After the war, the victorious Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) began to build a new Yugoslavia, using the Soviet Union as its model. While the other communist regimes of central and eastern Europe tolerated a multiparty system for a certain period of time, Tito’s KPJ became almost immediately a single party. On November 11, 1945, the People’s Front led by the KPJ won 90.5 percent of votes in the election for the Constituent Assembly. On November 29, this assembly abolished the monarchy and proclaimed the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia (Federativna narodna republika Jugoslavija—FNRJ). In the following years, the communist authorities smothered all political opposition, attacked religious institutions and developed various mass organizations, such as the Women’s Antifascist Front (Antifašistički front žena—AFŽ) and the Unified League of Antifascist Youth (Ujedinjeni savez antifašističke omladine—USAO).

In this context, the main threat for the new Yugoslav authorities quickly proved to be their worsening relationship with the Soviet Union, due to Yugoslavia’s aggressive foreign policy. Going against Stalin’s advice, Yugoslavia claimed the city of Trieste as Yugoslav territory, supported the communist guerrilla in Greece, and considered creating a Balkan federation with Bulgaria and Albania. As a result, on June 28, 1948, the KPJ was excluded from Cominform and, in the months to follow, an aggressive anti-Yugoslav campaign was waged in the Soviet bloc countries. This threatened the KPJ’s unity: the supporters of Moscow represented around 20 percent of the party membership, and 30,000 of these “Cominformists” were sent to labor camps. However, in an initial period, the split between Tito and Stalin merely strengthened the Stalinist zeal of the Yugoslav leaders, who thus sought to counter accusations of “revisionism” levied against them. From the end of the Second World War until the mid-1950s, communist Yugoslavia was at the same time the most dutiful and the most turbulent pupil of the Stalinist Soviet Union. This painstaking imitation of the Soviet model could be seen in the economy, as the new Yugoslav authorities decreed a radical agrarian reform in 1945, nationalized industry in 1946, and adopted the country’s first five-year plan in 1947. Lastly, they began collectivization of farmland in 1949, but faced with the risks of rural unrest, they gave up this process four years later. Therefore, apart from Poland, Yugoslavia was the only country of central and eastern Europe whose agricultural sector remained in the hands of smallholders.

The area in which the Soviet influence was the most visible and lasting was undoubtedly the policy of nationalities. Proclaimed on January 31, 1946, the Constitution of the new Yugoslavia recognized six republics (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia), along with an autonomous province (Vojvodina) and an autonomous region (Kosovo), both within the Republic of Serbia (see Map VI). In so doing, the Yugoslav communists looked for inspiration in the Soviet Union’s division into federal republics, autonomous republics, and autonomous regions, and transformed Yugoslavia into something of a Soviet-style plurinational mini-empire. The KPJ was divided into republican communist parties, although this division remained largely formal until the 1960s. In parallel, the Yugoslav communists adopted the definition of “nation” given by Slovene communist leader Edvard Kardelj—and inspired by Stalin—whereby a nation is:

A specific social community based on the social division of labour of the capitalist period, on a compact territory and within the framework of a shared language and, more generally, tight ethnic and cultural ties.1

On this basis, they distinguished five constituent nations of the Yugoslav federation: the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes—already recognized as specific groups in the first Yugoslavia—plus the Macedonians and the Montenegrins, who had been regarded as Serbs in the interwar period. Lastly, the Yugoslav communists recognized the existence of several national minorities, including the large Albanian minority settled mainly in Kosovo and western Macedonia.

The break with the Soviet Union did not affect this general architecture of the Yugoslav federation, but initially, it prompted the KPJ to insist on the idea that building a socialist society, by eliminating the national bourgeoisies, would allow for rapprochement between the South Slavic nations. This “socialist Yugoslavism” (socijalističko jugoslovenstvo) was also formulated by Kardelj:

It is not an artificial merging of languages and cultures, nor is it the creation of a new Yugoslav nation of the classic sort, but rather a development and strengthening of the workers’ socialist community of all the nations of Yugoslavia, the affirmation of their shared interests on the basis of socialist relations [of production].2

After the failure of the first Yugoslavia and its integral Yugoslavism, the KPJ endeavored to lay the foundations for a new socialist community of the Yugoslav nations. Accordingly, Serb and Croat linguists signed an agreement in Novi Sad in December 1954, officially recognizing the existence of a single Serbo-Croatian language—or Croato-Serbian—with two alphabets (Cyrillic and Latin) and two pronunciations (ekavica and ijekavica).3

Once again, Bosnia-Herzegovina found itself at the heart of the Yugoslav state’s contradictions. In November 1945, the People’s Front won in this republic a record score of 95.2 percent of votes, but the KPJ noted a trend for some voters to prefer candidates from their own communities.4 Initially called “Federal Bosnia-Herzegovina” (federalna Bosna i Hercegovina), Bosnia-Herzegovina was promoted to the status of constituent republic of Yugoslavia on February 8, 1946, and adopted its own Constitution on December 31, 1946. This Constitution of Bosnia-Herzegovina did not specifically enumerate its constituent nations, stating only: “in the People’s Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, its nationalities are in all respects equal in rights” (Article 11).5 In fact, only the Serbs and Croats were recognized as constituent nations. Bosnia-Herzegovina was thus in a peculiar position, as it was the only republic without an eponymous nation, whereas its two constituent nations had their political and cultural “centers of gravity” outside its borders. The relative recognition that the Muslim community had enjoyed during the war was quickly jeopardized, and the Main Muslim Committee (Glavni odbor Muslimana) created in May 1945 was disbanded eighteen months later. Likewise, the Muslim cultural society Preporod (“Rebirth”) was founded in September 1945 with the merger of the societies Gajret and Narodna uzdanica, but it was dissolved four years later, at the same time as the Serb society Prosvjeta and the Croat society Napredak. The Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina were relegated to “national indetermination”, as shown in the first post-war population censuses.

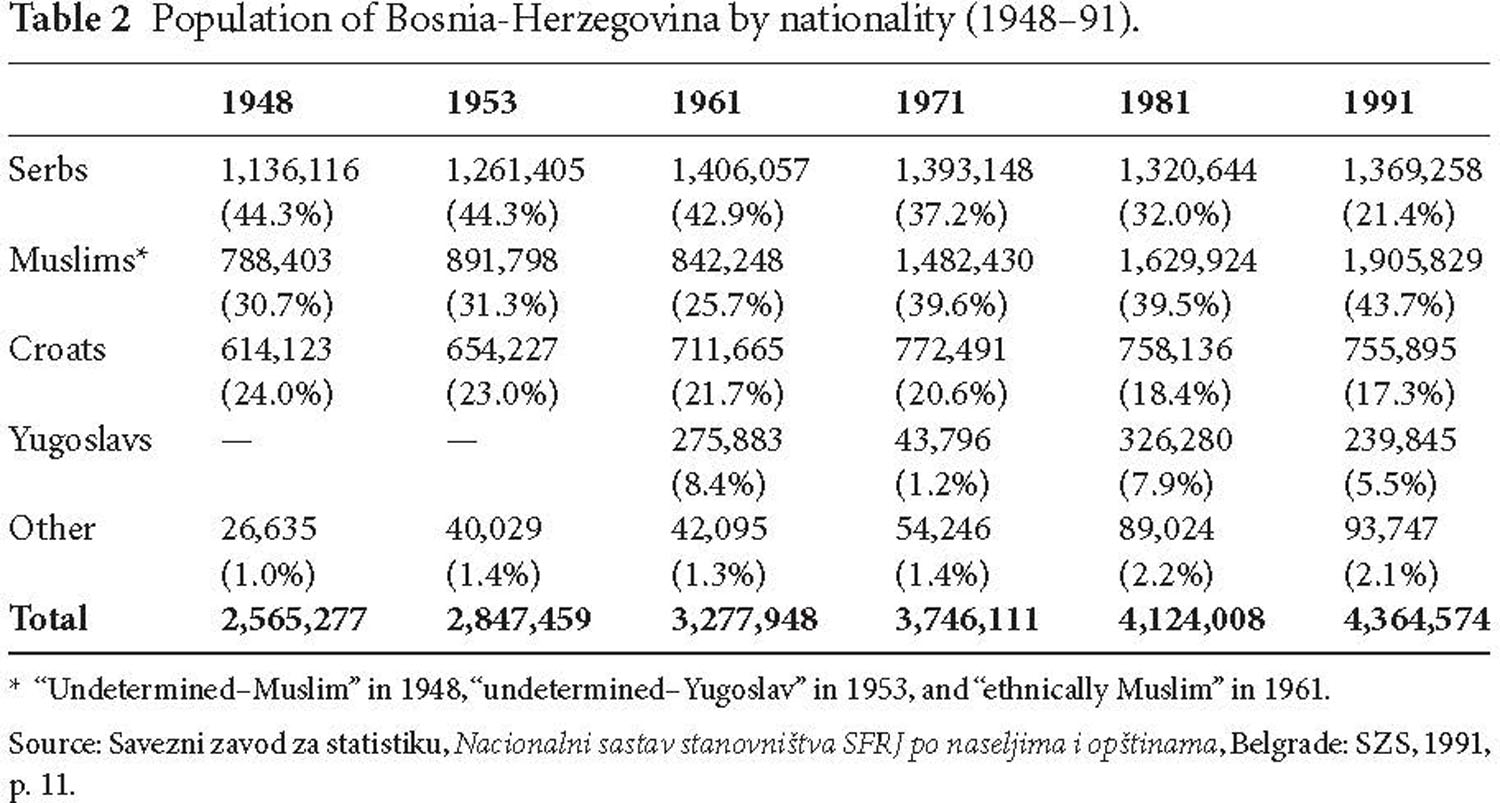

During the 1948 census, Bosnian Muslims could declare themselves to be “undetermined–Muslim,” “Serb–Muslim,” or “Croat–Muslim.” In this census, 788,403 chose the first category, compared with 71,991 declared to be Serb–Muslim and 25,295 Croat–Muslim. At the time, Bosnian Muslims represented 30.7 per cent of the total Bosnian population, versus 44.3 per cent for Serbs, and 23.0 per cent for Croats (see Table 2). Five years later, at the height of socialist Yugoslavism, Bosnian Muslims—which the communist authorities intended to nationalize rapidly—could declare themselves to be “undetermined–Yugoslav,” “Serb,” or “Croat.” To justify this choice, communist leader Moša Pijade wrote:

The term “Muslim” designates belonging to the Muslim religion, and has no connection with the question of nationality… No one has ever doubted the fact that the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Sandžak are of Yugoslav origin, and belong ethnically to the Yugoslav community. This is why those who have determined themselves to be Serbs or Croats will register as “Serb” or “Croat”, and those who have not precisely determined [their nationality] will register as “undetermined–Yugoslav”… This will put an end to the non-scientific and backward practice of mixing religious identity and the determination of nationality.6

In the 1953 census in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 891,798 declared themselves to be “undetermined–Yugoslav,” i.e. 31.3 percent of the total population, compared to 44.3 percent Serb and 23.0 percent Croat (see Table 2).7 Thus, in the first decade after the war, the national indetermination that had characterized Bosnian Muslims since the nineteenth century returned to the forefront.

In December 1945, during the Constituent Assembly’s debates, Muslim deputy Husaga Ćišić protested the fact that Bosnia-Herzegovina was deprived of its own eponymous nation, calling for recognition of the “Bosnians” (Bosanci) as the sixth constituent nation of the Yugoslav federation, albeit without clearly stating whether this new nation would encompass only Muslims or all the inhabitants of Bosnia-Herzegovina. But Ćišić remained alone in his endeavor, and communist leader Milovan Đilas retorted: “The Parliament cannot examine the question of whether the Muslims are a national group or not… This is a theoretical question on which people can debate in this fashion or that, but in no way can it be resolved by decree.”8 Moreover, the members of the Constituent Assembly paid less attention to Ćišić’s protests than to a letter from the ulema-medžlis asking that the new Constitution maintain the autonomous management of waqfs and the validity of Shari‘a law for family affairs. Against a backdrop of radical political upheaval, the Islamic Religious Community (Islamska vjerska zajednica) thus attempted to preserve the religious institutions that had, since 1909, formed the backbone of the Muslim community as a non-sovereign and protected religious minority. Yet as part of their overall anti-religious policy, the communist authorities began systematically to dismantle these institutions: Shari‘a courts and the Higher Islamic School for Theology and Shari‘a Law were shut down in 1946, religious classes were removed from public schools in 1948, the mektebs (Qur’anic schools) were closed in 1952, and the Gazi Husrev-beg Madrasa in Sarajevo was the only madrasa to remain open throughout the communist period. Lastly, the waqfs were nationalized over a period from 1945 to 1958.

Not content to weaken the Islamic religious institutions, the communist authorities attempted to take control of them. As early as 1945, some religious dignitaries were tried for collaboration, including Mustafa Busuladžić, sentenced to death and later executed, and Muhamed Pandža, sentenced to ten years of prison. In the following years, several other trials took place, including that of Kasim Dobrača and twelve other defendants in September 1947. This trial finally broke the resistance of the Islamic Religious Community, and in August 1947, its leadership agreed to adopt a new internal Constitution and to elect Ibrahim Fejić (a cleric who had rallied the Partisan movement) as Reis-ul-ulema. This brought an end to the autonomy Islamic religious institutions had enjoyed since the Austro-Hungarian period. Three years later, an Association of ‘Ulama’ of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Udruženje ilmije Bosne i Hercegovine) was founded; it declared its allegiance to the new communist power and joined the People’s Front led by the KPJ. At the same time, the Ajvatovica, a major Sufi pilgrimage in central Bosnia, was banned in 1947, as were the tarikats (Sufi orders) in 1952. Lastly, the end of the status that the Muslim community had enjoyed as a non-sovereign and protected religious minority was symbolized by the abolition of the veil for women—a subject that had given rise to such heated controversy in the interwar period. Beginning in 1947, the Women’s Anti-Fascist Front (AFŽ) launched a campaign to abandon the veil. This campaign received the support of the KPJ’s other mass organizations, the Muslim cultural society Preporod, and even the leadership of the Islamic Religious Community. After three years of intense propaganda, the communist authorities decided to use force, and on September 28, 1950, the Parliament of Bosnia-Herzegovina voted to prohibit the veil. In the following months, similar laws were passed in Montenegro, Serbia, and Macedonia. In the span of a few years, the institutional and symbolic devices that had ensured the Muslim community’s cohesion were swept away by the new regime, strengthening the feeling of identity crisis that prevailed in the first decade after the war.

In this difficult context, the Young Muslim movement (Mladi Muslimani) was revived. Having lost the protection of the disbanded association el-Hidaje, and forced into a semi-clandestine status, the Young Muslims nevertheless managed to set up a network with several hundred members. In addition to their usual activities of re-Islamization, they carried out more directly political actions such as infiltrating the cultural society Preporod in Sarajevo and preparing for an uprising in the Mostar region. Marked by the violence of the Second World War and faced with harsh anti-religious policies, the Young Muslims considered Bosnian Muslims to be threatened with physical and spiritual annihilation. Convinced that the political, intellectual, and religious elites had failed to protect the Muslims, they declared that they were taking charge of their community to lead it in combat. Thus, a proclamation by the Mostar group stated:

While a [communist] foe destroys everything Islamic, while it offends, attacks Muslims and attempts to suppress their leaders … others are making plans to exterminate us physically, just as they annihilated the Muslims in Hungary, in Lika, in Sicily and in Spain… In these difficult times, our organization is taking charge of the Muslims … for these are days of fighting for existence, days of jihad, and our organization is resolutely committed to this path.9

Therefore, the Young Muslims of the post-war period had an even stronger political bent than during the Second World War. Fiercely anti-communist, they were also opposed to any rapprochement with other South Slavs:

Enough with the choices and options [looking] towards Zagreb or Belgrade, this must be clear for everyone and especially for our intelligentsia. It has led us to everything but the defense of Islam and the Muslims. We have seen with our own eyes that the names “Croat” or “Serb” are just masks hiding a cross and a sword, with a single idea: to demolish Islam, to avenge [the Battle of] Kosovo, to rape, pillage and defeat the crescent and the star.10

As a consequence, the pan-Islamist utopia remained at the heart of a political project calling for the re-Islamization of Muslim societies, the seizure of power in each of them, and their unification in a vast pan-Islamic state. This grandiose vision mingled with the more modest goal of achieving independence for Bosnia-Herzegovina, eventually giving birth to the idea of a state that would bring together all the Muslims of the Balkans. This idea of a Balkan Muslim state explains why the Young Muslims were so interested in Pakistan, formed in 1947 from the partition of the Indian subcontinent along confessional lines. One of their clandestine newsletters was even entitled Pakistan. But the Young Muslims had little leisure to build their pan-Islamist utopia: from 1946 until 1949, they were the target of fierce repression, culminating in the trial of fourteen Young Muslims in August 1949, with four of the defendants sentenced to death. The Young Muslim movement was then completely dismantled, with most of its members either in jail or refugees abroad.

In the decades following the establishment of communist power, Yugoslav society—and within it, Bosnian society—underwent profound transformations. From 1945 onwards, the communist period corresponded with an era of accelerated modernization on all levels. First and foremost, societies that had mainly been agrarian became primarily industrial and urban. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, the proportion of farmers in the active population dropped from 80.6 percent in 1948 to 23.8 percent in 1981. Over the same period, the proportion of industrial workers rose from 9.7 percent to 34.7 percent. Although “peasants-workers” remained numerous in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the rural exodus resulted in rapid growth in cities: between 1948 and 1981, Sarajevo’s population grew from 115,000 to 380,000, and other major cities such as Banja Luka, Tuzla, Mostar, and Zenica experienced similar growth. New districts, with socialist architecture, sprouted up on the outskirts of cities, contributing to the emergence of a new urban culture. At the same time, the development of public education quickly reduced illiteracy—in Bosnia-Herzegovina, illiteracy dropped from 44.9 percent in 1948 to 14.5 percent in 1981—and brought about a higher level of education. Between 1953 and 1981, the proportion of the Bosnian population with a high school diploma rose from 4.1 percent to 21.7 percent, and those with a university education rose from 0.3 percent to 4.3 percent. A university was opened in Sarajevo in 1949, followed by others in Banja Luka (1975), Tuzla (1976), and Mostar (1977); in the early 1980s, there were more than 50,000 university students in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

These economic and social changes, which lead to higher living standards, greater leisure time, and more gender equality, fueled a veritable cultural revolution that also reshaped the way people fitted into their communities. In cities in particular, each community’s markers of cultural identity tended to disappear, and communitarian ties faded as a shared Yugoslav lifestyle gained strength. One important indicator of these transformations were mixed marriages. While such marriages were rare before the Second World War, they comprised 7.4 percent of all weddings in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1950 and 12.0 percent in 1981. However, Bosnia-Herzegovina still had one of the lowest rates of mixed marriage anywhere in Yugoslavia, and the Muslim community was clearly less exogamous than the Serb and Croat communities. More generally, modernization in the communist period came with certain imbalances between urban and rural areas, with the latter remaining partly on the sidelines of the transformations underway. Likewise, the gap widened between the most developed federal units (Slovenia, Croatia, Vojvodina, and Serbia) and the least developed ones (Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Bosnia-Herzegovina): the gross social product (i.e. output) per capita of Bosnia-Herzegovina was 83 percent of that of Yugoslavia as a whole in 1953, compared with just 67 percent in 1981. To understand why, we must look at how the Yugoslav federation evolved politically.

Beginning in the mid-1950s, Yugoslavia stopped copying the Soviet Union and gradually started to create its own model of self-managed socialism. On an economic level, self-management was introduced into the workplace and planning was combined with elements of a market economy. This economic decentralization further widened the development gap between the federal units, despite the creation in 1965 of a Federal Fund for the Development of Underdeveloped Republics and Provinces. This development gap quickly became one of the main subjects of discord between the elites of each republic. On a political level, the new Constitution adopted on April 7, 1963 created the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Socijalistička federativna republika Jugoslavija—SFRJ). Within this new entity, the federal units enjoyed greater powers, whereas Kosovo became an autonomous province.

In 1952, the KPJ was renamed the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (Savez komunista Jugoslavije—SKJ), and the People’s Front was renamed the Socialist Alliance of Working People (Socijalistički savez radnog naroda—SSRN). As from 1964, the growing autonomy of the republican and provincial leagues of communists was symbolized by the fact that their congresses were held before the federal congress. Against this backdrop, socialist Yugoslavism was abandoned in favor of “organic Yugoslavism” (organsko jugoslovenstvo), based on the idea that the constituent nations of the Yugoslav federation were complementary to one another and destined to last in the long term. In 1964, the Eighth Congress of the SKJ declared:

The erroneous opinions stating that our nations have become obsolete over the course of our socialist development and that it is necessary to create a unified Yugoslav nation [are] the expression of bureaucratic centralism and unitarism. Such opinions usually reflect an ignorance of the political, social, economic and other functions of the republics and autonomous provinces.11

Internationally, communist Yugoslavia joined with India, Egypt, and Indonesia to found the Non-Aligned Movement, hosting its first summit in Belgrade in 1961. Lastly, Yugoslavia started a program to liberalize its cultural and religious policies, and in 1965, Yugoslav citizens won the right to travel abroad. Over the following decades, nearly one million of them went to work in Western Europe.

These transformations of communist Yugoslavia in the 1960s also corresponded to a confrontation between the political elites that had risen to power during the war, who were mainly Serb and were attached to a centralized political system, and the new technocratic elites, who aspired to decentralization and liberalization of the communist system. In July 1966, Aleksandar Ranković, the head of the political police, was removed from power. This decision, approved by Tito himself, marked a temporary victory for the liberals who dominated the Leagues of Communists of Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, and Macedonia. Reforms then gathered pace, along with cultural and political liberalization, and a system of multiple candidates was even tested during the 1967 and 1969 elections. In 1969, each federal entity was given its own Territorial Defense (Teritorijana odbrana—TO), intended to assist the Yugoslav People’s Army (Jugoslovenska narodna armija—JNA) in the event of external aggression. Yet there was also an upsurge in national tensions and demands in the Yugoslav space in the late 1960s. In November 1968, Kosovo Albanians held demonstrations demanding that the autonomous province be made into a republic. These protests were severely put down. Moreover, between 1967 and 1971, the liberals of the League of Communists of Croatia grew closer to the nationalist elements of the cultural association Matica hrvatska to demand virtual independence for Croatia. Here again, Tito intervened personally, putting a decisive end to this “Croat Spring” in December 1971, while also sidelining the liberal leaders of the League of Communists of Serbia. However, this move to take back control of the situation did not lead to recentralization of the Yugoslav political system; on the contrary, it coincided with even more power being devolved to the republics and autonomous provinces.

This “confederalization” of communist Yugoslavia, symbolized by the new Constitution of February 21, 1974, made it a highly decentralized plurinational state, whose central government retained control only over foreign policy and defense, and whose head of state, Marshal Tito, was the final arbitrator in conflicts between federal units obsessed with their own prerogatives. Given these arrangements, conflicts of an economic or political nature inevitably took on a national dimension, in relations between republics and within the republican or provincial apparatus whenever several national communities coexisted inside the same federal unit. The widespread application of the “national key” (nacionalni ključ) in distributing positions of responsibility fueled powerful clientelistic networks within each community, while also helping rekindle feelings of national belonging and rivalry—inside a socialist system that was originally supposed to erase such feelings. This use of national quotas also transformed each population census into a period of intense mobilization and competition between national groups. This is the context underlying the gradual recognition given to the Muslim nation between 1961 and 1974.

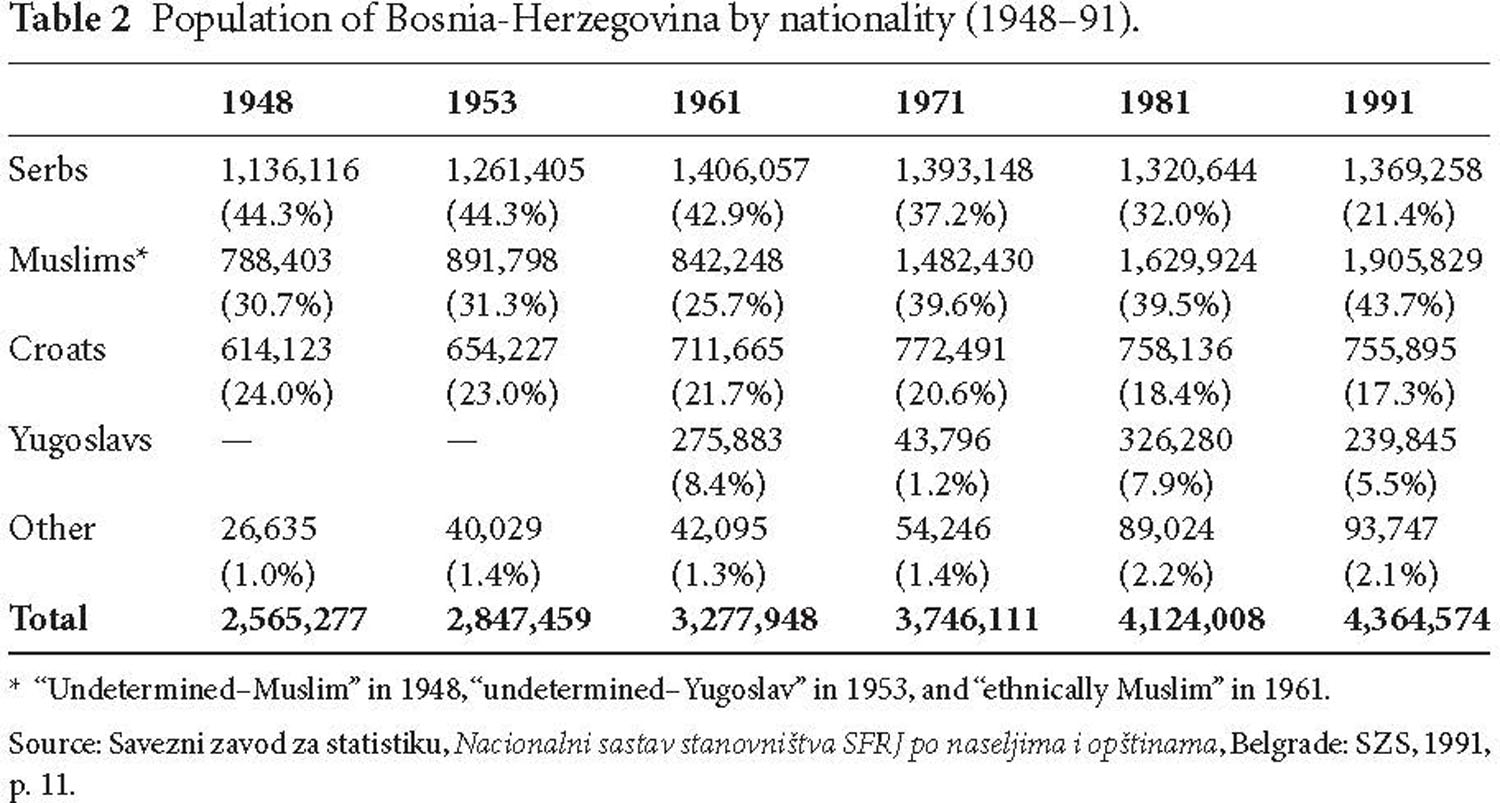

In the communist period, the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina—especially Muslim women—won access to education and salaried employment on a massive scale, and were thus among the primary beneficiaries of Yugoslavia’s modernization. The Muslim community’s social progress was also reflected in the national composition of the League of Communists of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Savez komunista Bosne i Herzegovine—SKBiH). In the 1950s, this league was clearly dominated by Serbs. At the same period, a majority of Muslim communist leaders declared themselves to be of Serb nationality. Thus, in the 1956 Who’s Who of Yugoslavia, David Dyker has counted 61.5 percent of Muslim leaders describing themselves as Serbs, versus 16.6 percent as Croats, 8.6 percent as “undetermined,” and 12.6 percent indicating no nationality.12 As from the 1960s, however, the SKBiH gradually became more representative of the three main communities of Bosnian society, as new Muslim and Croat elites emerged thanks to the communist modernization (see Table 3).

Table 3 National composition of the League of Communists of Bosnia-Herzegovina (1946–84).

| Serbs | Muslims | Croats | |

| 1946 | 69.1% | 20.3% | 8.5% |

| 1948 | 62.4% | 24.3% | 11.5% |

| 1961 | 54.7% | 30.2% | 11.9% |

| 1971 | 53.5% | 28.3% | 11.1% |

| 1984 | 42.1% | 34.6% | 11.3% |

Source: Nedim Šarac (ed.), Istorija Saveza komunista Bosne i Hercegovine—knjiga 2, Sarajevo: Institut za istoriju, 1990, pp. 31, 47, 192, and 236.

This transformation corresponded to the evolution of the SKJ as a whole. Until the mid-1960s, the SKBiH was dominated by Serb politicians who had risen to prominence during the war, such as Đuro Pucar and Rodoljub Čolaković, who defended centralist stances close to those of Aleksandar Ranković. However, Ranković’s downfall coincided with Pucar’s and Čolaković’s fall from grace in Bosnia-Herzegovina, while a new generation of communist leaders came to power, such as Hamdija Pozderac, a Muslim and the son of JMO senator Nurija Pozderac, the Croat Branko Mikulić, and the Serb Milenko Renovica. These new Bosnian communist leaders were passionate defenders of the prerogatives of their republic, while remaining scrupulously faithful to Titoist orthodoxy. The communist modernization and confederalization of Yugoslavia thus allowed for new political and intellectual elites to emerge, paving the way for the crystallization of a Bosnian Muslim national identity. Meanwhile, the abandonment of socialist Yugoslavism enabled this new mode of national identification to become widespread, as shown notably by the change in population census results. In 1961, the category “Muslim—ethnic belonging” (Muslimani—etnička pripadnost) was added to the census. This category was defined in these terms:

Muslim, in terms of nationality, refers to an ethnic and not confessional belonging. The only people who should give this response are those of Yugoslav origin who consider themselves Muslims in terms of ethnicity. As a result, neither the members of non-Yugoslav nationalities, such as the Albanians or the Turks, nor Serbs, Croats, Montenegrins, Macedonians and others that consider themselves to be members of the Islamic religious community [should give this response]. These individuals should respond according to their nationality, i.e. Albanian, Turk, Serb, Croat, Montenegrin, Macedonian, etc., regardless of their religion. As the response “Muslim” designates an ethnicity and not a religion, individuals with no religion can also give this response if they consider themselves to belong to this ethnic group.13

This definition is in complete contradiction to the stances that Moša Pijade had defended eight years earlier. In the 1961 census, in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 842,248 people declared themselves to be of Muslim ethnicity, but 275,883 others declared themselves to be Yugoslav, which suggests that a large number of Bosnian Muslims continued to opt for the latter category (see Table 2). From a legal perspective, the recognition of a Muslim nation remained hesitant as well, as the new Bosnian Constitution of April 10, 1963 merely affirmed the liberty, equality, and fraternity of the “Serbs, Muslims and Croats,” without clearly mentioning their status as constituent nations.14

It was not until Aleksandar Ranković and the old guard of the Party in Bosnia-Herzegovina left the scene that the Muslim nation became fully and entirely recognized as such. Most often, the event officially recognizing this new nation is considered to have taken place on May 17, 1968, when the Central Committee of the SKBiH stated:

Experience has shown the harmfulness of the various forms of pressure and injunction left over from an earlier period, aimed at forcing the Muslims to determine themselves nationally as Serbs or Croats, for it was apparent in the past, and current socialist practice confirms, that the Muslims constitute a separate nation.15

This official recognition did not fail to trigger hostile reactions in the neighboring republics. During the 1971 census, for example, a controversy erupted between the SKBiH and the League of Communists of Macedonia regarding the Slavophone Muslims of Macedonia and their right to declare their nationality as Muslim. At the same time, the “Muslim” national name was promoted intensely in Bosnia-Herzegovina, with the media and organizations in charge of the census also striving to delegitimize the terms “Yugoslav” and “Bosnian.” The former was presented as a supranational category, and the latter as a regional identity with the same value as “Dalmatian” or “Slavonian.”

The Commission for Interethnic Relations of the SSRN, presided over by the Muslim Atif Purivatra, played a central role in this mobilization campaign in favor of the “Muslim” national name. Ultimately, in 1971, 1,482,430 people in Bosnia-Herzegovina declared themselves to be Muslims (i.e. 39.6 percent of the total population), compared to 1,393,148 declaring themselves to be Serbs (37.2 percent), 772,491 Croats (20.6 percent), and 43,796 Yugoslavs (1.2 percent) (see Table 2). Thus, the 1971 census was a major turning point in the political history of the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina. During this census, the Bosnian Muslim population mobilized on a massive scale in favor of a new mode of national identification. As a result, for the first time in history, Bosnian Muslims stood out as a nation, separate from the Serb and Croat nations. Moreover, for the first time since 1878, they formed the largest population segment in Bosnia-Herzegovina, to the detriment of the Serbs, whose share of the total Bosnian population had declined from 44.3 percent in 1948 to 37.2 percent in 1971. This reversal in the demographic balance of powers between Serbs and Muslims was even more obvious in the 1981 and 1991 censuses (see Table 2). This partly reflected the changes in the national identification of some Muslims, but was also attributable to their higher birth rate, the result of a later demographic transition, and to a higher rate of emigration of Serbs and Croats from Bosnia-Herzegovina to the neighboring republics of Serbia and Croatia. Lastly, between 1961 and 1991, Slavophone Muslims outside Bosnia-Herzegovina also began to adopt the Muslim national identification, with the number of people recorded as Muslims rising from 83,811 to 173,871 in Serbia proper (i.e. outside the autonomous provinces), from 30,665 to 89,932 in Montenegro, from 8,026 to 57,408 in Kosovo, and from 3,002 to 47,790 in Macedonia.16

A scant twenty-five years after the communist authorities had done away with the Bosnian Muslim community’s status as a non-sovereign and protected religious minority, this community was elevated to the rank of constituent nation of Bosnia-Herzegovina and of the Yugoslav federation. Following the 1971 census, the Muslim nation represented the most populous nation in Bosnia-Herzegovina and the third largest constituent nation of Yugoslavia, with 1,729,932 members across all of Yugoslavia, i.e. 8.4 percent of the total population. Three years later, the Muslims’ constituent nation status was explicitly stated in the Yugoslav Constitution of February 21, 1974 and the Bosnian Constitution of February 25, 1974. The latter document defined Bosnia-Herzegovina as the state “of the workers and citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina, of its nations—Muslims, Serbs, and Croats, and of the members of the other nations and nationalities who live there.”17 This radical reversal in fortune was partly due to the fact that the dismantling of the religious institutions that had previously structured the Muslim community in Bosnia-Herzegovina had created a void, which the new Muslim national identity then filled. However, it resulted mainly from a twofold political process strengthening the prerogatives of the republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina and giving birth to new Muslim political and intellectual elites. Now, we will look at how these new elites defined the Muslim national identity, and the paradoxes that they had to confront.

The recognition of the Muslim nation in the 1960s and 1970s took place with Tito’s approval, and was supported by a large majority of the SKBiH’s leaders (Muslims, Serbs, and Croats combined), who regarded this as a means to strengthen the political subjectivity of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Muslim protagonists, thus, did not drive this process alone. However, the task of constructing a national identity that would buttress the new political status of the Bosnian Muslims fell to the Muslim political and intellectual elites. This cultural undertaking, officially described as a process of “national affirmation” (nacionalna afirmacija), relied on several scientific institutions, such as the Provincial Museum, the Faculties of Philology and Political Science at the University of Sarajevo, the Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia-Herzegovina (created in 1964), and the Institute for the History of the Workers’ Movement, inaugurated a year later. The results of this work were published in the Sarajevan journals Pregled (“Panorama”), Odjek (“Echo”), and Život (“Life”), or in the collections of publishing house Svjetlost (“Light”).

The Muslim “national affirmation” began with a rejection of the past attempts at assimilating Bosnian Muslims into the Serb and Croat nations. For example, Atif Purivatra, a historian and president of the Commission for Interethnic Relations of the Socialist Alliance of Working People of Bosnia-Herzegovina, stated:

[Muslims] are not, in the national sense, Serbs, Croats, or “undetermined” but … constitute a particular ethnicity in the Serbo-Croatian linguistic area, equivalent to the Serb, Montenegrin and Croat nations.18

To demonstrate this, Muslim politicians and intellectuals endeavored to provide the Muslim nation with the origin myth and historical continuity that would allow it to fully occupy its place in the community of Yugoslav nations. Rediscovering the markers of cultural identity produced during the Austro-Hungarian and interwar periods, they emphasized the South Slavic origins of Bosnian Muslims and insisted on the “bogomilism” of the medieval period as a central explanation for their conversion to Islam. This emphasis on religion as a founding element of national identity is hardly consistent with the definition of a nation as given by Edvard Kardelj,19 but Marxist dogma reappeared in the handling of later periods of Muslim history. Thus, the specialist in Ottoman history Avdo Sućeska insisted with others on the autonomy that Bosnia had enjoyed during the Ottoman period, but he added that, “unlike the non-Muslim population, which found itself mainly in a situation of serfdom and in a subordinate political position, Muslim society was complete and self-sufficient, in other words, it comprised all estates and all social groups.”20 The influence of Marxist ideology was even clearer in the explanations given for why a Muslim national identity had taken shape so belatedly; this was attributed to the reactionary nature of the Muslim landholding elites, and the hegemonic claims of the Serb and Croat bourgeoisies. Lastly, to legitimize the emergence of a Muslim nation in a socialist society, the proponents of this nation noted that the KPJ had—after some hesitation—recognized the specific ethnicity of Bosnian Muslims in the late 1930s already, and that the struggle for national liberation in Bosnia-Herzegovina had been waged in the name of the Serbs, Muslims, and Croats.

Hence, the 1960s and 1970s were an important period of rediscovery and reinterpretation of the markers of cultural identity created during the Austro-Hungarian and interwar periods. However, the proponents of Muslim national identity came up against several major obstacles. The first involved the definition of the ties between Islam and the Muslim national identity. Indeed, they had to show that Islam lay behind the specific identity of Bosnian Muslims, while not depicting them as a mere religious group. To this end, Muslim politicians and intellectuals noted that the Serb and Croat national identities had also crystallized around religious symbols and explained that Islam had given birth to numerous markers of cultural identity that had lost their religious meaning in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Thus, according to Atif Purivatra,

“Muslim” as a concept triggers an association with a member of the Islamic religion, which is one of the world’s largest religions. However, in the Yugoslav space and particularly in Bosnia-Herzegovina, history has given this concept many new meanings, which in our era extend and even modify the initial meaning.21

To mark this dissociation between the Muslim identity in the confessional and the national sense of the word, the proponents of the Muslim national identity emphasized that the name “Muslim” should be written with a lower-case “m” when referring to the religion, and with a capital “M” when referring to the nationality. In this view, the national category “Muslim” (with a capital “M”) also encompassed non-believers, and the recognition of the Muslim nation would even help secularize Bosnian Muslims. In December 1969, the Central Committee of the SKBiH observed that recognizing the Muslim nation “reduces Muslimness [muslimanstvo] to an ethnic category and frees it of the religious burden that is still present in the concept ‘Muslim’ in the minds of many Muslims.”22 Furthermore, to justify this recognition, intellectuals Kasim Suljević and Salim Ćerić compared the situation of Muslims with that of Jews, another religious community that had been elevated to the rank of nation.23 However, despite the difference in capitalization between members of the Umma and members of the Muslim nation, the Muslims were still the only Yugoslav constituent nation to have a national name with a religious origin. This peculiarity created a large number of ambiguities and paradoxes, as we will see later on with regard to the Islamic Religious Community.

Endeavoring to detach the national name “Muslim” from its religious roots, Muslim politicians and intellectuals also had to justify the fact that this term was preferable to “Bosniak” (Bošnjak) or “Bosnian” (Bosanac). To do so, the proponents of Muslim national identity emphasized the failure of Bosnism (bošnjaštvo) in the nineteenth century. The rejection of “Bosniak” or “Bosnian” as a national name coincided with renewed emphasis that Bosnia-Herzegovina had three constituent nations: Muslims, Serbs, and Croats. In this context, adopting the term “Bosniak” or “Bosnian” would amount either to identifying the whole of Bosnia-Herzegovina with only the Muslim community, or denying the national identities of the Serbs and Croats of this Republic. Thus, Salim Ćerić denounced the hegemonic intentions lurking behind the name “Bosnian”:

By suggesting the idea of a Bosnian nationality, a relative minority, the Muslims, seeks to impose itself as the soundest fundamental historical factor of the state subjectivity [državnost] of the SRBiH [Socialist Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina]… The idea of a Bosnian nationality (of Muslims) creates confusion in interethnic relations in Bosnia-Herzegovina… [This idea] gives rise to doubts, for the Serbs and Croats, as to the Muslim perception of the long-term national commitments of the Serbs and the Croats of the SRBiH.24

Thus, recognition of the Muslim nation did not end the complexity of the national question in Bosnia-Herzegovina; it remained the only Yugoslav republic to comprise several constituent nations, with none of them eponymous. Moreover, the Muslims were the only constituent nation not to have their own federal unit. Hence the definition of the ties between the Muslim national identity and the political subjectivity of Bosnia-Herzegovina was also complex, giving rise to recurring tensions between the SKBiH’s leaders and Muslim intellectuals. Some intellectuals sought to give the Muslim nation its own cultural attributes, such as its own language or literature, and thus called for the creation of national institutions responsible for promoting these attributes. On a linguistic level, the unity of the Serbo-Croatian language was challenged in the 1960s by the recognition of two dialects: eastern (Serb) and western (Croat), and by the 1967 publication, as part of the “Croat Spring,” of a Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Standard Language. The SKBiH’s leaders took the risk of a splitting of the Serbo-Croatian language very seriously, viewing it as a threat to the very existence of Bosnia-Herzegovina. In their view:

A polarization between dialects would definitely lead to the disintegration of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian culture, and teaching—in the case of a substantial enforcement of the distinction between dialects—would have to be separated… We would therefore have the kind of “national” schools that would closely resemble the confessional teaching of the nineteenth century. Ultimately, such a policy would lead to the disintegration and the negation of the sovereignty of the Socialist Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina.25

The SKBiH leaders were therefore opposed to the Muslim intellectuals such as literature professor Alija Isaković, who highlighted the specific features of the language of Bosnia-Herzegovina—beginning with its numerous Turkisms—and called for recognition of a Bosnian dialect of Serbo-Croatian. The SKBiH merely promoted equality between the two Serbo-Croatian dialects and the greatest tolerance for their use in Bosnia-Herzegovina. However, it referred to a “standard pronunciation” (standardnojezički izraz) specific to Bosnia-Herzegovina, to be defined more precisely by the Institute for Language and Literature inaugurated in Sarajevo in 1972.

The language issue showed how the affirmation of a specific national identity for the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina did not necessarily strengthen this republic as a distinct federal unit. Similar tensions and dilemmas arose with regard to the recognition of a specific form of Bosnian literature or Muslim literature—not to be confused with each other. In the 1960s and 1970s, writers, literature professors, or historians such as Alija Isaković, Muhsin Rizvić, Midhat Begić, and Hazim Šabanović contributed to a rediscovery of Muslim writers from the Ottoman period, the Austro-Hungarian period, and the interwar years. Yet at the same time, philosopher Muhamed Filipović was accused of “Muslim nationalism” for mentioning a “Bosnian spirit” (bosanski duh) common to all writers from Bosnia-Herzegovina, and for having criticized the fact that some of these writers were incorporated into Serb or Croat literature.26 As for plans to write a history of the literature of the peoples of Bosnia-Herzegovina, they fell through due to tensions that broke out between contributors of different nationalities. Similar difficulties arose in the field of history. While the historiography of the Muslim nation was developing rapidly, the historiography of Bosnia-Herzegovina was stifled by national dissensions. Plans were made in 1968 to write a history of the nations of Bosnia-Herzegovina, but this project never got off the ground.

Struggling to define the contours of a specific language, literature, and history, the promoters of the Muslim national identity were also deprived of national institutions to accomplish their project. Whereas the Serbs could rely on the Serb Academy of Sciences and Arts or the cultural association Matica srpska, and the Croats had the cultural association Matica hrvatska, the Provincial Museum or the Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia-Herzegovina were not institutions intended for the Muslim community alone. Unsurprisingly, some intellectuals called for the creation of Muslim national institutions. For example, Salim Ćerić wrote in 1971 that “the Muslim nation is the only nation in the SFRJ not to have this kind of institution, even while it is in its formational period,” and called for the creation of a Matica muslimanska in charge of promoting the Muslim cultural heritage, writing the history of the Muslim nation and revising the content of schoolbooks.27 Yet Ćerić, too, was denounced as a “Muslim nationalist,” and the leaders of the SKBiH once again raised fears of Bosnia-Herzegovina breaking apart. For instance, Branko Mikulić stated that “the idea of national institutions … cannot be achieved without civil war.”28

The fear of a violent breakup of Bosnia-Herzegovina that was sometimes perceptible in the words of Muslim politicians and intellectuals explains their ambiguous attitude towards the Yugoslav idea. On the one hand, they rejected Yugoslavism as they had Bosnism, viewing it as a negation of the specific national identity of each constituent nation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. To promote the Muslim national identity, they had to end the national identification of Muslims as “undetermined Yugoslavs,” which had been typical of the first two decades after the war. On the other hand, only the Yugoslav federal framework protected Bosnia-Herzegovina from the claims of Serb and Croat nationalists, and allowed the Muslim elites to manage the paradoxes and ambiguities of the Muslim national identity. These elites thus showed a strong attachment to the Yugoslav state and to the idea of a socialist community of the Yugoslav nations. According to Atif Purivatra:

We cannot speak of Yugoslavism in the sense of a sentiment of belonging to a Yugoslav nation, because no such nation exists. However, the sentiment of Yugoslavism is a specific sentiment of belonging to a larger social community that has developed due to the existence of the socialist community of the Yugoslav nations, due to socioeconomic ties and socialist policies that are bringing our nations together and uniting them, ever more soundly and profoundly, and reducing the social functions of the nation.29

Even as they were developing the new Muslim national identity, Muslim politicians and intellectuals thus reaffirmed their allegiance to the plurinational state of communist Yugoslavia. Admittedly, certain intellectuals—such as Muhamed Filipović, Alija Isaković, and Salim Ćerić—were accused of “Muslim nationalism,” but in the 1970s, this accusation was unfounded. These intellectuals never challenged the legitimacy of Yugoslavia and did not aspire to create an independent Bosnia-Herzegovina or a nation-state specifically for Bosnian Muslims. The Muslim nation was, we might say, a nation without nationalism. The SKBiH’s leaders were not mistaken on this account, and the Muslim intellectuals generally fell out of favor for only a short period of time.

Nevertheless, the tensions between the SKBiH’s leaders and certain Muslim intellectuals showed that the promotion of the Muslim national identity brought with it several conflicts among the new Muslim elites. While most intellectuals supported the “national affirmation” process, a few were more reserved. The writer Meša Selimović continued to state that he was a Serb, and the writers Skender Kulenović and Mak Dizdar still declared themselves to be Croats. The historian Enver Redžić, for his part, criticized the adoption of a national name with a religious origin in a context of socialist secularization, stating: “even if the role of Islam in the process of forming the Bosnian Muslim ethnic community is undeniable, this community itself is not ethnically Muslim, but Bosnian.”30 At the same time, the promotion of the Muslim national identity favored closer ties between the newer post-1945 elites and some representatives of the interwar intellectual elite. The best example of the role played by certain Muslim intellectuals trained before the Second World War is Muhamed Hadžijahić. As a young Croat nationalist, he had worked for the NDH’s propaganda services during the war. In the 1960s, he was the secretary of the Commission for the History of the Peoples of Bosnia-Herzegovina, within the Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia-Herzegovina. He was also the main contributor to a 1970 report for the Central Committee of the SKBiH, about the attitude of the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina toward the issue of national determination (communist intellectuals Atif Purivatra and Mustafa Imamović also contributed to this report).31 Lastly, he was one of the proponents of enriching the new Muslim national identity with markers of cultural identity produced in earlier periods. Other links between the intellectual elites of the interwar and communist periods could be found in the Oriental Institute, which opened its doors in 1950. The historian Hazim Šabanović, for example, was a former student at the Higher Islamic School for Theology and Shari‘a Law. Lastly, the literature professor Muhsin Rizvić, who played a crucial role in the promotion of Bosnian Muslim literature, was a former member of the Young Muslim movement.

To complete this overview of the pluralism within the Muslim intellectual elites, we must also look at the situation of Muslim political emigration. In the first decade after the war, Bosnian Muslim refugees in the West or the Middle East were indistinguishable from Croat political émigrés, whether Ustashas or democrats. However, from the mid-1950s, some of these Muslim refugees denounced attempts to force them to convert to Catholicism, then stopped identifying as Croats. At the initiative of Adil Zulfikarpašić, a former Partisan and communist minister who had emigrated to Switzerland, the Liberal-Democratic Alliance of Bosniaks-Muslims (Liberalno-demokratski savez Bošnjaka-Muslimana) was founded in 1963. This alliance gathered Muslims who had studied abroad during the war, alongside former imams of the 13th SS Division and former Young Muslims. It came out in favor of the national name “Bosniak,” seeking to break with the Serb and Croat national identities because:

For us Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bosnism [bošnjaštvo] is more than just a regional sentiment, more than a geographic concept, more than a cultural and historical particularity, even though it encompasses all these things. Bosnism is, for us, our true and our only national identification.32

Yet the definition of Bosnism was unclear in the Muslim political emigration as well. Sometimes the term referred to all the inhabitants of Bosnia-Herzegovina and sometimes just to the Bosnian Muslims. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Muslim elites in Bosnia-Herzegovina and the representatives of Muslim political emigration opted for different national names—a divergence whose consequences would become apparent in the early 1990s. Meanwhile, they all agreed that only the Yugoslav federal framework could protect Bosnia-Herzegovina from Serb and Croat nationalist claims. Thus, Adil Zulfikarpašić joined the Democratic Alternative (Demokratska alternativa), an organization created in 1963 by Yugoslav political émigrés with a democratic orientation. While this organization recognized the right to self-determination of each South Slavic nation, it still stated that “a common state of the Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians, and Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina is necessary to preserve the political, ethnographic [sic] and geographic integrity of each nation of Yugoslavia,” and thus called for the creation of a new democratic Yugoslavia.33

In the end, a study of the national affirmation process reveals that the recognition of the Muslim nation in the 1960s and 1970s was not simply granted by Tito or by the communist leaders of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Instead, it was also brought about by the efforts of many Muslim intellectuals, and was not devoid of dilemmas and conflicts. Likewise, the Muslim national identity promoted by Muslim politicians and intellectuals was not a pure creation of the communist period, but also made use of the markers of cultural identity produced during the Austro-Hungarian and interwar periods. The choice of “Muslim” as the national name was driven by a desire to maintain a balance between the three constituent nations of Bosnia-Herzegovina, while also rooted in the common usage of this religious name since the beginning of the twentieth century. From this standpoint, using the national name “Muslim” to refer to the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina was a lingering trace of their former status as a non-sovereign and protected religious minority. Lastly, the new Muslim political and intellectual elites’ attachment to communist Yugoslavia was in part an extension of the traditional Muslim elites’ allegiance to the prevailing central power. For communist leaders and intellectuals as well, the existence of the plurinational Yugoslav state was a sine qua non condition for the physical and political existence of the Muslim community. Nevertheless, during the 1960s and 1970s, the new Muslim elites of the communist modernization were successful where the Muslim intelligentsia of the Austro-Hungarian and interwar periods had failed. They were able to make the specific cultural identity of Bosnian Muslims fit into a political environment dominated by national categories, finally nationalizing the Bosnian Muslim population—as proven by vast numbers of people who declared “Muslim” to be their national identity during the 1971 census.

During the communist period, the activity of Islamic religious institutions was affected by changes in the Yugoslav state’s antireligious policy, transformations in Bosnian society, and the recognition of the Muslim nation. In the late 1950s, the decline of the Islamic Religious Community appeared irreversible. Following the nationalization of the waqfs, and despite an annual state subsidy, the Islamic religious institutions were in dire financial straits. Religious personnel were increasingly few in number and had a low level of education. The Gazi Husrev-beg Madrasa in Sarajevo, the only madrasa still open, graduated only a dozen students a year, and most of these graduates did not opt for a religious career. Lastly, the only Islamic religious publications were Glasnik (“The Messenger”), which dealt mainly with the religious institutions’ internal affairs, and Takvim (“Almanac”), which informed the faithful of the times for the five daily prayers and the dates of the main religious holidays. After the communist authorities had evicted it from the public sphere, the Islamic Religious Community withdrew into its mosques, where it continued to perform the main religious rituals. However, changes started to occur in the 1950s: religious lessons were reauthorized in places of worship in 1953, Sulejman Kemura was elected as Reis-ul-ulema in 1957, a new internal constitution simplified the functioning of religious institutions in 1959,34 and from the late 1950s, the khutbas (Friday sermons) were given in Serbo-Croatian, not in Arabic.

The narrower scope of activities for the Islamic Religious Community coincided with a rapid decline in religious practice. However, this secularization of the Muslim community did not affect all social classes equally. In research carried out in the early 1960s in Herzegovina, sociologist Esad Ćimić showed that religious practice was higher in the countryside than in towns, and especially low for people involved in the communist modernization. Yet Ćimić’s main finding was that a decline in religious practice did not mean that religion was simply disappearing; for example, he observed high participation in the main religious holidays:

During the religious holidays, more than ninety private houses in the region [Herzegovina] are “transformed” into places of worship, to allow as many people as possible to perform the main religious rites. In 1963, there were ninety-three religious events, namely three major gatherings that brought together 13,000 believers, and ninety mevluds [ceremonies in honor of the Prophet] involving around 70,000 believers (i.e. on average 700 to 800 believers each).35

Among the reasons behind this persistent religiosity, Ćimić cited the identification between nationality and religion, especially for the Muslims, who “have a consciousness in which nationality and religion are often intermingled and complementary (and more clearly so than for others).”36 Anthropologist William Lockwood and historian Robert Donia, who had done fieldwork in Bosnia-Herzegovina in the 1960s and 1970s, also noted: “For most Bosnian Muslims, the significance of religious adherence as a symbol of ethnicity outweighs the importance of religious belief and dogma.”37 The Muslims thus closely associated their national and religious identity, even while the communist authorities hoped that recognizing the Muslim nation would facilitate their secularization.

This question of the relationship between national identity and religious identity was also on the minds of members of the Islamic Religious Community. Initially, the ‘ulama’ were reluctant to use the term “Muslim” in a national sense. In the Takvim for 1965, Kasim Dobrača noted that the term “Muslim” is a religious concept, and he therefore deplored that “an ethnic meaning should be given to the concept ‘Muslim’, and that this term be used to designate an individual who, for example, belongs to the Muslim group only because of his origins, but who denies in theory and in practice his belonging to Islam.”38 Faced with this hesitancy on the part of some ‘ulama’, the national name “Muslim” found a tireless defender in Husein Đozo. A 1939 graduate of al-Azhar University, sentenced to five years in prison in 1945 for his role in the 13th SS Division, then reincorporated into the Islamic religious institutions in the late 1950s, Đozo became President of the Association of ‘Ulama’ of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1964. As such, he had great influence within the Islamic religious institutions. In his view, the Bosnian Muslims gaining the status of constituent nation of the Yugoslav federation was a major historical turning point, because it removed the “Turkish burden” that weighed on them:

For the first time in their history, the Muslims are standing upright on their land. They have finally freed themselves from accusations of being foreigners or the remnants of the foreign occupant, which certain [Serb] nationalist forces wanted to apply to them, and which has weighed on them heavily.39

For Đozo, the recognition of the Muslim nation freed the Muslims of a deep-rooted sentiment of insecurity and inferiority, and made them fully fledged members of the community of Yugoslav nations. Then, turning to the connection between national identity and religious identity, between Musliman with a capital “M” or a lower-case “m,” he noted:

Beginning now, the concept of Muslim no longer designates merely a member of the Islamic religion, but also a member of the Muslim nation, whether this member is a believer or not… It would appear that Islam loses out here. It seems indisputable that, in this case, the word “Muslim” is formally alienated and removed as far as possible from Islam. And yet, this is not the case. I would say that it is more a return than an alienation. The lower-case “m” does not lose out, it wins. The capital “M” strengthens and consolidates it even more.40

To understand fully Đozo’s stances on the issue of Muslim national identity, we must view them within his broader vision of the relationship between Islam and the socialist society. Đozo was in fact a typical representative of Islamic reformism, influenced by the thought of Muhammad Abduh, Rashid Rida, and Mahmud Shaltut. It was he who, in the 1960s, successfully imposed Islamic reformism as the dominant current of thought in the Islamic Religious Community. Đozo tirelessly advocated a renewal in Islamic thought that can be summarized in two basic demands: “to purify Islam of the various mistakes and erroneous conceptions that have been introduced over a long period, and to revive ijtihad and the elaboration of new Islamic conceptions.”41 Moreover, throughout the 1960s and 1970s, he spent a considerable amount of time answering readers’ questions in the columns of the religious press, and through his answers (fatwas), he contributed to a subtle transformation in how Islam was conceived and practiced in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Đozo also wanted to break with the narrow or mystic conceptions of religious life, and encouraged believers to become more involved in socialist society:

It is of the greatest importance [to know] how the Muslim as a member of the Islamic Community, and thus as a believer, positions and integrates himself into the new socialist reality… Each member of the Islamic Community is also a citizen of the socialist community. As a Muslim, he does not have the right to be closed [withdrawn], he must be completely open to society and completely integrated and involved in the processes of this society.42

In opposition to the ‘ulama’ and other religious Muslims who focused only on performing religious rituals, Đozo advocated active involvement in the new social and political reality. In his view:

Muslims are deeply aware that socialist society offers them the best guaranties for their existence, development and wellbeing. This society has enabled them to find themselves, to find their place and to free themselves of certain burdens of the past.43

These words probably concealed a certain degree of hypocrisy. However, Đozo’s allegiance to communist Yugoslavia was similar to that of the new political and intellectual elites linked with communist modernization, and fit with the tradition of allegiance to the central power that went back to the Austro-Hungarian period.

In Đozo’s view, the Islamic Religious Community had to accept the socialist reality in order to be able to revive religious life and re-enter the public sphere. The recognition of the Muslim nation enabled the Muslims “to go from a narrow form of our [religious] existence and our evolution to a broader form of our national and social existence.”44 In re-entering the public sphere, the Islamic Religious Community would also facilitate a redefinition of the relationship between the ‘ilmiyya and the new Muslim intelligentsia. Aware that “at present, the new progressive forces, the forces of the capital ‘M’ hold the advantage,” Đozo called for a convergence between the ‘ilmiyya and the intelligentsia:

There are real possibilities for that. The forces of the [religious] infrastructure are increasingly adapting to the contemporary world, while the forces of the [national] superstructure are taking more and more account of their historical foundation. The objective is thus the same. Perhaps the ways and means of achieving this objective are different, but that should not be troublesome.45

In this prospective relationship, the ‘ilmiyya would have the possibility of relying on its own institutions, whereas the Muslim intelligentsia had none. Đozo thus encouraged Muslim intellectuals to use the Islamic Religious Community as the proxy, or substitute, for a national institution. Hence his confidence in the fact that adopting “Muslim” as the national name would ultimately benefit the Islamic religious institutions and Islam as a whole. According to Đozo, “the lower-case ‘m’ forms the infrastructure for the capital ‘M’, without which it would be nothing more than an empty word, a formula with no content.”46 Despite the devastating effects of the communist modernization and secularization, Đozo thus looked optimistically towards the future of Islam in Yugoslavia. Then, going beyond the Yugoslav framework, he extended his hopes to all of Europe:

The Muslims in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia represent the largest autochthonous Islamic community in Europe. In a way, we could say that this community acts as a matrix for the other Islamic groups (džemats) that have recently appeared in some European countries. From this standpoint, the Islamic Community in Yugoslavia carries a very great responsibility.47

Beginning in the 1960s, the Islamic Religious Community therefore experienced a clear revival in its activity and visibility. In some respects, this renewal of Islamic religious institutions was reminiscent of that of the Orthodox and Catholic Churches at the same period, and can be attributed to factors such as the liberalization of the communist regime, a rekindling of national tensions and demands, or simply the higher standard of living of religious followers. The building of many places of worship in Bosnia-Herzegovina was also made possible by the financial contributions of the diaspora, and in some places, became a veritable competition between religious communities. The number of mosques and prayer rooms rose from 817 in 1955 to 1,661 twenty years later. At the same time, the Islamic religious community experienced considerable growth in its schools. The number of children attending religious classes climbed from 11,500 in 1957 to 115,000 in 1977, while the number of students graduating from the Gazi Husrev-beg Madrasa rose from eleven to forty-three over the same period, and a Faculty of Islamic Theology opened in Sarajevo in 1977 to train the future cadres of the Islamic Community. In Kosovo, the Alauddin Madrasa opened in 1962, and had 196 students in 1975. The Islamic religious press also grew substantially, under Husein Đozo’s decisive leadership.

In 1968, along with printing the hours of prayer, the Takvim began publishing texts about the Islamic faith and the political and cultural history of Bosnian Muslims. Its circulation at the time stood at around 50,000. Besides, the Association of ‘Ulama’ of Bosnia-Herzegovina launched a bimonthly magazine in 1970. Called Preporod (“Rebirth”), its circulation quickly grew to 30,000. To serve on the staff of Preporod, Đozo brought in young clerics recently graduated from the madrasa and—as we shall see later on—former members of the Young Muslim movement. Lastly, the 1970s also saw a revival of the tarikats, which had been banned in 1952, with a Tarikat Centre (tarikatski centar) opening in 1977 to coordinate their activities with those of the Islamic Community.

This renewed activity for the Islamic religious institutions coincided with new visibility, as the Islamic Religious Community gradually took on the status of a proxy national institution. In 1969, a new internal Constitution changed the community’s official name from Islamic Religious Community to the Islamic Community (Islamska zajednica), thus illustrating its desire to broaden the scope of its action beyond merely performing religious rituals. This function as a proxy national institution became particularly apparent during the 1971 census. Preporod relayed the stance of the League of Communists on the national name “Muslim,” and the Association of ‘Ulama’ of Bosnia-Herzegovina even organized seminars to mobilize the imams in favor of this name. A certain convergence of interests thus arose between the leaders of the Islamic Community and the intellectuals involved in promoting the Muslim national identity, notably Atif Purivatra. This rapprochement between the Islamic Community and a portion of the Muslim intelligentsia continued throughout the 1970s, and intellectuals such as historians Muhamed Hadžijahić, Hazim Šabanović, and Enes Pelidija wrote for the religious press during this period. However, the best example of circulation between the academic sphere and the Islamic Community was Hamdija Ćemerlić. Professor of Law at the Higher Islamic School for Theology and Shari‘a Law before the war and a member of the ZAVNOBiH in 1943, Ćemerlić was elected rector of the University of Sarajevo in the 1960s and became a member of the Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia-Herzegovina. After his retirement, he was elected president of the Islamic Community’s vrhovni sabor (supreme assembly) in 1976. A year later, he became the first dean of the Faculty of Islamic Theology. Ćemerlić was therefore one of the main intermediaries between the communist authorities, the Muslim lay intelligentsia, and the Islamic religious institutions.

The national role of the Islamic religious institutions in Bosnia-Herzegovina was, in many respects, similar to the role of the Serb Orthodox Church or the Catholic Church during the same period. However, the Islamic Community’s situation was unique in two regards. Firstly, it was not competing against secular national institutions equivalent to the Serb Academy of Sciences and Arts (for the Serbs) or the association Matica hrvatska (for the Croats), and was thus in a favorable position to take on the role of proxy national institution. Secondly, the renewal of Islamic religious institutions came with a revival of exchanges with the Muslim world. The number of Yugoslav pilgrims to Mecca climbed from sixty-five in 1955 to 1,048 in 1975, and 1,620 in 1990. In 1962, for the first time since the war, the Islamic Community sent five students to al-Azhar University. Twenty-eight years later, it counted 218 graduates of the Gazi Husrev-beg and Alauddin Madrasas in universities in the Muslim world, including 109 in Egypt, forty-four in Saudi Arabia, twenty in Jordan, and fifteen in Turkey. Over the same period, exchanges of delegations with the Muslim world grew in number, and the financial support of certain Muslim states enabled the Faculty of Islamic Theology to open in 1977, along with the construction of the monumental Zagreb Mosque in 1987. As part of Yugoslavia’s policy of non-alignment, the leaders of the Islamic Community were even involved in welcoming the official delegations of certain Muslim states, thus playing a role in Yugoslav foreign policy that had no equivalent for the Orthodox or Catholic Churches. Yet the relationship between the Islamic Community and the Yugoslav authorities was not devoid of tensions. For example, Husein Đozo was reprimanded on several occasions in the official press, which described his views on the Arab-Israeli conflict as anti-Semitic. Beginning in this period, the communist authorities became concerned that “some Muslim clerics tend to overestimate the importance of the religious factor in the Muslim national identity, asserting that national and religious identity are one and the same.”48 However, until the end of the 1970s, the Islamic Community enjoyed relatively wide leeway, which Đozo used to rehabilitate some of the men who had been excluded from Islamic religious life in the 1940s.

Harshly repressed during the post-war period, the members of the pan-Islamist movement Young Muslims (Mladi Muslimani) ceased all organized activity until the 1960s. Admittedly, its members who had been exiled abroad contributed to newspapers such as Der gerade Weg (“The Straight Path,” published in Vienna) and Bosanski pogledi (“Bosnian Viewpoints,” published in Zurich), and took part in organizing the first Islamic religious associations in Austria and Germany, but those who remained in Bosnia-Herzegovina had to make do with informal, discreet contacts with one another. Beginning in the mid-1960s, however, the changes within the Islamic Community opened up a space of liberty that some Young Muslims quickly took advantage of. Their involvement in Islamic religious institutions took on two main forms.

Firstly, with Đozo’s support, they published articles in Takvim and Preporod under pseudonyms. These articles usually dealt with purely religious themes, but could also address social issues such as moral “corruption” or the “backwardness” of Muslim countries. Sometimes, their articles took on an overtly political dimension. In the mid-1960s, the former Young Muslims could thus once again present their conception of Islam to a wide audience. At the same time, they took part in discussion forums organized by Đozo. Beginning in 1966, a weekly forum was held in the Emperor’s Mosque (careva džamija) in Sarajevo, aimed primarily at young people, and involving various outside speakers. After a hiatus between 1972 and 1978, this forum resumed in the tanners’ prayer room (tabački mesdžid), in the Baščaršija district. One of its leaders, young imam Hasan Čengić, spoke about his worries about moral corruption—symbolized by unisex clothing, discotheques and the “sexual revolution”—and called on young believers to show their Islamic faith through their personal ethics and their clothing. In addition, he asked them to recreate spaces for Islamic socialization within the socialist society:

Join or form an Islamic džemat with boys and girls of your age, and instead of meeting with your friends in cafés and discotheques, meet them in mektebs, mosques, houses, mahalas [traditional neighborhoods], schools and during open-air excursions.49

For the former Young Muslims, this discussion forum was an opportunity to come into contact with the students of the madrasa and with young non-religious intellectuals who were interested in Islam and to make them aware of the topics dear to the Young Muslims themselves, such as the need to re-Islamicize the Muslims or the primacy of pan-Islamic solidarity.

During the 1960s, a pan-Islamist current thus took shape again within the Islamic Community. This current counted a few hundred members, from two different generations with very distinct characteristics. The older Young Muslims were often from families of urban notables, and had been trained in the high schools of Bosnia-Herzegovina and the universities of Zagreb or Belgrade. The new generation of pan-Islamist sympathizers had more rural, modest origins. Deprived of its former prestige, the Gazi Husrev-beg Madrasa drew students for whom a career as a cleric represented either a family tradition, a means of social advancement, or both, as in the case of the sons of rural imams. By acquiring religious knowledge that their fathers lacked, while attending in parallel the faculties of philology or political science of Sarajevo, these students were educated both as an ‘alim and as a secular intellectual. They therefore went through an identity and moral crisis similar to that which the Young Muslims had experienced in the late 1930s. Lastly, to complete this portrait of the Bosnian pan-Islamist current, we must mention the ties that it built with certain Arab students who belonged to the Muslim Brotherhood. These students notably helped disseminate the writings of Islamist authors such as Hassan al-Banna, Muhammad Iqbal, Abul A’la Maududi, and Sayyd Qutb. Some of them, such as the Sudanese Fatih al-Hassanein, would play a crucial role in the 1990s in fostering ties between Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Muslim world.

Among the texts written by members of the pan-Islamist current at that time, the most political, by far, was the Islamic Declaration written by Alija Izetbegović. He was a Young Muslim who had been sentenced to three years in prison in 1946, later graduating from the law school of Sarajevo and working as a jurist in various public companies. The Islamic Declaration, completed in 1970 and parts of which were published in Takvim in 1972, resembles an informal manifesto for the Bosnian pan-Islamist current. Its preamble notes the “backwardness” of Muslim countries, as reflected in their poverty, low level of education, and subservience to Western powers. Rejecting equally the conservative ‘ulama’ and the Sufi sheikhs who “pull Islam back to the past,” and the modernist intellectuals who “prepare a future [for Islam] which is not its own,”50 Izetbegović then reserves his harshest criticism for the secular regimes of the Muslim world, from Kemalist Turkey to the Indonesian philosophy of pancasila, along with the Ba’athist regimes of the Arab world. In his view, their authoritarian secularization policies led to failure, as shown by the case of Turkey: “As an Islamic country, Turkey dominated the world,” whereas “Turkey as a plagiarism of Europe is a third-rate country.”51

Alija Izetbegović called for the establishment of a new “Islamic order” throughout the whole Muslim world. But he struggled to define the contours of this new order. Thus, he proclaimed that “there is no peace or coexistence between the Islamic faith and non-Islamic social and political institutions,”52 but just after, called for studying the experiences of the United States, the USSR, and Japan without preconceived judgments, ultimately describing Islam as a “median thought” in a world divided into two blocs. When attempting to define more clearly the Islamic order that he was advocating, Izetbegović merely gave general considerations about the equality and fraternity of believers, the republican principle, the necessary restrictions to private property and freedom of the press, as well as the importance of education, moral, and family values. Unable to give precise political content to his Islamic project, Izetbegović emphasized its moral dimensions, eventually defining the Islamic order in these tautological terms:

To the question, “What is a Muslim society?” our answer is a community made up of Muslims, and we consider that this answer says it all, or nearly so. The meaning of this definition is that there is no institutional, social or legal system that can exist separately from the people who are its actors, of which we could say, “This is an Islamic system.” No system is Islamic or non-Islamic per se. It is only so based on the people who make it.53

Evasive as to the nature of the Islamic order, Izetbegović was hardly more precise in describing the paths that would lead to the establishment of this new order. In his view, “the Islamic renaissance cannot begin without a religious revolution, but it cannot continue and be complete without a political revolution.”54 Establishing the Islamic order would thus involve, first and foremost, the re-Islamization of Muslim societies, from the bottom up. To this end, Izetbegović called for a new, re-Islamicized intelligentsia that would be able to mobilize the Muslim masses.