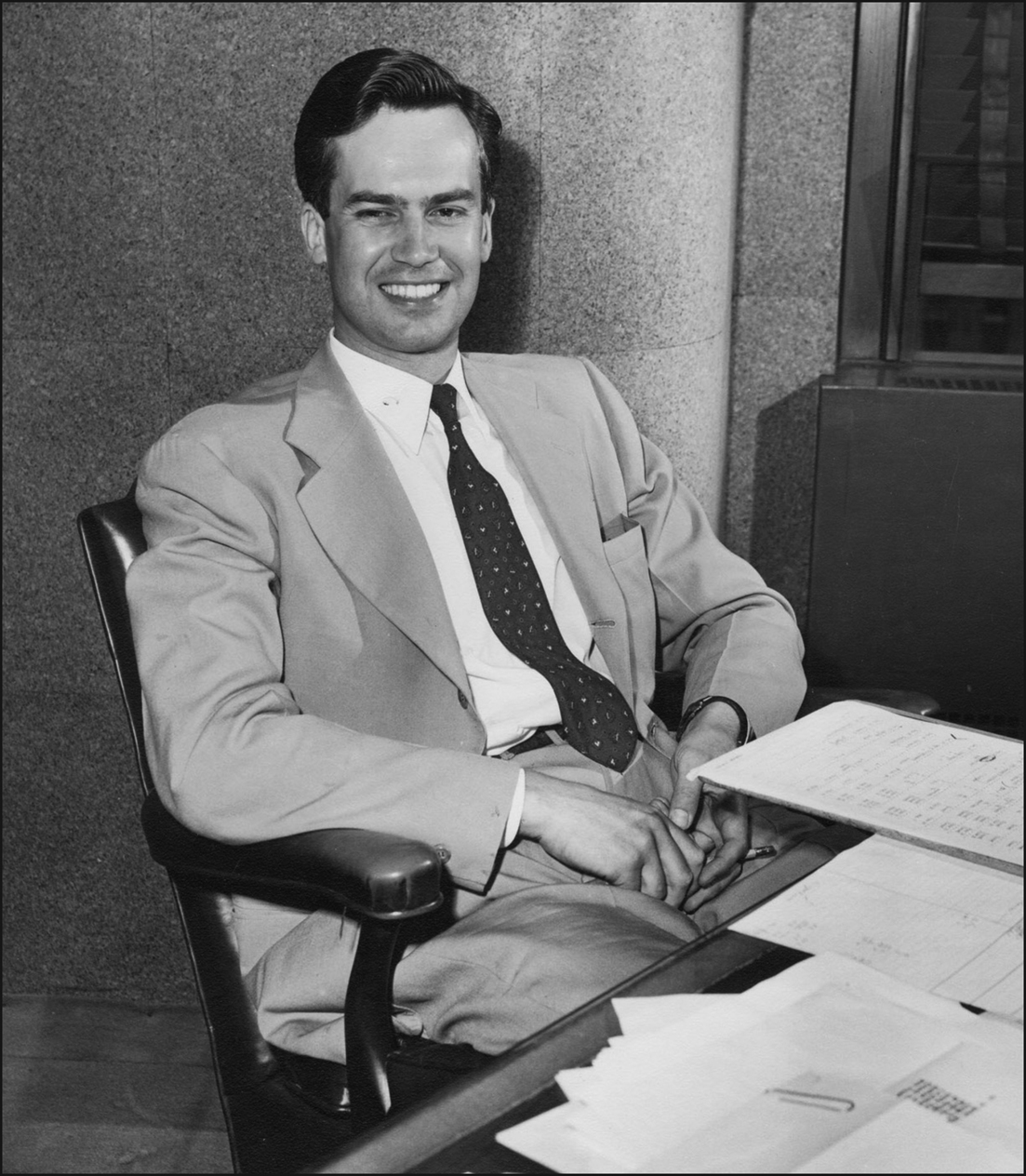

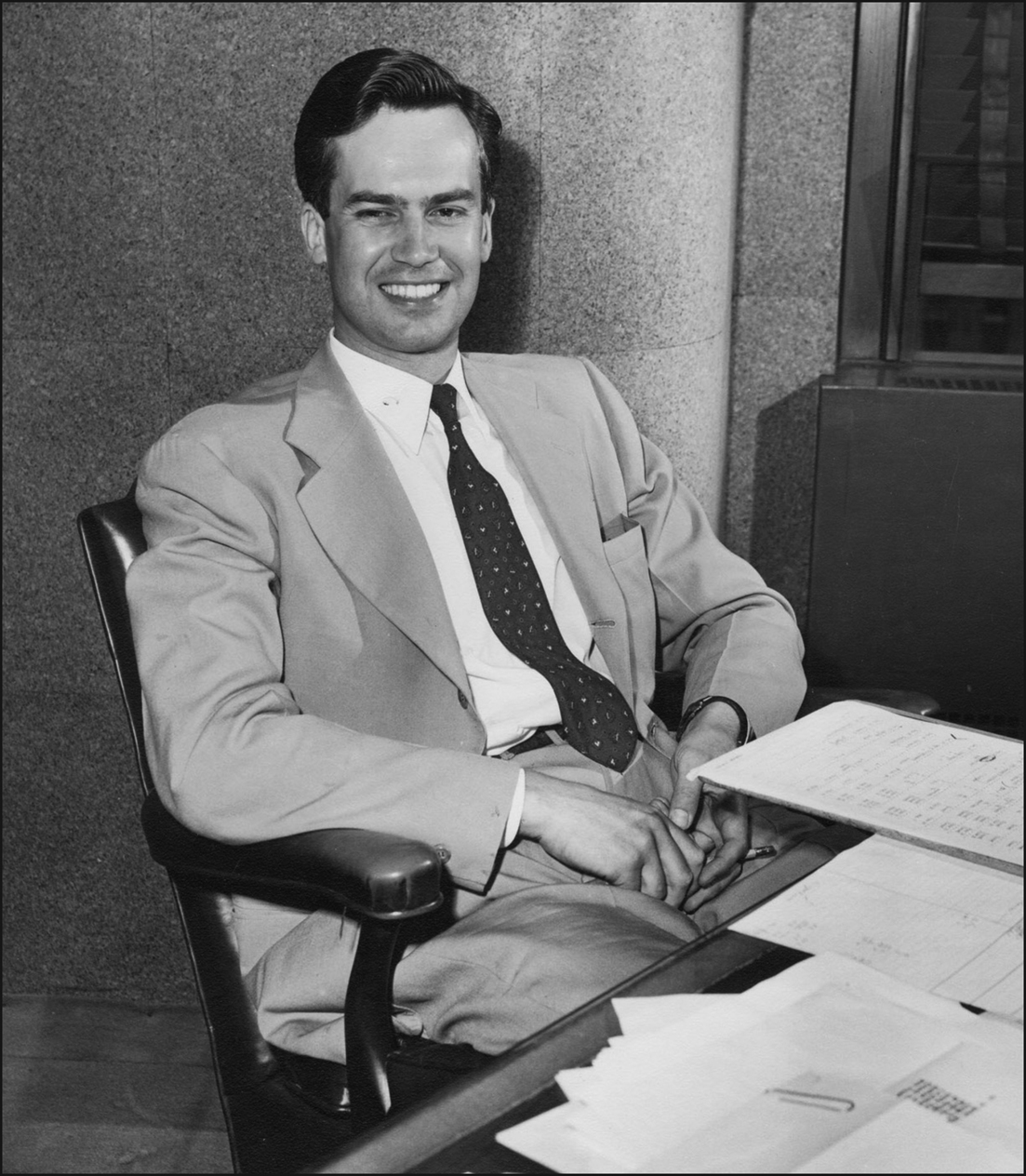

Joe Thorndike at his desk at Life, July 11, 1947. Photo by Bill Sumits, courtesy of Life Photo Archive, Time Inc.

Sometimes I wonder what it would be like if I were looking instead after my elderly mother, if she’d been the one to survive and come down with Alzheimer’s. I’m sure we’d have talked with far more intimacy than I can wrest from my father—but I can also imagine how needy and difficult she might have turned. She never had my father’s restraint and equanimity. Of course, there’s no knowing when Dad might go awry himself. No matter his natural reserve, no matter how gentle and decent he has always shown himself, such character traits are no match for this disease, or so I’ve read. Once the brain is colonized by Alzheimer’s, all moderation can fly out the window, and the mildest-mannered patient become hopelessly irascible.

I register this, yet hold onto the belief that my father will be different, that his lifelong nature will prevail. It has so far. Occasionally he panics a little, but I see no sign of bitterness or anger. It seems to me the disease would have to reach his very brainstem before it could wipe out his essential decency.

Young Joe, as my father calls him, has arrived for a visit. Like Dad, he’s a historian. He’s been finishing his dissertation on FDR’s tax policies, and is about to earn his PhD. Dad hoped he would bring his two-year-old daughter Eliza, but the trip was too long and the girl too wild, so Joe has come alone. Dad’s happy to see him, but also confused. I think he’s reminded of our August reunions, because now he’s convinced that the rest of the family will soon arrive.

Joe, the only cook among the brothers, prepares a cioppino filled with clams, shrimp, scallops and cod. Dad shines at the dinner table, and after the meal he remains alert. He talks about his parents and about working for Henry Luce at Time. He makes suggestions about an article Joe wants to write, and tells of a novel he wants to write himself, about two men fighting for control of an uninhabited island in the Pacific. Tonight he still has ambitions.

I’ve told Joe many stories of Dad’s confusion, and he’s seen the signs himself. But now our father is talking like a professor about the policies of Wilson, Hoover and Roosevelt. It’s Joe who brings this out, I’m sure. They are the intellectuals of the family, as was Joe’s mother. I was twenty-three when Joe was born, so we spent little time together when he was young. More in recent years, though, and not long ago we shared a pair of odd confessions. Joe told me that he’s always felt that Al and I have been closer to Dad than he has, and I said that I’ve long thought of him as my father’s truest offspring, the one who can get Dad to talk. Of course, our father would never show or confess to the least favoritism toward any of us—but it’s Joe who has him talking tonight. I’m happy about this, glad to see him come out of his shell.

The next morning he’s agitated. He wants to go outside, no matter that rain is sweeping across the driveway. He parks his walker in front of the door, stares out at the drowned morning, then announces to me and Joe that he wants to look around in the sunroom, an enclosed but unheated space. His two oversized file cabinets are out there, and I clear away some of my tools so he can reach them. He’s wearing his coat and hat, I plug in an electric heater, and the cold doesn’t seem to bother him. Indeed, he barely notices me. He’s standing in front of the far cabinet, lifting out pieces of paper, fingering them and putting them back. Later he pulls a chair over, sits down on it and begins to explore one of the lower drawers.

As I watch from the kitchen, my tenderness for him grows. He pulls out one sheet of paper after another, inspects them in the solemn way of a young child who has not yet learned to read, and returns them to their folders. He spends almost an hour at this, and eventually asks me to bring all the papers from that drawer into the living room. I transfer them into a cardboard box, set the box on the coffee table, and that evening, as Joe cooks dinner, I start to look through the papers myself.

The very first sheet, lying on top, is a 1948 memo to my father from Henry Luce, with his comments on an article Malcolm Cowley was writing about Ernest Hemingway. In the forties my father worked with many well-known writers of the time, including John Kenneth Galbraith, John Dos Passos, Whittaker Chambers, James Thurber and Winston Churchill.

He worked with all the early photographers at Life as well: Peter Stackpole, Margaret Bourke-White, Dmitri Kessel, George Silk, Nina Leen, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Milton Greene, Philippe Halsman, Robert Capa, Gjon Mili, Carl Mydans and many others.

I’ve been aware since I was a teenager of his connections to famous people—though by the late fifties, at American Heritage and Horizon, he was working with writers better known in academic or artistic circles: the historians Bruce Catton, J. H. Plumb and H. R. Trevor-Roper, along with Irving Stone, William Harlan Hale, Walter Kerr and Ben Shahn.

Although I know their names, Dad has never told me stories about any of them. He doesn’t gossip and never says anything about what interests me most, the people he worked with. I know that when Churchill came out with The Gathering Storm, the first of his volumes about the war, Dad helped him distill the book into six long excerpts, which were published in Life in successive issues in the spring of 1948. But now, when I ask him for stories about Winston, there’s not much he can tell me.

Joe Thorndike at his desk at Life, July 11, 1947. Photo by Bill Sumits, courtesy of Life Photo Archive, Time Inc.

“Did he come to your office,” I ask, “or did you go to where he was staying?”

A pause. “I think he must have come to the office.”

“And was he helpful?”

“Quite helpful. He was—quite helpful. He did like to drink.”

“You mean he was drunk?”

“No, I wouldn’t say that.”

His answers are rarely specific, perhaps because he can’t remember. I’ve waited too long to ask my questions, and now no one from those years is still alive. Every one of the writers and photographers named above is dead. Henry Luce is dead, and his wife Clare Booth Luce, and the two managing editors at Life who preceded my father, John Shaw Billings and Dan Longwell. Dad, I believe, is the last survivor from the magazine’s early years.

Why, I ask myself now, didn’t I come and spend a month with my father when he could still hold a conversation? Even a year ago I could have learned plenty if I’d asked him more questions. Instead I trundled along, too busy with my own life. I never went to visit him in Maine, or to Florida in the winter, and when I came to the Cape I threw myself into everything except these files. Dad would have shown them to me gladly, I think, but I never asked. We’re all warned about this: Better ask the questions while you have the chance—and I didn’t.

I think of my father when he was young, the beloved child of an older couple, a solitary boy with not enough friends. He rose through ambition and the power of his mind, and lived a broad intellectual life at the center of the publishing world—yet he was always devoted to his family. He could talk to Winston Churchill during the day, then come home on the 6:12 train with presents for his boys. On Saturday morning he’d crouch on the lawn and renew his ancient battle with the crabgrass, and watch over us as we swam.

Few old people remain connected to the channels of power and fame. I think of our most famous Alzheimer’s patient, President Reagan, in the final years of his life, getting up in the morning, eating breakfast, taking a walk around the grounds. It’s what most of us come to in the end: we have our family and friends, we have our children, we cultivate our garden. I’ve always believed in simplicity, and still claim not to care about a dramatic, more exciting life—but consider my fascination with the people my father knew and worked with. Money, fame, power and involvement: I’d love to have more of it all.

I’m steadily surprised—as is my brother Joe—at how relaxed Dad is about being naked. He doesn’t react at all when I come into the bathroom to check up on him. He’ll sit on the toilet, pissing slowly, or stand like a jaybird in front of the shower, unaware of his body or unconcerned about it.

I asked the head of one of the dementia units I visited last month if this change in modesty was common. “Oh, sure,” she said. “That all fades away. I could run a completely nude unit here and none of them would care.”

My father, who seems so independent, has hardly spent a year alone since 1939. Soon after his painful divorce from my mother he courted and married Margery Darrell, an editor at Horizon. Joe Jr. was born in 1965 and grew up with Margery’s two sons by an earlier marriage. After ten years Dad and Margery separated, and I thought he would retire from the world of romance. Instead he met Jane.

Jane had her demands, but they were easy for my father to meet. She liked attention. She liked to be looked after, and Dad was good at that. Born to serve, Al and I used to joke, after watching him take care of everyone he loved—including us.

In recent years, as Jane’s health declined, my father spent more and more time with her. Though he didn’t sell his house on the Cape and move in with her in Connecticut, as she wanted him to do, he stayed there for weeks at a time, running errands, cooking meals and answering her frequent calls. Her family had hired some women to help, but only my father would do. “I want Joe,” she repeated, and though by then his own health was giving out, he did his best.

Given their long history I find it bizarre that Jane, who died with millions, didn’t leave my father a dime. I asked Dad about it only once. “No sense worrying about that,” he said, and the subject was closed.

And the fact is that for almost thirty years Jane paid my father in another coin. She was spoiled, but she was also lively and fun, exactly the blithe spirit my father loved to be around. She brought out a side of him my brothers and I rarely saw. Two Christmases ago in Vermont, Al paused outside his office door to listen in on Dad, who was talking to Jane on the phone. My father has a dry and subtle sense of humor, but the laughter coming out of Al’s office was bubbly, at times almost a giggle. Dad doesn’t like to stay on the phone, but he stayed on with Jane. “It was like listening in on a teenager,” Al said—and by then Dad and Jane had been together for more than twenty-five years.

She loved a good prank. Back in the days when telegrams were delivered over the phone, she had me call her cousin and pretend to be a Western Union operator. We’d written out the message together in the archest telegram style, recounting the loss of the family silver, all gone, stolen in the night. The call raised a hell of a tempest.

Her lightheartedness, I think, was her response to some devastating blows, including the deaths of two of her brothers when she was young, and later of two nephews who committed suicide, four years apart to the day. And by far the worst, the nightmare of every parent, one of her daughters was killed in college, struck by a car at a dangerous crosswalk.

By the time she met my father, Jane didn’t want to talk about any of that. God knows how much she had grieved. But the years had gone by, as they had for my father after his two troubled marriages, and now Jane wanted to laugh and have fun. She was a smoker and a drinker, and didn’t want to talk about her calamities any more than Dad wanted to talk about his. They reached an understanding and made each other happy—which made the rest of us happy as well.

Finally a hint of spring. The ground is still covered with snow, but we’ve had our first day of forty degrees. As I opened the front door this morning I surprised a pair of mourning doves under the bird feeder. They exploded into the air and clattered away toward the trees, and just describing this to Dad brought a smile and an animated look to his face. It makes me long for the time when he can go outside and stay there comfortably, when he can watch the birds and the year’s new growth.

I’ve been reading about Alzheimer’s in David Shenk’s portrait of the disease, The Forgetting. The usual progression has been charted quite precisely, and it starts in the hippocampus. This two-inch structure, nestled deep within the brain’s temporal lobes, is what enables us to secure current thoughts and impressions as long-lasting memories. During brain development, it’s the last component to gain protective myelin, and one of the last to work effectively—which is why few people can remember much from before the age of three. It’s also the least myelinated part of the brain, and one of the first to have its myelin stripped. Thus, memory loss is almost always the first sign of encroaching Alzheimer’s.

The next part of the brain to be affected is the nearby amygdala, seat of such primitive emotions as fear, anger and craving. Slowly—it can take a decade, possibly longer—the temporal, parietal and frontal lobes will all be taken over by the gooey plaques and neurofibrillary tangles characteristic of the disease, and each step will erode some new social, mental or physical skill in the patient.

In a terrible reversal of the brain’s development, an Alzheimer’s patient unlearns everything he or she learned as a child, in almost exactly the reverse order. At one to three months a baby can hold up its head. At two to four months he can smile. At six to ten months she can sit without assistance, at a year walk without help, at two to three years control her bowels, at three to four years her bladder. The continuing progression is familiar to anyone who has raised a child: can use a toilet on his own, can adjust the temperature of bath water, can dress himself, and so on.

That’s my dad right there: he can no longer put on his clothes by himself—or if I let him, he’s likely to botch the job. Sometimes he can adjust the temperature of the bath water, and sometimes not. Ahead lies inescapable regression.

We often think of old age as a return to a kind of childhood, as a time we can relinquish many of our duties. As we grew up we learned to follow schedules and perform chores. We were told to keep our clothes on, to sit up straight, to say please, to tie our shoes and pick up our toys. We learned to make our beds, to mow the lawn, to take out the trash, to bring in the dog and put out the cat. We grew up bending to the yoke of adulthood.

But now that Dad has no dog or cat, now that I take out the trash and he’s free to do whatever he likes, a nasty trick has been played on him. He can’t relax. He’s fretful and full of compulsions. The trouble is, he’s still aware of what he’s losing.

He’s had a bad couple of days since Joe’s departure. Joe explained that he’d come back soon and bring his daughter, Eliza, but I don’t think Dad is reassured by such plans. Soon for him is a black box, and what he sees now is that Joe is no longer here.

When I get come home from the library at four he’s just getting into bed. I coax him into watching some Victory at Sea on tape, from the television show of the early fifties, but before the segment ends he’s gone. Not just asleep, but fallen off the end of the earth. His face shows no sign of rest or dreams, only a flatness that looks like defeat. I fix an early dinner and soon have it on the table, but “No,” he says when I wake him. “No dinner for me tonight. None.” He’s so definitive about it I take his plate back to the kitchen, then sit down and eat my meal alone.

Night falls and wind rattles the windows. I worry about my father, but I also think about something Joe said when he was here, that Alzheimer’s patients sometimes need to crash. They need to give up for a while, and stop rising to the occasion.

My questions about coercion remain, especially on the topic of food. Every day Harriet and I press my father to eat. What do you say to some soup for lunch? Here’s a little snack. Would you like a banana? Time for another glass of water. How about some Ensure? We’ve got some great clam chowder. And after dinner the closer, the one that always works: How about some coffee almond fudge ice cream?

Sandy Weymouth has told me how his mother’s attendants, and his own brothers, were always pumping food down his mother’s throat. Not literally, but they urged her to eat whether she was hungry or not. She was ninety-four, then ninety-five years old, she was tired and infirm and didn’t care about eating. But food was gospel and eating her duty. Come on Mom, just one more bite.

What if my father wants to crash for good? What if he’s deeply tired of rising to the occasion, and his way out is to forget about food? I consider this, but I doubt it will be long before I slide another plate in front of him. It’s the habit of care, and the assumption that everyone must eat. Though I question this, I’m tied to the wheel myself.

Dad is completely beat. He still takes a shower in the morning, still comes to the table for breakfast, but then he sits down in his chair, or more likely goes back to bed. He doesn’t read anything, doesn’t say anything, just lies there with his head back and his eyes closed. I go to the library for three hours, and Harriet is here for two of them. She’s bright and enthusiastic and gets him to eat, stretch and talk a little. But by the time I get back his late-afternoon funk has swallowed him. He doesn’t want to drive to the ocean: “Not right now,” he says. He doesn’t want to watch a video: “Not right now.”

Some years ago a friend in Ohio died of colorectal cancer, a long and painful death. Step by step she withdrew into her ordeal, refusing all medication, even analgesics. Near the end she lay in bed, almost unreachable, beside a mutual friend, Kathy Galt. They’d known each other for years, their children were the same age, they had talked and talked—but now, as Kathy spoke, Elizabeth responded with a whisper. Kathy bent closer as faintly, with great difficulty, Elizabeth said, “Words . . . take away.”

I’ve been trying to rouse my father, to entertain him, to entice him out of his blank state—yet perhaps it’s no blank state at all, but a tremendous battle he has taken up in his own quiet way. Perhaps all the offers I make are mere interruptions to that battle. I’m always trying to maneuver him back into the world, but maybe all of it, even talking, takes something away.

After another feast last night, with Dad finishing every morsel of salmon and yams, he made his way to the bathroom, his farts sounding loose enough to be trouble. He closed the door behind him and for twenty minutes I heard nothing. When I asked how he was doing, he announced that he was fine, everything was fine. Another ten minutes brought the same answer. But when I finally opened the door I could see he was confused. He was gripping the handles of the toilet’s safety frame, his pants lay on the floor and his Depends were nowhere in sight.

His underwear was in the toilet bowl, now weighing five pounds. Dad resisted having me clean his bottom, but I cleaned it anyway. This was not, I told him, nearly as messy as the time my mother came to visit me on my farm in Chile, caught a bug and suffered two straight days of delirium and diarrhea. Kind of a ghastly story, but the situation was faintly analogous, and I wanted to let him know I could take care of him, that it wasn’t going to kill me to wipe his ass. I didn’t have to say it was no fun: I think it was harder on him than it was on me.

When I finished and got his clothes back on, Dad thanked me. He still does this, whenever I tighten his belt or bring him his dinner or clip his fingernails. He’s such a polite and decent guy, and his formality is so ingrained that I fear only death will end it—or possibly, extreme dementia.

Like many people, I’m intrigued by disaster: by the rampage of a tornado or tsunami, by a mountain lion that preys on bicyclists, by the electrifying crump of two cars colliding on the street. Or by people come undone in public: the woman screaming in front of the library steps when I lived in Boulder, Colorado, or the guy who unloaded his D9 dozer north of town and flattened the house his wife had taken in their divorce.

The disaster underway in this house is my father’s dementia. Sometimes it crushes me to see his mind giving out, but other times I watch the process with morbid fascination. There’s an element of drama, even glee, in how I report it. The storm is building, the crash is coming, and I want to see how far this will break down my father’s reserve. He’s been through plenty in life and stood firm. He maintained his composure in the face of my mother’s affairs, her departure, and her death ten years later. He stood up to the chaos of his second marriage and a second painful divorce. In this last year he has endured, with never a complaint, Jane’s decline and death. But now dementia is breaking him down. He’s losing control, and there are times I’m not just fascinated by this earthquake of a disease, I almost root for it.

How can I have written that? Only hours later I’m ashamed and take it back, because Alzheimer’s is making him miserable. When I try to get him ready for a walk, he can’t find the sleeves of his coat with his flailing arms. He doesn’t want his usual hat and jerks his head away when I start to put it on, a childish look of dread on his face. He seems to have forgotten the whole process of going outdoors. Watching him cling to his walker with such fear and hesitation, all I want is my constrained and lovely old dad.

After dinner it continues. He lies down on his bed and calls me in. There’s something he wants me to do, but he can’t say what it is. “The third floor,” he says finally. “The people there have to push it up . . . and the people above must pull . . . and . . . and . . . ” He can’t find the words to explain it, and his face contorts in the despair of forgetting. “Oh Jesus,” he says. These are not words I grew up hearing from my father. He is so unhappy.

Looking through books on Dad’s shelves, I find several references to his work and character. Life, in the early forties, brought the war into everyone’s home. There had never been such graphic and immediate coverage of combat, and circulation grew, eventually topping five million, until Life became the country’s most influential and widely read magazine.

Loudon Wainwright, in his book about the magazine, calls my father “a handsome, bright, reserved, efficient fellow,” both “ambitious and proud,” and marked from the start for bigger things. He calls him “cool and sensible.”

In his diary, Life’s first editor, John Shaw Billings, calls my father “a mulish young Yankee” and “a stubborn little New England cuss.”

Tom Prideaux, the entertainment editor, writes that “he never seemed motivated by the desire to show off or disport himself conspicuously. He didn’t have an arrogant bone in his body. Yet there was nothing at all self-effacing about him.”

At most magazines, the managing editor rides lower on the totem pole than the editor. Luce, as editor in chief, ultimately controlled all his magazines, but week to week at Life it was the managing editor who ran the show. In my father’s three years at the helm, Life was in perpetual flux, trying to settle its focus. The war years had been simpler, with the bulk of every issue focused on the worldwide conflagration—and now, occasional arguments flared between Joe Thorndike and Henry Luce. In late 1948, after a “Life Goes to a Party” story about a dissolute ball in Honolulu, with photos of drunken, half-dressed party-goers, Dad received a twelve-page memo from Luce in which he announced that the managing editor “should never settle a dubious question of taste without concurrence of at least one senior colleague.” At that, Dad promptly raised the question of whether he should continue at the magazine. Just as quickly Luce retreated, admitting that he had sent “a hastily-written document.” But their relationship had begun to deteriorate, and only a month later Dad submitted a letter of resignation. “Effective today,” it noted—though he added the escape clause, “unless you have any reasons to the contrary.”

The two of them worked through that crisis as well, but on August 5, 1949, after reading a company memo from Luce that Dad felt undermined his authority, he made it clear he was finished: “I took this job on the understanding that I would have full authority and responsibility under your direction to run the magazine. . . . Last winter I submitted a tentative resignation, for the purpose of finding out where I stood. Lest there be any misunderstanding, this one is final and not subject to further discussion.”

That same afternoon he cleared out his desk and took the train out to Connecticut. He’d had quite a run during his fifteen years with Time-Life, but by then he was ready to start his own projects. Eight months later, along with Oliver Jensen and James Parton, two friends from Life, he started a small publishing company called Picture Press. They did a book on cowboys with photos by Leonard McCombe and a commemorative book for Ford Motor Company on its fiftieth anniversary. Their major projects were the magazines American Heritage (described by the New York Times as “the most ambitious attempt yet made to merge readability with historical scholarship”), which appeared in 1954, and the expensively printed Horizon in 1958. Dad never made his million dollars—not by the age of twenty-five, or even at fifty-five when Heritage sold to McGraw-Hill—but for the rest of his working life he was his own boss and followed his own interests.

Ada Feyerick calls while he’s taking a shower. She worked for him at Horizon and went on to write several books, and now she’s aghast when I tell her he has Alzheimer’s, that he’s deeply forgetful and may have trouble placing her.

“This is terrible,” she says. She can’t get over it. “What a mind he had. Oh, I can’t believe this. He was my mentor, he was a giant in the field—do you know what a giant he was?”

I do know this, a little—but it’s lovely to hear Ada say it. I ask her to call back in forty minutes, and I talk to Dad about her as I help get him dressed. His face brightens at her name, and he says he remembers helping her with her first book. But he also thinks they worked together at Life, decades before he actually knew her. When she calls again I talk to her briefly, then pass the telephone headset to my dad. The headset always disorients him, but it’s our only cordless phone. I settle the earpiece over his ear, and he smiles to hear her voice. Though Ada does most of the talking, he’s friendly and enthusiastic, my old father all the way.

A line jumps out at me from Annie Ernaux’s book about her mother and Alzheimer’s, I Remain in Darkness: “Letting her stay at my place would have meant the end of my life. It was either her or me.”

And from the same book: “Now when I come to see her, I’m still young. I have a love life. In ten or fifteen years’ time, I’ll still be coming to see her but I too shall be old.”

A love life. As long as I stay with my father that seems impossible. Will I even want one, when all this is over? Instead I think of going to see Janir in Colorado, and taking a canoe trip with Barry. I could go to France with my old friend Elisabeth and sit in a café in her native town and write postcards, and relearn some French, and do nothing at all.

Even after his retirement, my father’s life has been filled with writing projects. He has researched and written articles about one of his forebears who was hanged at the Salem witch trials, about Thoreau’s trips to Cape Cod and down the Merrimack and Concord rivers, and about the nineteenth-century Transcendental utopia, Fruitlands. He wrote a futuristic novel, never published, about saving the human species. He outlined plans for a magazine devoted to the outdoors, and wrote a series of personal essays, some a bit pessimistic but none cantankerous, about the twenties, the economy, the natural world, population, and the century to come.

Twenty years ago he began research for his book about the Atlantic coast. He read through a long bibliography of reference works and popular history, and visited a thousand miles of coastline from West Quoddy Head, Maine, to Key West, Florida. In his desk I’ve found audiotapes of his interviews with harbormasters and coast guard officers, blueberry pickers and the head of Maine’s Island Institute. He worked on the book for ten years, and it was published when he was eighty: “An effective combination of eyeball observation, rich history, and sad acknowledgment of how poorly we have used still another national resource,” said Kirkus Reviews.

With that book finished he considered other subjects, expanding his files with clippings and notes about archeological digs, boat trips up the Amazon, the rise of the oceans and the disasters that will follow. But now, in these last few months, all his projects have fallen away. The work he loved is gone, and I think he’s crushed not to have it.

At midday I carry a chair outside and set it on the gravel drive. Dad comes out and sits on it, wrapped in a sleeping bag, wearing his dark glasses and watching the birds at the feeder. I rake the drive and sweep the garage, soaking up a bit of the March sunlight.

Harriet, who will be working at a school camp in the White Mountains for a couple of weeks in April, brings over a friend who might be able to fill in for her, a barrel-chested Irish Bostonian named Jack Lane. He has a ruddy face, a watch cap over his balding head, two bad knees repaired last June, an easy way with words and lots of experience taking care of people. I like him from the start, though I know my father will have to get used to someone who talks as much as Jack does. When he leaves, he takes Dad by the arm and says, “You take care, Buddy.”

That’s how it goes with my father. He does not reach out and touch anyone, but some people take hold of him. It’s hard to know when this is all right with him, and when he’d rather that all of us—including me—kept our hands to ourselves.

I’ve worried about a pair of recent attacks my dad has suffered, small crises that left him short of breath and immobile for thirty minutes at a time. These have baffled both me and Harriet—but ninety minutes after describing them to my father’s general physician, Dad and I were on our way to Cape Cod Hospital for a CT scan and a better look at his lungs.

First some blood work, then they fed some dye into a vein and passed him through the large white donut. We waited. Someone saw something he or she didn’t like on the film, and sent us over to the ER, where after three long hours in the waiting room we were admitted to the inner sanctum. Waves of orderlies and nurses, another registration, Dad in bed in a gown under some covers. Finally a doctor came in. He was moving fast but gave us the direct story. There was a pleural effusion—fluid in the sac surrounding the lungs—and also a small nodule. “I have to tell you, it may be lung cancer. If it is we’ll call for radiation.”

This was followed by more blood tests, antibiotics, an EKG and some prednisone. But to the doctor’s dire announcement I saw little reaction from Dad. With his eyes hooded and his mouth turned down, he didn’t look happy—but after all, by then we’d been in the hospital for six hours, and he hadn’t looked that happy before the doctor came in.

After everyone left the room I talked it over with Dad. I said the words lung cancer, but he did not respond. He barely nodded. He doesn’t want any part of what lies ahead: an appointment with a pulmonologist, then possibly more treatment and more time in the hospital.

His companion, Jane, died of cancer. She’d been treated for it, then told she was cured. At least that’s what she reported to me: “All better,” she told me a couple of years ago. “Clean bill of health.” But when some symptoms returned she refused to go back for more treatment, and my father shares her view of hospitals. It’s the last place he wants to go—and I don’t want to be in the position of forcing him. Could I force him?

Nine hours after leaving the house that morning we pulled back into his drive. I fixed a quick dinner and we ate in silence. After his ice cream I asked Dad if he’d rather spend another day like this one, or a night with the shells flying overhead in a foxhole at Anzio.

“Anzio,” he said.

Twice a day, as he has done for decades, Dad takes three inhalations of a preventive medication for asthma. But recently he’s been having trouble with the inhaler. I’ve upset the routine by trying to get him to breathe the mist in deeply, rather than simply spraying it in his mouth while he locks up his chest.

I sit beside him as we rehearse the steps: breathe out, press the inhaler, breathe in and hold it. This simple operation has become a frightening ordeal. He knows he gets it wrong, and sits beside me with his eyes darting between me and the inhaler. When he does breathe in he can hold it for an amazing length of time, clamping the inhaler between his lips and looking at me as if to ask, Is this right? These are the moments that weaken me, when he looks most helpless and afraid.

His confusions grow worse. He’s forgotten that Al and Ellen are on vacation in New Zealand, and thinks they’ll be coming down from Vermont tomorrow. He thinks it’s early morning and time for his shower, when in fact I’m cooking dinner. He needs to look again at certain boxes of papers, at his checkbook stubs, at a book about the brain written by Jane’s daughter, Susie. He doesn’t read it, but carries it with him everywhere. Yet always he’s the same gentle guy. I’m still waiting for the changes in personality, the anger, the frustration erupting into violence. I want to say, I knew he wouldn’t be like that.

But what will I do if he has lung cancer, and the doctors want to treat it?

I talk to LL about this, Janir’s wife, who’s a doctor in her first year of residency. “Why would you do that?” she asks. “For what? To get him back to where he is now? Radiation is hard on someone his age. It’s hard on anyone. I wouldn’t put him through it.”

I talk to Harriet, who’s even more definitive. “Absolutely not,” she says. “Only palliative measures. Keep him comfortable, treat pneumonia or other problems, but no radiation, no chemo, none of that.”

In forty years of nursing, Harriet has seen it all. I’m glad to have her and LL on my side, because I fear the juggernaut of heroic medical care. It does no good to consult my father about any of this. Though his shortness of breath wears him down, I think he’s lost all ability to weigh the odds, to evaluate the benefits of a hospital stay, to consider that some medical attention might alleviate his symptoms. Given the choice, no matter his condition, he would always want to stay home.

I rarely pass a day now without writing something down about my father. I came here hoping to look after him as long as I could hold out—and now I think I’ll write about him for the rest of his life. He’s ninety-one, he has Alzheimer’s and asthma and atrial fibrillation, and now perhaps cancer, and I can’t imagine he will live for another year. But my stay, this journal, and the end of his life now seem inextricable, each with some influence over the other. Don’t die, I sometimes think, because I’m not finished writing about you.

The pulmonologist, Lawrence Pliss, soothes both of us. He slows down, he explains everything, he has a sense of humor, he covers all the options. It might be cancer, he says, but he doesn’t think so. Dad hasn’t smoked in sixty years, and then it was only for a year at the office. More likely, Pliss suggests, it’s congestive heart failure. He asks us to go over to the hospital and have an x-ray taken. After that he’ll either tap the lung from behind and withdraw some of the fluid or wait to see if Lasix will take care of it. Lasix is a diuretic that helps drain the body of the excess fluid that builds up with CHF.

Congestive heart failure: a condition marked by weakness, edema, and shortness of breath, caused by the inability of the heart to maintain adequate blood circulation in the peripheral tissues and lungs.

The hospital is just down the street from Pliss’s office, and Radiology takes us right away. I sit on a bench as a pretty young nurse walks my father down the corridor to the x-ray machine, giving me a glimpse of how he must appear to others: a bent old man with rundown shoulders and unruly white hair, shuffling along with six-inch steps. My father, of course, is polite to this woman, and she is friendly to him. But I doubt that she can see the young man in him. When watching other old people, I can’t do it myself. What would lead me to imagine that this old woman loved to dance the rumba, or that old man once ran the high hurdles, or that some stiff old couple once trekked through Nepal together? The older they are—and no one in the hospital looks older than my father—the harder it is to think of them as having once been young and supple and audacious.

I want to tell the young nurse about the summer day in 1955 when Marilyn Monroe showed up at our house to go waterskiing.

That was a big year for Marilyn. The Seven Year Itch, her twenty-fourth movie, had just been released, along with the iconic photo of her skirt blowing up above a sidewalk vent. What legs on that dazzling blonde, and what a smile.

My father had long been friends with Milton Greene, who was both photographer and friend to Marilyn, as well as an occasional business partner. Marilyn was spending the weekend in Connecticut with Milton and his wife, and mentioned to them that she wanted to try out the new sport of waterskiing. So Milton called my dad. We lived on Long Island Sound and had a little boat, though the motor was barely strong enough to pull a skinny twelve-year-old out of the water. I was twelve and, disastrously, had gone off with a friend for the day. But Dad knew someone with a bigger boat. Charlie Goit leapt at the chance, and Milton, Marilyn and a small retinue drove over to our place.

I wish I knew, or Dad could remember, what she wore and what she said, and every little detail. All I really know is that someone had to get into the chest-deep water with Marilyn and help her with her skis and keep her from tipping over until the line drew taut. And that was my father.

Up she surged, then crashed. Charlie circled around, Dad held Marilyn, and off she went again. On the third try she skied for a hundred yards, and Charlie got to haul her into the boat. But when I came home that evening the detail I heard from friends, neighbors and family, over and over, was how Charlie had to drive while my father stood in the water with his arms around Marilyn Monroe. I think everyone liked the irony of that, because Charlie was kind of lascivious, and my father more of a gentleman.

Fifty years later, walking down a hospital corridor with a pretty girl, my father has become a very old man. But he has some stories.

And tonight, over dinner, I ask Dad what he remembers of that summer day in 1955. Though he can’t come up with many details, his version of the waterskiing seems pretty close to my own. He isn’t sure about the bathing suit, but yes, most likely a two-piece. I admit to leading him some. And yes, he had his arms around her. “Around her waist,” he says.

After that I can’t help teasing him. “So someone had to get in the water and help out?”

“That’s right.”

“And that person wound up being you.”

“Well, Charlie had to run the boat.”

“And before you knew it, your arms were around her waist.”

Deadpan, with only the faintest twitch of his eyebrows, “No alternative, really.”

Dad isn’t happy with Jack Lane. He doesn’t remember his name, but calls him the guy who talks too much. Though it’s true that Jack can gab, he’s sensitive to Dad’s position. “This is your father’s sanctuary,” he says, “and I’m the intruder here.”

I keep thinking Dad will come around, as he did with Harriet. I hope he will, because she’s about to leave for two weeks at her camp, and without Jack I’ll have no help. A Friendly Visitor program from the Council on Aging has fallen through, as well as assorted respite care from Elder Services. After an interview and extensive paperwork, I might get a miniature grant for an eight-hour break planned weeks in advance. But what I really want is what I have now: two or three hours in the library every day, and two outings of tennis a week at the club I’ve joined. That ensures my sanity, and we have the money to pay for it. The problem is that except for Harriet, Dad doesn’t want anyone to come over.

Am I coddling my father? My friend Elisabeth writes from Montreal:

I think you should absolutely leave your dad sometimes for a few days in that home you visited. You would be sure trained people would take care of him, he wouldn’t die for a stay of a few days and he would probably care more about you when you take him back home. He would probably be angry at first but inside he would understand that you need a bit of a life and that he is lucky to have you. Don’t feel guilty about this.

But she also understands how my father would hate to live in one of those homes that look, as she says, “like a waiting room for death.”

I think if I put my father in a place like that he’d be dead in three weeks, and I don’t want that. I don’t think I’ll want it until he does. Though many of his friends have now died, he never talks about their deaths or says a word about his own. He wants to live, and while I sometimes feel trapped in his house, and in his life, I still want to give him what he wants.

From bedroom to bathroom and back again, that’s his only trajectory. “I’m a pissing machine,” he told Harriet yesterday.

If a lifetime of strictures on his speech can fall away, I wonder if in the end he’ll come around to welcome being rubbed, or even held. Annie Ernaux writes, “Being alive is being caressed, being touched.” Not so for my father. But perhaps he must fall back further toward childhood, to his early childhood, to whenever his parents last held him.

So many elemental facts of his life are lost forever. When did his mother last hold him?

These days, in fact, he is touched more and more. Harriet takes off his socks and kneels in front of him to rub lotion into his ankles. When I come into the room she looks up at me like a child who’s getting away with something. The podiatrist buffs Dad’s nails, businesslike but with a feminine touch. Nurses weigh him, take his pulse and blood pressure, hold his arm as he walks. I dress him. He doesn’t like his shirt cuffs buttoned, so every time I put on his sweater his sleeves get drawn up around his soft biceps, and I have to reach up under his sweater sleeves, over his hairless forearms, and pull his shirtsleeves down. Somehow this feels more intimate to me than anything else I do.

The smallness of our days. Breakfasts and dinners at which we don’t say a word. Nights when he’s in bed by eight.

At three in the morning I wake, not suddenly but in stages. I must have had a dream but can’t remember it. Outside, the lawn glares white with snow under a setting moon. Will this winter never end? But that’s not it. Something large and overwhelming is wrong. Slowly it uncoils. My father is going to die, and I’m going to be alone.

He has been here always, every day of my life. He’s falling apart but he’s still my father, and once he goes I’m going to be left in a room in the middle of the night, in a house with a groaning furnace, and there’ll be no meaning to any of it. So much will vanish when he’s not in this world. It’s four in the morning but I don’t go back to sleep. I don’t read or write, I just lie there missing him.

Easter morning, sunny and cool. Many are off in church today, but in my father’s house we are keeping our own counsel. Dad is asleep, though he was awake earlier. Since no one is coming over today and there’s nowhere we have to go, I’ve decided to let him choose when to get up. Every other morning I appear downstairs with a cheery greeting and an offer to heat up the bathroom. But all offers are coercive, and for once I’m not making any.

It’s ten o’clock but I’m letting him sleep. Most days that’s what he does anyway: he eats breakfast and goes back to bed, to sleep or simply lie there. I’ve also decided to try Sandy’s regime, and bring Dad food only when he asks for it.

Noon. In Florida Terri Schiavo is living without food or water. In Rome the pontiff comes to his window but is too ill to speak. On Cape Cod I have corralled my father on one of his passages to the bathroom and given him his medications. His heart rate and blood coagulant level will stay under control, and the Lasix will continue to flush his system. For now the house is still, and Dad goes on sleeping.

I debate every step of this. Will he never ask for something to eat or drink? He’s supposed to take plenty of fluids, but it’s always been a struggle. If a patient is unconscious you just dump the liquid down the tube, but each day I must convince my fully conscious and resistant father to drink a glass of juice or water, then another and another.

My poor dad, up and down, back and forth to the bathroom as the Lasix wrings him dry. I’ve set out some snacks on the dining room table, so each time he passes he might see them. No interest so far. I haven’t said anything about taking a shower or changing his clothes. It’s two in the afternoon. The sun pours in through the newly cleaned windows, but Dad doesn’t seem to notice the outdoors. He walks to the bathroom and returns to his room. He gets onto his bed, pulls the quilt up to his chin and lies there, still as a carving on a sarcophagus. He sleeps.

I’m going crazy, just watching him. I’ve tied myself to his day, to discovering what he wants. The whole debate about Terri Schiavo is over what she would have wanted for herself, and here on this formless Sunday it’s clear that my father wants to lie in bed and not be bothered by anyone. He seems to have given up—but maybe that’s what he has wanted all along. And if he wants to give up, doesn’t he have the right to?

Three o’clock. How long will I let him go without drinking water? I’ve put two full glasses by his bed, but he hasn’t touched them. I pace around the living room, I sit on the couch, I don’t step outside into the beautiful afternoon. I sink with my father.

Five-thirty. The sun is going down, he looks exhausted and I can’t stand it anymore. I’ll make him drink something, then fix a dinner and set it before him. All offers are coercive, and so be it. But the question I’ve asked all day remains unanswered. Should I return to my jaunty self tomorrow morning and make him take a shower, make him change his clothes, invite him to sit down to his breakfast and morning medications, urge him to walk to the mailbox, insist on driving him to the ocean, hound him about drinking more fluids? At what point should I just let him do what he chose to do today: lie in bed without talking or moving.

I remember what the neuropsychologist said about taking Dad to the senior center: Don’t ask him about it, just take him. I resist that, because Dad hates going over there. Yet today, on the one day I give him completely free rein, he winds up with no shower, no breakfast, no lunch, no time outdoors and no conversation. He’s passed what seems to me a lost and unhappy day, stretched out on his bed.

And I have to ask: how much did I do this because I wanted a break myself, a day without responsibilities?

In the evenings, after I tuck Dad in, I’ve taken to sitting on his bed as he worries. His brow tightens, his voice quavers and his language drifts into scraps. I can never help him figure out what has gone wrong, or what he must do, but perhaps my presence makes it easier for him to give up the battle. Sometimes he simply drifts off. Other times he stops to signal his defeat. He sighs, he lets his eyes close and says in resignation, “Well, thank you.”

Last night, sitting in the living room, I heard an odd mumbling from his room. I stepped to the door and found him pointing toward the foot of the bed. He couldn’t speak. Instead he gurgled and groaned, with a look of consternation and a skinny finger jiggling in the air. I tried to figure out what he wanted, but couldn’t. Was it the lamp? His hand wagged back and forth: no no no. Was it the dictionary? No, not that. His finger quivered and pointed toward—nothing, there was nothing there. I touched the curtain and he came out with a single clear sentence, “No, that’s not it.” But the next moment he was back to groaning, and no more words would come. His face drew tight with the effort.

This goddamn disease. There is always some new disaster and humiliation.

I moved my hands over the quilt. I touched the top of the wainscoting, and at that he spoke again: “That has to go.”

“I don’t think we can move this, Dad. It’s part of the wall. We have to keep the walls.”

He was calming down. He seemed to have recovered. He said “Good. Good. I just needed you to touch it.”

Sometimes I wonder what I’m doing here—and then I imagine my father in a nursing home. Who would sit on his bed at night as he struggled with memory and order? How often would someone take him outside to sit in the sun? When would he have a dinner of ocean scallops and fresh asparagus? My dad would be the least demanding resident, and the last to complain. He’d just take what they gave him. I imagine visiting him in such a place, and how unhappy I’d be to see it.

I’m in the midst of giving Dad an emergency bronchial spray for one of his rare asthma attacks, when Jane’s daughter Susie calls on the phone. It’s not a good time to talk, but she promises to call back, and after dinner Dad waits by the phone. Normally his interest in the phone is nil, but now he’s going to wait beside it until it rings. It does and he picks it up. I don’t know who it is, but Dad is abrupt. “I can’t talk now,” he says, and hangs up. It rings again, and he picks up the receiver. It’s a call from Athens—I have ads in the paper, trying to find tenants for next year—and I get off the line as fast as I can. Ten minutes later, Susie.

What a smile she brings to his face. I don’t think I’ve ever seen him beam like this, not with his children or grandchildren or anyone else. It’s stunning, really. Months have passed since he last mentioned Jane’s name, but every minute he’s on the phone to her daughter his face is lit up.

After her call he’s completely energized. He can’t tell me what Susie talked about, but he sits at the table going through a New Yorker, an Atlantic Monthly, through the notebook in which Harriet records the details of her visits. Then he looks up and says, “Where’s my money?”

“It’s in your accounts.”

“No, my money. What about the money that was spread out on the floor?”

“You mean dollar bills?”

“It was all over the place.”

“Dad, I’ve never seen any dollar bills lying around. I would have picked them up.”

“Well I want to see them.”

He’s still confused and upset about his joint checking account with Al, and I explain once again how that works.

“Is it my money, or is it Alan’s?”

“It’s yours, but he can spend some of it for you.”

“Why don’t the checks come to me anymore? I haven’t seen them.”

I explain about direct deposits. He wants to see the bank statement, and I have the latest one in a folder, ready to send to Al. But the statement now comes with a photocopy of the cancelled checks, and there he’ll see the checks Al has been writing to me for staying here and looking after him. I’d rather he didn’t see these, but he wants the statement so I hand it over.

He takes the statement and his checkbook into his room and sits down on the bed, and for forty minutes I hear the shuffle of pages. Finally he calls me in. “I can’t make anything of this.”

I reassure him. I tell him that after selling his house he has plenty of money. Most of it’s in his mutual funds account, and he can spend it if he wants to, on whatever he chooses.

He listens. He considers. “What about you? You should be getting paid.”

“I am getting paid.” And finally I explain to him my arrangement with Al and Joe. “The fact is, you are paying me, a thousand dollars a week. It comes from your account.”

His hand flutters up, then back to his checkbook. “You should be getting paid more.”

This makes me wonder why I’ve been so secretive about it all along. “I’m getting paid plenty,” I tell him, “and I’m really glad you’ve got the money for it.”

I could say more about this. I could explain that I never completely escape the feeling that I should be doing this out of pure love. I know, by how seldom I mention it to other people, that there’s something shameful about being paid for a job that so many others, in their own families, do for free. It doesn’t matter that Dad, now that he’s sold his house, has plenty of cash. Indeed, it could be said that he sold his house—something he didn’t really want to do—so he could pay me to come live here. Money gets tricky fast with families and the elderly. While I know I’m doing a job no one else could do, it’s awkward to put a price tag on it.

My doubts lift fast when the money arrives. I might be feeling desperate and shut in, worried about how long my life will put be on hold—but promptly, every two weeks, Al sends me a check for two thousand dollars, plus everything I’ve spent on food and household expenses. Save for a couple of years when I had some big movie advances, this is more than I’ve ever made in my life. I love these checks. I practically caress them before sending them off to my bank. I’m building up a wad to pay down my several mortgages, and I keep track of my checking account online, watching it as it grows. Just as Lois promised, money can take care of many discontents.

“Can I stay in my house?” my father asks.

“You’ll always be able to stay in your house, Dad. You have three sons who love you, and we’re going to make sure you don’t have to go into a nursing home.”

“I have that right, to stay in this house.”

“You have that right, and we’re going to defend it.” I don’t add any caveats.