15

Learning by doing

Memoryscape as an educational tool

I have long been excited by the potential of memoryscapes, a term I originally applied to multi-media, oral history–based experiences designed to be undertaken in specific places. Creating a typical memoryscape requires a working knowledge of a range of practical skills including applied historical research, interviewing, digital recording, sound editing, creating websites and interactive maps, and developing an understanding and critical appreciation of user-friendly tour and trail design.

This chapter will explore the learning potential and some of the practical and pedagogical issues I have encountered in training and mentoring students in the construction of memoryscapes. I have been running courses on this theme for ten years in East London with a range of participants, from teenage youth groups to postgraduate students at Master’s level, including some over retirement age.

The courses were all taught from the field of history and heritage studies in the United Kingdom, in a period of profound change in higher education. In the last decade there has been increasing pressure for degree programmes to deliver vocational skills and improve student employability.1 Combined with the digital publishing and information revolution, many history programmes now provide applied digital skills training alongside the traditional research, critical thinking, and essay and report writing. The public-facing nature of web-based work is also ideal for showcasing student’s achievements and the best projects were promoted on university and research centre websites.

Such a course could just have easily been part of a geography or creative media programme or used in an adult education or community development context. With this in mind, I hope this chapter might be useful for trainers, teachers, and lecturers interested in using memoryscapes to help students explore issues around place, public history, oral history, and local history; and along the way develop and apply skills in creating accessible and engaging digital multi-media.

My main aim is to share a range of experimental, exciting, and hopefully inspiring student project work, which, in the field of history at least, so rarely sees the light of day in academic publishing. Alongside this, I also give some context to the trails and give a sense of the nature and development of the courses that brought them about. This chapter is best read with a web browser to hand, so you can follow the links in the footnotes to the various websites and explore the work discussed.

My first attempt at a memoryscape building course was a free public workshop programme entitled Making Community History Trails focused on the communities around the Royal Docks in East London in 2007. The aim was to give local people the opportunity to develop multi-media and research skills and be involved in the creation of several artist-led trails around the docks (Figure 15.1). The aim of the project was to map and interpret something of the community history of North Woolwich and Silvertown, two communities that had been hit hard by the closure of the docks in the 1980s (Ports of Call 2008).

The programme attracted several older members of the community who were invaluable in helping us understand the historical geography of a deindustrialised area that had undergone an extraordinary amount of change. A community mapping day, in which photographs and memories were attached to a large map alongside talks on local history, planning, and mapping was particularly successful, as was a workshop on tour guiding (with increasing tourist interest in the locality following the success of the London 2012 Olympic Games bid). But it proved difficult to attract many attendees to skills workshops in digital recording or Google mapping, and in the end workshop participants featured in the trails as interviewees rather than participated as interviewers. On reflection a public workshop programme was perhaps too loose an organisational structure for sustained engagement; later projects had much more success with overtly recruiting volunteers with a clear written understanding of how much time would be expected to attend a training programme and work on project tasks. However, the open activities attracted a number of key members of the local community who were invaluable in helping the project staff to better understand the local history and politics of the dock communities.

The issue of authorship and control is intrinsic to any community project involving professional workers (composers, artists, digital producers, academics).2 There are two quite distinct forces, or tensions, that run through projects that have public-facing media as the outcome. The first is the over-arching desire to produce something that is the best possible quality – it might not be broadcast standard, but it needs to be understandable, legible, and usable by someone unfamiliar with the project. In publicly funded projects like Ports of Call there is necessarily pressure on project managers and professionals involved to make the outcomes as accessible as possible, and those with extensive media expertise are often highly adept at producing content that works in terms of a comfortable and engaging listening experience. But there is also the knowledge expertise, energy, desire, and enthusiasm of volunteers to draw upon, which may not be aligned to the intended project objectives, but may well help the memoryscape become more grounded and meaningful.

The project manager must be mindful that usually the power relationship is heavily stacked in the artists or producers’ favour – they have the technical expertise and often a very clear idea of the achievable form of the final product, particularly if the project is short term with a detailed budget, dreamed up months or even years before in a funding application. In initial meetings with community workers and potential volunteers, the intended scope of the product (the memoryscape) is naturally explained, perhaps with examples from other projects. The problem is how to build in enough genuine flexibility and scope for the local experts – usually volunteers and unpaid interviewees – to shape and participate in the project in ways that meet their own desires and aspirations. Without this the memoryscape might be technically impressive but have no meaningful heart or soul in terms of the community it is situated in (and should ideally serve in some way).

In these terms the Ports of Call workshop programme was not terribly successful – it engaged with some community members and established some relationships, but had a relatively shallow impact in terms of volunteer engagement with the trail production process, and two of the trails were ultimately heavily artist-led in terms of choice of content.

In this regard we had much more success with the Asta Trail, delivering a workshop programme for an existing youth group of 11 to 17 year olds. They met at the Asta Centre, a small youth centre after school in Silvertown in the shadow of London City Airport that had both a small recording studio and Jason Forde, a talented and enthusiastic youth worker with DJ mixing skills who used the studio for music recording and editing workshops. This meant we could run a more focused workshop programme from the Asta Centre in the heart of Silvertown rather than at the University of East London, and the three-hour sessions ran almost every evening over a two-week period in the summer holidays.

It also soon became clear that finding out about local history was going to be a tough to sell to a diverse group of young people; but there seemed to be a very strong desire to learn any skill that would be required to make rap music. Jo Thomas, a composer and university lecturer brilliantly built up the workshop programme around this interest and worked on lyric writing and multi-track recording, composition, and editing over two weeks in the summer holidays. A walk around the area with the young people revealed an array of issues that concerned them, ranging from fear of gangs in neighbouring communities to anger that a graffiti mural they had painted with a community artist was going to be removed by the council following a complaint by a local resident. Their concerns inspired their rap lyrics and composition that later featured very prominently in the trail.

After some training in recording and interviewing, the young people also recorded interviews with local experts including a property developer, museum curator, an airport representative, and the owner of the local grocery store. This led to some really interesting opportunities for the young people to question people who were prominent in the community (and in turn the interviewees had the opportunity to hear some of the current concerns from a younger generation).

The Ports of Call project was my first adventure in community-based project work. The project highlighted a number of engagement issues. The most successful work came from engagement with existing groups, brokered with experienced community workers who already had the trust of the young people concerned. This was not without difficulties; the summer period meant that some of the group left for holidays, or drifted away to do other things, leaving a core of a few young people to help Jo in the latter production stages. Some had moved to London from other countries recently, and we quickly realised that some who seemed quiet or reticent were actually coping with English as a second language. At times the issue of power and control over content had to be sensitively but overtly negotiated; some violent language and lyrics around gun crime made a great track for teenagers in a youth centre, but eventually were dropped by discussing their relevance to the locality and thinking more deeply about the potential audience – which included parents and carers.

However, the material was not all ‘safe’; for example, critical content over the issue of the mural erasure was retained. The result was a rap song and interview material that entwined the present and future in a memoryscape around Silvertown entitled the Asta Trail: Planes, Trains and Graffiti Walls and some of the interview material was used in a another trail Jo constructed in West Silvertown (Asta Centre & Thomas 2008; Thomas 2008). The trails were put on to 1,000 CDs (Figure 15.2) and given away to community groups, local residents, and newcomers to the area. Brenda Ridge, one of the participants who had put days of effort into singing and song writing, featured on the CD cover, and the group all received MP3 Players as a reward for their work and were collectively acknowledged as co-authors (Asta Centre & Thomas 2008).3

Two years after the Ports of Call project I had an exciting opportunity to develop a course from these experimental workshops in partnership with Birkbeck College, a co-partner in the Raphael Samuel History Centre.4 Birkbeck is well known for providing flexible and part-time courses for adult learners and there was a good fit with the ethos of the University of East London. The Centre was keen to jointly develop innovative history courses and events that might attract students to both institutions. At Birkbeck Mike Berlin taught London history and used both historical maps and walking as teaching methods; he was an ideal match to complement my experience in teaching oral history and digital media. The course we devised was entitled Exploring London’s Past: Archives, Architecture and Oral History, part of Birkbeck’s Certificate in History programme, a pre-undergraduate programme which accepted mostly mature applicants, some with few or no qualifications. Mike gave talks on the politics of heritage, specifically of twentieth-century London, and used maps and archives to research London history. I spoke on the theory and practice of walking trails, cultural geographies, and mapping experiences. In the final week students presented their proposals and their work in progress. I also gave practical workshops in oral history recording, sound editing, and Google map making.

The coursework assignments were to provide a short, 500-word trail plan, to include potential archives, locations, and interviewees; followed by a digital project – a Google map, website, or documentary equivalent. We asked that this should contain:

- written material on at least three locations, including references to sources;

- at least one oral history excerpt, either from an archive or recorded by the student;

- an image for each location; and

- a reflective account of around 800 words on the theoretical, artistic, and practical justification for the trail design (locations, content, what the trail aims to achieve).

For some students used to conventional, essay-based assessments, this was a forbidding assignment. It was important to be up front about the demands of the assessment in the course description and we found that students needed regular reassurance and where necessary technical support. We also made it possible to submit an almost entirely paper-based assignment for those who struggled with the web-based media. More user-friendly iterations of digital map and web platforms such as Google Maps, ZeeMaps, WordPress, and Wix.com have made matters much easier. It also helped to show and experience examples of memoryscape-based work; this was easier in later years as student projects could be used for inspiration and as a reassurance that a similar project could be created in the time allowed.

Many students focused on the local history of London’s suburbs, far away from the more usual guided walks and tours around central London. Linda Davies took her home community, South Acton, and teased out hidden histories from her own memories and knowledge of how the locality had changed. She mapped lost laundries (of which there were once over 200), converted pubs, and demolished streets. In her reflective account she explained that she found two approaches particularly useful in focusing her work; the first was to ‘walk around the map mentally to see which locations suggested absences or memories’; the second was to use a more playful, surrealist approach that we had explored in the course, based loosely on Walter Benjamin’s Convolutes method of using an A to Z list of keywords to provoke thought about specific aspects of place (Davies 2011a). Her experimental map, which is colour coded by historic period, included interview recordings with local people including her mother who had lived through the Blitz. This has now had over 2,200 views, impressive for a student history project (Davies 2011b).

Perhaps the most impressive of these early experiments in terms of scale was 47 Bus: a linear history project by Jonathan Bigwood. Jonathan had worked professionally, producing public transport information, and he was struck by the way that a London bus route was largely unchanged for almost a century. He explored the idea that the bus route linked people and places historically, as well as geographically:

The project was astonishingly ambitious; the original bus route ran from Farnborough near Bromley on the edge of suburbia in South London and took around 90 minutes to go through numerous communities until it reached Shoreditch in central London. Jonathan incorporated hundreds of points of interest, many with links to relevant websites, recordings, and newsreel clips, and eventually decided to create three maps; one is focused on transport history with historical routes mapped alongside 145 transport-related points of interest, another devoted to relevant voices, sound recordings, and film (from online archives), and a final ‘other history’ map with a further 93 points of interest, mostly focused on noteworthy buildings, markets, parks, and housing estates along the route (Bigwood 2011). This work demonstrated the potential of Google Maps for people to share histories, not just of their local communities but of routeways and networks that shape our understanding of places too. At the time History Pin was in its infancy, but it has since developed into a well-established international platform for hosting place-based collections and tours. Students have also experimented with app-based trail delivery platforms such as Woices (which recently shut down).

47 Bus also began to explore the public transport journey as a potential platform to curate memoryscape experiences via the mobile smartphone. The length of the journey, the relatively low speed of the London bus, and the elevated viewing position had advantages that are well known by bus tour operators in capital cities, but the smartphone was beginning to open up the public transport network as a very cheap platform for anyone to curate tour-like or gazetteer-based experiences. A much more oral history–based bus experience was developed later by a postgraduate student, Richard Turner, who interviewed 85-year-old author and journalist Bill Mitchell (a well-known chronicler of life in the Yorkshire Dales). The recordings were made into A Daleman’s Journey, a memoryscape designed for a bus route from Skipton to Settle through the Yorkshire Dales, the bus route Bill used to take every day to get to work (Turner 2013).5

Postgraduate trails: place, oral history, and digital heritage

The following year (2012) the Raphael Samuel History Centre launched a new MA entitled Heritage Studies: place, memory and history.6 The programme was designed to take a broad and inclusive approach to heritage, embracing the street and the internet as much as the museum and gallery, and give students the opportunity to develop digital skills and practice-led research projects. I led the programme and developed a core module that would explore the relationship between heritage, memory and place (particularly in relation to the urban and post-industrial landscape of East London). The module considered how places are conserved and ‘made’ in terms of popular memory, heritage, and artistic and historic interpretation. A more ambitious memoryscape assignment was designed to give students hands-on experience of researching and producing historical material for a public audience. Students came from a variety of disciplines, so the course also had to ensure that students developed appropriate skills in historical research, oral history recording, sound editing, web page design and considerations of audiences and accessibility.

The module was taught over 12 three-hour sessions followed by a three-week production period for students to work on their final projects. The assignment ran along similar lines to the History Certificate course detailed earlier with a web-based memoryscape project, but this time it had to be accompanied by a much more demanding 2,000-word reflective essay, with instructions that it should be a theoretical, artistic, and practical justification for the trail design and methodology and refer to examples and relevant literature to situate the work. The course covered theoretical and artistic ideas and case studies relating to the cultural geographies of place alongside skills workshops and field trips to experience and consider specific memoryscapes as a group. The challenge of providing the range of skills and expertise necessary for multi-media practice was helped enormously by involving UEL colleagues who could support the course with practice-led experience.7

Over the years, students experimented with app-based platforms for their project work. Students have also experimented with app-based trail delivery platforms such as Woices (there are dozens of others), although the latter recently shut down. Using any free platform has an element of risk in this regard, so we taught well-supported website services that stood most chance of survival (e.g. WordPress; Google Maps), and as a result most student websites have survived and are still operational at the time of writing (early 2018).

The involvement of the Rix Centre was invaluable in terms of exploring some of the major accessibility issues inherent in both walking trails and online and mobile platforms. The Rix Centre was established in 2001 as a charity based at UEL to develop new technologies to transform the lives of people with learning disabilities. They had already developed the RIX Wiki platform, an online website authoring tool specifically designed for use by and for people with learning difficulties and used by service providers, schools, local authorities, carers, and families. The ease of use made it a useful tool for our students to quickly create and gain confidence authoring online multi-media at the beginning of the module, and we hoped the accessibility issues explored in the process would be applied in the final projects to make their projects as accessible as possible. The platform itself was developed as a result of the programme, so Google Maps could be incorporated, and some students used it to deliver their entire project.

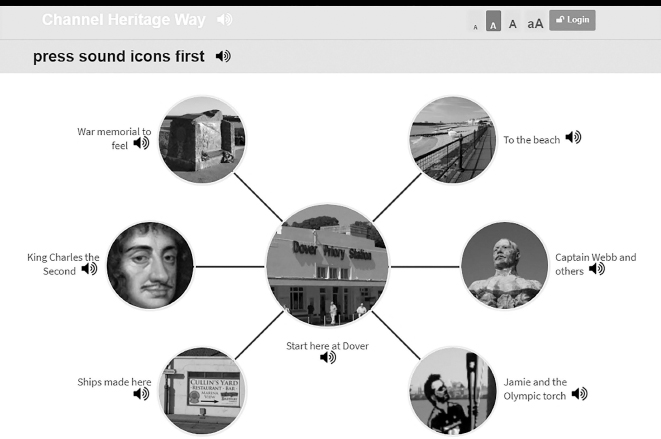

The first memoryscape devised specifically for people with learning difficulties was created by Sarah Mees for a seaside trail at Dover in Kent. Her trail Channel Heritage Way (2016) (Figure 15.3) was developed with a considerable amount of user testing on location in Dover with people with learning difficulties from the Tower Project in London. The trail incorporates a range of memorials, sculptures and statues along the seafront. The web platform is highly visual with minimal text and image led. The experience is extremely multi-sensory and the listener is encouraged to touch, feel, listen, smell, spot, and find things. The physical and sensual experience is augmented with music and video, and all elements are accompanied with audio narration.

The most sophisticated project in terms of production was the Brixton Munch (2013a) by Laura Mitchison. The trail is based in a food market in Brixton, South London, at the centre of the Caribbean community, amongst others, that settled here. Laura was influenced by Doreen Massey’s idea that places are not fixed and bound but constellations of relationships and networks, and what better place than a market, where almost everything on sale has been brought from another place, to explore how the idea might play out in terms of local heritage.

In this trail Laura moves away from using conventional oral history recordings to more crafted stories and memories co-scripted with stall holders and locals. She explains:

The process by which she does this first involves creative preparatory work to stimulate the historical imagination alongside a process of co-producing the memories she collects along with the interviewees:

The resulting stories are impressionistic rather than representational and are complemented with a superb local Rastafarian narrator, Shango. These voices are entwined with the smell, taste, music and sound relating to the foods and locations on the trail and I think very successfully capture what Laura terms ‘the magic of the place.’

Some students experimented with fictionalised elements or characterisations. Halima Kanom’s Wander East Through East (2013) of the first Chinatown in London, situated in Limehouse near the West India Docks from 1890 to the 1940s. Halima struggled to find accounts of the community from a Chinese migrant perspective, so she created an imaginary character, Chung Li, a recently arrived sailor in 1919, to imaginatively guide the listener around the old streets of Chinatown, drawing on research and archive images and oral history recordings (Kanom 2013). The most dramatic trail was created by an ex-television documentary maker, Bruce Eadie. He was an experienced interviewer but wanted a new challenge of writing what he termed ‘aural drama.’ Bruce’s approach was inspired by And While London Burns (Platform 2007), a fictionalised audio trail concerned with the financial district of London’s role in climate change by art activists Platform. He decided not use interview recordings, but create his own fictional characters to explore imagined memories of the inmates of Bethlam Royal Hospital for the mentally ill (or Bedlam as it was known, said to be the world’s oldest mental hospital). This is not strictly a memoryscape in terms of using oral history, but I include it to illustrate how dramatically the concept was pushed. He uses the device of a conversation between two characters to explore ideas of madness around Liverpool Street Station near Spitalfields, London – the original site of the hospital. His two characters are personifications of Raving and Melancholy Madness, two statues displayed at the entrance of the hospital from 1676 to 1815 personified as brothers by Alexander Pope in a vitriolic poem The Dunciad in 1743. Bruce imagines the brothers as ghostly inmates of the hospital, discussing, arguing, and raving about the history of the hospital and the perception and treatment of madness:

The resulting trail A Bowl around Bedlam with the Brainless, Brazen Brothers is imaginative and engaging, and successfully conveys a large amount of historical information alongside other symbolic and psychological dimensions to the experience (Eadie 2012).

Students were also forced to reconcile an array of ethical, participatory, and representational issues that are bound up with locational public facing work. Rosa Vilbr’s The Way Home: a walk around Hackney’s housing history (2013) drew on a collection of oral history interviews collected by a campaign group, Hackney Housing for an oral history project in 2011. The aim of the project was to ‘investigate and share personal and collective attempts to make housing better in the past. By doing this we hope to start conversations about what can be done to solve housing problems experienced today.’ Rosa’s trail includes a visit to the Hackney Service Centre, where Hackney residents came to get help from the Council with housing issues. The listener takes a seat in the waiting area and joins people queuing to see officials. The narrator explains the main principles of housing policy the officials are applying to decide who can be helped with their housing needs. This is followed by memories of the stressful interview process from those applying for council housing. It is an unsettling experience and some might feel uncomfortable in terms of the arguably voyeuristic nature of the experience. But this locational immediacy gives the memories a deeply impactful new life as you are witness the enactment of the housing politics of the present being played out before your eyes.

Another more politically orientated project by Sam Smith and Cindy Boga collected 17 interviews from the Occupy camp that had recently been established near the London Stock Exchange outside St Paul’s Cathedral. The students had to tackle complex issues of representation, both in terms of reflecting the spectrum of opinion and perspectives they discovered in the camp and more widely in terms of the how the camp would be remembered. In her reflective essay, Cindy explained:

The students set up an Oral History Working Group in the camp and established a permanent presence in the camp itself. They had to navigate challenges from other researchers over their research strategy and consider questions of access and ownership alongside the fast-moving realities of recording in a protest camp (the interviews recorded for the project were archived and made publicly accessible at the Bishopsgate Library in London). The resulting trail Occupy LSX (Figure 15.5) (Boga & Smith 2013) is a good example of how memoryscape can capture and interpret temporary and transient histories, even in the shadow of huge historical edifices like St Paul’s Cathedral that command the attention of the casual visitor.

Sam reflected:

There has not been the space to include many other impressive student projects, but I hope the range of trails discussed will inspire other educators to experiment with the medium. Creating memoryscapes is a uniquely challenging and exciting means of engaging students with place-based issues, using memories and oral histories in the public sphere and creating engaging and stimulating experiences. Over the years feedback suggests that students particularly enjoyed the variety of the sessions, the creative practice and the opportunity to develop practical multi-media skills and create something public facing. From the lecturer’s perspective it has been immensely rewarding and at times exhilarating to teach, both in sharing the creative adventure with students and in giving me the opportunity to work with colleagues from different disciplines to create a supportive and stimulating workshop environment.

References

Asta Centre and Thomas, J. (2008). The Astra Trail, Silverton. Accessed 21 December 2018, www.portsofcall.org.uk/astatrail.html

Bigwood, J. (2011a). 47 bus. Accessed 21 December 2018, https://47bus.wordpress.com/

Boga, C. (2013). A reflective essay on Occupy LSX, an audio tour of the Occupy Camp at St Paul’s Cathedral (Unpublished essay).

Boga, C., and Smith, S. (2013). Occupy LSX. Accessed 21 December 2018, http://cindyboga.wixsite.com/occupy-london-lsx

Chomsky, N. (2012). Occupy. London: Penguin.

Davies, L. (2011a). Finsbury work and play: An audio-walk around Finsbury and Shoreditch (Unpublished essay).

Davies, L. (2011b). South Acton hidden histories. Accessed 21 December 2018, http://goo.gl/maps/B9ab

Eadie, B. (2012). A bowl around Bedlam with the brainless, brazen brothers. Accessed 21 December 2018, www.flanr.net/essay/

Kanom, H. (2013). Wander east through east. Accessed 21 December 2018, http://halimakhanom41.wixsite.com/wandereast

Mees, S. (2016). Channel heritage way. Accessed 21 December 2018, https://wiki.rixwiki.org/Default/home/channel-heritage-way-clone/

Miller, L. (2011). Going places: Creating a memoryscape of Montreal. In: L. Miller, M. Luchs and G. Dyer Jalea, eds. Mapping memories: Participatory media, place-based stories and refugee youth. Quebec: Marquis.

Mitchison, L. (2013a). Brixton munch. Accessed 21 December 2018, http://brixtonmunch.wixsite.com/brixtonmunch

Mitchison, L. (2013b). An audio tour of food stories in Brixton market: Reflective essay. Accessed 21 December 2018, http://brixtonmunch.wixsite.com/brixtonmunch/essay

Platform. (2007). And while London burns. Accessed 21 December 2018, www.andwhilelondonburns.com/

Smith, S. (2013). A reflective essay on the creation and testing of the Occupy LSX audio trail: Virtually re-occupying London Stock exchange (Unpublished essay).

Thomas, J. (2008). The West Silvertown Trail. Accessed 21 December 2018, www.portsofcall.org.uk/westsilvertown.html

Turner, R. (2013). A Daleman’s journey. Accessed 21 December 2018, www.rixwiki.org [login with username: Billmitchell and password: Bill].

University of East London. (2008). Ports of call. Accessed 21 December 2018, www.portsofcall.org.uk

Vilbr, R. (2013). The way home: A walk around Hackney’s housing history. Accessed 21 December 2018, https://hackneyhousingtour.wordpress.com/about/