In 1990, nationalist parties won the elections in all the Yugoslav republics, making the disintegration of Yugoslavia irreversible. On the one hand, Slovenia and Croatia quickly moved towards independence. Slovenia organized its independence referendum on December 23, 1990, followed by Croatia on May 19, 1991. Both republics proclaimed their independence on June 25, 1991. On the other hand, Serbia and Montenegro took control of the Yugoslav federal institutions, notably taking over the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA). The European Community, which intended to demonstrate its ability to handle the Yugoslav crisis on its own, convened an international conference on Yugoslavia in August 1991, declared the Yugoslav federation to be in the process of dissolving in December 1991, and recognized the independence of Slovenia and Croatia a month later. In the meantime, Macedonia and Bosnia-Herzegovina were more hesitant as to which stance they should adopt towards the disintegration of the Yugoslav federation. However, following the Slovenian and Croatian proclamations of independence, as well as the changing stance of the European Community, these two republics also began to move towards independence. Macedonia organized a referendum on September 7, 1991, and Bosnia-Herzegovina asked for international recognition as an independent state on December 20, 1991. At the behest of European authorities, it organized its own referendum on March 1, 1992 (64.3 percent voter turnout, 99.4 percent in favor of independence), and proclaimed its independence two days later. Then, Serbia and Montenegro acknowledged the disappearance of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and created a new, rump Yugoslav state on April 27, 1992: the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Savezna republika Jugoslavija—SRJ).

Apart from Bosnia-Herzegovina, which still had three constituent nations, the new states formed out of the Yugoslav federation defined themselves as nation-states embodying the sovereignty of their eponymous nation and considerably reduced the rights of their national minorities. In Slovenia, where 87.6 percent of the population declared itself to be of Slovene nationality, this triumph of the nation-state principle was relatively painless. However, this was not the case in the rest of the Yugoslav space, where state borders did not coincide with ethnic boundaries (see Map VII). The new independent states had large minority populations of Serbs (31.4 percent in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 12.2 percent in Croatia), Croats (17.3 percent in Bosnia-Herzegovina), and Albanians (17.2 percent in Serbia and 21.0 percent in Macedonia). The disappearance of the plurinational state of Yugoslavia thus had the logical consequence of awakening nationalist projects that aspired to bring together all the members of one nation within a single nation-state, and challenged existing borders. These projects, often described as “Great Serbia,” “Great Croatia,” or “Great Albania,” nevertheless took more complex forms than these terms would suggest. Initially, Serb nationalists claimed to be defenders of the Yugoslav federation rather than promoters of a Great Serb nation-state, to mobilize the strong Yugoslav sentiments of the Serb populations, while also fitting into the categories of international law. More generally, the protagonists of the Yugoslav crisis could defend the territorial integrity of the state or, alternatively, call for the people’s self-determination, depending on the place and circumstances. For example, Serb nationalists defended the right to self-determination of the Serbs of Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina but were opposed to Albanian separatist claims that threatened the territorial integrity of Serbia. Eventually, the various nationalist players formally accepted the principle of intangibility of borders supported by the European Community. Thus, they did not openly attach new territories to the nascent nation-state, but supported instead the formation of self-proclaimed quasi-states within the borders of neighboring states. For example, Serb nationalists created “autonomous Serb regions” in Croatia in summer 1990, grouping these together into a “Serb Republic of Krajina” on December 19, 1991. They repeated the same scenario in Bosnia-Herzegovina, with the creation of “autonomous Serb regions” in autumn 1991 and the proclamation of a “Serb Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina” on January 9, 1992. In parallel, the Croat nationalists created two “autonomous Croat regions” in Bosnia-Herzegovina in November 1991. Further south, the Albanian nationalists organized a plebiscite on the independence of Kosovo on September 30, 1991, and another on the autonomy of western Macedonia on January 11, 1992. In all these cases, the nationalists aimed to show their domination over certain territories before being able to bring them together into a single nation-state.

In a Yugoslav space characterized by the diversity of its populations, this drive to create homogenous nation-states would inevitably trigger violence. This was particularly true for the Serb nationalists, who were determined to use force to take control of Serb-populated regions in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. As early as spring 1991, the first armed confrontations occurred in Croatia between the Croatian police and Serb militias supported by the Yugoslav Army. After the declarations of independence on June 25, 1991, fighting between the Yugoslav Army and the Territorial Defense of Slovenia lasted only a few days and resulted in the withdrawal of the federal troops. But in Croatia, the conflict that pitted the young Croatian Army against the Yugoslav Army and Serb militias became outright war, as shown by the Yugoslav Army’s siege of the town of Vukovar from August to November 1991. The war in Croatia also saw the first cases of people being forcibly expelled on an ethnic basis—a practice described in the Yugoslav space as “ethnic cleansing” (etničko čišćenje). By the end of 1991, the war in Croatia had killed nearly 11,000 and created 300,000 refugees, and the “Serb Republic of Krajina” controlled around 30 percent of Croatian territory. On January 3, 1992, a UN-negotiated ceasefire allowed for the creation of “protected areas” corresponding to the regions settled by Serb populations in Croatia, and a 12,000-strong United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) was deployed. At that point, the war was interrupted in Croatia, but soon expanded into Bosnia-Herzegovina.

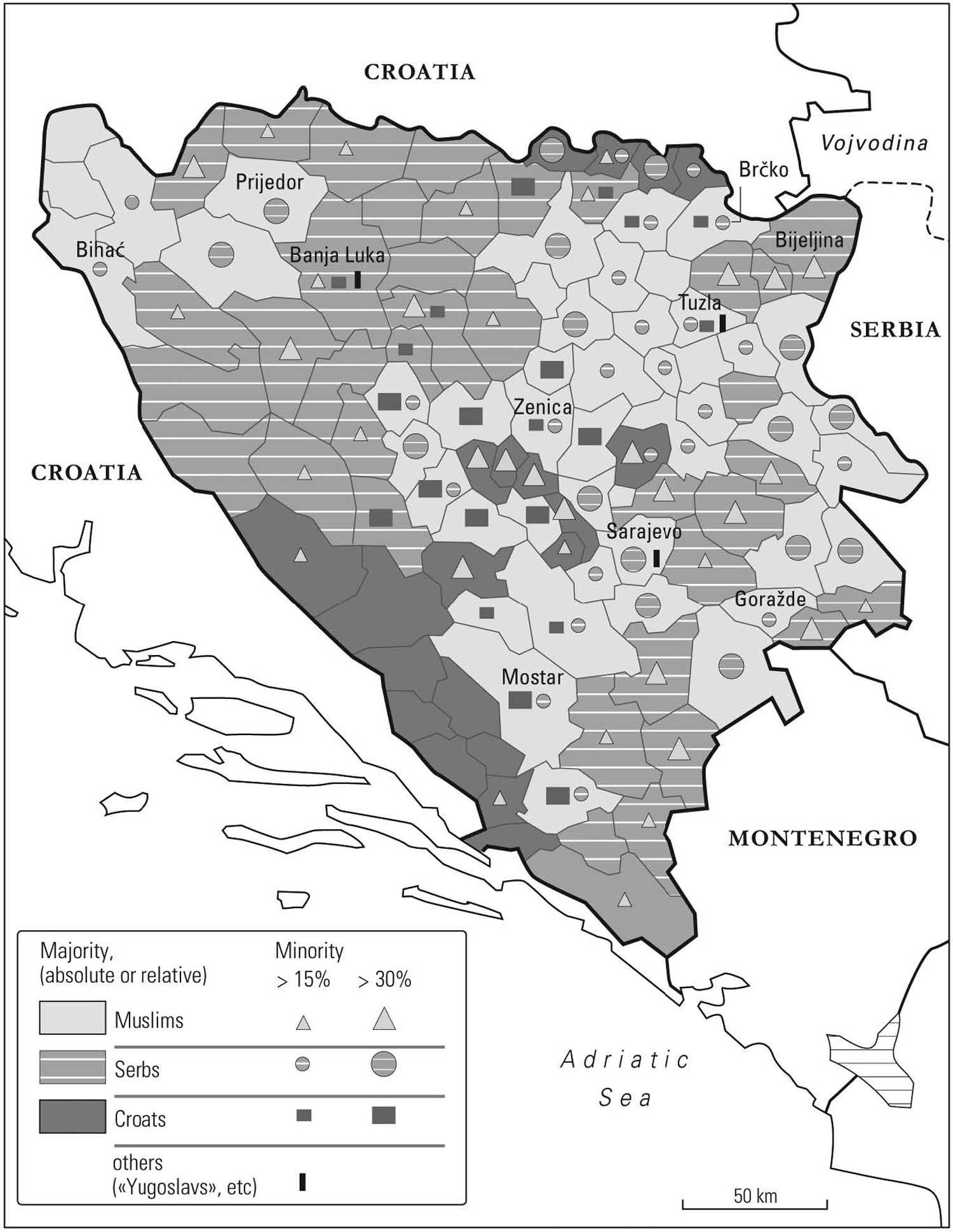

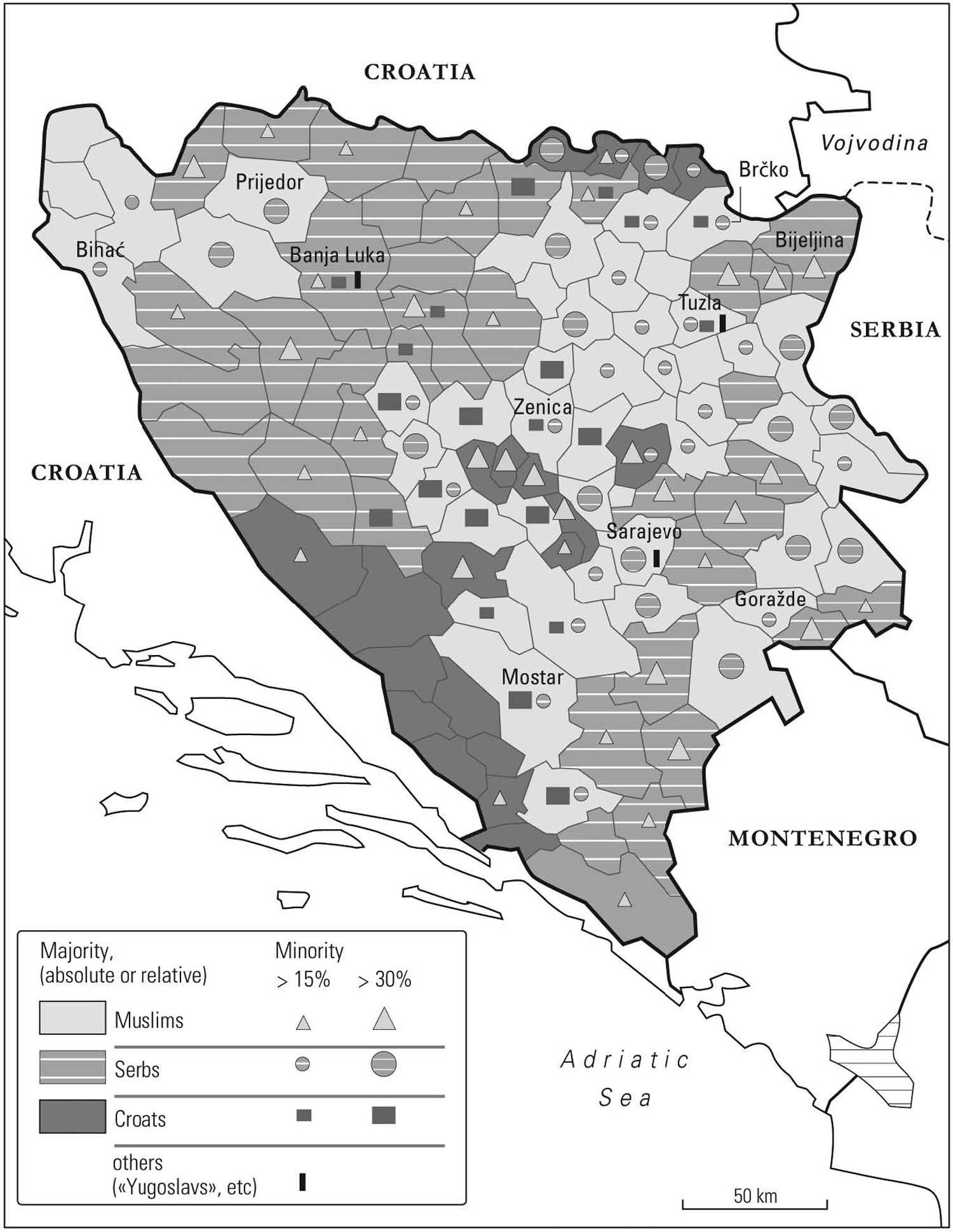

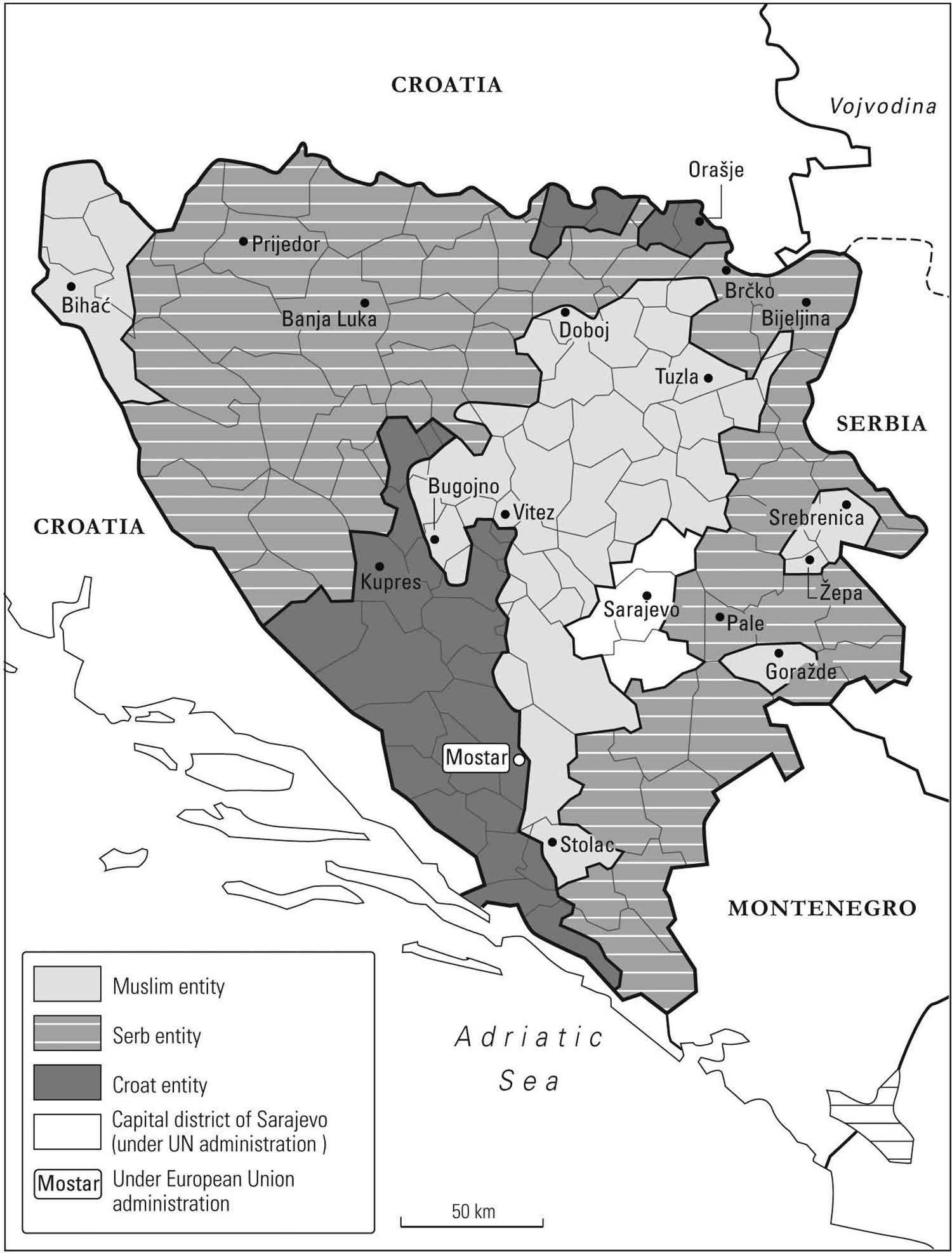

Map VII Ethnic breakdown of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1991.

Wedged between Serbia and Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina’s population in 1991 was comprised of 1,905,829 Muslims (43.7 percent of the total), 1,369,258 Serbs (31.4 percent), 755,895 Croats (17.3 percent), 239,845 Yugoslavs (5.5 percent), and 93,747 from other national categories (2.1 percent). The country was thus at the center of the territorial claims awakened by the collapse of the Yugoslav federation. On March 25, 1991, Serbia’s President Slobodan Milošević and Croatia’s President Franjo Tuđman met in Karađorđevo, on the Croatia–Serbia border, and during their meeting, a partition of Bosnia-Herzegovina was mentioned as a possible solution to the territorial dispute between Serbia and Croatia. As with the 1939 Cvetković–Maček Agreement or during the Second World War with the Ustasha and Chetnik projects, the triumph of the nation-state principle in the Yugoslav space threatened the existence of Bosnia-Herzegovina as a distinct territorial entity, and therefore, the political sovereignty and physical security of the Muslim nation. This was the context behind the SDA’s ambiguous, hesitant stance toward the disintegration of the Yugoslav federation.

Indeed, in the weeks following the elections of November 18, 1990, the SDA reaffirmed its attachment to Yugoslavia: in January 1991, a resolution signed by eighty-four Muslim intellectuals close to the SDA stated that “the Muslims consider the existence and development of a democratic and fair Yugoslav community to be an essential condition for their [own] existence and development.”1 One month later, during a meeting in Bihać, Alija Izetbegović reminded his audience that “Yugoslavia is not our love, but it is our interest.”2 Yet in the same period, SDA deputies presented the Bosnian Parliament with a Declaration on the Sovereignty and Indivisibility of Bosnia-Herzegovina that did not even mention the existence of the Yugoslav federation.3 This declaration sparked a confrontation with the Serb Democratic Party (SDS), which considered it denying the existence of Yugoslavia and disputing the Serb nation’s right to live in a single state.

Thus, in contrast with the idea that events forced the SDA to opt for Bosnian independence, the reality is slightly more complex. Faced with the SDS’s hostile reaction, the SDA withdrew its declaration on the sovereignty of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and in the following months, it adopted a more cautious stance on the future of Yugoslavia. In May 1991, Izetbegović joined with Macedonia’s President Kiro Gligorov in supporting the idea of an “asymmetric federation” in which the republics of Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, and Montenegro would have federal ties, while Croatia and Slovenia would have looser ties with the other republics, as in a confederation. However, the independence of Slovenia and Croatia, along with the military escalation in Croatia and the European Community’s evolving stances marked the death knell for the Yugoslav federation. The SDA’s leaders were then faced with a delicate choice: either agree for Bosnia-Herzegovina to remain part of a rump Yugoslavia under Serbia’s domination, or support independence for Bosnia-Herzegovina despite the Bosnian Serb community’s opposition. The moment of truth came in August 1991, when the SDS and the Muslim Bosniak Organization (MBO), a small party that had split from the SDA in September 1990, published a project for an “historic Serbo-Muslim agreement.”4 In this project, the two parties suggested that the Muslim community could support a rump Yugoslav state in exchange for guarantees regarding the territorial integrity of Bosnia-Herzegovina. In so doing, the MBO gave priority to maintaining Bosnian territorial integrity, even if it meant reducing the political sovereignty of the Muslim nation. Yet after some hesitation, the SDA’s leaders rejected this “historic agreement.” Muslimanski glas (“The Muslim Voice”), the SDA’s official newspaper, denounced the idea of a “rump Yugoslavia in which the Serbs would be number one, and the Muslims number two.”5 This decision by the SDA to favor the Muslim nation’s political sovereignty, even to the detriment of Bosnian territorial integrity, shows once more how the party was breaking with the strategies of the pre-1945 Muslim elites, which had renounced any national project of their own in order to better preserve the existence of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Beginning in August 1991, the SDA was leading Bosnia-Herzegovina on the path towards independence, adhering to the schedule laid out by the European Community. On October 15, 1991, just after the international conference on Yugoslavia had started, the SDA and HDZ deputies adopted a memorandum on the sovereignty of Bosnia-Herzegovina, declaring that, “in light of the national composition of its population, Bosnia-Herzegovina will not accept any constitutional solution for the future Yugoslav community that would not include both Serbia and Croatia.”6 This memorandum also received the support of a majority of deputies from the civic parties, which thus broke with their initial support for preserving the Yugoslav federation. Indeed, with war raging in Croatia, the October 15, 1991 memorandum amounted to rejecting any plans for a new Yugoslav federation. Unsurprisingly, this memorandum sparked a new confrontation with the SDS, which called for a referendum for self-determination to be held for each of the three constituent nations of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In the following months, the SDA, the HDZ, and the civic parties supported the request for international recognition sent to the European Community on December 20 1991, i.e., three days before the deadline set by the European authorities. They then organized an independence referendum on March 1, 1992, at the behest of these same European authorities. Politically isolated, the SDS responded by creating several “autonomous Serb regions” between September and November 1991, by organizing a plebiscite on November 10, 1991 about the Serbs of Bosnia-Herzegovina remaining in the Yugoslav federation, and by proclaiming a “Serb Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina” on January 9, 1992. In the “autonomous Serb regions,” the SDS monopolized power and increased intimidation measures against non-Serb populations. On March 1, 1992, the SDS called for a boycott of the independence referendum. Thus, Bosnia-Herzegovina’s march towards independence went hand in hand with an increasingly overt challenge to its territorial integrity and its interethnic balances.

Between December 1990 and April 1992, the future of Yugoslavia was not the sole issue facing the SDA’s leaders. As Bosnia-Herzegovina’s independence grew closer, the SDA also had to clarify its vision for the Bosnian state. In the early months of 1991, it repeatedly expressed its support for a civic definition of this state, one that did not refer to the existence of the three constituent nations. Thus, the declaration proposed to the Bosnian Parliament in February 1991 defined Bosnia-Herzegovina as “the sovereign state, united and indivisible, of all the citizens who live there,” exercising their sovereignty through their representatives or through referendum.7 In this declaration, the existence of the three constituent nations was not even mentioned—a fact that sparked hostility from the SDS. For certain leaders of the SDA, their new-found support for the civic principle was a good way to get rid of the consociational mechanisms embedded in the Bosnian Constitution, and thus to transform Bosnia-Herzegovina discreetly into a state for the Muslim nation. Significantly, the slogan chosen by the SDA to encourage its supporters to declare themselves “Muslim” during the census was “Our rights depend on our numbers.” A year later, Izetbegović himself fueled these ambiguities about the use of a civic definition of Bosnia-Herzegovina, stating that he was prepared to “inscribe in the Constitution a guarantee that Bosnia will not become a Muslim state in the next fifty years.”8

However, as tensions worsened in Bosnia-Herzegovina, emphasis on the civic principle also became a way to oppose any sort of partition along ethnic lines. In August 1991, asked about the partition projects that Milošević and Tuđman had spoken about in Karađorđevo, Izetbegović stated:

We were offered a sort of Muslim state, and we refused it… We clearly replied that we wanted a civic republic in Bosnia-Herzegovina because—let us understand each other clearly—it is the only solution possible. Perhaps we would be ready to accept such a proposal [for partition]—after all, if the Croats and the Serbs have their own nation-states, why not the Muslims? But it is not realistic… A Muslim state in Bosnia-Herzegovina does not appear realistic to me because there is no compact Muslim space, and we would therefore only obtain a reduced Bosnia, with all the problems that this would entail.9

However, in October 1991, the memorandum on the sovereignty of Bosnia-Herzegovina adopted by the Bosnian Parliament made explicit reference to the three constituent nations: this return to a consociational conception of the Bosnian state enabled the SDA to counter the SDS’s criticisms and to win the support of the Croat HDZ, which was in favor of independence for Bosnia-Herzegovina but strongly attached to the consociationalism of Bosnian institutions. Moreover, the HDZ requested that the question asked in the self-determination referendum define Bosnia-Herzegovina as “a state community of three constituent nations, sovereign in their national spaces (cantons).”10 The SDA’s hesitations and ambiguities about the issue of citizenship were partly attributable to the difficult context it faced. But they also reflected a deeper dilemma for the SDA’s leaders, who were simultaneously expressing their attachment to the territorial integrity of Bosnia-Herzegovina and to the political sovereignty of the Muslim nation. These two principles were sometimes at odds with each other, as we have already seen with the Muslim “national affirmation” of the communist period or the failed attempt at the “historic Serbo-Muslim agreement” in August 1991. The potential contradictions between these two principles became clearly apparent when the SDA, while defending the territorial integrity of Bosnia-Herzegovina, created the National Muslim Council of the Sandžak (Muslimansko nacionalno vijeće Sandžaka—MNVS) in May 1991, then organized a plebiscite on October 25, 1991 in this region nestled between Serbia and Montenegro, on “the political and territorial autonomy of the Sandžak, with the right to attach itself to one of the sovereign republics [of the Yugoslav federation].”11 Thus, the SDA’s leaders were no less opportunistic in their use of the principles of territorial integrity and self-determination than the other nationalist players in the Yugoslav space.

Similar ambiguities were on display in the political alliances that the SDA formed between December 1990 and April 1992. Bosnia-Herzegovina’s march towards independence caused increasingly heated conflict between the SDA and the SDS, while bringing the SDA closer to the civic parties as the latter progressively came to term with the demise of Yugoslavia. However, the SDA’s closest ties continued to be with the HDZ, even though this Croat party was also forming “autonomous Croat regions,” and its president, Stjepan Kljujić, a moderate nationalist, was replaced by Mate Boban in February 1992. Moreover, at no time did the SDA renounce the government coalition that it had formed with the SDS and HDZ since November 1990. Yet this coalition between nationalist parties implied a sharing of leadership positions according to the “national key” principle, which sharpened interethnic rivalries for control of ministries, administrations, and state-owned enterprises. At the same time, on the local level, the battles for power between nationalist parties caused city councils to break up, with parallel monoethnic councils being formed. Lastly, the SDA and the other nationalist parties shared a quiet hostility towards the civic forces that were mobilizing against the risks of war, expressing their views on Bosnian television, in the daily Oslobođenje (“Liberation”) and through trade-union organizations. Through its actions, the SDA also contributed to the dismantling of the state apparatus in Bosnia-Herzegovina in favor of communitarian networks, and to a worsening of interethnic tensions within Bosnian society.

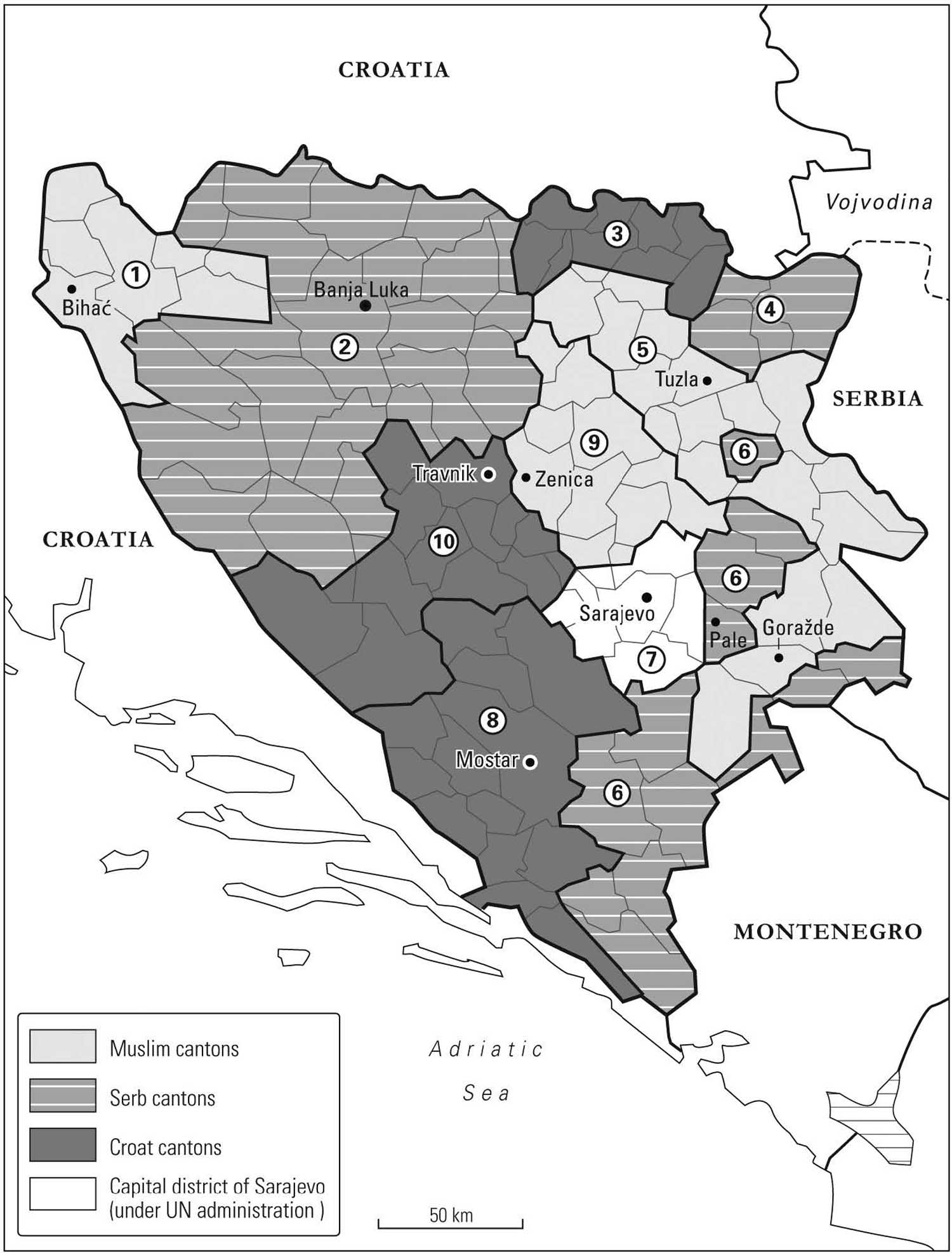

In this context, one last question about the SDA’s attitude—and perhaps the most important question of all—involves its choices in the face of the risks of war, which grew sharper between December 1990 and April 1992. There is no doubt that the SDS and the Yugoslav Army bear the primary responsibility for the war that broke out in Bosnia-Herzegovina on April 6, 1992, as shown by the magnitude of their military preparations and the increased number of armed incidents that they provoked in the preceding months. However, the SDA’s leaders appear to have accepted the idea of armed confrontation very early on: in February 1991, Izetbegović told the Bosnian Parliament that “for sovereign Bosnia, I would sacrifice peace; for peace, I would not sacrifice Bosnia-Herzegovina.”12 In the same period, the SDA was launching the initial preparations for the creation of the Patriotic League (Patriotska liga—PL), a paramilitary organization tightly bound to the party. Four months later, on June 10, 1991, a National Defense Council (Savjet za narodnu odbranu) was founded. Presided by Izetbegović, it brought together the representatives of the main political and cultural organizations of the Muslim community. Thus, the SDA created its own paramilitary forces, in parallel to the Bosnian Territorial Defense and outside any legal framework. In the months that followed, the escalating warfare in Croatia and the concentration of Yugoslav Army troops in Bosnia-Herzegovina increasingly encouraged the SDA’s leaders to place their hopes on an internationalization of the Bosnian crisis without interrupting their military preparations. However, this strategy of internationalization quickly showed its limitations. In January 1992, the UN refused to preventively expand the UNPROFOR’s mandate to Bosnia-Herzegovina. One month later, Jose Cutilheiro, the European negotiator in charge of talks about the future of Bosnia-Herzegovina, borrowed the HDZ’s idea of creating ethnic cantons, and proposed a partition plan that scrupulously respected ethnic majorities on a municipal level (see Map VII).

By convoking a self-determination referendum and by promoting a cantonization plan, the European Community contributed to the outbreak of war by reducing interethnic relations to a zero-sum game. Therefore, it is unsurprising that the period from the self-determination referendum until the international recognition of Bosnia-Herzegovina was also the period in which the country went from peacetime to war. To convince the Bosnian Muslims to vote in favor of independence, the SDA explained that this was the best means to obtain the international community’s protection and to avoid war: in this context, many Muslim voters were not expressing a desire for independence so much as a plea for security addressed to the European Community. But on the evening of March 1, 1992, the SDS set up armed barricades around Sarajevo to demand that negotiations resume on the future of Bosnia-Herzegovina. On February 22, and then again on March 18, the three nationalist parties gave their support to the Cutilheiro Plan, before Izetbegović rescinded his signature. On April 6, the European Community recognized the independence of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The next day, the United States followed suit, while Serb deputies met in Pale, a small town in the heights dominating Sarajevo, and proclaimed the independence of the self-styled “Republika Srpska” (“Serb Republic”). On the ground, the number of armed incidents increased, and in Sarajevo, Serb snipers fired on tens of thousands of peaceful demonstrators who had gathered in front of the Bosnian Parliament to call for the nationalist parties to leave, bearing portraits of Tito, in a pathetic appeal to a now-defunct central power. As the nation-state principle triumphed in the Yugoslav space, the territorial claims of Serbia and Croatia, as well as the growing divergences between the nationalist parties, pushed Bosnia-Herzegovina into war.

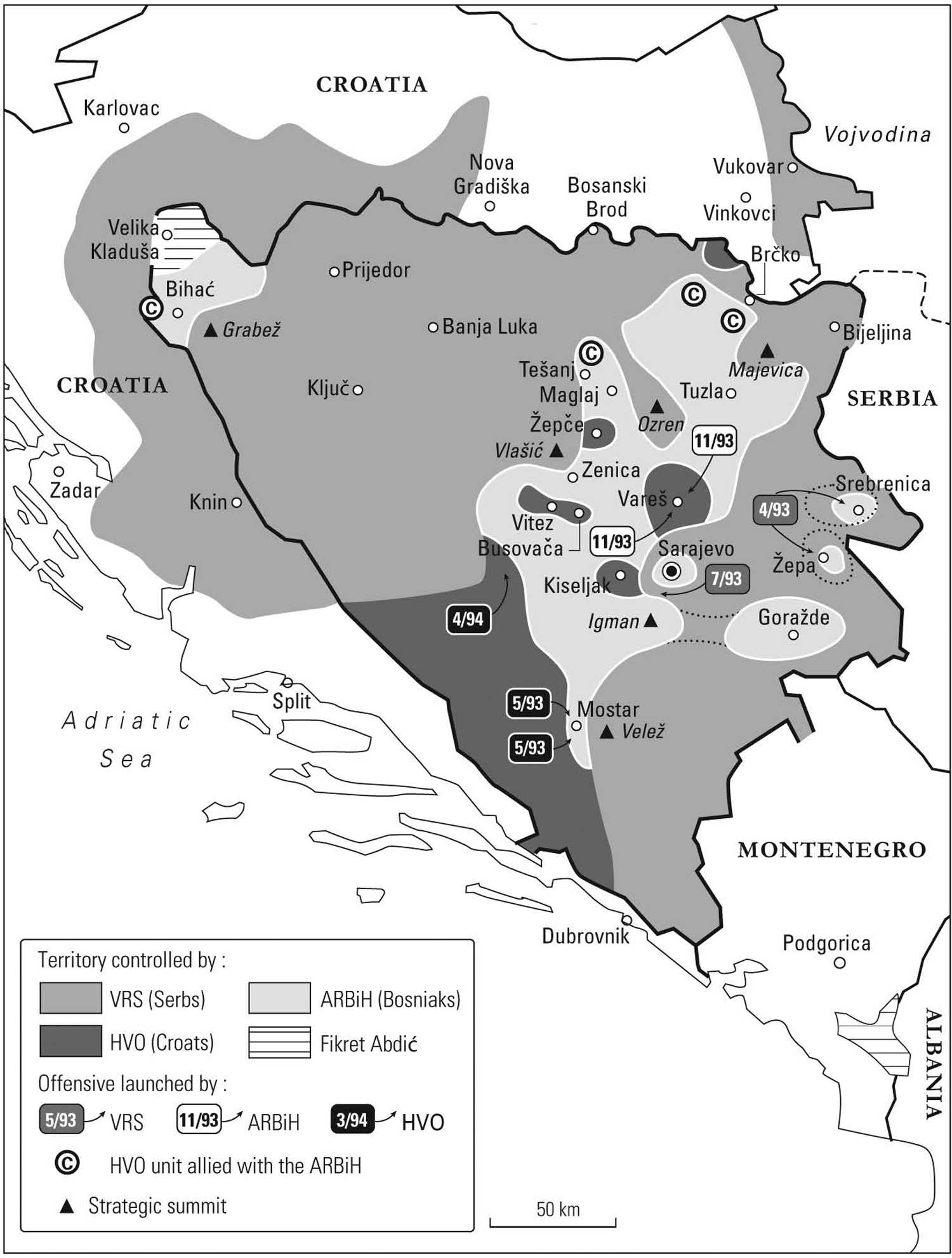

As soon as it broke out, the Bosnian war combined aspects of an outside aggression and a civil war. Outside aggression because the “Republika Srpska” enjoyed support from neighboring Serbia and the Yugoslav Army, which merged with Serb-controlled municipal territorial defense forces on May 19, 1992 to form the Army of Republika Srpska (Vojska Republike Srpske—VRS). This outside logistical support explains why a quasi-state such as the “Republika Srpska” was able to control 60 percent of Bosnian territory in just a few weeks (see Map VIII). However, the Bosnian conflict was also a civil war, as its origins lay partly with internal political disagreements within Bosnia-Herzegovina, and as most combatants were Bosnians, even though various militias from Serbia played an important role in the first weeks of the war. Serb forces, thanks to their overwhelming military superiority, besieged the town of Sarajevo. In conquered municipalities where Muslims or Croats were the majority, “crisis staffs” (krizni štabovi) implemented a particularly harsh ethnic cleansing policy. This first wave of violent expulsion of non-Serb populations resulted in several thousand civilian victims in some places, causing one and a half million refugees to flee elsewhere in Bosnia-Herzegovina or to neighboring countries, chiefly Croatia. The resistance to the Serb military offensive was organized around the Bosnian Territorial Defense, various Muslim militias (whether or not linked to the Patriotic League), and the Croat Defense Council (Hrvatsko vijeće obrane—HVO), a paramilitary force created by the HDZ on April 8, 1992 and joined in Herzegovina by many Muslims seeking arms. On July 5, the Territorial Defense and the Muslim militias merged to form the Army of the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Armija Republike Bosne i Hercegovine—ARBiH), but the HVO refused to join this new army.

Map VIII Frontlines in Bosnia-Herzegovina (April 1992–March 1993).

The war’s first months were crucial not only for setting the frontlines, but also for crystallizing certain political choices, as well as the balance of powers, on each side. As the two SDS members of the Collegial Presidency had stepped down on April 7, they were supposed to be replaced by the Serb candidates from the civic parties that had received the most votes in the November 1990 elections. However, the SDA did not make this replacement until the anti-war demonstrations had died out in Sarajevo and Sefer Halilović, the military chief of the Patriotic League, had been appointed to head the newly-formed ARBiH. Only on May 31 did Izetbegović yield to the demands of the civic parties, stepped down from the SDA’s presidency, and integrated the Serb representatives of the civic parties in the Collegial Presidency. A month later, this presidency adopted a Platform for Action of the Presidency of Bosnia-Herzegovina in Wartime, written by the Muslim Fikret Abdić, the Serb Nenad Kecmanović, and the Croat Stjepan Kljujić.13 This platform affirmed that Bosnia-Herzegovina was “the sovereign and independent state of its citizens, of its constituent and equal nations, the Muslims, Serbs and Croats, and of the members of the other nations that live there,” and specified that “the three constituent Muslim, Serb and Croat nations have their own national interests, but they also have interests that derive from a centuries-long tradition of coexistence.” This platform called for the creation of a Chamber of Nations within the Parliament, where the decisions involving the vital interests of the constituent nations would be made consensually. However, it warned that “Bosnia-Herzegovina will not accept negotiations based on the creation of ethnically pure territories or the regionalization of Bosnia-Herzegovina according to exclusively ethnic criteria.”14

The June 26, 1992 platform thus opposed the creation of ethnically homogenous territories, proposing instead a consociational, non-territorial organization for relations between the constituent nations. It was adopted unanimously by the Collegial Presidency, but at the same time, ethnic homogenization and territorialization was also at work in territories controlled by the ARBiH and the HVO. Indeed, beginning in the early months of the war, the HDZ monopolized power in Croat-majority towns, and the level of intimidation and violence aimed at non-Croat populations increased. In the town of Vareš in central Bosnia, the HDZ overthrew the city council held by the civic parties and imposed its own crisis staff. On July 3, a “Croat Community of Herceg-Bosna” gathered all the territories under HVO control, a clear sign that the HDZ was opting for the creation of a Croat quasi-state.15 In this context, a rapprochement quickly began to take shape between Serb and Croat nationalists. As early as May 6, HDZ president Mate Boban met secretly in Graz with Radovan Karadžić, the president of the “Republika Srpska,” to define the border between the future Serb and Croat entities. Despite these political and military changes, the SDA did not break its alliance with the HDZ: the Bosnian government was headed by a prime minister from the HDZ (Jure Pelivan then Mile Akmačić), and the civic parties held only a few portfolios of secondary importance. In November 1992, the SDA also agreed for Stjepan Kljujić to be replaced (unconstitutionally) by Miro Lazić (HDZ) in the Collegial Presidency. More generally, the SDA tolerated the HDZ’s hegemony in Croat regions, and even condemned the creation in Mostar of a Council of Muslims of Herzegovina that was hostile to the HDZ and led by the town’s mufti Seid Smajkić. The stance taken by the SDA’s leaders is partly attributable to important strategic considerations: the HDZ’s participation in Bosnian institutions was crucial to their international legitimacy, the HDZ’s political hegemony in Herzegovina was the trade-off for the free flow of weapons towards territories under the ARBiH’s control, and the latter could hardly afford to open a second front against the HVO. However, the SDA’s alliance with the HDZ was also due to the fact that, as a Muslim nationalist party, it considered the HDZ to be the sole legitimate representative of the Croat community, and thus an indispensable counterpart. By contrast, it viewed the civic parties as minor players with no real legitimacy. Thus, in November 1992, the SDA’s governing bodies rejected their proposal for a “Bosnian patriotic front,” choosing instead “the coalition of the SDA and the HDZ, as the main and mutually recognized vehicles for the political will of the Muslim and Croat nations in Bosnia-Herzegovina.”16 This communitarian rationale pushed the SDA, in turn, to monopolize power in the ARBiH-controlled territories, to form its own crisis staffs in many municipalities, and to attack the few bastions of the civic parties, such as the social-democratic city council of Tuzla, led by its mayor Selim Bešlagić, or the Zenica steel plant. The SDA’s attitude partly explains why Nenad Kecmanović, a Serb member of the Collegial Presidency, secretly left Sarajevo in August 1992 to seek refuge in Belgrade.17

From the early months of the war, fighting broke out sporadically between the ARBiH and HVO as they pillaged the barracks of the Yugoslav Army and delimited their respective areas of influence. At the same time, in Herzegovina, the Muslim fighters of the HVO gradually left this corps to join the ARBiH, which was still in its nascent stages in the region. However, to understand why wide-scale conflict between Muslims and Croats erupted in spring 1993, we must take into consideration the ways in which the Bosnian conflict was internationalized between April 1992 and May 1993. Emboldened by the recognition of Bosnia-Herzegovina by the Member States of the European Union, the United States and many Muslim countries, Bosnian authorities began in April 1992 to request military intervention under Chapter VII of the UN Charter and a lifting of the arms embargo that the UN had imposed on all states of the former Yugoslav federation in 1991. However, the military option was rejected by the states involved in the resolution of the Bosnian war in favor of a number of diplomatic and humanitarian initiatives. In May 1992, the UN Security Council voted for economic sanctions against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia; these sanctions would be made harsher over the course of the conflict, despite Russia’s reluctance. In June, the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) deployed in Croatia was given an extended mandate that covered Bosnia-Herzegovina: UNPROFOR was to reopen the Sarajevo airport and to ensure the unhindered circulation of humanitarian convoys. Lastly, in October 1992, a no-fly zone was created over Bosnia-Herzegovina, to be enforced by NATO aviation. At this stage of the conflict, however, the international action with the greatest impact was the peace talks mediated by UN Special Representative, Cyrus Vance, and European Union representative, David Owen.

After the Cutilheiro Plan fell through, a new international conference on the former Yugoslavia was summoned in July 1992, with the aim of negotiating a peace plan with the various protagonists of the Bosnian war. On January 2, 1993, Vance and Owen made public a peace plan whereby Bosnia-Herzegovina would be turned into a decentralized state, with a Collegial Presidency and a central government, but divided into ten ethnic provinces, three of which would be Muslim, three Serb, and three Croat, with one “neutral” province covering the Sarajevo region (see Map IX). These provinces would wield most political powers, but would have no international political subjectivity, and would be subject to complex consociational rules to avoid discrimination against local national minorities. However, far from settling the war, this plan actually caused it to spread to regions populated by Croats and Muslims. The HDZ, with the Croat provinces covering the bulk of Herzegovina and central Bosnia, eagerly accepted the Vance–Owen Plan and required that the ARBiH withdraw from areas allocated to the Croat provinces. Beginning in March, fighting between Croats and Muslims spread throughout central Bosnia, then into Herzegovina. On May 9, 1993, the Battle of Mostar began. In the following months, the HVO carried out a systematic ethnic cleansing in the regions it controlled, while the ARBiH did so on an occasional basis. By endorsing the rationales of ethnic territories that were at the heart of the Bosnian war, this peace plan actually only encouraged violence.

Map IX The Vance–Owen Plan (January 1993).

For the SDA’s leaders and all the inhabitants of ARBiH-controlled territories, the fighting between Croats and Muslims was a diplomatic, military, and humanitarian catastrophe. Diplomatically, this fighting strengthened the view of a “war of all against all,” hindering the internationalization of the conflict. Therefore, whereas the Vance–Owen Plan called for military intervention against whichever party caused the plan to fail, the “Republika Srpska” rejected it with impunity in May 1993. The Bosnian authorities denounced Croatia’s military aid to the HVO, describing it as a second aggression against Bosnia-Herzegovina, but did not call for international sanctions against Croatia, in an effort to avoid consummating the rift between Croats and Muslims. Militarily, the ARBiH-controlled territories found themselves completely surrounded by the VRS and the HVO (see Map X), and the main flows of weapons through Herzegovina were interrupted. Lastly, from a humanitarian perspective, this fighting caused hundreds of thousands of additional refugees to flee, while making the delivery of international aid extremely difficult. This situation grew even worse in March 1993, when the VRS launched a vast offensive in eastern Bosnia, significantly reducing the size of the Muslim enclave of Srebrenica and threatening to capture the town. General Philippe Morillon, the UNPROFOR commander in Bosnia-Herzegovina, intervened at the last minute to prevent a major catastrophe; six UN-protected “safe areas” were created in May: Sarajevo, Tuzla, Bihać, Srebrenica, Goražde, and Žepa (see Map X). This creation of “safe areas” changed the mandate of UNPROFOR and NATO air forces considerably, but it did not provide effective protection for these towns, a fact that became cruelly evident when Srebrenica fell in July 1995. In addition, the “safe areas” came in place of the direct military intervention that the inhabitants and leaders of ARBiH-controlled regions were hoping for.

The situation caused by fighting between Croats and Muslims inevitably affected the objectives and strategies of the SDA’s leaders. The most surprising, given the circumstances, was their reluctance to end their coalition with the HDZ: Prime Minister Mile Akmačić remained formally in office until October 1993, and the two Croat members of the Collegial Presidency that belonged to the HDZ, after resigning in June 1993, were not replaced until four months later. However, the way in which the SDA defined its war objectives underwent considerable transformations in the same period. In December 1992 in Sarajevo, a Congress of Bosnian Muslim Intellectuals declared:

The destiny of the Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks) is tied to the existence of the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Any challenge to the territorial integrity and independence of the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina caused by expansionist aspirations towards its territory represents a threat to the physical and spiritual existence of the Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks).18

Map X Frontlines in Bosnia-Herzegovina (April 1993–March 1994).

In the difficult wartime conditions, the Muslim intellectuals with close ties to the party affirmed that there was a tight connection between the Muslim nation’s political sovereignty and the defense of the territorial integrity of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Over the following months, however, this twofold objective would be challenged. To understand why, we must again turn to the international context of the Bosnian conflict.

On June 16 1993, Slobodan Milošević and Franjo Tuđman took advantage of the failure of the Vance–Owen Plan, followed by Cyrus Vance’s resignation and replacement by Thorvald Stoltenberg, to present a joint proposal for Bosnia-Herzegovina to be partitioned into three ethnic republics. Eight days later, the SDS and the HDZ signed an agreement on the “confederalization” of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and the Croat representatives stepped down from the Bosnian Collegial Presidency. In the following weeks, the VRS captured Mount Igman, cutting off the ARBiH’s sole supply route for Sarajevo. Only pressure from the UN was able to force Serb forces to withdraw, with “demilitarization” of Mount Igman and a discreet return of the ARBiH. In parallel, on August 20, international mediators Owen and Stoltenberg published a new peace plan inspired by the Milošević–Tuđman proposal and calling for Bosnia-Herzegovina to become a union of three ethnic republics, with the following territorial breakdown: Republika Srpska 51 percent, Bosnian Republic 30 percent, Croat Republic 16 percent, and Sarajevo and Mostar (under international administration) 3 percent (see Map XI).

Under this plan, shared institutions were reduced to a minimum, with each ethnic republic having its own Constitution, albeit without international political subjectivity. The triumph of the nation-state principle thus seemed complete, and Bosnia-Herzegovina was apparently destined to disappear and be replaced by three ethnically homogenous quasi-states. At that moment, the Bosnian Muslims were not only completely encircled on a military level, but also totally isolated diplomatically. Making this desperate situation even worse, the Owen–Stoltenberg Plan triggered serious tensions within the Collegial Presidency between representatives of the civic parties (who were hostile to the plan but unwilling to continue a war that was ravaging Bosnian society), Izetbegović and Ejup Ganić (in favor of renegotiating this plan) and Fikret Abdić (who wanted to accept the plan immediately and unconditionally). Over the summer, Abdić stepped down from the Collegial Presidency to return to his stronghold in Cazinska Krajina and came into conflict with local leaders of the SDA. In September, he proclaimed an “Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia,” whose militias quickly confronted the ARBiH’s 5th Corps. Just as the Vance–Owen Plan had fostered conflict between the Croats and Muslims, so the Owen–Stoltenberg Plan triggered conflict among Muslims themselves.

Thus, for the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina, summer 1993 was the worst period of the war, when their political and physical survival was under the greatest direct threat. Abdić underscored this fact, stating that “continuing this bloody war could lead our population to its physical disappearance,”19 as did Izetbegović, who warned that “continuing the war threatens the very biological existence of the nation.”20 So why were the two men not in agreement? Apart from personal ambitions, there were real political and strategic disagreements between Izetbegović and Abdić. The latter wanted the Owen–Stoltenberg Plan to be accepted unconditionally. He considered stopping the fighting to be the absolute priority, and expected that renewed trade and human interactions between the future constituent entities of Bosnia-Herzegovina would favor their gradual disappearance. Izetbegović, for his part, was not—or was no longer—the unconditional defender of a united Bosnia-Herzegovina that some have considered him to be. Indeed, the presentation of the Owen–Stoltenberg Plan and the deteriorating situation on the ground had prompted the SDA’s leaders to give priority to the Muslim nation’s survival, even if that meant sacrificing the territorial integrity of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Thus, in early August, Izetbegović said in a television interview:

Map XI The Owen–Stoltenberg Plan (July 1993).

The centre of gravity for our struggle, for the struggle of our soldiers who have succeeded in preserving Bosnia-Herzegovina, must be the Bosniak, Muslim nation, which is the target of aggression. The aggressor’s goal, first and foremost, is not so much the annihilation of Bosnia-Herzegovina as a state as the extermination of the Muslim nation.21

The SDA’s leaders thus dissociated the Muslim nation’s physical survival from Bosnia-Herzegovina’s territorial integrity, accepting (at least in part) the principle of a partition along ethnic lines, and putting off its possible gradual reintegration to a period after the war was over.

Speaking to the Bosnian Parliament on August 27, Izetbegović stated: “our duty these days is to save what can be saved of Bosnia. This is our duty here and today so that perhaps, in the future, all of Bosnia can be saved.”22 In appearance, this position is not very far removed from the one that Fikret Abdić was defending. In fact, the disagreement between the two men did not relate to the principle of partitioning Bosnia-Herzegovina along ethnic lines, but rather on the actual delineation of the ethnic republics. Abdić accepted the Owen–Stoltenberg Plan unconditionally, whereas Izetbegović (still speaking to the Bosnian Parliament) demanded that the proposal be adjusted so that the Muslim majority regions of eastern and western Bosnia would be attached to the future Bosnian Republic, so that this entity would have sea access, and so that the peace plan would be guaranteed by the United States and NATO.

One month later, on September 27, 1993, a Bošnjački sabor (Bosniak Assembly) met in Sarajevo, bringing together the main political, military, religious, and intellectual representatives of the Muslim nation. Its initial purpose was to give its opinion of the Owen–Stoltenberg Plan. In his opening speech, Izetbegović criticized this plan less for establishing an ethnic partition of Bosnia-Herzegovina and more for leaving “in the aggressor’s hands vast regions formerly populated by a majority of Muslims, [and] ethnically cleansed during the war.”23 During the Bošnjački sabor, the representatives of these regions were, quite logically, among the fiercest opponents to the peace plan. The representatives of the civic parties, for their part, refused any ethnic partition in the name of a plurinational Bosnia-Herzegovina. For example, Nijaz Duraković, the president of the Social Democratic Party (Socijaldemokratska partija—SDP, the former communist SKBiH), warned that the Owen–Stoltenberg Plan:

means additional population displacements, it does not stop ethnic displacements, because what is left in the Serb and Croat Republics would immediately [and] quickly be cleansed, and most likely this same process would extend to what we would call the Bosnian Republic, thus [it would mean] further tragedies for hundreds of thousands of people and it would be, I am convinced, the sign of the disappearance of the state of Bosnia-Herzegovina as such, but also the disappearance of the Muslim nation or the Bosniak nation, no matter [which name we use for it], as such.24

Enes Duraković, president of the cultural society Preporod and chairman of the Bošnjački sabor session, had a stance that was more ambiguous, but extremely significant, when he summarized the choice facing the Bošnjački sabor as follows:

The Bosniaks have done everything to preserve Bosnia as it has existed over its thousand-year history, in other words, as a multicultural, multinational and multiconfessional community. In this period of extreme temptations, of clear genocide and of others’ refusal to live with us, the Bosniaks have done everything not to obtain their [own] national state. This is probably a unique case of a nation refusing such a “gift” and the world is stunned. It is stunned because it did not understand us before, and it does not understand us today. Today they are forcing us [to opt for a nation-state] and the decision on this topic will be made by the Bošnjački sabor and the Parliament of the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina.25

Enes Duraković’s words underscore the fact that many members of the Bošnjački sabor accepted the nation-state rationales at work in the Yugoslav space only because they were forced to by the military and diplomatic balance of powers. Some of the SDA’s leaders, however, viewed the possibility of founding a small Muslim nation-state more serenely. For example, Edib Bukvić, an SDA cadre with ties to the pan-Islamist current and a candidate for prime minister, declared:

The current Bosnia-Herzegovina, with its three nations, has become unrealistic. After such a genocidal war, the Muslims, the Serbs and the Croats will for a long time be unable to create any sort of common state… In light of what has just been said and our real possibilities, it is indispensable to define the limits of a state for the Muslim nation.26

In this attempt to delineate a small Muslim nation-state, the main concern of the SDA’s leaders may not have been the lost Muslim-majority territories. Hakija Meholjić, one of the delegates of the Muslim enclave of Srebrenica, even accused Izetbegović of floating the idea of trading this enclave for some suburbs of Sarajevo held by Serb forces.27 But the SDA’s leaders were inflexible on the future Bosnian Republic’s access to the Adriatic Sea (at Neum) and the Sava River (at Brčko), which was needed to avoid being completely surrounded by the Serb and Croat republics. In the end, 218 members of the Bošnjački sabor (out of 349) voted in favor of the Owen–Stoltenberg Plan provided Izetbegović’s demands were met, whereas fifty-three voted for it unconditionally and seventy-eight voted for it to be purely and simply rejected.28 The Bošnjački sabor thus rejected the international community’s peace plan as it was presented and was in open opposition to the international community for the first and only time during the conflict. During the same session, the Bošnjacki sabor voted to replace the national name “Muslim” with “Bosniak”: at the most critical moment of the war, the representatives of the Muslim/Bosniak nation reasserted its political sovereignty loudly and clearly, and attempted to resolve some of its identity dilemmas, as we shall see in Chapter 6.

The Bošnjački sabor’s proceedings enable us to better understand the confrontation between Fikret Abdić and the SDA’s leaders. For Abdić, the physical survival of the Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina required them to renounce their own political sovereignty and for the future Bosnian Republic to declare allegiance to Serbia or Croatia—or to both at the same time. Abdić thus adopted the strategies used by the Muslim political elites before the Second World War: namely, renouncing any national project for the Muslim community. From this standpoint, the issue of the borders of the Bosnian Republic was secondary. However, Abdić’s strategy could only lead to a situation of powerlessness and subordination, as shown by the events in his “Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia.”29 The SDA’s leaders, as well as a large number of politicians and intellectuals, believed that the political sovereignty of the Bosniak nation was an absolute prerequisite for its physical survival. Therefore, the Bosnian Republic had to be economically and militarily viable, without depending on its neighboring countries, hence the importance of the borders and, in particular, access to the Adriatic Sea and to the Sava River.

Autumn 1993 was undeniably a time when the SDA’s leaders gave in to the nation-state rationales that held sway over the Yugoslav space and considered creating a small Bosniak nation-state. Just after the Bošnjački sabor, Edhem Bičakčić (a co-defendant in the 1983 trial and vice president of the SDA) explained:

The SDA will support a state for the Bosniak nation and the citizens who live on this territory. This means that the Bosniaks will be those who will form this state community, and the other citizens will be guaranteed all human rights according to the highest European standards… It will be a secular state, but it will be the state of the Bosniak nation. It will constitute this state and the other nations will have the rights of [national] minorities.30

Concretely, while rejecting the Owen–Stoltenberg Plan’s territorial breakdown, Izetbegović signed a bilateral agreement with Momčilo Krajišnik, representative of the “Republik Srpska,” on September 16. This agreement gave each of the ethnic republics of Bosnia-Herzegovina the right to secede after a two-year transitional period.31At the same period, the newspaper Ljiljan asked:

If Alija Izetbegović cannot prevent the partition of Bosnia-Herzegovina, why not ask for the same principle to be applied to all of the former Yugoslavia and integrate the Muslim Sandžak region into the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina?32

Indeed, in autumn 1993, the National Muslim Council of the Sandžak published a Memorandum on the Establishment of a Special Status for the Sandžak. However, this new request for autonomy for the Sandžak only exacerbated the conflict within the local branch of the party opposing its president Sulejman Ugljanin and secretary general Rasim Ljajić.33

But did the SDA’s leaders support the idea of a small Bosniak nation-state with enthusiasm or regret? Džemaludin Latić, a close associate of the Bosnian President, believed that Alija Izetbegović was “forced to accept this vulgar concept [of a nation-state].”34 Yet Adnan Jahić, another influential representative of the pan-Islamist current, believed that “Alija Izetbegović’s eternal dream, as a Young Muslim, was and is still the creation of a Muslim state in Bosnia-Herzegovina; now this dream is coming true, and ‘that does not really bother him.’”35 Who better understood Alija Izetbegović’s feelings, Latić or Jahić? In his memoirs published in 2001, Izetbegović himself presented the Bošnjački sabor’s vote eight years earlier as a refusal of any ethnic partition of Bosnia-Herzegovina. This is, at the very least, a simplistic presentation of the facts.36

Nevertheless, there is one major certainty about this complex period. In 1993, some of the SDA’s leaders—beginning with those connected to the pan-Islamist current—were tempted by the idea of a small Bosniak nation-state, but this was never used as a justification for ethnic cleansing. Granted, ARBiH units committed serious crimes, notably against the Serb population of Sarajevo and the Croat population of central Bosnia. But the ARBiH did not resort to ethnic cleansing systematically, and did not elevate it to the level of a legitimate instrument for creating a Bosniak nation-state.37 To understand this essential fact that set the SDA apart from the SDS, the HDZ and their related armies, several factors must be considered. There were some strategic considerations: for the ARBiH, carrying out systematic ethnic cleansing would have tarnished the international legitimacy of the Bosnian authorities, made the Bosnian conflict look like a “war of all against all,” and pushed tens of thousands of men into the arms of the Serb VRS and the Croat HVO at a time when these armies were sorely lacking in recruits. However, beyond this strategic dimension, there were deeper reasons why the leaders of the SDA and the ARBiH rejected ethnic cleansing. First of all, the Bosniak political and military leaders were not all nationalists. In the ARBiH, notably in its 2nd Corps based in Tuzla, many officers coming from the Yugoslav Army were connected to the civic SDP rather than the nationalist SDA. Even within the SDA, Izetbegović and his close collaborators were originating from the pan-Islamist current. Yet from a pan-Islamist standpoint, the Serbs and Croats were not “foreign elements” to be expelled from the national body, but “people of the Book” (ahl-al kitab) to be protected in exchange for their allegiance. At the same time, this refusal of ethnic cleansing was a way to assert the European identity and moral superiority of the Bosniak nation, as we shall see in Chapter 7. However, the most important factor was that the future Bosnian Republic could not be a catalyst for later reintegration of Bosnia-Herzegovina unless it ensured the safety of the Serbs and Croats living on its territory. Even more so, the protection of the local Serb and Croat populations was a condition sine qua non for the Bosniak nation to be at the heart of this reintegration. As Izetbegović said, speaking again to the Bošnjački sabor in July 1994:

Our struggle for the integration of Bosnia will largely depend on us, on what we are ourselves, on what we want and what we can do. On our will and our capacity to make the part of Bosnia that we control into a modern, democratic and free country… Bosnia cannot bear intolerance. Such as it is, plurinational and multiconfessional, it seeks someone that this mosaic does not bother. Churches and cathedrals do not bother us; we have learned to live with people who think and feel differently, and we consider that this is an advantage for us. This is why we Bosniaks, we the Muslim people of Bosnia, are predestined to be at the forefront of the reintegration of Bosnia. Not so that Bosnia will be a homogenous state—it cannot be—but so that it is and remains whole.38

The political crisis that the Muslim community underwent in summer 1993 illustrates the exhaustion of nationalist mobilizations in Bosnia-Herzegovina. After a year and a half of war, the three communities endured centrifugal forces that threatened their cohesion and their capacity for action. On the one hand, the various peace plans heightened tensions between nationalist leaders and the representatives of local populations threatened by the different partition plans. On the other hand, entangled frontlines fed parochial interests, encouraged smuggling activities between armies that were supposedly enemies, and resulted in a rising divide between mafia-like military units controlling the black market and underpaid, under-equipped local units. In the “Republika Srpska,” a mutiny of several military units in Banja Luka in September 1993 revealed the poor morale afflicting Serb combatants. Everywhere, the civilian population rapidly sank into poverty and became dependent on international humanitarian aid. At the same time, in Serbia and Croatia, the nationalist mobilizations of the early 1990s ran out of steam due to divisions within the political elites and a growing apathy amongst the population. Lastly, as the war carried on, the humanitarian catastrophe caused by the conflict and by ethnic cleansing threatened the credibility of international organizations and the major Western powers. The West, which had given priority to the nation-state principle in the solution of the Yugoslav crisis when it recognized Slovenia and Croatia in January 1992, gradually had to adjust this stance with regard to Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The Bosniak community had been the first of the three communities to fall into overt political crisis when Fikret Abdić seceded in September 1993; it was also the first community to exit the crisis. On October 25, 1993, the Bosnian Collegial Presidency stripped Abdić and the two HDZ representatives of their powers, naming three representatives of the civic parties in their place: Nijaz Duraković (president of the SDP), Ivo Komšić,39 and Stjepan Kljujić.40 On the same day, Haris Silajdžić, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and an influential member of the SDA, became prime minister of a government whose ministers came from the SDA and the civic parties. In his governmental program, Silajdžić mentioned the priorities of strengthening the army, setting up a war economy, bringing supplies to the population, and restoring the rule of law, because “any violence, injustice or illegal actions against individuals … sparks a general feeling of insecurity among the citizens.”41 In the weeks that followed, various mafia-like military units were eliminated in Sarajevo and central Bosnia, Sefer Halilović was replaced as the ARBiH commander-in-chief by General Rasim Delić, and the military hierarchy was taken in hand. It may appear surprising that the SDA’s leaders grew closer to the civic parties at the very moment when they appeared to accept a partition of Bosnia-Herzegovina along ethnic lines. Yet there are several explanations for this apparent paradox. Diplomatically isolated, having broken with their Croat partners of the HDZ, weakened by Abdić’s secession, they had no other choice.

Focused on reorganizing and remobilizing the territories under ARBiH control, the SDA’s leaders no longer viewed a coalition of nationalist parties as the only legitimate form of government, favoring instead other forms of communitarianism: a Croat National Council (Hrvatsko nacionalno vijeće), presided by Ivo Komšić, was created in Sarajevo in February 1994, and one month later a Serb Civic Council (Srpsko građansko vijeće), presided over by Mirko Pejanović, one of the two Serb members of the Bosnian Collegial Presidency. Lastly, the new coalition between the SDA and the civic parties did not prevent the SDA from continuing to monopolize power in the ARBiH-controlled territories; as the army was taken in hand, many officers with ties to the SDA were promoted, while the takeover of state-owned enterprises deprived the civic parties of a good portion of their material support, notably in the Tuzla region.

The exhaustion of nationalist mobilizations beginning in 1993 was similar, in some respects, to what the Ustasha and Chetnik movements had experienced during the Second World War. In both cases, plans for homogenous nation-states were shattered due to their own internal contradictions, leading to a deep crisis within their respective communities. Thus, in late 1993, after the Bosniak community gathered new strength, the Croat community’s political and military underpinnings collapsed. Overstretched between its stronghold in western Herzegovina and the Croat enclaves of central Bosnia and Posavina, the “Croat Republic of Herceg-Bosna” struggled to maintain its political cohesion (see Map X). In central Bosnia, the HVO bought arms and munitions from the Serb forces in order to face the ARBiH, whereas in Posavina, the HVO remained an ally of the ARBiH. Everywhere, the HVO’s local units were involved in all sorts of smuggling: humanitarian aid, petrol, weapons, and refugees. In Croatia itself, the Tuđman regime’s support for the Croat “Herceg-Bosna” sparked criticism from the opposition parties in Parliament and from the Catholic Church, and triggered a split within the HDZ. This was the backdrop against which, in November 1993, the ARBiH captured the Croat enclave of Vareš, thus restoring territorial continuity between the towns of Zenica and Tuzla. In central Bosnia, “Herceg-Bosna” was reduced to a few exhausted, isolated enclaves. For the first time, Bosniak leaders were the victors, and they had to decide how to deal with the recaptured territories. However, the case of Vareš shows that the Bosniak leaders were unable to make sure that the local Croat population would stay put. The HVO organized the evacuation of Croat civilians through areas under Serb control, several ARBiH units pillaged the town, and the SDA appointed one of its leaders to be in charge of the city council, rather than restoring the local civic majority that had been elected in 1990. From this standpoint, the capture of Vareš cast a dark shadow over the SDA’s capacity to carry out the expected reintegration of Bosnia-Herzegovina into a single political entity populated with different communities.

In the following months, several major geopolitical and political changes occurred. First and foremost, the United States became more and more involved in the settlement of the Bosnian war. In February 1994, the American administration supported NATO’s ultimatum to the VRS, demanding that it withdraw its heavy artillery stationed around Sarajevo. A few weeks later, the United States gave its implicit approval for Iranian weapons shipments to the ARBiH, thus indirectly lifting the UN arms embargo. The American involvement was a crucial success for Bosnian diplomats, who had stopped believing in the intervention capacities of the European Union and the United Nations. At the end of 1993, the United States also gave their support to the proposal by the Croat National Council to transform Bosnia-Herzegovina into a consociational state divided into cantons. The US State Department proposed using this model to end the fighting between Croats and Bosniaks and to escape the nation-state rationales that had been at work since the war started. In so doing, it forced the SDA’s leaders to reconsider their definition of the ties between Bosniak political sovereignty and Bosnian territorial integrity, in a very different context from autumn 1993. Indeed, at the time, the SDA’s leaders could say that they had no other possibility than to accept the partition of Bosnia-Herzegovina; six months later, their military and diplomatic situation had improved considerably, and a cantonization of ARBiH-controlled territories could give a tangible form to the idea of a gradual reintegration of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Yet if the SDA’s leaders had had difficulty accepting the idea of a small Bosniak nation-state in September 1993, five months later, they seemed to have some trouble giving up the idea.

On February 7, 1994, the Bosnian Parliament met to discuss the latest developments in the peace talks, including the proposal by the Croat National Council. Izetbegović then asked the deputies to examine all proposals without any preconceived ideas, because apart from saving the nation and state, “there are no taboo subjects.”42 Soon after, SDA deputy Muhamed Kupusović stated that only an agreement with the Serb and Croat nations, or a complete military victory, would enable Bosnia-Herzegovina to be reintegrated. He ruled out these two possibilities, considering them highly unlikely, and therefore proposed that a Bosnian Republic should be proclaimed as an “independent and democratic state for the Bosniak Muslim nation.” This republic would encompass all municipalities that had a Muslim majority before the war, with the possibility of land swaps if necessary. It would have access to the Adriatic Sea and to the Sava River, and it would ensure national minority status to the Serbs and Croats living on its territory.43 This proposal not only ran into opposition from the civic parties, but also sparked sharp tensions within the SDA parliamentary group. More generally, in early 1994, a group of Bosniak intellectuals who had been involved in the “national affirmation” of the communist period began to express their open opposition to any partition of Bosnia-Herzegovina. This revolt took shape around Enes Duraković, president of the Bosniak cultural society Preporod, and was joined by Rusmir Mahmutćehajić, a major intellectual figure of the SDA who had been close to the pan-Islamist current up to that point. The SDA’s leaders had to backtrack and give their support to the idea of cantonizing the territories controlled by the ARBiH and the HVO. On the Croat side, Krešimir Zubak took Mate Boban’s place as the leader of the HDZ in February 1994, and Croatia accepted the principle of a shared Bosniak-Croat entity—which it had refused just a few months earlier. In March 1994, negotiations began in Washington between the Bosniak and Croat delegations, and on March 18, 1994, a bilateral agreement created the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Federacija Bosne i Hercegovine). This federation would be led by a rotating Presidency,44 a bicameral Parliament,45 and a government formed on a strict basis of parity.46 It was formed of eight cantons, including four Bosniak cantons, two Croat ones, and two “mixed” ones,47 with the town of Mostar placed under European Union administration. Lastly, the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina claimed 58 percent of Bosnian territory, thus leaving open the possibility of integrating Serb-controlled territories at a later date.

The creation of the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina was, in several respects, a major turning point in the Bosnian war. On a diplomatic level, it sanctioned the central role that the United States was now playing in resolving the conflict. On a military level, it ended fighting between Bosniaks and Croats, and thus shifted the balance of powers between the ARBiH and the VRS. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, it established a territorialized form of consociationalism, in opposition to nationalist projects that had been weakened by their own contradictions. This consociationalism thus represented a new way of organizing the relations between the constituent nations of Bosnia-Herzegovina. In reality, however, the Washington Agreement proved particularly difficult to implement.

The frontlines were simply frozen, while the ARBiH and the HVO continued to behave like two potential enemies, even though the HVO allowed weapons to transit to the ARBiH again—in exchange for a certain percentage! Setting up shared institutions was extremely laborious, at both the federal and cantonal levels. In this context, the SDA and the HDZ again recognized each other’s political monopoly over their respective communities. The establishment of the Federation thus coincided with a return to an informal SDA–HDZ coalition, to the detriment of the civic parties.

Hence the HDZ demanded that Croat municipalities be created around Brčko and Tešanj, or even in Tuzla and Sarajevo, but refrained from asking for the civic city council of Vareš to be restored. Conversely, the SDA claimed the right to organize the Bosniak population in the territories under Croat control, but did not extend this claim to the civic parties. Few refugees who had been victims of ethnic cleansing returned to their homes, and the departure of Serb and Croat populations gathered pace in the territories under ARBiH control. The territorialized consociationalism devised in Washington struggled to reverse the underlying nation-state rationales behind the Bosnian conflict, and did not prompt nationalist leaders to renounce their initial political ambitions permanently. Soon after the Washington Agreement was signed, Izetbegović stated:

We have two ends: firstly, preserving Bosnia-Herzegovina as a state in its existing and internationally-recognized borders; secondly, organizing Bosnia-Herzegovina internally in such a way as to ensure the existence, identity and development of the Muslim nation. This must be a state built in such a way that the Muslim nation never again endures genocide. I have said that these are two ends. To be more precise: the second point is the end, whereas the first is the means.48

A few days later, he told the SDA’s governing bodies:

Life together is a beautiful thing, but I think and I can freely say that it is a lie … Our soldier in the mountains, suffering in the mud, does not do it for the sake of coexistence but to defend this toprak [territory], this land that they want to take away from him. He risks his life to defend his family, his land, his people.49

Against this backdrop, the SDA further consolidated its hegemony in the territories under ARBiH control. Thus, the creation of the canton of Tuzla-Podrinje in August 1994 enabled it to strip the Tuzla city council of most of the prerogatives that it had inherited from the Yugoslav self-management system. At the same time, however, the SDA’s founding core began to lose its unity. Prime Minister Haris Silajdžić saw his efforts to restore the state hampered by the renewed SDA–HDZ coalition. On the one hand, his government was completely overhauled in May 1994 to bring on board HDZ representatives, to the detriment of the civic parties. On the other hand, an SDA-HDZ mixed commission was created, led by Edhem Bičakčić (the SDA’s vice president) and Dario Kordić (the vice president of the “Croat Republic of Herceg-Bosna”). This commission, responsible for settling conflicts between the two parties, circumvented the government when it came to making important decisions. A falling-out between Haris Silajdžić and the SDA’s governing bodies was on the horizon; it finally occurred in 1995.50

The major diplomatic and political changes in 1994 did not have an immediate military impact. Thus, the VRS led an offensive against the Muslim enclave of Goražde in April 1994, stopped at the last minute by a NATO ultimatum. Seven months later, the VRS successfully countered an offensive by the ARBiH 5th Corps in Bihać. However, it was the Serb community’s turn to go through an internal crisis, just as the Bosniak and Croat communities had. Milošević’s desire to end the war brought him into opposition with the leaders of the “Republika Srpska.” In August 1994, Serbia announced an economic embargo to the “Republika Srpska” that was never fully enforced. In parallel, political tensions rose within the “Republika Srpska,” and several deputies opposed to Karadžić’s policies formed a parliamentary group around Milorad Dodik, who had been elected in 1990 on the lists of the Alliance of Reformist Forces of Yugoslavia (SRSJ). Last but not least, the population’s impoverishment, the army’s criminalization and collapse, and ever stronger international pressure increasingly sapped the morale of Serb combatants. The major Western powers hardened their stance towards the “Republika Srpska,” as shown by the gradual strengthening of economic sanctions and the increasingly important role played by NATO. In this context, a Contact Group—comprising the United States, Russia, Great Britain, France, and Germany—proposed a new peace plan in July 1994. This plan called for Bosnia-Herzegovina to be divided between the Federation (51 percent of total Bosnian territory) and a still-undefined Serb entity (49 percent). These two entities would form a Union of Bosnia-Herzegovina with very limited powers, as each entity would have its own Constitution and international political subjectivity. Speaking to the Bošnjački sabor, which was meeting again on July 18, 1994 to debate this peace plan, Izetbegović called on the participants to approve it even though it gave the Serb entity several Muslim-majority towns. According to Izetbegović:

If peace arrives, and it will not be without difficulty, then the aggressor will have to recognize Bosnia-Herzegovina and withdraw from 20% of occupied territories … This means that the struggle for liberation of the other occupied territories will have to be pursued through political means, not military. It will be a long tactical fight that will last for years, even generations, but the chances for victory are on our side.51

The idea of reintegrating Bosnia-Herzegovina in two stages, first militarily and then politically, enabled the SDA’s leaders to evade the ever-present tension between affirming the Bosniak political sovereignty and preserving Bosnian territorial integrity. In the end, the Bošnjački sabor approved the Contact Group’s plan by 303 votes out of 349. Ten days later, it was rejected by the Parliament of the “Republika Srpska.” In January 1995, in an attempt to rekindle the peace talks, France and Great Britain proposed establishing confederal ties between the future Serb entity and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, equivalent to the ties between the Federation and Croatia, as stipulated in the Washington Agreement. After some hesitations, the SDA eventually conceded that “special ties are possible between the Bosnian Serbs and Serbia, on the condition that similar ties [are formed] between the Bosniaks of Bosnia and those of the Sandžak.”52

In spring 1995, the war suddenly gained pace. In early May, in Croatia, the Croatian Army won its first major victory against the “Serb Republic of Krajina” by regaining control of Western Slavonia. Three weeks later, following a deadly VRS bombing of Tuzla, NATO air forces bombed VRS positions. In retaliation, the VRS took several hundred UN peacekeepers hostage, casting a harsh light on the UNPROFOR’s vulnerability. In early July, the VRS assaulted the enclave of Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia, capturing it on July 11, 1995, despite the presence of several hundred UN Dutch peacekeepers. In the following days, the Serb forces systematically massacred some 8,000 Bosniak prisoners, turning ethnic cleansing into genocide. On July 25, the VRS also captured the neighboring enclave of Žepa. The capture of the two enclaves of Srebrenica and Žepa strengthened the Serb leaders’ feelings of invincibility and impunity, but UNPROFOR’s helplessness to prevent the worst massacre of the war incited Western leaders to take the gloves off. In August 1995, the Croatian Army launched a general assault against the “Serb Republic of Krajina,” wiping it off the map within a few days and causing 300,000 Serb refugees to flee. Soon thereafter, deadly shelling in Sarajevo triggered a NATO air campaign to bomb the VRS’s positions. The Croatian and Bosnian armies took advantage of this campaign to break through Serb lines and recapture considerable territory in western Bosnia (see Map XII). At that time, the “Republika Srpska” was on the verge of collapse, with heightened tensions between representatives of western Bosnia and eastern Bosnia, and an open conflict between its political and military leaders. The “Republika Srpska” had to accept a general ceasefire and give Slobodan Milošević authority to start new peace talks in its name. In late October, the VRS controlled only half of Bosnian territory—i.e., what the Contact Group’s peace plan allocated to it.

While summer 1995 saw the Serb nationalist project collapse, it was also a difficult period for the SDA’s leaders. On the one hand, the fall of the enclaves of Srebrenica and Žepa created strong tensions within the Bosniak community. On the other, the SDA chose to adopt several controversial constitutional reforms during this agitated period. On August 3, despite opposition from the civic parties, it brought up for parliamentary vote a constitutional amendment whereby the Chairman of the Collegial Presidency would no longer be chosen by his peers, but by the Parliament itself, thus ensuring de facto that this position would always be held by a Bosniak. At the same time, the SDA had a law passed that clarified the competences of the federal and republican governments, reducing the latter’s prerogatives. Prime Minister Haris Silajdžić protested, with support from the civic parties, and threatened to resign. In Silajdžić’s view, the Federation was the foundation for the future reintegration of Bosnia-Herzegovina; and thus a step towards a full restoration of republican institutions. On the contrary, for the SDA’s leaders, establishing the Federation entailed a transfer of powers that had previously been devolved to the Republic, and must not under any circumstances hamper the political practices that enabled the SDA to maintain its hegemony in the ARBiH-controlled territories. For the SDA’s leaders, the Federation was nothing more than a means for the SDA to continue to assert its political hegemony over a portion of the territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina, without explicitly having to renounce its territorial integrity.

Map XII Frontlines in Bosnia-Herzegovina (April 1994–October 1995).

As the situation was changing rapidly on the ground, new peace talks opened in September 1995 under the leadership of US emissary Richard Holbrooke. These talks quickly yielded two intermediary agreements on the future institutions of Bosnia-Herzegovina. In November, the final phase of talks was held in Dayton, Ohio, leading to the signing of several agreements on November 21. Known collectively as the Dayton Agreement, these accords transformed Bosnia-Herzegovina into a state made up of two separate entities: the Federation (51 percent of Bosnian territory53) and the Republika Srpska (49 percent). The latter ceded most of the suburbs that it held in the Sarajevo region, but kept control of many towns that had had Muslim majorities before the war, including Srebrenica (see Map XIII). The status of the municipality of Brčko, considered highly strategic by both the Republika Srpska (for its territorial continuity) and the Federation (for access to the Sava River), would be decided at a later date. The shared institutions of Bosnia-Herzegovina would be a three-member Collegial Presidency, a bicameral Parliament, and a government with very limited powers. Each entity would have its own Constitution and armed forces and could establish special relations with the neighboring states of Croatia or Serbia.

In parallel, the Dayton Agreement called for elections to be organized rapidly, with refugees supposed to vote in the municipality where they had lived before the war and being granted a right to return. An Implementation Force (IFOR) made up of 60,000 men was formed and placed under NATO command, and a High Representative was appointed to oversee the implementation of these peace agreements. On November 29, 1995, only thirty-five out of 240 deputies attended the Bosnian Parliament session called to vote on this agreement. Two weeks later, on December 14, 1995, the Dayton Agreement was officially signed in Paris by Slobodan Milošević, Franjo Tuđman, and Alija Izetbegović.