November 1942 memorandum was perhaps more similar to the Muslim political claims during the Austro-Hungarian period than to the Movement for the Autonomy of Bosnia-Herzegovina of the late 1930s. Here again, the memorandum authors had to take into account some priorities and balances of power. However, these largely pragmatic calculations were also fueled by a misplaced nostalgia for the Austro-Hungarian Empire that the Third Reich instrumentalized by presenting itself as its legitimate heir. Motivated by a desire to protect the Muslim community from Chetnik violence, these calculations led their authors to collaborate with the German occupiers and eventually condemned them to political irrelevance.

Map V Partition of Bosnia-Herzegovina proposed in the 1942 memorandum.

For several months, the German authorities hesitated as to the appropriate attitude toward the autonomist milieus and the credit to give to the November 1942 memorandum. However, the signs of allegiance from Muslim autonomists attracted the interest of certain SS leaders, including Heinrich Himmler. In February 1943, the decision was made to create a Waffen SS division with Muslim troops. The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husayni, living in Berlin since November 1942, was involved in this project. In April 1943, al-Husayni went to Sarajevo to promote the idea among the leaders of the Bosnian Muslim community. For the SS leaders, the creation of this Muslim division would have freed up German troops for the Eastern Front, while also serving as an instrument of propaganda for the Muslim world. Al-Husayni also saw the advantage that he could harness for his own pan-Islamic ambitions, and he positioned himself as the middleman between the SS leaders and Bosnian Muslim notables. Therefore, he took responsibility for presenting the SS leaders with some Bosnian demands, notably not to recruit members of Hadžiefendić’s militia for the SS division and to keep the division in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Furthermore, he negotiated an agreement about the place of Islam in the Waffen SS. This agreement stipulated that “there are no plans to find a synthesis between Islam and National Socialism, or to impose National Socialism on Muslims.” According to this agreement, “National Socialism is conveyed to Muslims as a German national ideology, and Islam as an Arab national ideology, with emphasis on their common enemies,” namely Judaism, Anglo-Americanism, Communism, Free Masonry, and Catholicism. The agreement concluded by expressing a wish that, “with the establishment of a Muslim SS division, for the first time a tie can be formed between Islam and National Socialism on a frank and sincere basis, as this division will be bound to the North by race and blood, but to the Orient by philosophy and spirit.”14

Recruitment for the Muslim SS division, officially called the 13th SS Division but better known as the Handžar division (“Dagger division”), quickly created tension between the Waffen SS and the Ustasha authorities, who demanded that recruitment should take place under their control and should be opened to Catholic Croats. As there were not enough volunteers, the Waffen SS forcibly incorporated Hadžiefendić’s militia into it and forced the NDH to transfer thousands of Muslim soldiers from certain regular or Ustasha units. The political and religious leaders linked to the autonomist milieus apparently viewed the creation of the 13th SS Division sympathetically, without being outspoken in their support. This is either because they feared the reactions of the Ustasha authorities, or because the German defeats of El Alamein and Stalingrad had undermined their confidence in the Third Reich. Only Muhamed Pandža played an active role in recruiting volunteers, especially the imams in charge of the troops’ religious and ideological supervision. Among these imams was Husein Đozo, an ‘alim trained at al-Azhar University, close to the el-Hidaje association and a signatory of the 1941 Muslim resolution of Sarajevo. In 1944, after being given responsibility for training the young imams of the 13th SS Division, Đozo wrote in the division’s newspaper:

Communism, capitalism and Judaism are side by side [fighting] against the European continent. After the terrible suffering endured in our Croat fatherland, and more particularly in Bosnia-Herzegovina, we have learnt what it means when the enemies of Europe govern. This must not come to pass, and this is why the best sons of Bosnia are serving in the SS.15

Although some imams appeared to adhere to the idea of a convergence between Islam and National Socialism, most of the division’s troops were probably unaware of this ideological dimension to the Muslim SS division project. Indeed, after it was formed, the 13th SS Division did not live up to expectations. The Germans quickly realized that this division was unreliable on an ideological level and not very effective militarily. Sent to France for training, the division was hurriedly recalled to Germany after a battalion mutinied in September 1943. Back in Bosnia-Herzegovina in March 1944, it took part in several operations against Partisans in the Tuzla region and carried out several large massacres, collaborating with the local Muslim militias and Chetnik groups. It attempted to impose an SS political and military order despite the protests of the Ustasha authorities. However, the Partisan movement quickly regained the upper hand, and the 13th SS Division proved increasingly less combative and saw its troop numbers shrink due to desertions until it was transferred to Hungary in late 1944. At that time, it had already ceased to be a major military force. Within the autonomist milieus, the disillusionment was also considerable. The Third Reich took advantage of the Muslim community’s quest for security to create a Muslim SS division, but continued to favor its alliance with the NDH; thus, it took no action on the demands for the autonomy of Bosnia-Herzegovina. From this standpoint, Marko Hoare’s description of the 13th SS Division as “the flagship Muslim autonomist force” is misleading.16 In reality, this division absorbed Hadžiefendić’s militia and thousands of other Muslim soldiers, before being sent away from Bosnia-Herzegovina for several months. As a consequence, the Muslim community was even weaker as it faced the Chetnik movement. Lastly, after the division returned to Bosnia-Herzegovina, it followed the priorities of the German military command, joining with the Chetniks to fight the Partisans.

This disillusionment with regard to the 13th SS Division partially explains why the autonomist milieus were so disoriented and despondent toward the end of the war. In October 1943, Muhamed Pandža, the most enthusiastic proponent of the 13th SS Division, broke with this project and attempted to set up a Muslim Liberation Movement (Muslimanski oslobodilački pokret), defending plans for “an autonomous Bosnia in which everyone will have the same rights regardless of religion—Muslims, Orthodox and Catholics.”17 Yet this movement only brought together a few hundred combatants and it quickly disbanded. Pandža was captured by the Partisans, then by the Germans, and was imprisoned for the rest of the war. In the meantime, two of the main figures of the autonomist milieus died: Uzeir-aga Hadžihasanović in September 1943 and Mehmed Handžić in July 1944. The Muslim autonomists were reduced to gathering information about Chetnik massacres, adopting additional resolutions calling for peaceful coexistence with the Serb and Croat communities, while avoiding taking a political stance. They also wrote additional memorandums—this time, addressed to the Allies. However, there is no certainty that these memorandums ever reached their intended recipients, and they would only be discovered several decades later in the private archives or political files of some Muslim figures.

During the Second World War, the association el-Hidaje played a central role in the Muslim community’s attempts to organize politically, as shown by the first Muslim resolution adopted by el-Hidaje in August 1941 or by Mehmed Handžić’s appointment as president of the People’s Salvation Committee the following year. At the same time, the association provided the institutional framework for the development of a youth movement of pan-Islamist inspiration, the Young Muslims (Mladi Muslimani). This movement was founded in March 1941, just a few weeks before the war began, by high school and university students eager to rediscover their Islamic faith. Its name was borrowed from Egypt’s Young Muslims (al-Shubban al-muslimun), a youth organization with ties to the Muslim Brotherhood. Over the following months, the Young Muslims grew closer to el-Hidaje and organized their activities under its patronage, as a way to get around the prohibition of all youth organizations other than the Ustasha Youth. Lastly, in May 1943, the Young Muslims officially became the youth organization of el-Hidaje, led by Kasim Dobrača, a young ‘alim trained in Cairo at al-Azhar University. In November 1943, he was replaced by Mustafa Busuladžić, another young ‘alim who had studied in Rome.

In the meantime, the Young Muslim movement, which had initially been limited to a few high schools in Sarajevo and the University of Zagreb, set up a network of activists in around fifteen Bosnian towns. But what exactly were the social structure, the political ideology and the activities of this youth movement, especially in a specific context of war?

Most members of the Young Muslims came from families of urban notables, and thus were personally affected by the marginalization and disorientation of the traditional Muslim elites. Attending high schools in Bosnia-Herzegovina or the University of Zagreb, they were also directly confronted with the secularization of social mores and the rise of new ideologies like communism and fascism. It is unsurprising that these young believers were suffering from a deep identity and moral crisis. For example, in an article titled, “The Problem of our Youth,” medical student Esad Karađozović wrote that Muslim young people were in a desperate situation, distinguishing between three groups:

[O]ne group that has cast itself into the whirlwind of politics and contemporary ideologies, then a group of young snobs, socialites, gigolos, Don Juans and idlers, and lastly, an ignored and disrespected group of young people who are neither politicians nor show-offs, but who live withdrawn into themselves and their own world, far from the daily agitation of life, waiting, hoping and looking for their place without knowing what it is.18

Karađozović attributed the responsibility for this situation to the Muslim intellectuals, who had denied their religious traditions and betrayed their community by marrying non-Muslim women or by emancipating their Muslim wives. Then he extended this criticism to an entire generation of fathers who had given up on any ideal and merely eked out a living without standing up for themselves:

They all lower their heads like gentle lambs and no one dares to raise his head and look heroically towards the heavens, to accept the struggle for life and to create ideals to fight for, and to become a man, a Gentleman, a Muslim.19

Thus, Karađozović rejected the traditional Muslim elites’ loyalism and introversion, instead promoting a new proud and combative Muslim personality. For the Young Muslims, the identity and moral crisis affecting the Muslim community could be overcome if it returned to Islam, reaffirmed its Muslim identity and encouraged the re-Islamization of individual selves and society at large. And in fact, during the war, the bulk of the Young Muslims’ activities consisted of publishing religious articles in the magazine el-Hidaje, organizing readings of the Qur’an and lectures on different religious topics, and celebrating mevluds (ceremonies in honor of the Prophet).

The Islam that the Young Muslims wanted to promote was not very well defined, and their sources of inspiration varied widely, from the reformist Osman Nuri Hadžić to the revivalist Shakib Arslan, and even included Western writers, such as Oswald Spengler and Alexis Carrel. However, their overt aim of returning to the Islam of the Qur’an and the Sunna (traditions of the Prophet) and responding to secularization with a re-Islamization of social mores meant that they were close to the revivalism of the association el-Hidaje. Although in principle the Young Muslims rejected not only the secularism of the intellectuals, but also the mysticism of the Sufi sheikhs and the conservatism of the ‘ulama’, they were actually drawn to the activism of young revivalist ‘ulama’ such as Handžić, Dobrača, or Busuladžić. In an article that reads like a political program, Tarik Muftić, another medical student, wrote: “There is truthfully an enormous difference between what we mean today by ‘Islam’ and true Islam.” Then, he denounced the “Islam of compromise” (kompromisni islam) created first by the incorporation of Persian mysticism and Turkish folk religion into religious practice, and since 1878, by the reduction of Islam to a mere religious confession. Muftić, therefore, stated: “reawakening, renewal and reform are truly necessary—not reform of Islam, but reform and reawakening of the Muslims themselves.”20 He rejected the reformist authors who considered Europe and European thinking to be a model, supporting instead a return to an original Islam in which “everything is planned for and specified.”21 For Muftić, Islam was not simply a religion, whether traditional or reformed; instead, it was a total, unsurpassable social project—a political project carried by:

pan-Islamism—a movement whose goal is to reawaken the Islamic colossus from its secular slumber, and to create a great Islamic state of more than 400 million inhabitants belonging to the most diverse races and peoples—but all brothers.22

In Muftić’s view, there could be no doubt: “the greatest revolution in the history of humanity is the Islamic revolution”, with Islam being “the most perfect universal ideology.”23 In writing so, Muftić pushed the movement to politicize Islam, which the association el-Hidaje had begun in the 1930s, to its final conclusions.

However, the Young Muslims’ interest in political pan-Islamism was the factor that most set them apart from the ‘ulama’ of el-Hidaje, who remained focused on the fate of the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina. This political pan-Islamism resulted from a politicization of Islam following contact with fascist and communist ideologies. Faced with the racialized nationalism of the Ustashas and the new Yugoslav fraternity of the Partisans, the Young Muslims backed the solidarity of the Umma (the community of believers). Yet contrary to what the Young Muslims’ supporters have asserted, this does not mean that the movement was both anti-fascist and anti-communist—in a word, anti-totalitarian. In his writings from the Second World War, Mustafa Busuladžić—one of the ‘ulama’ who influenced the Young Muslims—clearly took a stance in favor of the Axis Powers. For example, in August 1943, he deemed that:

living in this corner of Europe, i.e. at the frontier between East and West, and having the dynamism of the West and the spiritual values of the East, we are predestined to connect Europe, and especially Italy and Germany, with the Islamic world, to the benefit of our country and the Muslim religious community.24

This analysis is relatively close to the one developed at the same period by Amin al-Husayni and the portion of the Muslim elites that split with the NDH to turn toward the Third Reich, even though Busuladžić appears to have remained loyal to the Ustasha state. As for political pan-Islamism, it offered the Young Muslims a political utopia, an imaginary empire in contrast with the isolation and turmoil afflicting the Bosnian Muslims, at a time when their very existence was threatened by the extreme violence of the Chetniks and the Ustashas. By seeking refuge in this pan-Islamist utopia, the Young Muslims avoided taking a stance on the actual situation in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and thus attempted to escape from the hesitations and contradictions of their community.

Given its status as the youth organization of el-Hidaje and the young age of most of its members, the Young Muslim movement was not forced to take a stance on the war that was raging. In fact, the Mladi Muslimani supplement printed in the el-Hidaje magazine never spoke of the war. At the very most, the Young Muslim movement took part in aiding Muslim refugees from eastern Bosnia, alongside the charity organization Merhamet. However, some Young Muslims became more politically involved on an individual basis, participating in the diffusion of the 1941 Muslim resolutions or attending the reception hosted by Amin al-Husayni in April 1943. Those responding to the mufti’s invitation included a Young Muslim named Alija Izetbegović, who would become the first president of the independent Bosnia-Herzegovina forty-eight years later.25 At least three Young Muslims became imams in the 13th SS Division.26 During this period, in Osvit, Mustafa Busuladžić wrote:

The gravity of the era in which we find ourselves does not allow for any hesitation or indecisiveness, but imposes unity and solidarity… In these days of jihad, we must all be combatants, defending our faith and our lives using all the means that our enemy uses. By fighting for our very existence, we must have in mind the words of a thinker who says that a man among wolves must not be a lamb.27

However, at the end of the war, the Young Muslims of fighting age were dispersed across various military formations. Indeed, they were enrolled in the regular Croatian Army, Muslim militias, the 13th SS Division, Pandža’s Muslim Liberation Movement, and in the Partisan movement, which mobilized increasing numbers of young Bosnian men as it gained ground. From this standpoint, the fate of the Young Muslims reflected that of Muslim Bosnians in general: the Young Muslim movement reacted to, but did not overcome, the Muslim community’s powerlessness. And, while the Young Muslims were dreaming of an Islamic state of 400 million inhabitants, a more modest imperial entity was taking shape in the Yugoslav space, gradually appearing to be the sole salvation for the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Of all the protagonists of the Second World War in the Yugoslav space, the Partisans were the only ones to tirelessly defend the idea of a new Yugoslav state and thus to advocate renewed coexistence between the Serbs, Croats, and Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Beginning in June 1941, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia’s (KPJ) provincial committee for Bosnia-Herzegovina appealed to the three main Bosnian communities to halt their fighting and massacres. However, in the first two years of the war, the Partisan movement struggled to translate these principles into reality. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, while the movement’s cadres were communist activists from all communities, most of its combatants were Serbs. This resulted in overlaps with the Chetnik movement and some Partisans participating in violence against non-Serb populations. Non-Serb communist activists had difficulties being accepted by their men and, as a result, some Muslim communist activists even had to adopt Serb surnames. The Partisans also chose to form exclusively Muslim units in some places, but these were small in scale and short-lived.

Nevertheless, beginning in this period, the KPJ made sure that the Muslim community was represented in the governing bodies of the Partisan movement. One of the few Muslim politicians to have joined the Partisans at that stage, former JMO senator Nurija Pozderac, was elected vice president of the first session of the Anti-Fascist Council for People’s Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ), which was held in Bihać on November 26 and 27, 1942.

In his speech to the council, Pozderac declared: “All Muslims must know that the victory of our enemies, of the enemies of the struggle for people’s liberation, would signify the complete extermination of Muslims, and this is why the struggle for people’s liberation is the only path [possible] for all Muslims.”28 Even at this early stage, the Partisan movement thus endeavored to present itself as a guarantor of the physical security of the Muslim community. In its final declaration, the AVNOJ repeated this argument, addressing Muslims thusly:

Muslims! You have felt at your own expense the full intensity of the Ustasha crimes committed against Serbs in Bosnia, in Herzegovina and in the Sandžak, when the blood-thirsty Chetnik gangs began to cut the throats of your children and your wives and to burn down your homes and your villages. The leadership of the Yugoslav Muslim Organization deceived you during those days of extreme troubles and misfortune, caused by the Ustashas massacring the Serb population… Muslims must no longer be a booty to be fought over by Great Serb pillagers and by [unreadable: Great Croat?] twisted monsters, all to reign over one group or another. All of you—Serbs, Croats and Muslims—need sincere and fraternal cooperation, so that Bosnia-Herzegovina as the entity of our fraternal community can move forward for everyone’s satisfaction with no differences of religion or party.29

In addition to ensuring their physical security, the Partisan movement thus offered Muslims recognition for Bosnia-Herzegovina as a distinct territorial entity within the future Yugoslav state. In so doing, the movement adopted the demand for autonomy for Bosnia-Herzegovina that had previously been advocated by the traditional Muslim elites.

By the end of 1942, the Partisan movement had stopped its Serb combatants from committing acts of violence against non-Serb populations. At the same time, several new agreements between the occupation forces, the Ustasha authorities and the Chetnik movement left the Muslims defenseless from attacks by the Chetniks. A logical consequence was that many Muslims began to join the Partisans, initially in western Bosnia, then in the rest of Bosnia-Herzegovina. In the following years, the Partisan movement incorporated many Muslim combatants from the regular Croatian Army, Muslim militias, and even the 13th SS Division. On some occasions, entire formations rallied the Partisans in one go, such as when the Tuzla garrison joined in October 1943 or Huska Miljković’s Muslim militia from the region of Cazinska Krajina (near Bihać) in February 1944. The Partisan movement’s growing presence in the Muslim community resulted in the formation of Muslim majority units, such as the 8th Brigade of Krajina, formed in western Bosnia in December 1942. Some “Muslim brigades” (muslimanske brigade) were also founded, such as the 16th Muslim Brigade, formed in eastern Bosnia in September 1943, or the 1st and 2nd Muslim Brigades, formed in early 1944 in western Bosnia. By duplicating the communitarian structure of Bosnian society in their military organization, the Partisans were endeavoring to reassure the Muslim populations and to facilitate the incorporation of Muslim combatants. The Partisan movement used a similar approach with the Croat community, with the 18th Croat Brigade being created in October 1943 in Tuzla. As community ties were taken into account, so too were religious practices. Each brigade had an officer for religious matters (vjerski referent), and Islamic dietary restrictions were respected in the Muslim brigades. Lastly, the Partisans were able to rely on some religious leaders to help mobilize the Muslim community. Muhamed Kurt, the mufti of Tuzla, rallied the movement when the Partisans captured Tuzla in October 1943, and several ‘ulama’ took part in the sessions of the AVNOJ. In March 1944, thirty-four imams from western Bosnia denounced the ‘ulama’ that had helped recruit Muslims for the Ustashas and the SS, declaring that in so doing, they had “left Islam.” These imams reassured the population that the Partisan movement respected the Islamic faith, and proclaimed, “our faith, sublime Islam, orders that we shall fight against the assassins of liberty and the enemies of the faith [namely] the Germans, the Chetniks and the Ustashas.” They then assimilated the struggle for people’s liberation with jihad, stating, “those who lose their lives in this holy war will be šehits [martyrs of the faith].”30

As the Partisan movement gained strength within the Muslim community, a growing number of Muslim notables rallied it. This was clearly apparent in the composition of the Provincial Anti-Fascist Council for the People’s Liberation of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Zemaljsko antifašističko vijeće narodnog oslobođenja Bosne i Hercegovine—ZAVNOBiH), which met for the first time on November 25 and 26, 1943 in Mrkonjić Grad. Of 172 delegates, forty-one were Muslims: alongside communist militants from before the war, such as Avdo Humo, Hasan Brkić, and Pašaga Mandžić, other delegates included a former JMO deputy, a former sub-prefect, three former officers of the Croatian Army and the DOMDO, a professor from the Higher Islamic School for Theology and Shari‘a Law, two professors of Islamic religion, a writer, and many others from more ordinary occupations. The KPJ’s preoccupation with re-establishing the communitarian structure of Bosnian society was visible not just in the composition of the ZAVNOBiH. It was also the reason behind the party’s constant emphasis on equality between Serbs, Muslims, and Croats. Hence, in its final resolution, the first session of the ZAVNOBiH declared that all the peoples of Bosnia-Herzegovina “want their country—which is neither Serb, nor Croat, nor Muslim, but Serb and Muslim and Croat—to be a free and fraternal Bosnia-Herzegovina where full equal rights and equality are guaranteed for all Serbs, Muslims and Croats.”31 In opposition to the Ustasha and Chetnik nationalist projects, the Partisan movement reaffirmed the multiethnic character of Bosnian society. Moreover, the Muslim delegates to the ZAVNOBiH addressed a special appeal to their “Muslim brothers,” reminding them that:

Muslims will save themselves from extermination and will ensure a better future for their children if they invest their strength in the common struggle with the Serb and Croat peoples against the foreigners and their mercenaries. Muslims must follow the path of the Muslim Partisans who are fighting in the people’s liberation movement, the only true protector of the Muslim community.32

Here again, the Partisans were presented as the Muslim community’s new protectors.

This special treatment for the Muslim community would be found again in the second session of the ZAVNOBiH, from June 30 to July 2, 1944 in Sanski Most. In his introductory speech, communist leader Đuro Pucar stated that Muslims were not rallying the Partisan movement due to a deep-seated political conviction, but because of “a specific arrangement based on the conviction that the people’s liberation movement is the only one that can save the Muslim community from the difficult situation that they have faced up until now.” To explain why it had taken so long for Muslims to join the movement, Pucar emphasized that “the Muslims have, due to their socio-historical situation and their political education at the time of [the first] Yugoslavia, developed certain peculiarities that strengthened, in an unbelievable manner, their sentiment of being a separate group.” He therefore advocated relying on the notables that had joined the Partisan movement in order to create a representative body specifically for the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina, aimed at facilitating their integration into the people’s liberation struggle.33 In September 1944, the Muslim delegates to the ZAVNOBiH issued a new appeal, urging Muslims to join “the people’s liberation movement that has saved us, Muslims, from annihilation,” and emphasizing, “only in this way can we ensure our interests and our future, only in this way can we ensure that we will have a worthy place in the new state.”34 Eight months later, the Main Muslim Committee (Glavni odbor Muslimana) was created, grouping together the Muslim cadres of the Partisan movement in Bosnia-Herzegovina. This communitarian body, attached to the People’s Liberation Front (Narodno-oslobodilački front—NOF) had no equivalent within the Serb or Croat communities.35

By re-establishing the communitarian structure of Bosnian society, the Partisan movement also recognized Bosnia-Herzegovina’s status as a constituent of the future Yugoslavia. However, for a long time, the KPJ was evasive as to the exact status that it intended to give the province. The communist leaders of Bosnia-Herzegovina were in favor of equal status to the other constituents of the future federal state, but some members of the KPJ leadership—such as Moša Pijade and Milovan Đilas—were in favor of transforming Bosnia-Herzegovina into an autonomous province of Serbia. This debate remained open until Tito made the final decision just before the second session of the AVNOJ, held in Jajce from November 21 to 29, 1943. During this session, the Democratic Federative Yugoslavia was proclaimed, with Bosnia-Herzegovina becoming one of its six constituent republics, alongside Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia (see Map VI). The Partisan movement thus sheltered Bosnia-Herzegovina from the Serb and Croat nationalist claims and turned it into a distinct territorial entity within the new Yugoslav state. At around the same period, the KPJ leaders were apparently tempted to recognize the territorial autonomy of the Sandžak, but they ultimately decided to divide it between Serbia and Montenegro.36

To justify their decision to elevate Bosnia-Herzegovina to the rank of constituent republic of the Yugoslav state, the communist leaders stated that this was the only way to ensure equality between the Serbs, Muslims, and Croats of Bosnia-Herzegovina and thus to bolster the stability of Yugoslavia. In an article dated April 1945, Rodoljub Čolaković wrote that the war had shown that “Bosnia-Herzegovina is neither Serb, nor Croat, but both Serb and Croat, as well as Muslim.” Čolaković then explained that, for this reason, “Bosnia-Herzegovina could not be divided because this would have meant dividing a close-knit entity, a whole that has long had its own life,” and that it was therefore decided to make Bosnia-Herzegovina a constituent of the new Yugoslavia. Also according to Čolaković:

Map VI Communist Yugoslavia (1943–91).

This solution for the question of Bosnia-Herzegovina will strengthen the new Yugoslavia because the continued fraternal relations between Serbs and Croats in Bosnia-Herzegovina will, first and foremost, be reflected in the relations between Serbs and Croats in [all of] Yugoslavia, [and therefore] in the relations between the two most important nations in Yugoslavia.37

While justifying Bosnia-Herzegovina’s elevation to the rank of constituent republic, Čolaković’s article also highlights a basic ambiguity in the Partisan movement, namely, the political status of the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Indeed, in the same article, Čolaković wrote:

In Bosnia-Herzegovina, as everyone knows, there live two nations: the Serbs and the Croats, and the Muslims who are undoubtedly of the Slavic race. They will be given the possibility to determine what nation they belong to, peacefully and gradually.38

Čolaković thus appeared to share the dominant conception since the late nineteenth century, whereby Bosnian Muslims could only be identified nationally as Serbs or Croats. But things were more complex. In a brochure entitled Our Muslims and the Struggle for People’s Liberation, the same Čolaković was close to recognizing Bosnian Muslims as a separate national identity. In the new Yugoslavia, he wrote, “nobody will force them to be what they are not, Serbs or Croats, nobody will touch their faith or their customs, nobody will consider them responsible for the Ustasha misdoings.”39 More generally, the proclamations of the Partisan movement in Bosnia-Herzegovina were addressed systematically to Serbs, Muslims, and Croats, often using a capital M (Muslimani rather than muslimani) to refer to Muslims, but they never spoke of a “Muslim nation” (muslimanski narod) the way they spoke of Serb and Croat nations. This refusal to regard the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina as a separate nation was very clear in the case of some communist authors. For example, Veselin Masleša wrote in 1942 that Muslims “have none of the necessary objective qualities that make a nation, and—a logical consequence of objective qualities—they do not have a subjective awareness of themselves as a nation.” Masleša therefore considered “all attempts to create a ‘Bosnian’ or even ‘Muslim’ nation [to be] destined to fail, because nations are not created by administrative fiat.”40 At the end of the war, the KPJ thus recognized the existence of a distinct Muslim community, but did not grant it the status of a nation. As a result, the new Yugoslavia would have six constituent republics, but only five constituent nations: the Slovene, Croat, Serb, Montenegrin, and Macedonian nations. The KPJ had managed to become the protector of the Bosnian Muslims, but it remained puzzled about their political status.