Four

ONE LATE SUMMER WEEKEND, Susie comes down from Edinburgh with a suitcase of my grandparents’ papers. From my memories of sorting though their house, I don’t expect there to be a treasure trove of Hannah material here, but I am still disappointed at how little there seems to be: a folder of early poems and drawings, reports from her primary school, some photographs.

Of the usual teenage paraphernalia of diaries, letters, schoolbooks, photographs like those Shirley showed me, there is no sign. Though Hannah spent five years at boarding school, there are none of the letters she must have written to her parents. Unless Hannah got rid of her teenage things when she left home, they must have been discarded either by my grandparents or my father. Suicide not only ends a life, it changes how that life is remembered. The happy, hopeful times are refracted through the end, invalidated by the act of the death.

Most of the papers are my grandfather’s unpublished typescripts. He published half a dozen books, as well as hundreds of articles and essays, but these are various attempts at a memoir. To my grandfather, though, memoir meant recollections of his times, the people he met, rather than his own personal life, and there again seems to be disappointingly little about Hannah.

It is a relief, though, after the turbulence of the past weeks, to hear my grandfather’s familiar wry voice in my head. He was the wisest man, at least in the ways of the broader world, I have known, and I loved talking to him, listening to him. And as I read, I find, tucked away in his portraits of interesting people and times, occasional mentions of his family. From these fragments, and others in his published books, along with clues Susie continues to send, and conversations with her, I begin to piece together Hannah’s early life.

SHE WAS BORN, I know, in Palestine, but I learn now how my grandparents had come to be there. They had met and married in London, where my grandfather had lived since his wandering Zionist parents had brought him there at the age of thirteen, and my grandmother had come from the small town in South Africa where she had grown up to ‘go to the theatre and see art galleries’. My grandfather was working as a floorwalker, or trainee manager, at Marks and Spencer, and writing a novel. When his novel was published without much notice, he threw in his job and they sailed to South Africa to visit my grandmother’s family, and it was on the way back that they stopped in Palestine.

They had meant to stay only a few weeks, to see my grandmother’s brother and sister, and my grandfather’s father, who had settled there. But my grandfather was still working out what to do with his life, and through his father’s Zionist connections he got a job at the Jewish Federation of Labour. My grandmother also found work at a school run by a disciple of Freud in Tel Aviv, and it was in this modern city rising out of the sands, on 19 August 1936, that Hannah was born.

Two early influences on Hannah’s life emerge from my grandfather’s writings. One is a memory of standing at the glass looking at his newborn daughter, and his sister-in-law beside him saying, ‘Das Kind ist klug’ — that child is clever. It was something Hannah had to live up to all her life: that she was clever, precocious, that things were expected of her.

More immediate was the world into which she was born. My grandfather was reading newspaper reports from the Spanish Civil War when a nurse came to tell him that he had a daughter: ‘I was only too well aware that in Hannah I had acquired a new and special responsibility and there was world war looming ahead.’ Hannah was always known as Hannah, but the name on her birth certificate was Ann — the English, non-Jewish, version of the name.

There is nothing more in my grandfather’s writings about Hannah’s first year and a half, but among the material Susie brought is a small photograph album that gives a sense of her early life in Tel Aviv. Here are my grandparents holding Hannah proudly in a flat furnished with the sparse austerity of settler life. Here is her nanny pushing her in a wicker pram along dirt roads past low stone apartment buildings. And here she is, a year or so later, riding a tricycle, toddling into the sea, with the broad smile I know from later photographs, looking at different times remarkably like both my daughters.

An ‘enchanting sprite’, my grandfather wrote, in his one written recollection of her in Palestine:

Small, slender, agile, she was enormously precocious. At eighteen months, when we were passing a kindergarten, Hannah ran inside, insisted on joining in the game and there she remained and held her own. Now she was twenty months, she was running in an imagined game through our apartment, she spoke in clear sentences and then started out on what she unfortunately already knew was her parlour trick: reciting from her Babar books, which she knew by heart, and turning the pages at the right word, as if reading.

By now, my grandfather had given up his job to write a book about the prospects of Palestine. He had grown up in a Zionist household, and he writes of falling ‘under the passions of that insecure little land’. Returning from a tour of kibbutzim, with their utopian dreams, he ‘felt suddenly and uneasily aware of the barrenness, the hollowness, of Western middle-class life’. But it is interesting that his Zionism didn’t blind him to the aspirations of the Palestinian Arabs, and the prescient thesis of his book, with its equally prescient title, No Ease in Zion, was to advocate a combined Jewish–Arab state.

In his later years, he followed Israel’s progress closely, still arguing for more pro-Arab policies, increasingly saddened by how those utopian dreams had turned out, but it is only now that I realise how close he and my grandmother came to throwing in their lot with Zionism and staying in Palestine. How differently Hannah’s life would have turned out, though I wouldn’t be here to write about it. But as it was, more powerful than my grandfather’s attraction to Palestine was his desire to be a writer. When the news broke that Hitler had annexed Austria in March 1938, the ‘action for a writer’, he decided, was in Europe, and he flew back to London, my grandmother and Hannah following more slowly by sea.

IN LONDON, my grandparents rented a little house in the Vale of Health, on the edge of Hampstead Heath. Hannah, now nearly two, ‘briefly produced a sleep disturbance and crying fits’. Removed from her home and her nanny, this was hardly surprising, but my grandmother’s work in Tel Aviv had turned her into a confirmed Freudian, and hearing that the Freuds themselves were living only a short walk away, she wrote to Anna Freud for help.

Anna Freud ‘wrote back with exquisite politeness that she could not yet take cases’, but suggested another refugee psychoanalyst, Marianne Kris, who agreed to see Hannah. My grandfather recalled with a mixture of amusement and fascination how ‘the eminent Dr Kris at once gained Hannah’s attention, gave her a Daddy doll, a Mummy doll, a Hannah doll and a nanny doll, and asked her to play a game’. Separation anxiety was duly diagnosed, and after being prescribed some extra cosseting, Hannah was soon running about with her ‘usual zest’.

My grandmother enrolled her at a nursery school in Highgate, and in the mornings, waiting for the school bus to pick her up, her excitement ‘was so great she could not contain herself, hopping madly from leg to leg’. She soon acquired the ‘precise, high pitched enunciation of English upper-middle class children’.

This new life was not to last long, though. To my surprise, I learn that in the summer of 1939, whether with the intention of escaping the looming war or of taking Hannah to see her parents before war made this impossible, my grandmother and Hannah sailed for South Africa. Equally surprising, my grandfather set off on travels around Europe, taking in, among other places, Berlin, where he wandered ‘among the “No Jews Desired” notices like a spook’. He had spent his early years in Strasbourg and Zurich, but he was born in Cologne, and he wrote how grateful he was for his British passport.

Whatever her intentions in travelling to South Africa, my grandmother must have decided to outrun the war back to Europe, for by the winter of 1939 the family was together again in a guest house on the Ridge in Hastings. Perhaps they had chosen that spot so my grandfather could gaze across the sea to France, ‘the waters silvery in the moonlight along the blacked coast’. In September 1939, he had ‘stood for a day in a senseless queue of volunteers outside the War Office’; but in his efforts to sign up, his German birth counted against him, and instead he began writing a book about racial equality, influenced by what he had seen both in Germany and South Africa, to which he had taken a dislike from the moment his ship ‘arrived in Cape Town and I saw the black African porters in their cast-offs standing on the dock below like accusing dark shadows’.

In the mornings, he or my grandmother took Hannah on the trolley bus to her new school. When it snowed, she ‘played boisterously in the deep snow with two friendly Alsatian dogs’. In May, the Germans attacked the Maginot Line, and three weeks later the family watched the flotilla of boats sail for Dunkirk.

By summer they had moved again — into a farmhouse near Twyford, in Berkshire, with my grandfather’s publisher, Fred Warburg, and his wife. Warburg introduced my grandfather to George Orwell, who was a frequent visitor, and the three of them came up with the idea of the Searchlight series of books on war aims — my grandfather’s book on race, The Malady and the Vision, would be one; Orwell’s The Lion and the Unicorn, another.

Hannah, now nearly four, and the only child in the house, was ‘the little queen of the place’. My grandfather wrote of ‘Fred Warburg, that haughty publisher, lying on his back in the grass and holding her high in the air’ and ‘Orwell, stretched out on the grass, reading Hauff’s fairy tales to her’.

She was already on her fourth educational establishment, a few miles away in Sonning, to which she travelled on her own by Green Line coach. Returning one afternoon, my grandfather recalled, ‘she asked for the stop too late, and the coach overshot the stop where I was waiting by three-quarters of a mile. Hurrying in that direction, I came upon the tiny figure running towards me along the Great West Road with a tear-stained face, nearer, nearer, and into my arms.’

The arrangement at Scarlett’s Farm was not to last either, though, and by the following summer my grandparents and Hannah had moved again, this time more permanently, to the cottage outside Amersham.

My grandfather was in England for another couple of years, but he was working for the BBC, and later the Foreign Office, in London, and there is no mention of life in Amersham in any of his writings from that period. In 1943, he was finally taken into the army as a psychological warfare officer and he sailed for Algiers. His years in the army were good times for him, and his memoirs record his travels through north Africa and Italy, where he interrogated prisoners at Monte Cassino. But from the story of Hannah’s life his voice now fades, at least for a few years.

ON A COLD late autumn day, I drive out to Amersham. Susie has told me that the cottage was on London Road and was called Evescot, but the name must have been changed, for the only reference I can find online to Evescot, London Road, is a notice from 1942 of my grandfather’s anglicising of the spelling of his surname from the original Feiwel to Fyvel, in his efforts to get into the army.

Susie told me it was one of a row of a dozen-or-so cottages, and with her directions I find the cottages without too much difficulty. I had always understood that Hannah lived on the edge of town, but it is a mile outside Amersham here, cars speeding past, and fields climbing hills on both sides of the road.

Susie was four when they moved away, and the only clues she could give me is that Evescot was towards the southern end of the row; that ‘Clarkie’, or Mrs Clark, the housekeeper Hannah locked in the chicken shed, lived next door; and that there was a cherry tree outside the front door.

I walk along the row, examining the cottages. A couple have cherry trees out front, and I pick one of these and ring the bell on the door behind it. A middle-aged man eventually comes to the door. He has been here for twenty years, he says, but none of the cottages was ever called Evescot, as far as he knows, and he doesn’t remember any Clarks living here. No one else has been here as long as he has. I explain my interest, peer past him hopefully. This could be the cottage where my mother lived. But he does not take the hint, does not invite me in.

I drive up to the local library, but there is no information there. I call Sonia, but she can’t help either. Susie says she would recognise the cottage if she saw it, and suggests we drive out together next time she is in London, though she is not due down for a few weeks and I am impatient. It is hard to explain why it is so important to me, but it is: this is the cottage where Hannah grew up, where she lived in the stories that until recently were all I knew of her childhood.

I think about the Clarks. Susie says they stayed on at London Road after the Fyvels left, and though she doesn’t know where they went, it is not unlikely that they remained in the area. Clarkie would surely be dead by now, but what about her son, Roger, Hannah’s friend in my grandmother’s stories?

Clark is a common name, and I am not sure it wasn’t Clarke or even Clerk, but searching online I discover a Roger Clark from Amersham, of about the right age, who belongs to a vintage-car club, and through this I get his phone number.

When I call, Roger seems almost as delighted to hear from me as I am to have found him. Evescot was the third cottage from the left, he says. The Clarks’s was the end cottage. They lived there until 1961. Hannah came with my grandmother to visit when he was about fourteen or fifteen, he remembers, but he stayed in his room and refused to come downstairs.

HIS WIFE IS about to have an operation, but he would be happy to see me after that. Less impatient now that I have found him, I suggest a day when Susie will be in London, and a couple of weeks later, Susie and I drive out to Amersham.

On the way, Susie reminds me of my grandmother’s stories, some of which I have forgotten. The incident with the chicken shed was apparently part of a broader campaign Hannah waged against Clarkie. On another occasion, she helped Roger escape when Clarkie locked him in his room by instructing him to tie sheets together and climb out of his window. She also orchestrated the local children to hide in the brambles when Clarkie went blackberrying and to jump out at her. These stories carry me so readily back to the images in my childhood mind that I am almost surprised when we knock on Roger’s door and it is answered by a smiling grey-haired man and not the boy of my imagination.

In his sitting room, Roger shows us a picture of himself as exactly the gap-toothed boy I pictured. Though when we tell him about my grandmother’s stories, he corrects us. His mother may have helped my grandmother out with eggs — it was her chicken shed — but she wasn’t anyone’s housekeeper. Nor was she ever cruel to him.

He and Hannah, he tells us, were part of a gang of children living in the cottages who went around stealing apples and walnuts from people’s gardens, picking mushrooms, hunting squirrels with homemade catapults. The men were mostly gone to war, and the fields and woods and roads were empty. In those days, you could wait for an hour for a car to come along London Road.

There was a rubbish dump a little further along, and they would search through it for anything they might be able to use — old toys, bicycle parts. They found a bathtub once, and dragged it down to the river, and plugged up the hole and used it as a boat. At night they would sit on the dump, smoking cigarettes.

All this is new to me — Hannah the tomboy, as Roger describes her, running wild with her countryside gang. Though I wonder how much these are Roger’s stories, how much Hannah was actually present in them, whether she wouldn’t often have been at Chesham Bois or gymkhanas with Sonia and Tasha.

He had seen Hannah coming up the drive, Roger says, the time she and my grandmother came to visit when he was fourteen or fifteen, and had shouted down to his mother to say he wasn’t there. Why? I ask. ‘Because she looked so beautiful and sophisticated’ and he was ‘a teenage boy with acne’. He stayed in his room until they left. That glimpse out of the window was the last time he saw her.

AFTERWARDS SUSIE and I stop at the cottages. We know which one was Evescot now, but it refuses to look any different from the others. She asks if I want to ring the bell, and I shake my head. I don’t need to see inside any more; it is enough to have met Roger, heard his memories.

On the way home, Susie tells me more about those times. I knew my grandmother as she was in her older years, fastidious about dirt on her carpets in her Primrose Hill house, at war with the cats that defecated in her garden, but Susie says she enjoyed her years in the country. She didn’t have a car, but she could cycle or take the bus to get around. Her cousin, Lila, often stayed with her and ‘taught her to drink’: they would go to the pub in the evening and ‘drink gin, brandy, rum, whatever they could get’. Together, Susie says, the two women ‘discovered that life could be pleasant without men’.

Hannah, too, seems to have thrived in a female household. When Lila’s dog had to be taken to the vet to be put down, the three of them took her together, and Hannah had the idea of singing hymns to cheer them all up, and soon the whole of the upper deck of the Green Line bus was singing along.

Among my grandparents’ papers are a handful of letters my grandmother sent to my grandfather during the war. In one, dated October 1943, she wrote of a visit from an army friend. Hannah, then seven, was ‘very sweet and anxious to hear all about her Daddy. She came down in her night-gown and a lovely red velvet cloak. She looked very charming and behaved in a delightful way.’

Most of the references to Hannah are about her achievements: reading Oliver Twist at seven, writing four poems in an evening — though one mention, while complimentary, hints at a more challenging girl. She is ‘on top of her form. She is so helpful and so very easy. I can’t remember when I last had a scene.’

The poems in the folder Susie brought are all from this period. They include several that were published in a children’s periodical and one broadcast on the BBC, presumably the competition of my grandmother’s story. They are precocious for a seven- or eight-year-old. ‘Like water from the ocean great,’ reads one, ‘Women weep about the gate. /The canary up on the wall /Has watched us sobbing in the hall.’ But they are all imitative like this, don’t say much about her other than that she was clever, good at fulfilling adult expectations.

Her precocity did lead to her being pushed ahead a year in school. In her first school report from St Mary’s School in Gerrards Cross, she was just five while the average age of the class was six and a half. ‘Hannah has settled in and made good progress this term,’ her early reports read. ‘Hannah has a very good memory, quite a wide vocabulary.’ But comments about her intelligence and abilities were soon being tempered by concerns about her attitude. ‘Hannah’s enthusiasm is delightful but she needs to learn not to be assertive and to realise that other people are equally important.’ ‘Hannah is inclined to demand too much attention.’ ‘She is still too noisy, and must learn both to speak and to move more quietly.’

These reports seem to me more revealing of Hannah’s personality than her poems, if not always perhaps in the way that the teachers intended. I don’t doubt that she was assertive, boisterous, noisy, but I wonder if there would have been so much concern about these characteristics if she had been a boy.

Among the papers Susie brought are also some photographs from the Amersham days. One is a school photograph in which Hannah stands at the end of a row, half the size of the other children, her hair in pigtails, a proud smile on her face.

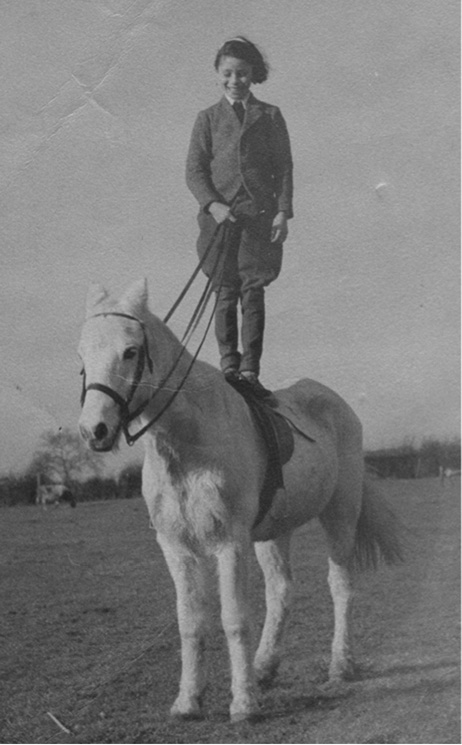

Several are of Hannah riding in a pair of oversized jodhpurs. In one, she is galloping, bent forward over the horse’s mane, a fierce expression on her face. In another, she is standing on the saddle of the horse.

Most moving to me are a couple of contact sheets taken several years apart, presumably at a portrait studio. Each consists of forty-eight shots, and looking from one shot to the next is almost like watching a clip of film.

In the first, she is five or six, wearing a coat with a hood. She is clearly being asked to smile, but she keeps forgetting and starts looking around, and then is told to smile again and does so, more and less genuinely.

In the second, she is perhaps nine or ten. She is wearing a polka-dot blouse and a little white bow in her hair. She is a bit more toothy and gawky, more self-conscious. In some of the shots she grins broadly, but in others she purses her mouth as an older girl might do, or is caught looking sideways at the camera, and it seems to me that I see on her face a sense of expectation, a readiness, impatience, for the adventure of life to come.