After Chapter 2.5, you will be able to:

Modern theories of object recognition assume at least two major types of psychological processing: bottom-up processing and top-down processing. Bottom-up (data-driven) processing refers to object recognition by parallel processing and feature detection, as described earlier. Essentially, the brain takes the individual sensory stimuli and combines them together to create a cohesive image before determining what the object is. Top-down (conceptually driven) processing is driven by memories and expectations that allow the brain to recognize the whole object and then recognize the components based on these expectations. In other words, top-down processing allows us to quickly recognize objects without needing to analyze their specific parts. Neither system is sufficient by itself: if we only performed bottom-up processing, we would be extremely inefficient at recognizing objects; every time we looked at an object, it would be like looking at it for the first time. On the other hand, if we only performed top-down processing, we would have difficulty discriminating slight differences between similar objects. This distinction is also partially responsible for the feeling of déjà vu described in the introduction to this chapter: when we believe we are experiencing something for the first time, we expect to rely on bottom-up processing; however, when the mind finds that it is able to recognize an experience more quickly than expected (through top-down processing), it searches for a reason for this recognition. In other words, déjà vu is often evoked when we have recognition without an obvious reason: I know that guy from some where . . . but where? The distinction between top-down and bottom-up processing is relevant for all senses, but is most commonly applied in the context of vision.

Perceptual organization refers to the ability to use these two processes, in tandem with all of the other sensory clues about an object, to create a complete picture or idea. Most of the images we see in everyday life are incomplete; often, we may only be able to see a part of an object and must infer what the rest of the object looks like. By using what information is available in terms of depth, form, motion, constancy, and other clues, we can often “fill in the gaps” using Gestalt principles.

Depth perception can rely on both monocular and binocular cues (processes that involve one or both eyes, respectively). Monocular cues include the relative size of objects, partial obscuring of one object by another, the convergence of parallel lines at a distance, position of an object in the visual field, and lighting and shadowing. The primary binocular cues are the slight differences in images projected on the two retinas and the angle required between the two eyes to bring an object into focus.

The form of an object is usually determined through parallel processing and feature detection, and the motion of an object is perceived through magnocellular cells, as described earlier. Constancy refers to the idea that we perceive certain characteristics of objects to remain the same, despite differences in the environment. For example, we perceive a white piece of paper as essentially the same color whether it is illuminated by fluorescent lights, incandescent bulbs, or sunlight—this is called color constancy. We also have constancy for brightness, size, and shape, depending on context.

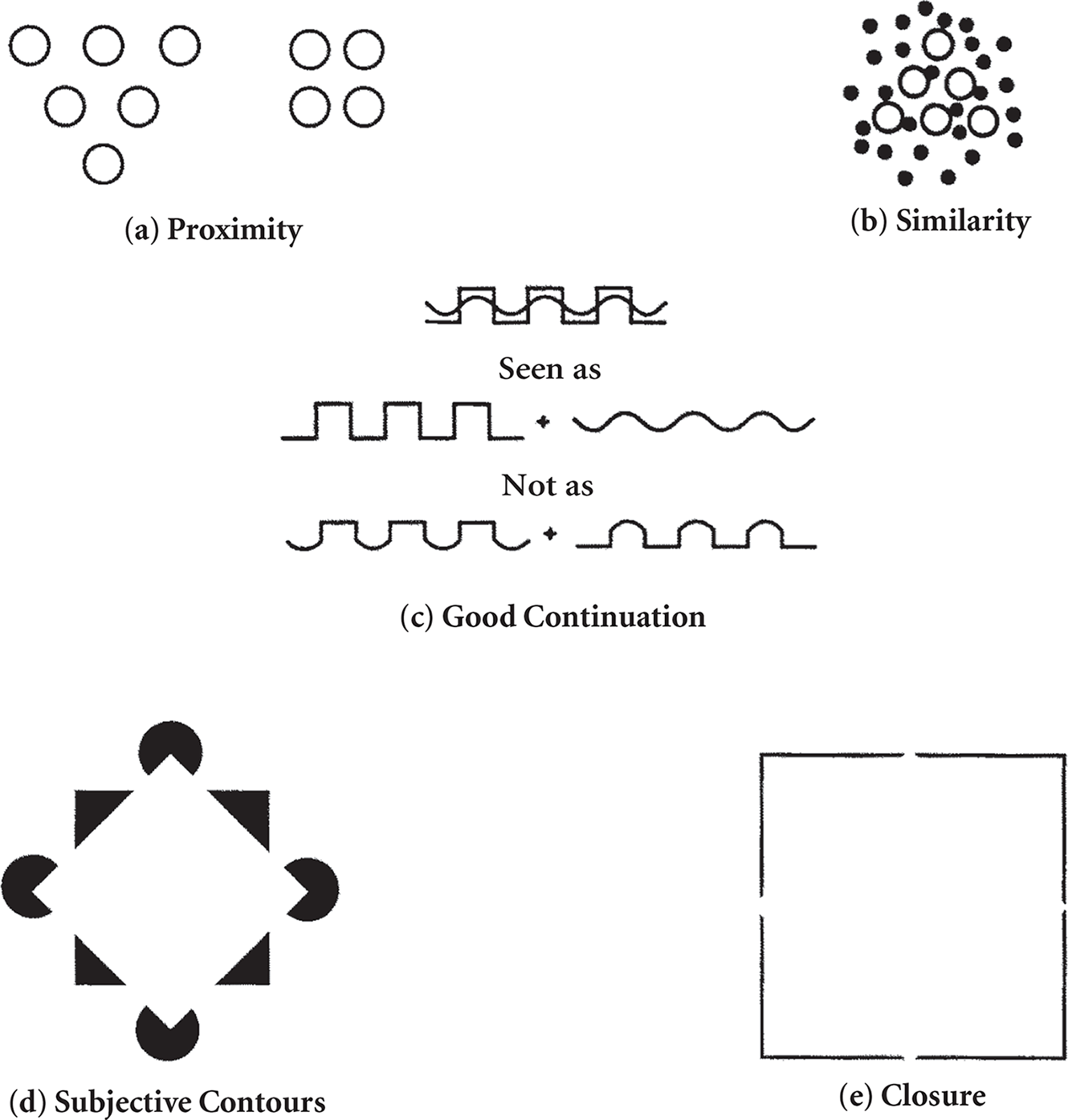

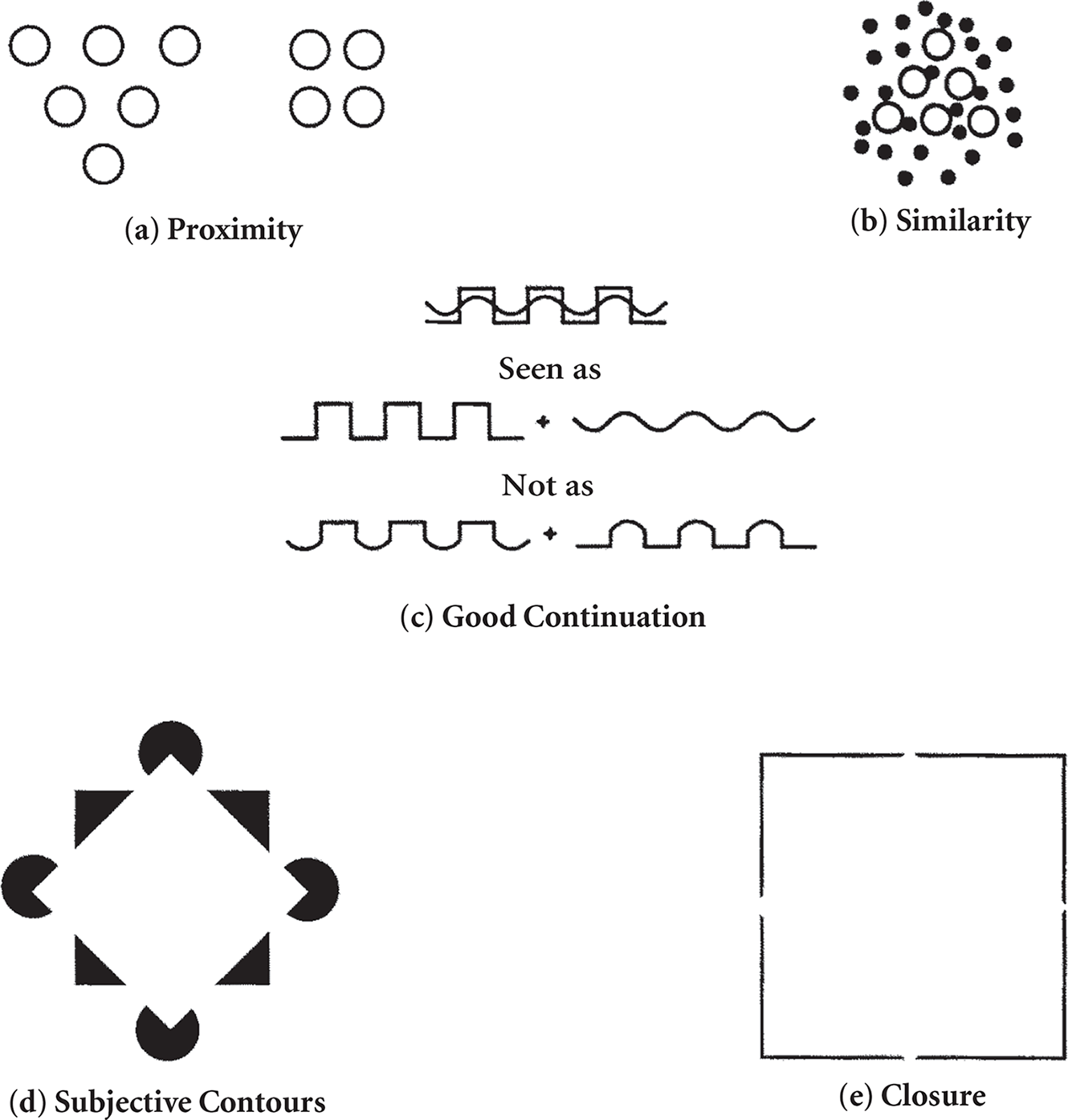

Gestalt principles generally follow the same basic idea: these are ways for the brain to infer missing parts of a picture when a picture is incomplete. There are dozens of Gestalt principles, but the highest-yield are summarized below and can be visualized in Figure 2.11.

The law of proximity says that elements close to one another tend to be perceived as a unit. In Figure 2.11a, we do not see ten unrelated dots; rather, we see a triangle and a square, each composed of a certain number of dots. The law of similarity says that objects that are similar tend to be grouped together. In Figure 2.11b, we see the big hollow dots as being distinct from the others, forming a triangle against a background of small filled-in dots. The law of good continuation says that elements that appear to follow in the same pathway tend to be grouped together. That is, there is a tendency to perceive continuous patterns in stimuli rather than abrupt changes. As seen in Figure 2.11c, our mind tends to break down this complex figure into a sawtooth line and a wavy line, rather than two lines that contain both sawtooth and wavy elements. Some researchers have argued that the phenomena of subjective contours may arise from this law. Subjective contours have to do with perceiving contours and, therefore, shapes that are not actually present in the stimulus. In Figure 2.11d, subjective contours lead to the perception of a white diamond on a black square with its corners lying on the four circles. Finally, the law of closure says that when a space is enclosed by a contour it tends to be perceived as a complete figure. Closure also refers to the fact that certain figures tend to be perceived as more complete (or closed) than they really are. In Figure 2.11e, we don’t see four right angles; instead, we see a square, even though the four sides aren’t complete. All these laws operate to create the most stable, consistent, and simplest figures possible within a given visual field. Taken altogether, the Gestalt principles are governed by the law of prägnanz, which says that perceptual organization will always be as regular, simple, and symmetric as possible.